полная версия

полная версияHistory of Julius Caesar Vol. 2 of 2

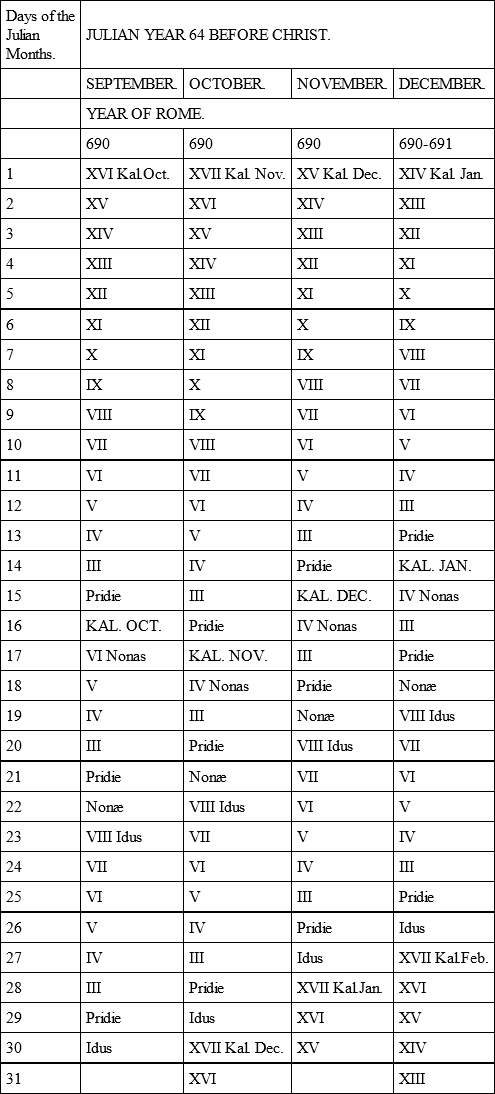

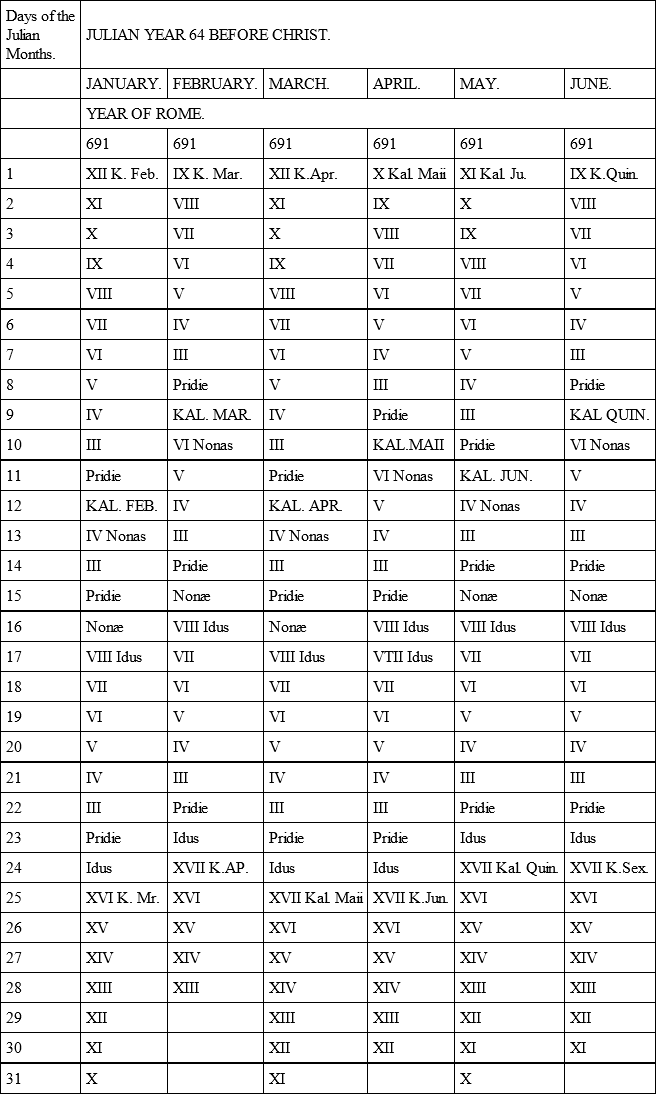

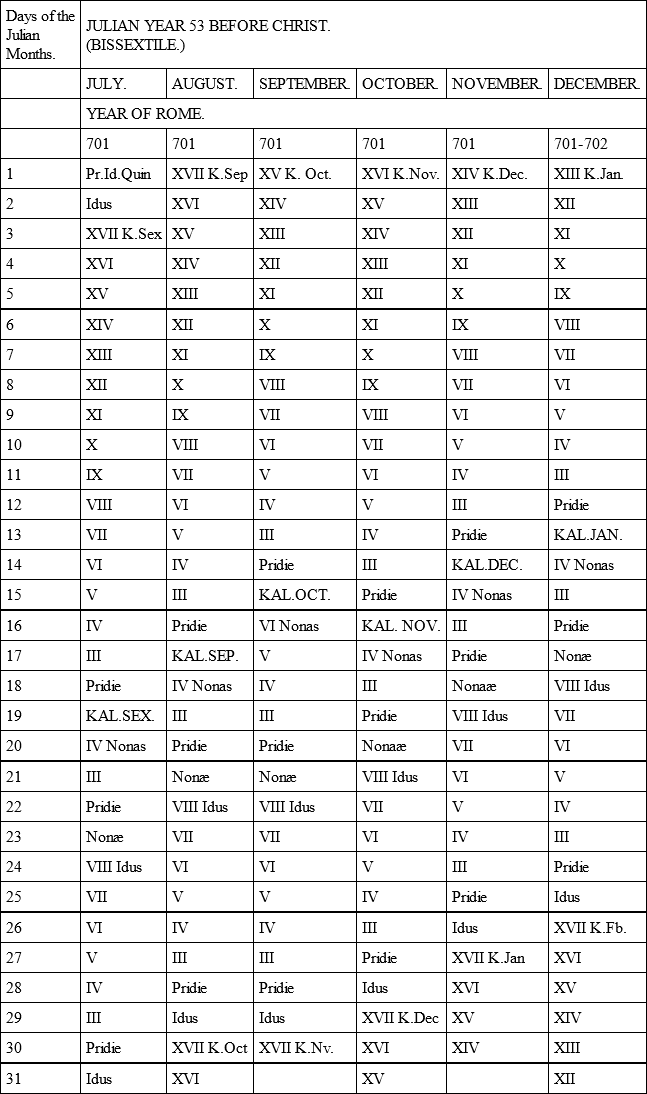

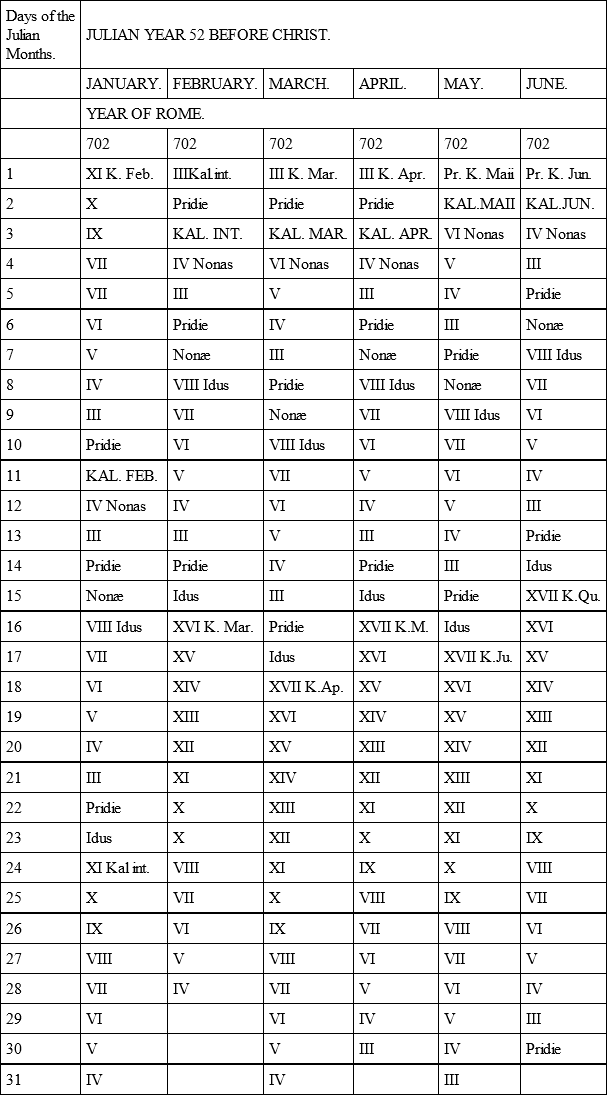

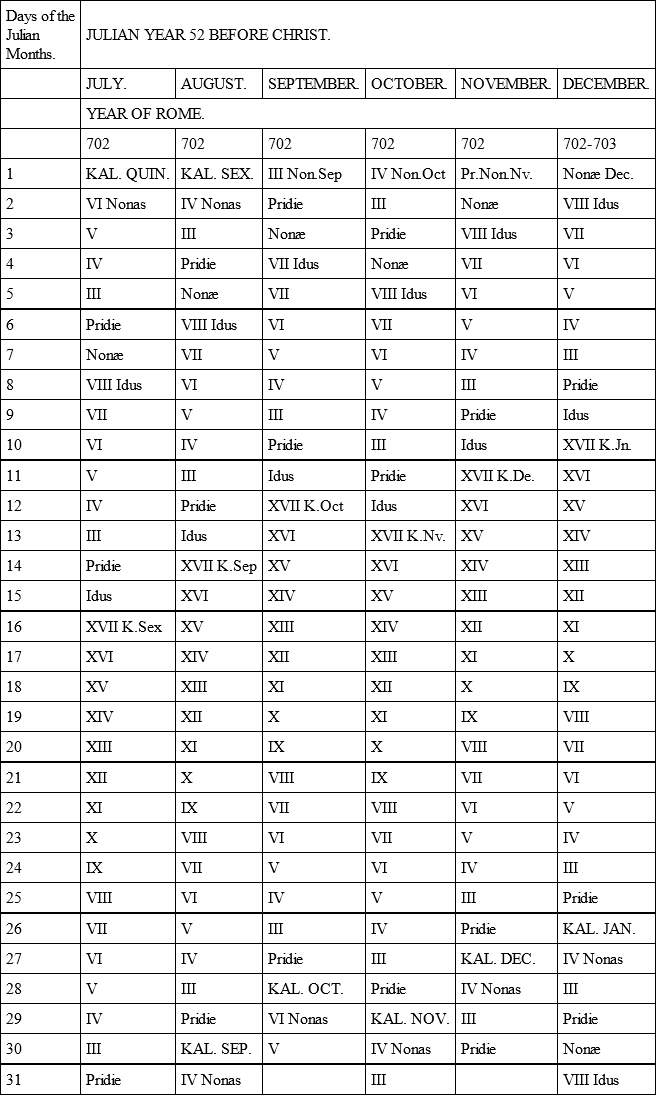

In the year 702, on the 13th of the Calends of February (that is, on the 30th of December, 53 B.C.), Clodius is slain by Milo. (Cicero, Orat. pro Milone, 10.) Pompey is created consul for the third time on the 5th of the Calends of March, in the intercalary month. (Asconius.)

