полная версия

полная версияSocial Origins and Primal Law

Between these the primal law of celibacy between brother and sister as such embraced the whole generation. Now as long as the family was thus simply constituted, no friction would arise. The brothers, in common, captured and married in common some outside female,326 and their children constituted solely the next generation. The sisters were either stolen or emigrated to other groups; but we have seen that a moment would come when this process ceased to be universal. The sister came to remain in her own group, and she was joined by some outside suitor; with the advent of their children, who are cousins to the others, would arise dire perplexities, in view of the old law.

We may now begin to see more distinctly, in the fact of the presence of the cousins, the resolution of the problem as to how a sister's son came to be also a brother's, and we will find that Mr. Morgan was not the first to be baffled by the problem. It was too intricate for primitive man at any rate. When first presented to him, we may surmise that he, in fact, refused to recognise it as a problem at all. Since the beginning of things in the group, as constituted by all tradition, the children of one generation were children of another simply, and nothing more. That as a result of the presence of the outside male, some intricate process of scission had occurred, and things were not as they seemed, was an idea far too abstract to be readily seized. All in a generation had been ever, to early man, brother and sister, and brother and sister they should continue.

We have seen in a past chapter that it was actually to the interest of senior male group-members, while incest reigned, that this condition of things should endure. It put at their sole disposal the daughters of their brothers-in-law, and in the primal law placed a ban on sexual intercourse between all the younger male and female members, as constituting them brothers and sisters. As a factor in this case, however, the effect of incest was more or less temporary. The real agent in the tardy or non-recognition of the cousinship thus created, was the conservative force of old habit and tradition. We must remember that, in so early a group, personal descent as such was in no way recognised. Mere local contiguity alone constituted the sense of relationship, exogamy for instance took the form of local exogamy, for as all within a locality were (locally) relations, so all outside were, as strangers, free in marriage. While then so strong a sense of the value of contiguity continued, and was in practice, the evolution of an idea of non-relationship of two individuals with a common habitat would be too complex. Again, a recognition in fact implies a vast modification of the whole organisation of the group, which thus contains in cousins the elements of marriage within itself. But this is the latest and highest type of group and constitutes the tribe. We can understand that such a step was not taken at once by early man. Even when recognised we know that definition lags behind the event.

Thus in such a case as cited, and at the stage we are studying, if we find two cousins in presence, who are yet unrecognised as cousins, then, if nomenclature has taken place, we should find exactly the terms employed in the Malayan table which misled Mr. Morgan. A sister's son would be termed the brother's son, simply because the individual was as yet ignored, although existent, as a cousin, as members of the same generation they were brother and sister. Classes by generations alone were recognised.

Now as regards the validity of our assumption that relativity in age served as a means to determine privilege as to wedlock, proof can be furnished by certain nomenclatory features, as between members of a class or generation, to be found in the Malayan table in Ancient Society and elsewhere. This will afford, incidentally, strong negative proof of our theory as to non-union between brother and sister. It will also incidentally furnish the strongest negative evidence that, so far from brother and sister living in incest, as Morgan holds, brother and sister were regarded as quite apart in the sense of any sexual relation between them. It will be seen that there is a profound distinction made in address between inter-marriageable people and those between whom celibacy is enjoined.

Both Mr. Morgan and Mr. McLennan have drawn attention to the peculiarities in the terms of address as between 'brothers' and as between 'sisters.' It is curious that the full significance of the phenomena therein presented escaped two such keen intellects. We find here that terms of address as between persons of the same sex and of the same generation, and ergo brothers or sisters, present the very remarkable features that

(1) 'The age of the person spoken to compared with that of the speaker plays a very important part in the matter of denomination.'

(2) 'Such names refer not to the absolute age of the person addressed.'

(3) 'The relationships of brother and sister are conceived in the twofold form of elder and younger, and not in the abstract, and there are special terms for each among the Seneca Iroquois.'

(4) 'There is no name for brother and sister (Malayan system). On the other hand, there are a variety of names for use in salutations between "brother" and "sister" according to the age and sex of the person speaking in relation to the age and sex of the person addressed.'

(5) Among the Eskimo the form of the terms of relationship appears to depend, in some cases, more on the sex of the speaker than on that of the person to whom the term refers.

(6) In Eastern Central Africa, if a man has a brother and a sister, he is called one thing by the brother, but quite a different thing by the sister.

We will now illustrate the idea more completely by an extract of terms from the table of Hawaiian relationships in Ancient Society. An older or a younger brother is to a sister simply addressed or mentioned by the general term Kaiku nana, but to her, in address or mention of an older or a younger sister, they are respectively Kaik a'ana and Kaika-i-na. Again, an older or a younger sister is to a brother collectively Kaikuwaheena, but to him an elder or a younger brother is respectively Kaiknana and Kaikaina.