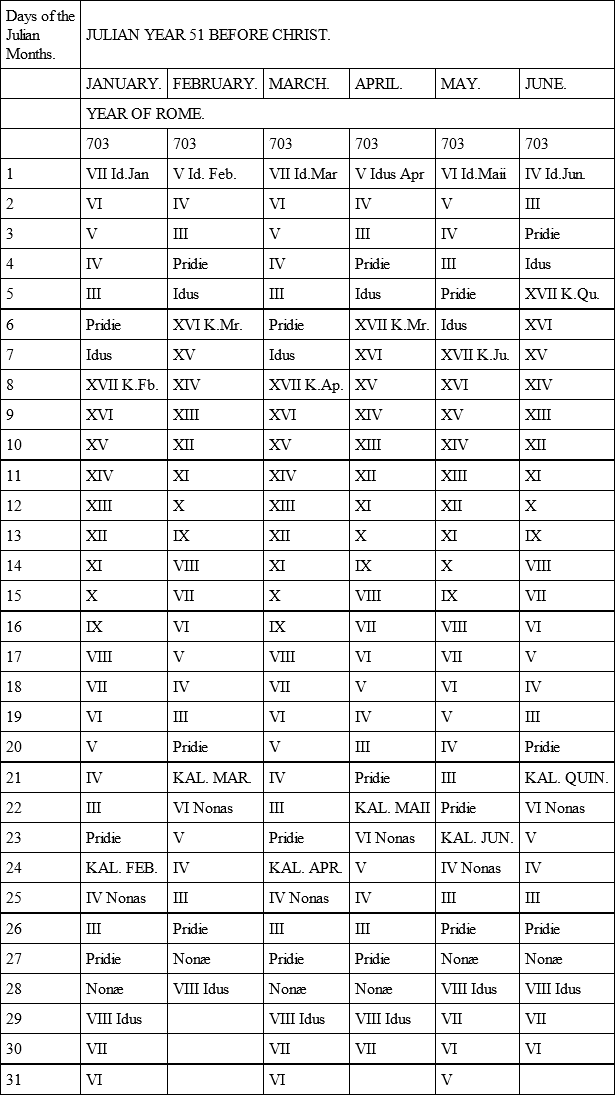

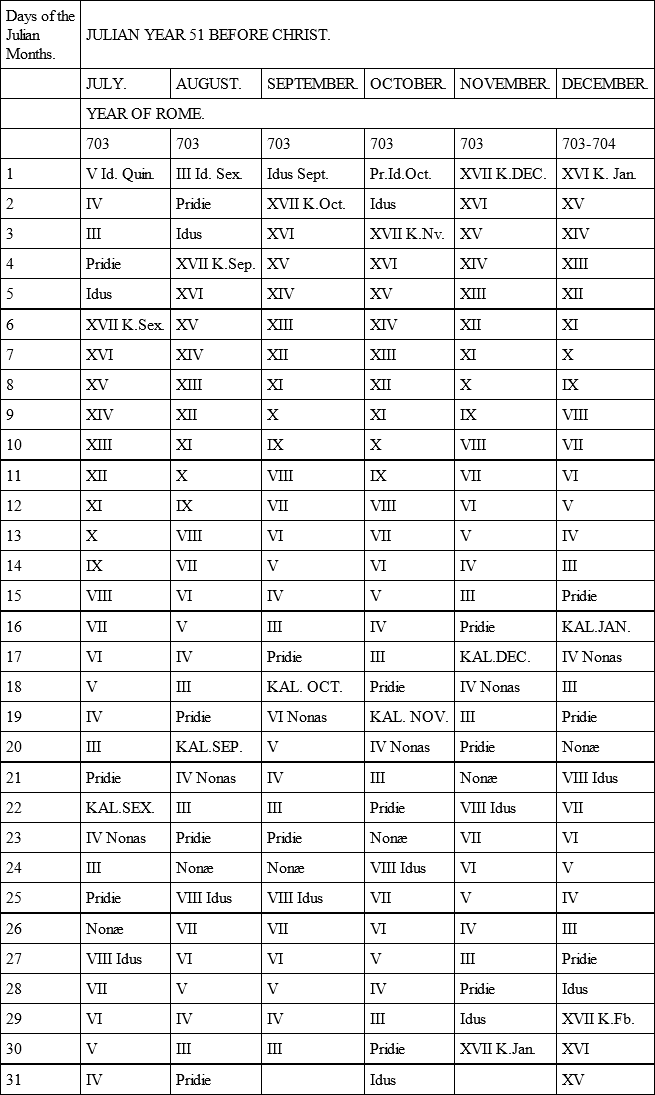

In the year 703, Cicero writes to Atticus (V. 13): “I have arrived at Ephesus on the 11th of the Calends of Sextilis (12th of July, 51 B.C.), 560 days after the battle of Bovillæ;” an exact computation, if we count the day of the murder of Clodius, and reckon 23 days for the intercalation of 702.934

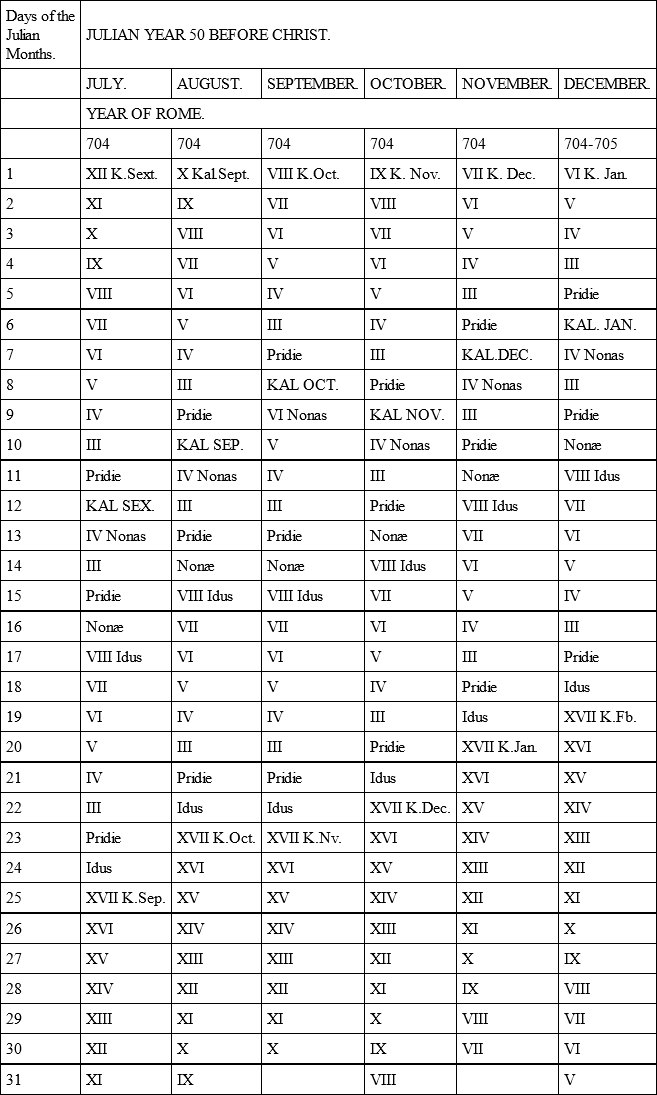

In the year 704 the intercalation is omitted. Cæsar’s partisans demanded it in vain. (Dio Cassius, XL. 61, 62.)

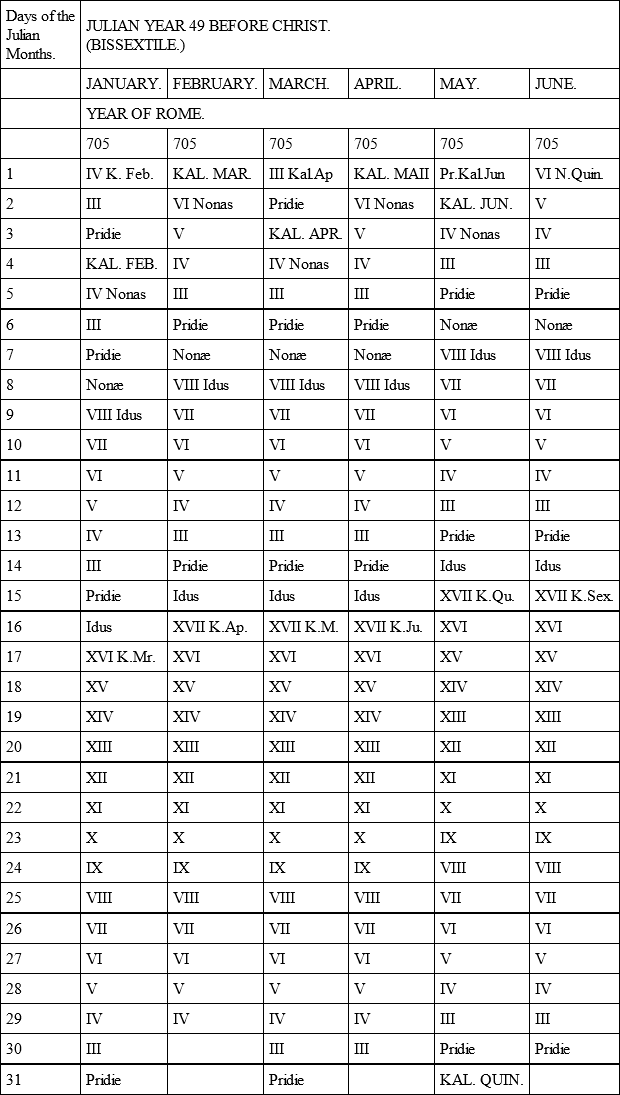

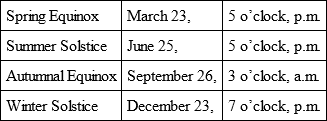

In 705, Cicero, who hesitates in joining Pompey, writes to Atticus: “a.d. xvii Kal. Junii: Nunc quidem æquinoctium nos moratur, quod valde perturbatum erat.” It was the 16th of April; the equinox was passed 21 days before, and the atmospheric disturbances might still last. Or was it anything else than an excuse on the part of Cicero?

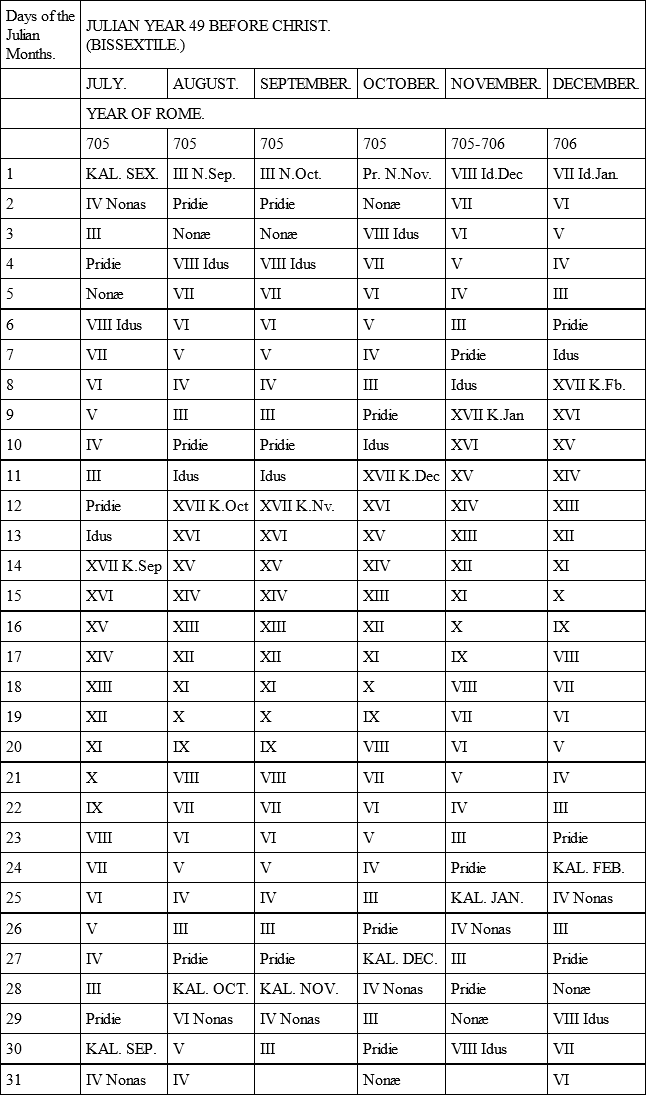

Cæsar embarks at Brundusium on the eve of the Nones of January, 706. (De Bello Civili, III. 6.) It is the 28th of November, 49 B.C. “Gravis autumnus in Apulio circumque Brundusium … omnem exercitum valetudine tentaverat.” (De Bello Civili, III. 2, 6.) – “Bibulus gravissima hieme in navibus excubabat.” (De Bello Civili, III. 8.) – “Jamque hiems appropinquabat.” (De Bello Civili, III. 9.)

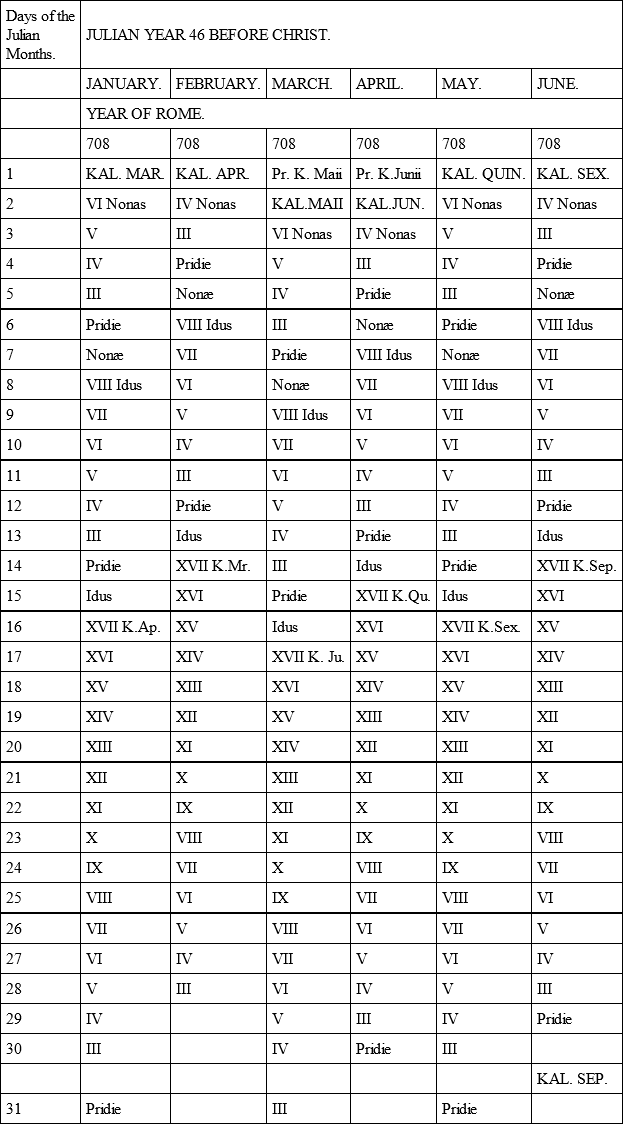

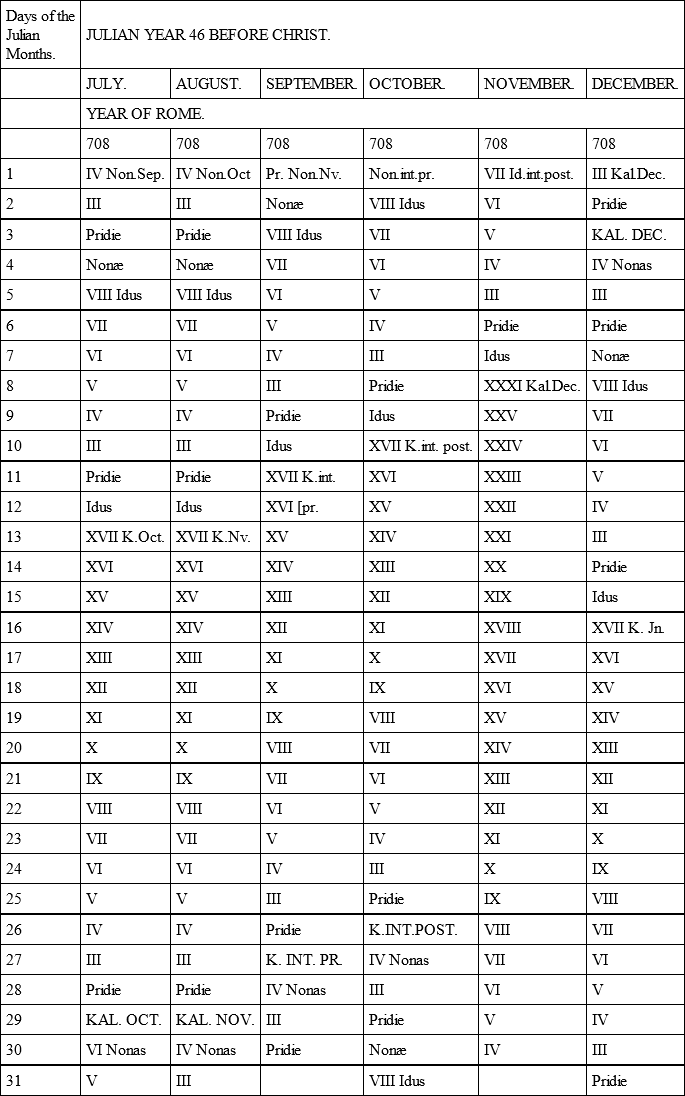

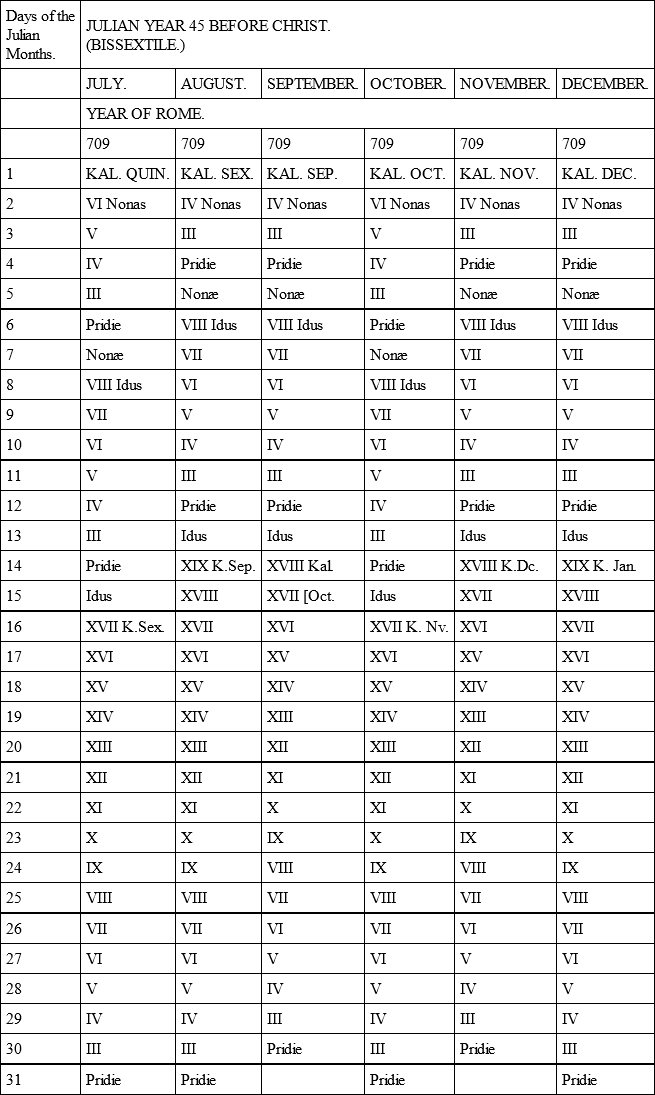

After his arrival at Rome towards the end of the year 707, Cæsar started again for the African war. It was only on his return towards the middle of the year 708, that he could devote himself to the re-organisation of the Republic and the reform of the calendar. According to Dio Cassius (XLIII. 26), “as the days of the year did not concord well together, Cæsar introduced the present manner of reckoning, by intercalating 67 days necessary to restore the concordance. Some authors have pretended that he intercalated more; but this is the truth.”935

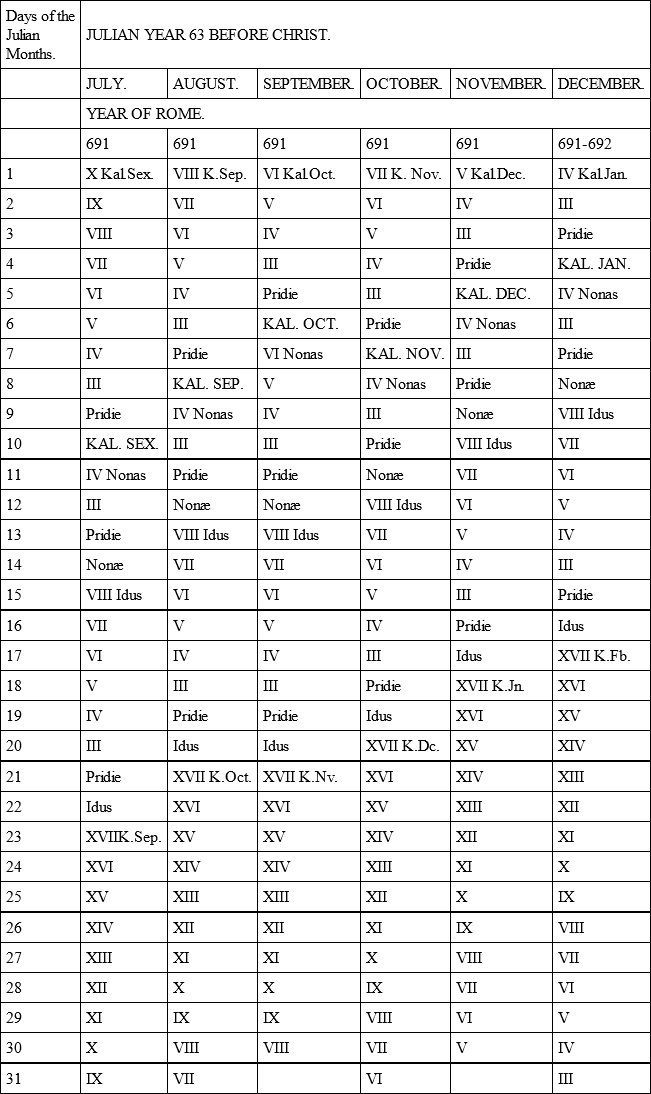

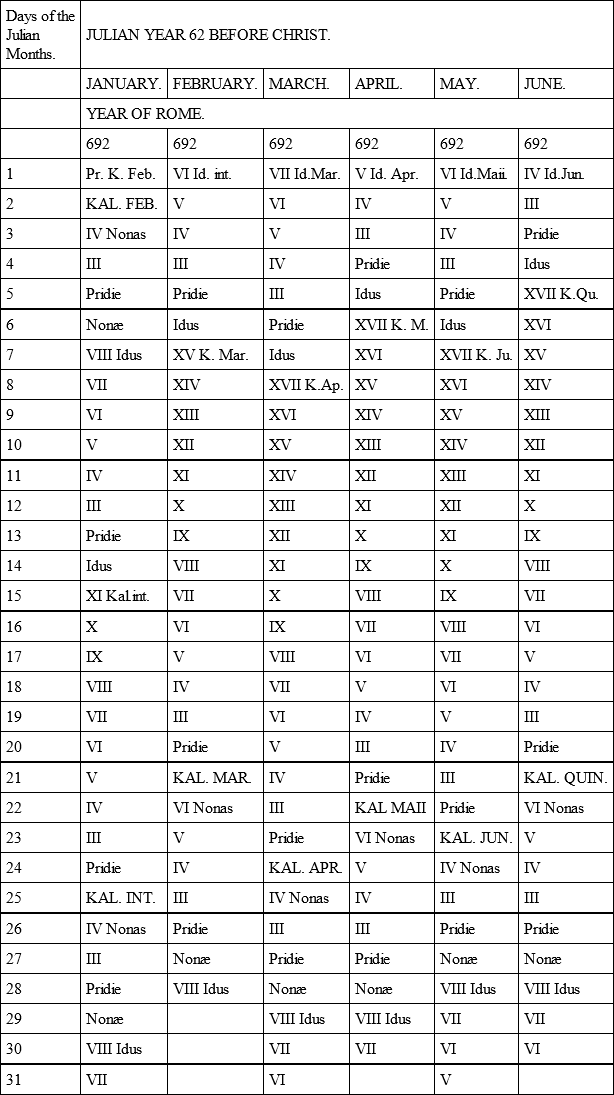

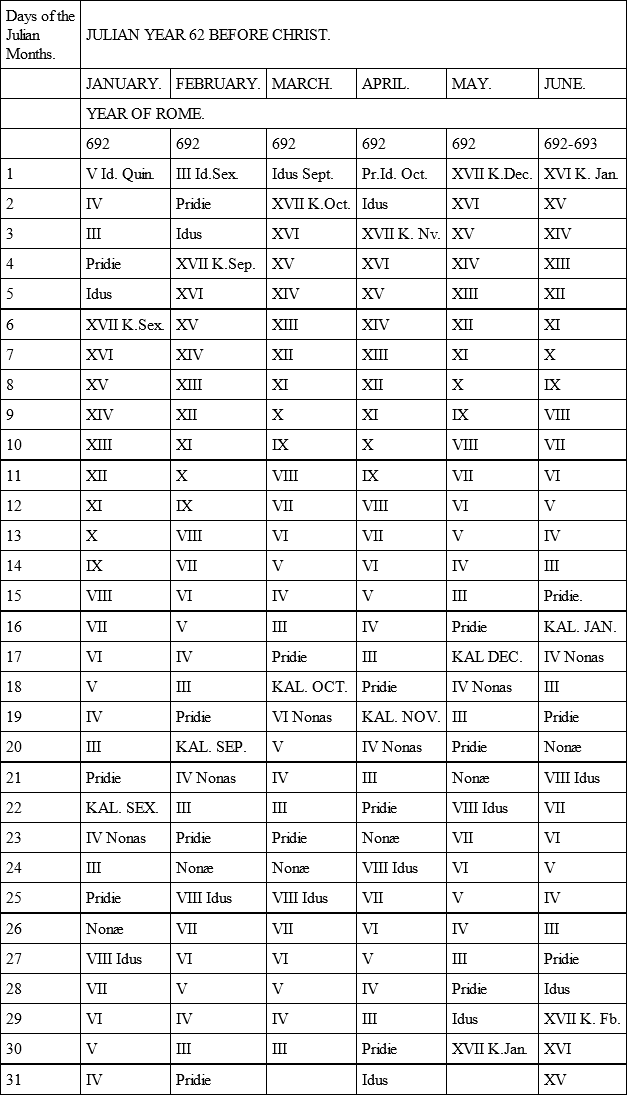

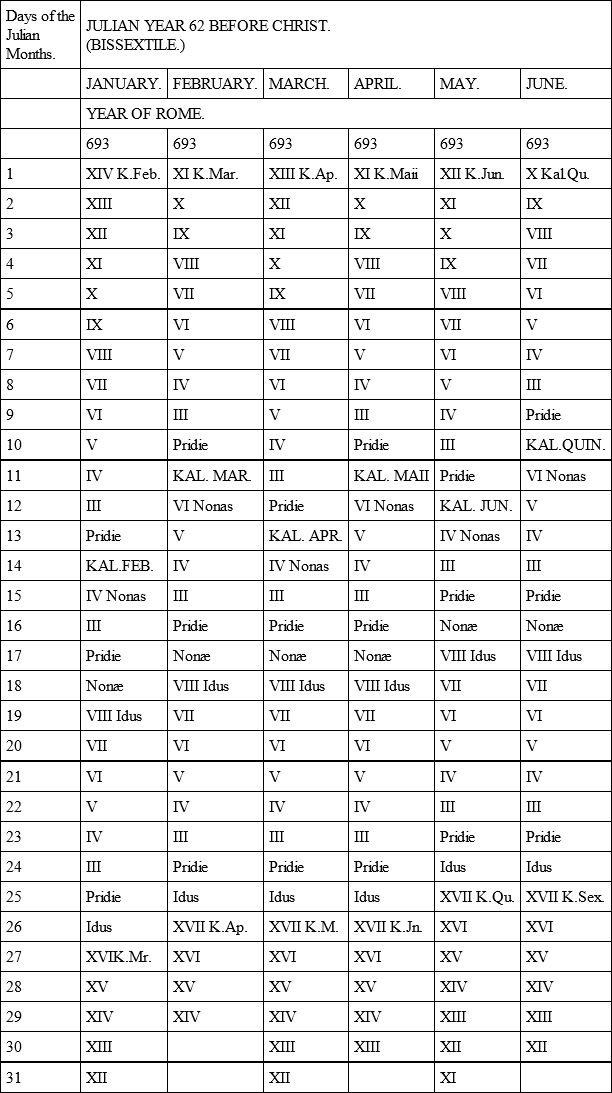

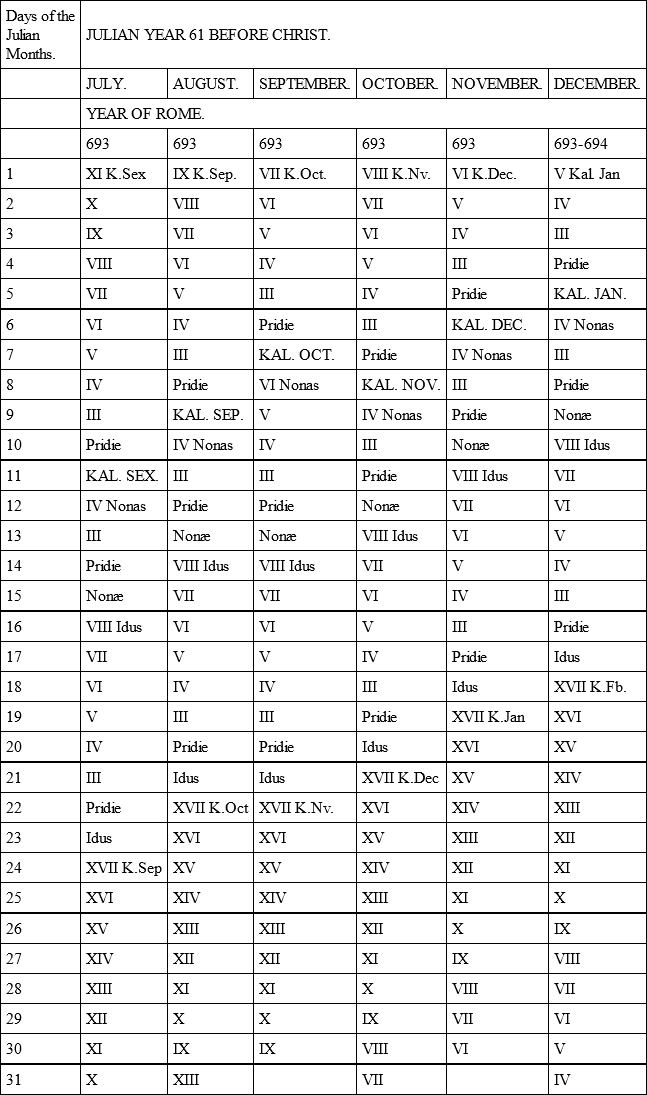

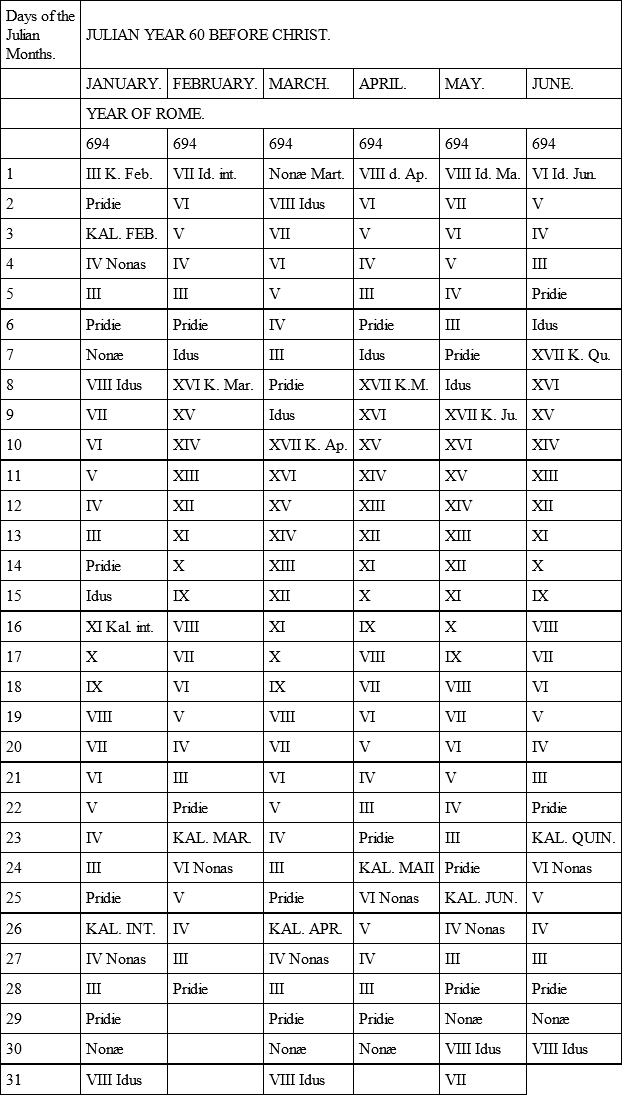

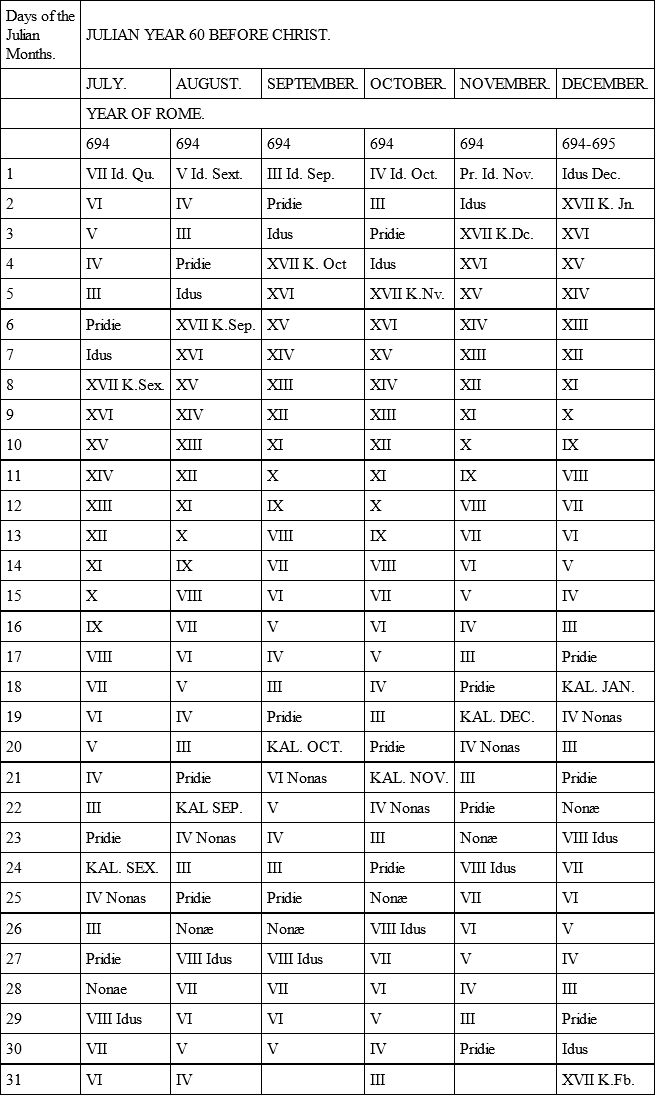

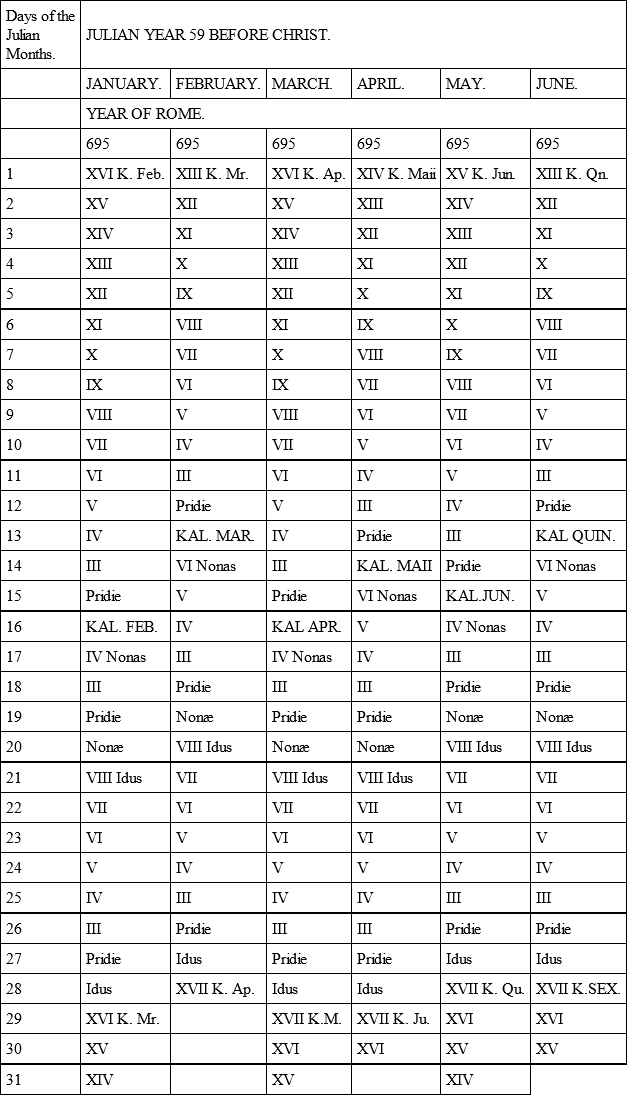

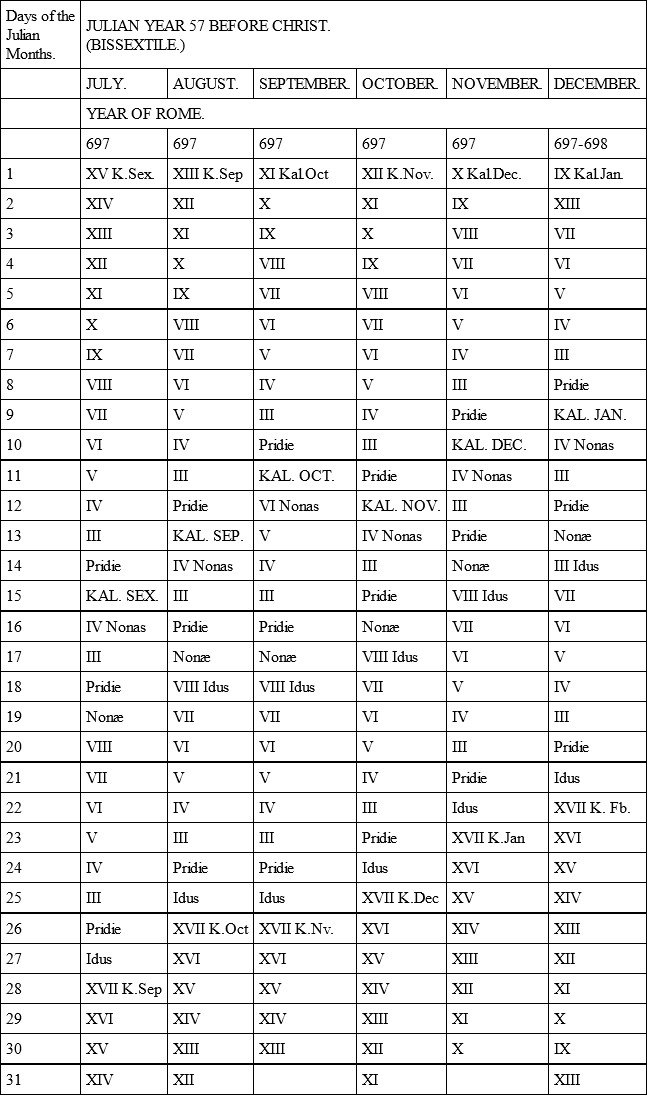

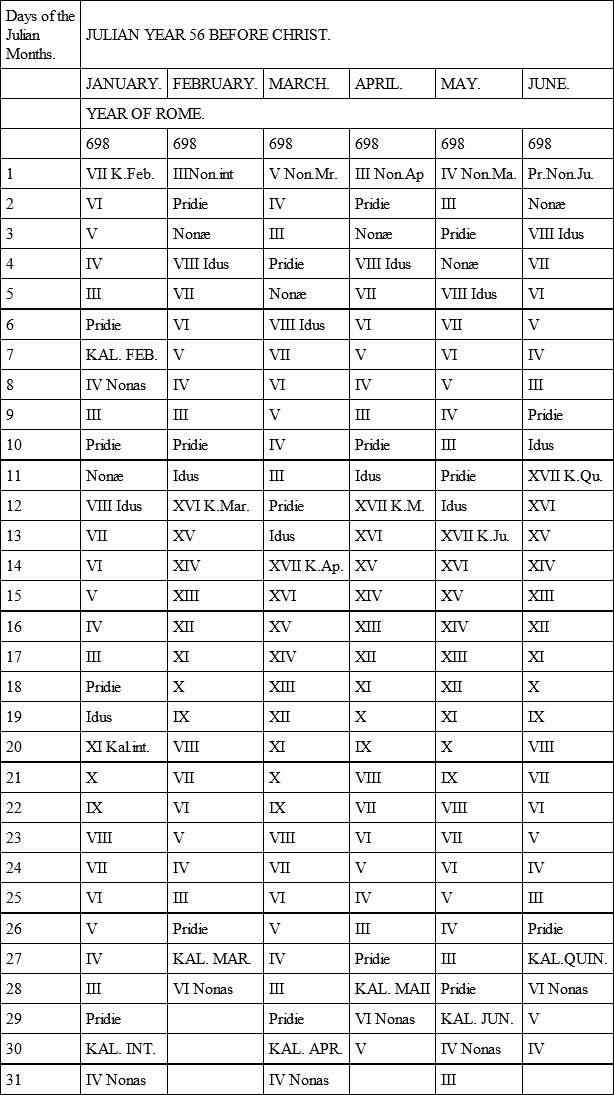

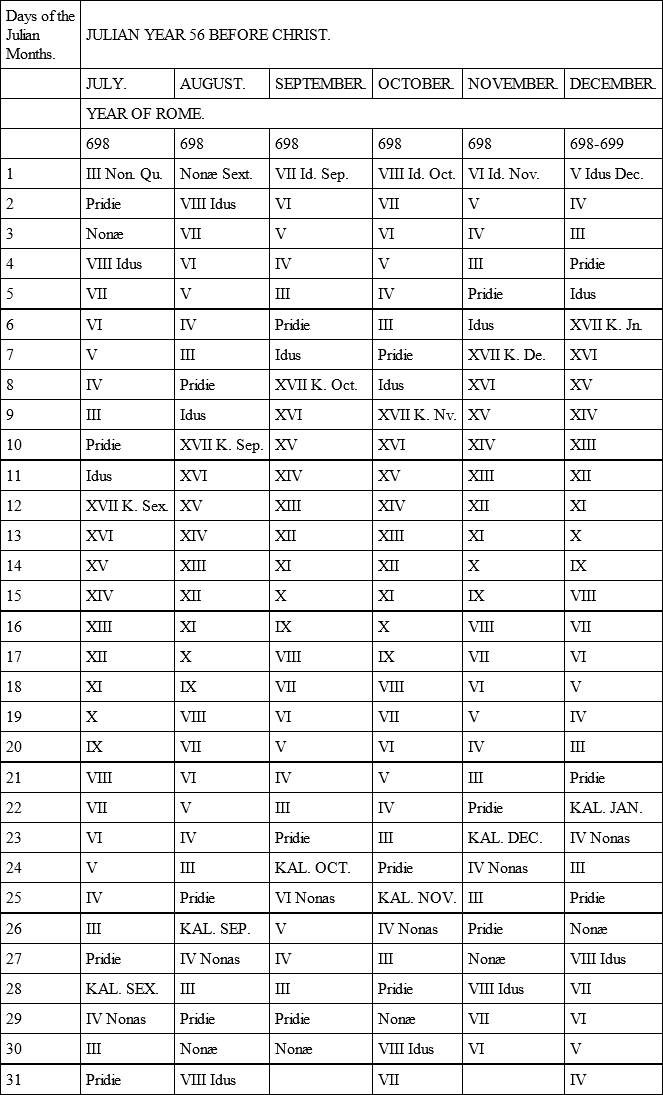

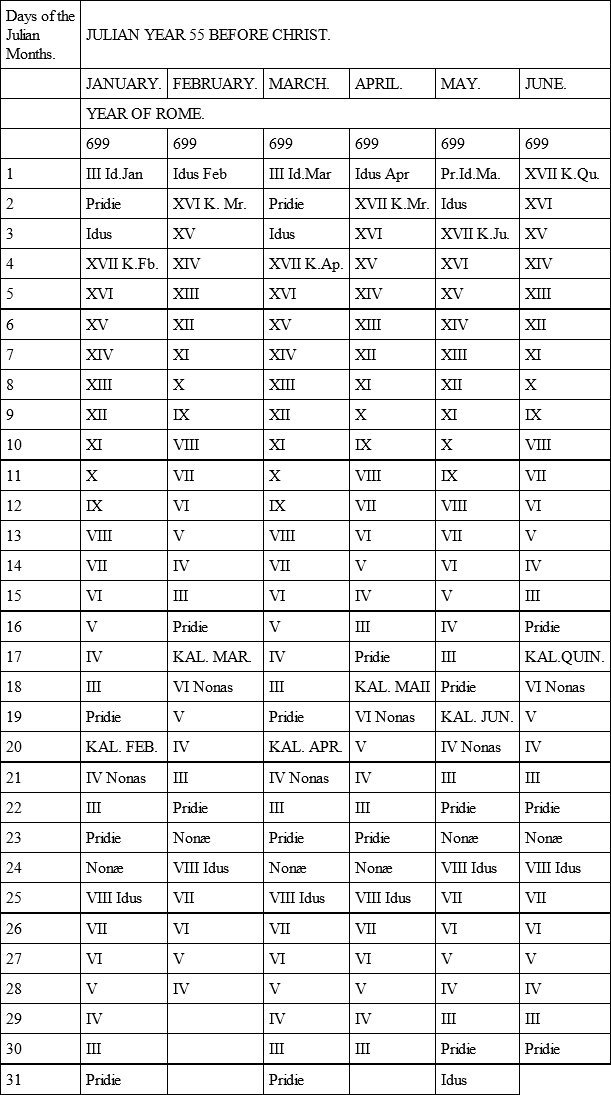

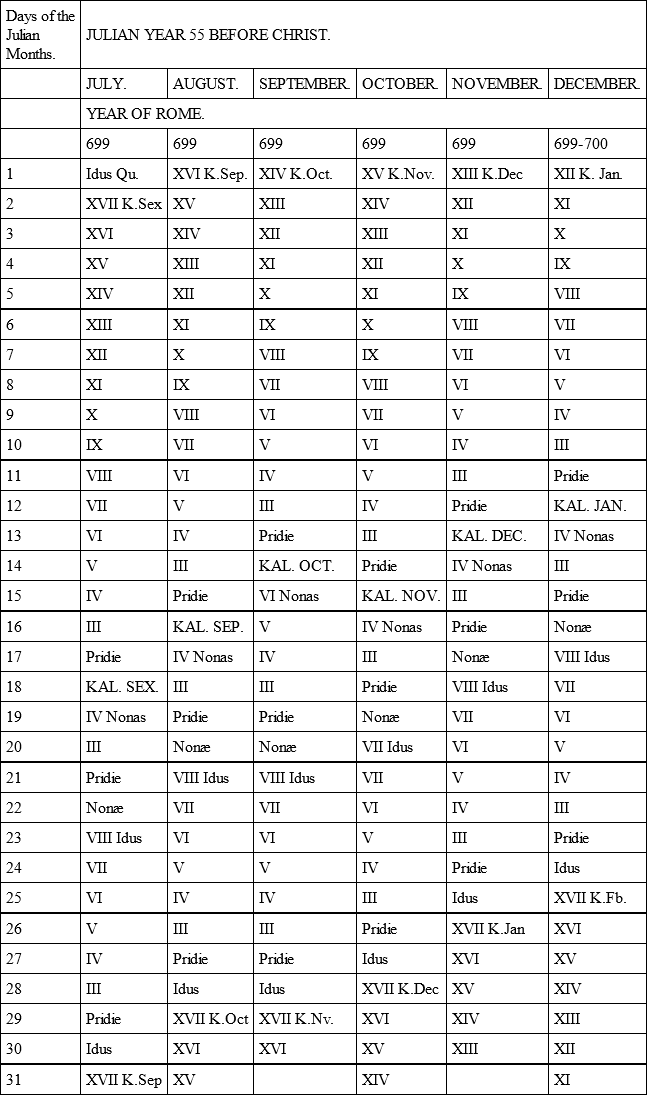

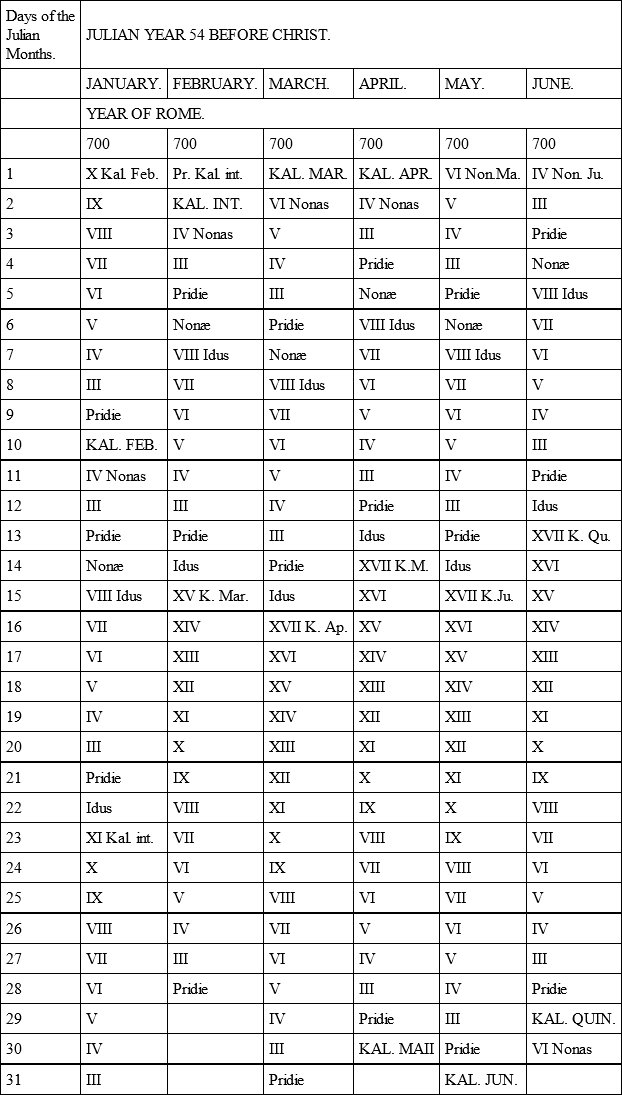

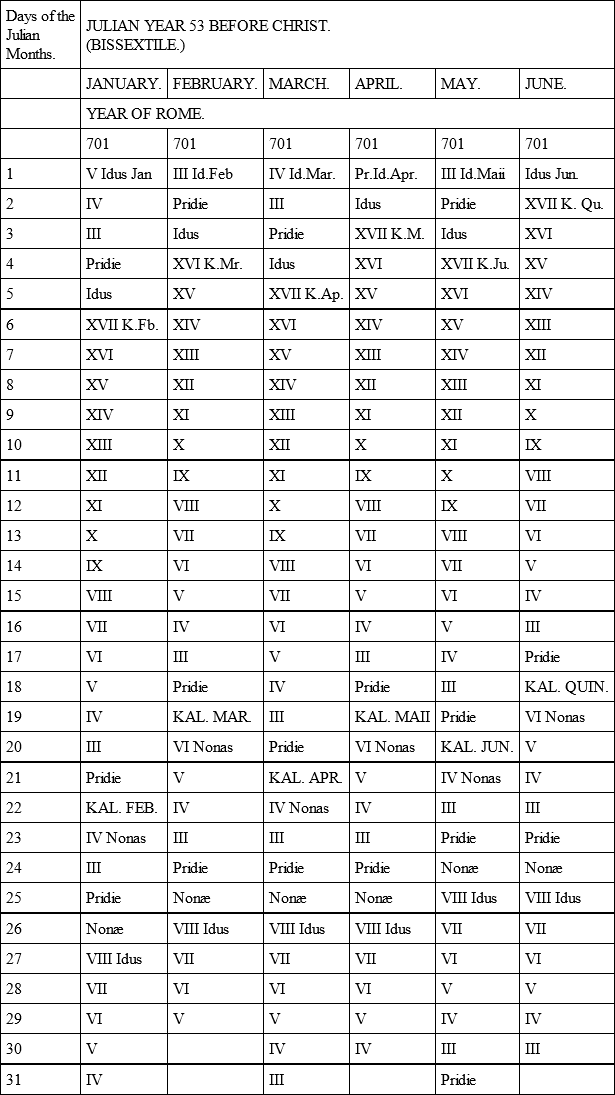

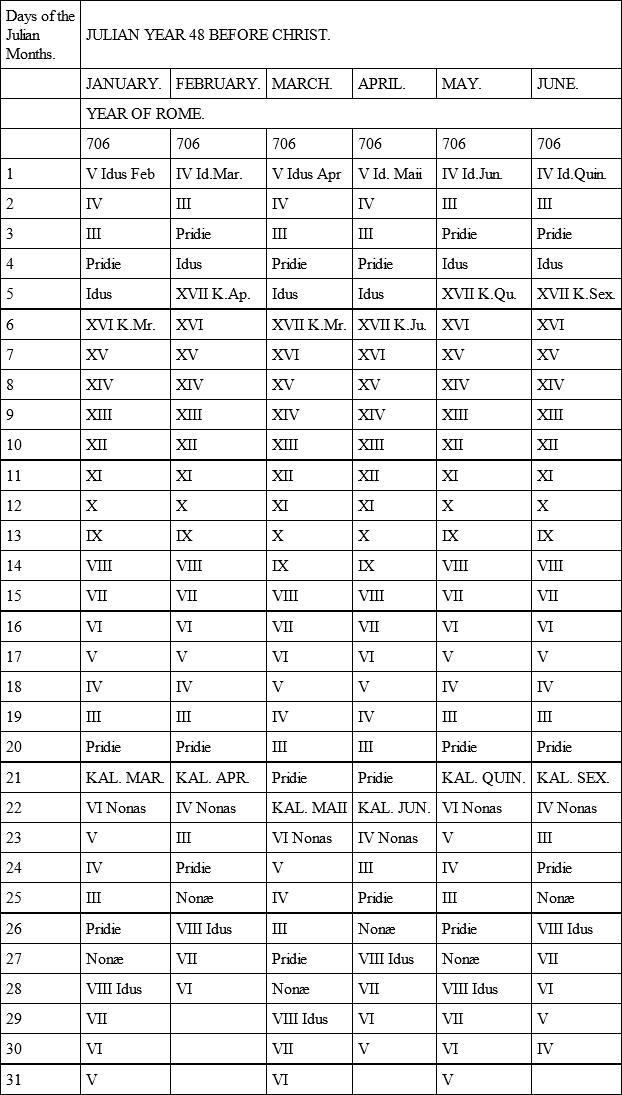

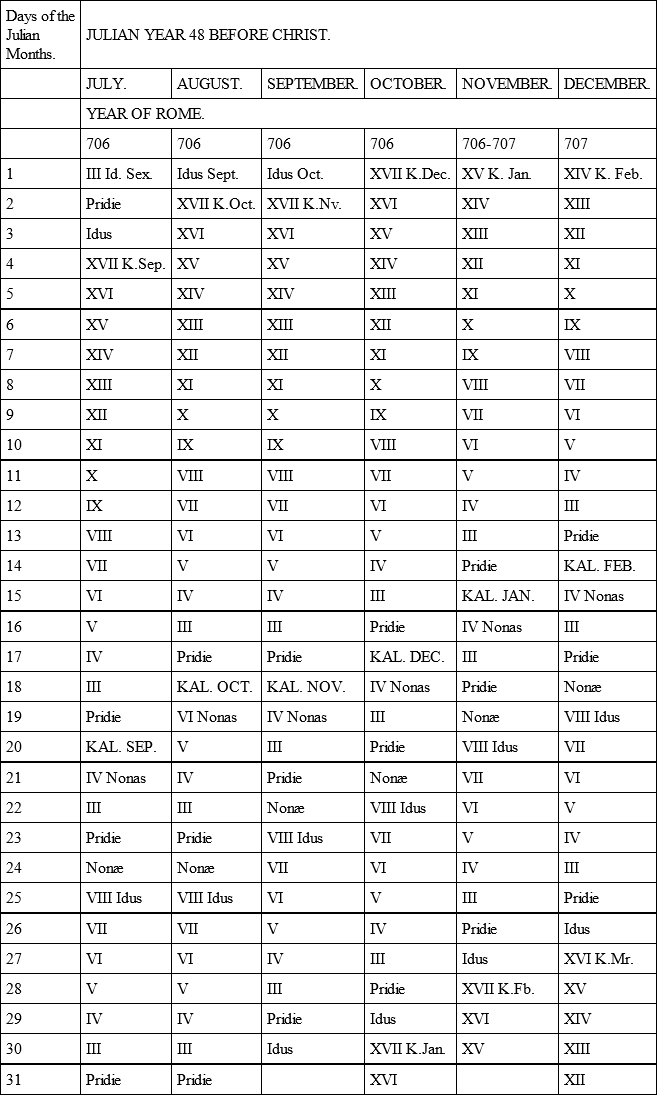

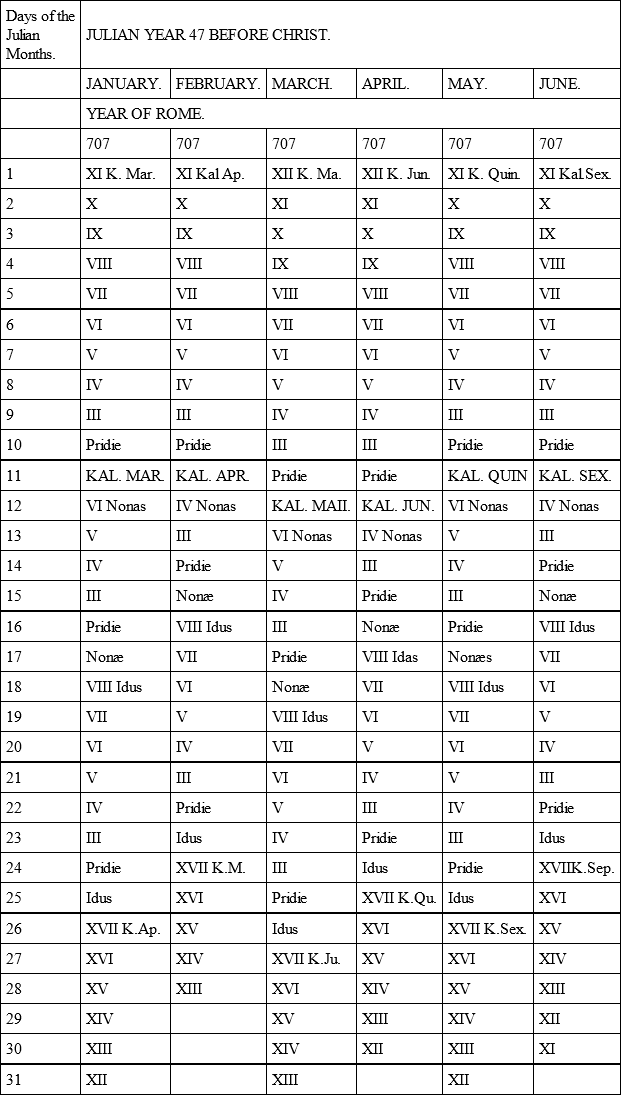

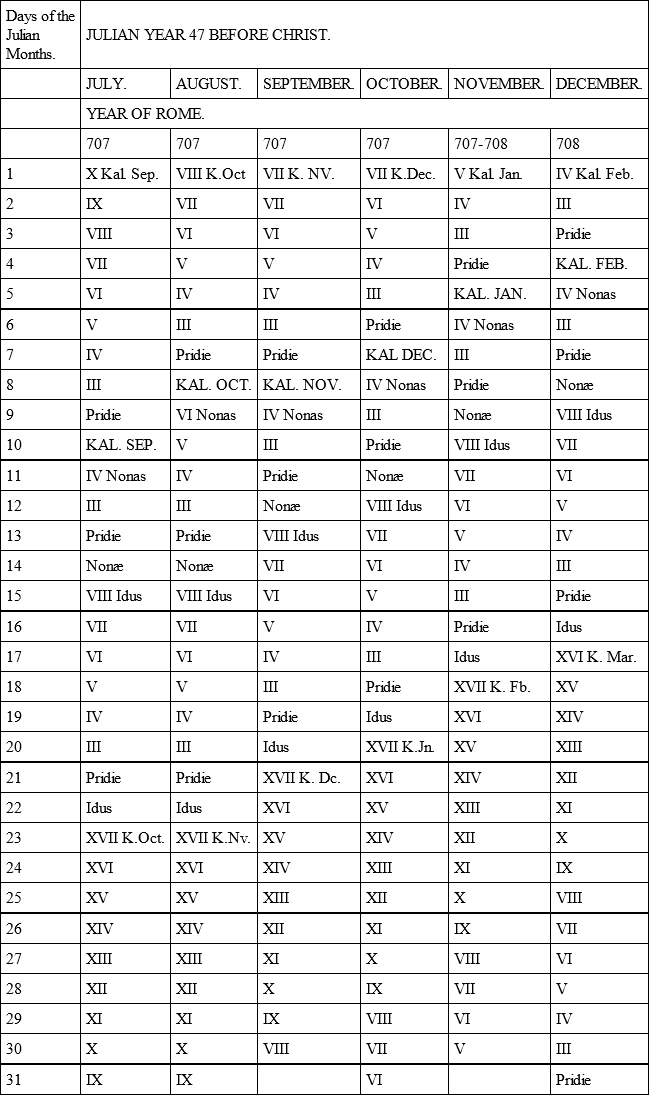

What concordance was it that required to be established thus? The 67 days necessary were exactly what required to be added that, in the secular year of Rome 700, the Julian month of March should coincide with the ancient Roman month of March. The month of March of the year 700 of Rome is the true starting-point of the Julian style.

APPENDIX B.

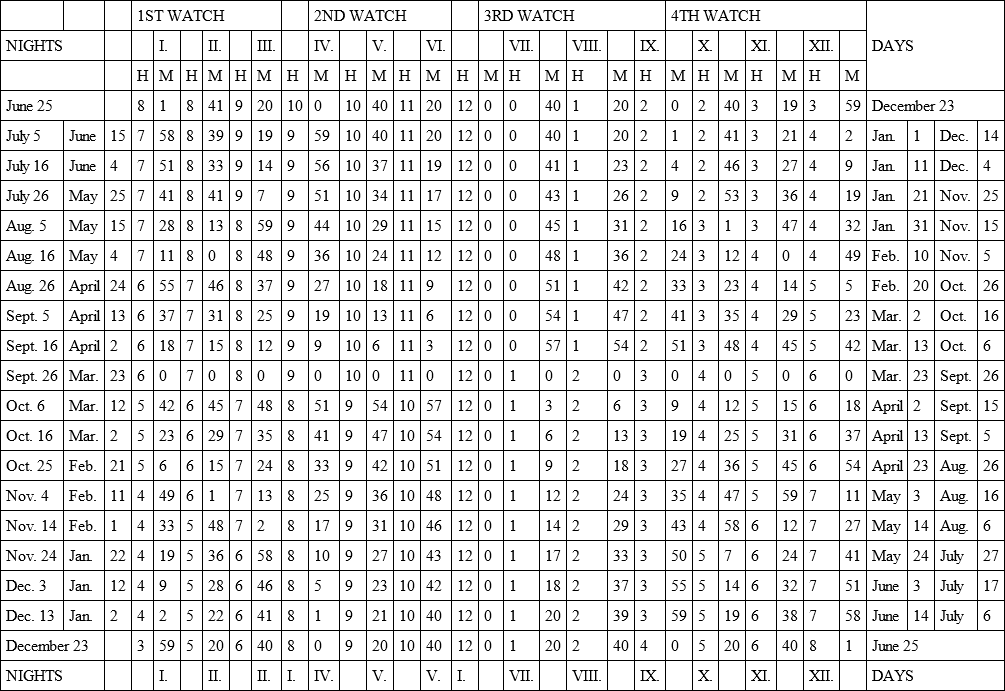

CONCORDANCE OF ROMAN AND MODERN HOURS,

For the Year of Rome 699 (55 B.C.) and for the Latitude of Paris

The dates are referred to the Julian style.

The Roman hours are reckoned from sunset and sunrise.

The modern hours are given in true solar time.

The Roman hours are given at the head of the columns, in Roman numerals. The modern hours are in ordinary numerals. Two examples will explain the use of the Table.

Division of the Night on the 16th of August.– To obtain it, we seek the date in the indicating column on the left, entitled Nights. We conclude from the line opposite: at 7h. 11m., sunset, beginning of the first hour and of the first watch; at 9h. 36m., end of the first watch and beginning of the second; at 12h. 0m. it is midnight, the second watch ends, the third begins; at 2h. 24m., end of the third watch, beginning of the fourth; at 4h. 49m. the sun rises, and the fourth watch ends.

Division of the Day on the 16th of August.– We seek the date in the indicating column to the right, entitled Days. We conclude from the line opposite: at 4h, 49m., sunrise, beginning of the first hour; the third hour ends at 8h. 25m.; the sixth, hour at noon; the ninth at 3h. 35m.; at 7h. 11m, the sun sets.

At the summer solstice, each watch embraces two of our hours; in the winter solstice, it embraces four.

APPENDIX C.

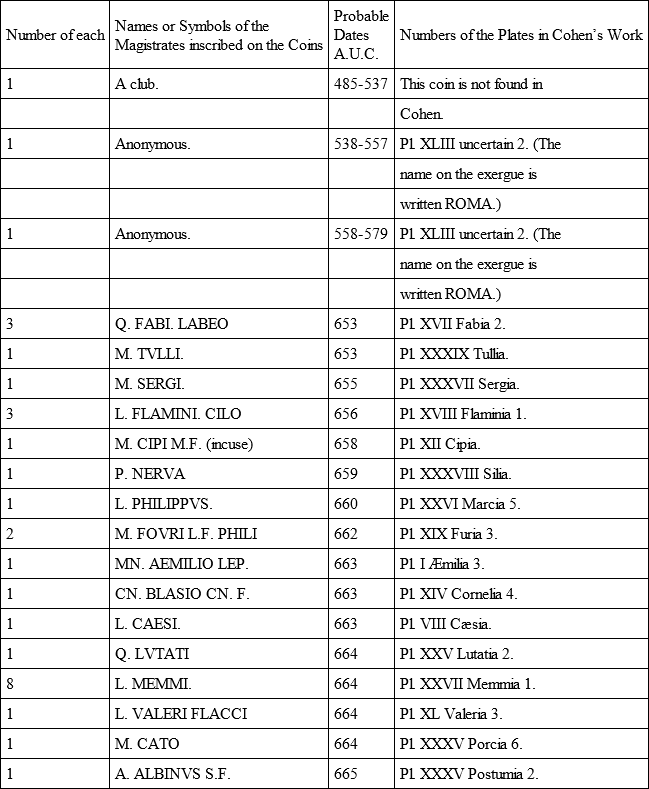

NOTE ON THE ANCIENT COINS COLLECTED IN THE EXCAVATIONS AT ALISE

THE result of the excavations made round Alise-Sainte-Reine would be sufficient to establish the identity of that locality with the Alesia of Cæsar; but the abundance of proofs can do no injury to the argument, and there is one the value of which cannot be disputed: we mean that furnished by the ancient coins found in the fosses of Camp D. (See Plate 23.) Lost in a combat, and falling into a fosse full of water, they thus escaped discovery in the immediate search made usually on a battle-field.

To establish the date of an event which has occasioned the burial of certain coins, we must first show that these coins have been struck at a period anterior to that event. Thus the coins lost at Alesia must naturally belong to a period anterior to the siege of that town.

The coins collected are in number 619; they may be divided into two distinct groups: some bear the impression of the Roman Mint, others are of the Gaulish Mint.

This being understood, let us examine separately the age of the two groups. M. le Comte de Salis and M. de Saulcy have kindly undertaken the classification.

All the Roman coins, without exception, have been struck by order and under the direction of the monetary magistrates, appointed by the government of the Republic: they belong to the republican period, and appertain to the class of coins called consular. Thanks to the labours of men like Morell, Borghesi, Cavedoni, Cohen, Mommsen, and, above all, the Comte de Salis, the age of the coins of this class is now pretty clearly determined. On the date of their emission, in general, it would be, so to say, impossible to commit an error of several years. The series of denarii and quinarii offers us the names of eighty-two magistrates, and the club, the symbol of an eighty-third; four of these denarii present neither name nor symbol; it is the same case with an as in copper, of the type of Janus with the prow of a ship, which has probably borne no other legend but the word ROMA. The most recent of these coins belong to the year 700 of Rome, or 54 B.C. The year in which the siege of Alesia took place was 702. This fact alone would serve, if needed, to demonstrate that Alise and Alesia are the same place.

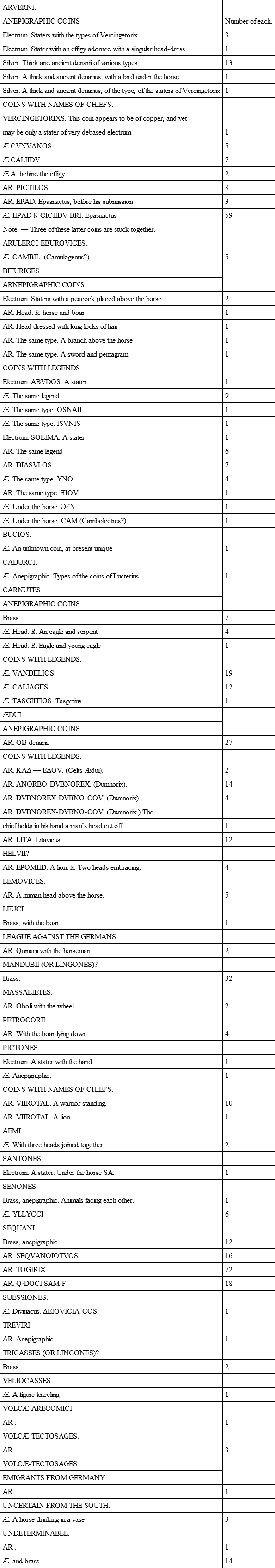

The examination of the coins of Gaulish fabrication is equally important. They belong to twenty-four civitates, or different tribes. Military contingents, assembled from all parts of the Gaulish territory, have therefore taken part in the war in which these coins were lost and scattered in the soil. But the decisive fact is, that in this number we find 103 which are incontestably of Arvernan origin; one of them bears, distinctly inscribed, the name of Vercingetorix. Of 487 Gaulish coins, 103 belong to the Arverni.

We may add that, among the latter, 61 bear the name of Epasnactus, who became, after the capitulation of Alesia, a faithful ally of the Romans, and the chief of Arvernia. (De Bello Gallico, VIII. 44.) Now the coins of Epasnactus have been long well known; they may be subdivided into two classes: some, anterior to the submission of that personage, present pure Gaulish types; others, of later date, offer only Romanised types, if we may use the expression. In the fosses of Camp D have been found only coins of Epasnactus of the primitive type. The battle in which these coins were lost by the Arverni before Alise was, therefore, anterior to the year 51 B.C., the year of the submission of Epasnactus.

LIST OF ANCIENT COINS

FOUND IN THE EXCAVATIONS AT ALISE

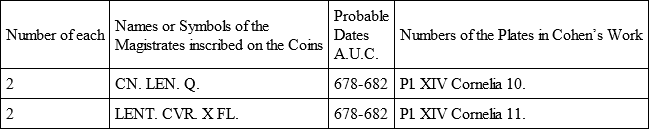

COINS STRUCK IN THE MINT AT ROME.

The coins of the social war (664-665), of the time of Marias and Sylla (666-674), and of the last two years of the war of Spartacus (682-683), are extremely common, and mostly of very rude work.

COINS STRUCK IN SOUTHERN ITALY.

This series ends with the social war in 665.

COINS STRUCK OUT OF ITALY.

These coins were struck in Spain during the war of Sertorius. No provincial coins were struck during the interval between the two civil wars from 682 to 704.

GAULISH COINS (FROM CAMP D, ON THE BANKS OF THE OSE).

APPENDIX D.

NOTICE ON CÆSAR’S LIEUTENANTS

IN his campaign against Ariovistus, Cæsar had six legions; he put at the head of each either one of his lieutenants or his quæstor. (De Bello Gallico, I. 52.) His principal officers, then, were at that period six in number, namely, T. Labienus, bearing the title of legatus pro prœtore (I. 21), Publius Crassus, L. Arunculeius Cotta, Q. Titurius Sabinus, Q. Pedius, and C. Salpicius Galba.

1. T. ATTIUS LABIENUST. Attius Labienus had been tribune of the people in 691, and had, in this quality, been the accuser of C. Rabirius. He served Cæsar with zeal during eight years in Gaul. Although he had been loaded with his favours, and had, thanks to him, amassed a great fortune (Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, VII. 7. – Cæsar, De Bello Civili, I. 15), he deserted his cause as soon as the civil war broke out, and in 706 became Pompey’s lieutenant in Greece. After the battle of Pharsalia, he went, with Afranius, to rejoin Cato at Corcyra, and passed afterwards into Africa. When Scipio was vanquished, Labienus repaired to Spain, to Cn. Pompey. He was slain at the battle of Munda. Cæsar caused a public funeral to be given to the man who had repaid his benefits by so much ingratitude. (Florus, IV. 2. – Appian, Civil Wars, II. 105. – Dio Cassius, XLIII. 30, 38.)

2. PUBLIUS LICINIUS CRASSUSPublius Licinius Crassus Dives, youngest son of the celebrated triumvir, started with Cæsar for the war in Gaul, made the conquest of Aquitaine, and was employed to conduct to Rome the soldiers who were to vote in favour of Pompey and Crassus. He quitted Cæsar’s army in 698, or at the beginning of 699. Taken by his father into Syria, he perished, in 701, in the war against the Parthians, still very young; for Cicero, attached to him by an intimate friendship (Epist. Familiar., V. 8), speaks of him as adolescens in a letter to Quintus (II. 9), written in May, 699. He was, nevertheless, already augur, and the great orator succeeded him in that dignity. (Cicero, Epist. Familiar., XV. 4. – Plutarch, Cicero, 47.)

3. L. ARUNCULEIUS COTTAThe biography of Arunculeius Cotta, before his arrival in Gaul, is not known. His name leads us to suppose that he was descended from a family of clients or freedmen of the gens Aurelia, in which the name of Cotta was hereditary. The mother of Cæsar was an Aurelia.

4. QUINTUS TITURIUS SABINUSThe antecedents of Quintus Titurius Sabinus are no more known than those of Arunculeius Cotta, whose melancholy fate he shared. His name shows that he descended from the family of Sabine origin of the Titurii, which had given different magistrates to the Republic. The name of Titurius is found on several consular medals; it is also found in some inscriptions posterior to the time of Cæsar.

5. Q. PEDIUSQ. Pedius was the son of a sister of Cæsar. (Suetonius, Cæsar, 83.) Elected ædile in the year 700 (Cicero, Orat. pro. Plancio, 7), he must have quitted the army of Gaul at the latest in 699. When the civil war broke out, he remained one of the firmest adherents of his uncle, whose interests he sustained, in 705, at Capua. (Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, IX. 14.) He was prætor when he was besieged in Cosa, by Milo, a partisan of Pompey. He was sent into Spain with Q. Fabius. (Cæsar, De Bello Civili, III. 22; De Bello Hispan., 2. – Dio Cassius, XLIII. 31.) Made by Cæsar’s will the heir of one-eighth of his wealth, he gave up what was left to him to Octavius. (Suetonius, Cæsar, 83. – Appian, Civil Wars, III. 94.) It was at the motion of Q. Pedius, then consul, that the law was passed which has received its name from him, and which was directed against the murderers of the Dictator. (Velleius Paterculus, II. 65. – Suetonius, Nero, 3.) Q. Pedius remained faithful to Octavius, yet he proposed the retractation of the declaration of war launched against Antony and Lepidus. He was admitted to the secret of the triumvirate, which was on the point of being concluded, and died suddenly before the end of the year 711. (Dio Cassius, XLVI. 52 – Appian, Civil Wars, IV. 6.)

6. SERVIUS SULPICIUS GALBAServius Sulpicius Galba, whom the Emperor Galba reckoned among his ancestors, was of the illustrious family of the Sulpicii; he descended from Sulpicius Galba, consul in 610, who had left the reputation of a great orator. S. Sulpicius Galba, Cæsar’s lieutenant in Gaul, had already served in the war in that country under C. Pomptinus, in 693 (Dio Cassius, XXXVII. 48), which explains the choice made of him by the future Dictator. He must have quitted Cæsar’s army at latest in 699, for he was, at his recommendation, elected prætor in 700. (Dio Cassins, XXXIX. 65.) He solicited the consulship in vain in 705. Pressed by the creditors of Pompey, for whom he had made himself surety, he was relieved from his difficulties by Cæsar, who paid his debts. (Valerius Maximus, V. 2, § 11.) Finding himself finally deceived in his hope of arriving at the consulship, S. Galba joined the conspiracy against his old chief. (Suetonius, Galba, 3. – Appian, Civil Wars, II. 113.) He served in the war against Antony, under the Consul Hirtius. We have a letter from him to Cicero, written from the camp of Modena. (Cicero, Epist. Familiar., X. 30.) Prosecuted, in virtue of the law Pedia, as a murderer of Cæsar, (Suetonius, Galba, 3), he was condemned, and died probably in exile.

The Senate granted Cæsar, in 608, ten lieutenants: Labienus, Arunculeius Cotta, Titurias Sabinus, already in Gaul, Decimus Brutus, P. Sulpicius Rufus, Munatius Plancus, M. Crassus, C. Fabius, L. Roscius, and T. Sextius. As to Sulpicius Galba, P. Crassus, and Q. Pedius, they had returned to Italy.

7. DECIMUS JUNIUS BRUTUSDecimus Junius Brutus, belonging to the family of the Junii, was son of Decimus Junius Brutus, elected consul in the year 677, and of Sempronia, who performed so celebrated a part in Catiline’s conspiracy. He was adopted by A. Postumius Albinus, consul in 655, and took, for this reason, the surname of Albinus, by which we find him sometimes designated. When Cæsar took him into Gaul, he was still very young; the “Commentaries” apply to him the epithet adolescens. He must have returned to Rome in January, 704, since a letter of Cicero mentions his presence there at that period. (Epist. Familiar., VIII. 7.) The year following he commanded Cæsar’s fleet before Marseilles. (Cæsar, De Bello Civili, I. 36. – Dio Cassius, XLI. 19.) He gained, although with unequal forces, a naval victory over L. Domitius. (Cæsar, De Bello Civili, II. 5.) Having received from Cæsar, in 706, the government of Transalpine Gaul, he repressed, in 708, an insurrection of the Bellovaci. (Titos Livius, Epitome, CXIV.) An object of the special favours of his old general, who felt for him a warm affection, D. Brutus, along with Antony and Octavius, was associated in the triumph which Cæsar celebrated in 709, on his return from Spain, and mounted with them on the car. (Plutarch, Antony, 13.) By his will of the Ides of September, the Dictator named him one of the guardians of Octavius, and made him one of his second heirs (Dio Cassius, XLIV. 35. – Appian, Civil Wars, II, 143. – Suetonius, Cæsar, 83); he caused to be given him, for the year 712, the government of Cisalpine Gaul. In spite of this friendship, of which Cæsar had given him so many proofs, and which the latter believed to be paid by a requital, Brutus, who had remained faithful to his benefactor in the civil war, lent his ear to the proposals of the conspirators, and yielded to the seductions of M. Brutus, his kinsman. He not only went to the Senate to assist in striking the victim, but he accepted the mission of going to persuade the Dictator, who was hesitating, to repair to the curia. (Dio Cassius, XLIV. 14, 18. – Appian, Civil Wars, II. 115. – Plutarch, Cæsar, 70.) Exposed to public hatred (Cicero, Philippic., X. 7), and intimidated by the threats of Antony, he left Rome to go and take possession of the province which Cæsar had caused to be assigned to him. (Cicero, Epist. ad Atticum, XIV. 13.)

He appears, however, to have acted but feebly in favour of the party he had embraced. Antony, having obtained from the people, in exchange for Macedonia, the province commanded by Brutus (Appian, Civil Wars, III. 30), the latter refused to abandon his government, and, supported by Cicero, he obtained from the Senate an edict maintaining him in it (Cicero, Philippic., III. 4. – Appian, Civil War, III. 45), which led to an armed contest between the two competitors. Pursued by his rival, Brutus threw himself into Modena, and there sustained a long siege (Appian, Civil Wars, III. 49. – Titus Livius, Epitome, CXVII), which had for its final result the celebrated battle in which Antony was defeated. D. Brutus, overlooked among new actors in this sanguinary drama, remained in it almost a mere spectator. (Dio Cassius, XLVI. 40.) He then ranged himself on the side of Octavius, yet without the existence of any very close or very sincere intimacy between these two men. He continued to exercise an important command during the war, but fortune was not long in turning against him. Pressed by Antony, who had united with Lepidus, and threatened personally by the prosecutions which Octavius, armed with the law Pedia, was directing against the murderers of Cæsar (Titus Livius, Epitome, CXX. – Dio Cassius, XLVI. 53), he found himself deserted by his troops, and, after a vain attempt to cross into Macedonia, he directed his steps with a small escort towards Aquileia; but a Gaulish chief, named Camillus, betrayed towards him the rites of hospitality, kept him prisoner, and sent information of what he had done to Antony. The old lieutenant of Cæsar immediately sent Furius with a party of cavalry, who slew Brutus, and carried away his head. (Appian, Civil Wars, III. 97, 98. – Velleius Paterculus, III. 63, 64.) Brutus was one of the correspondents of Cicero, who gives him praise, especially for his constancy in friendship, of which he was certainly little worthy.