Now in view of our argument as regards the origin of these diversities in some sexual feelings, it is a most significant feature in these details of the terms of address that the expression of the relativity of age between the speakers is confined solely to the intercourse between members of the same sex. That a brother is the senior or the junior of Ego is carefully noted, but a sister is simply and vaguely a sister. Why? simply because whereas, by virtue of the primal law, no possible question whatever of mutual interest in sexual matters could possibly arise between a brother and a sister, on the other hand friction might hourly occur between brothers or between sisters. In fact, if our theory is correct, then, as questions of sexual privilege or precedence could cause jealousy between members of the same sex, distinctions would be necessary by definition of seniority when address took place between these, and in these cases alone, and this indeed we find to be the fact. As conclusive evidence we would cite the further important fact that these very same distinctions of senior and junior are used, inter se, between all those of the same totem [phratry] as now existing, but are never employed for their tribal cousins of the other totem [phratry]. And the reason is the same. The latter naturally do not marry (in groups formed of only two classes) [phratries] into the same totem [phratry] as the former, and thus there is no cause for jealousy or necessity of definition, whereas individuals of the same totem [phratry] are ipso facto group [potential] husbands of the same group [potential] wives, or are at least eligible in marriage with the same totem groups [phratries], and hence necessity for the exact definition by age of each one's rights.

Thus, as with other laws or institutions we have traced, we find a desire for distinction as regards rights in sexual union to be the genetic cause of the classificatory system both as regards the generation and its component members.

In all periods of transition which a process in change in progress implies, we expect to find cases where the conservative force of tradition from the past has delayed recognition of the too novel present, and we discover that circumstances have moved too rapidly for the intelligence of the times. If we keep this fact in view, we have thus seemed to find a natural explanation of the knotty point which was the cause of dispute between Mr. Morgan and Mr. McLennan,327 and we may thus venture to say that each was both wrong and right in his views of the classificatory system in general. Each has mistaken a part for a whole, and they were ignorant that they were upholding two sides of the same question. Mr. Morgan was in error in assuming the system's too intimate connection with a determination of affinities in blood, in relation to which primarily, as we hope to have shown, it had really neither purpose nor aim, as also in his too hasty assumption of a consanguine family founded on brother and sister incest, based on a mere conjectural solution of a verbal detail, an assumption which he himself acknowledges had no other foundation.

Mr. McLennan was in error in maintaining that the classificatory system concerned terms of address alone. To quote his own words: 'What duties or rights are affected by the "relationships" comprised in the classificatory system? Absolutely none; they are barren of consequences, except indeed as comprising a code of courtesies and ceremonial addresses in social intercourse.' On the other hand, as we have tried to show, the system had precisely both intention and effect in regulation, as regards sexual feeling, which is the strongest passion in nature. And yet each disputant again was right in a degree, for, in later times, the classificatory distinctions really served as terms of address as regards the clan [tribe?], whilst again the primitive terms, which simply describe generations of persons in their relation to the group, were afterwards, by philological transmutation, to come to have a more definite meaning expressing the sense of the personal parent.

NOTE TO CHAPTER VIIIGroup MarriageThe idea that 'group marriage' exists among the dusky natives of Australia, and that 'the group is the social unit as regards marriage' (as explained in the earlier part of this book), was introduced by Messrs. Howitt and Fison in their Kamilaroi and Kurnai (1880). Messrs. Spencer and Gillen, in their Natives of Central Australia (1899), support the views of Messrs. Fison and Howitt. 'Under certain modifications group marriage still exists as an actual custom, regulated by fixed and well recognised rules, amongst various Australian tribes' (p. 56). 'Individual marriage does not exist either in name or practice in the Urabunna tribe' (p. 63). Mr. Crawley argues, on the other hand, that individual marriage does exist among the Urabunna, 'though slightly modified' (Mystic Rose, p. 482). For each 'slight modification,' the husband's consent must be obtained. The system is regarded by Mr. Crawley, not as a survival of promiscuity, more or less modified, but as an 'abnormal development.' He believes in individual marriage, as, from the earliest known times, 'the regular type of union of man and woman.' 'One is struck by the high morality of primitive man' (pp. 483-484).

What Mr. Atkinson meant by saying that 'marriage is communal,' I do not understand, as, on his theory, sexual jealousy must have prevented each man of a generation, in a group, from being equally the husband of each woman, not his sister. The young braves are supposed to bring in women captives from without, and to marry them 'communally,' Then what becomes of jealousy? They ought rather to have fought for their captive, on the principles of a golf tournament, the survivor and winner taking the bride. Mr. Atkinson never saw his work except in his manuscript, and might have made modifications on such points as this, where he seems to me to lose grasp of his idea, as in his theory of recognition of the children of 'the outside suitor,' he seems to bring male descent into action at a period when, as he asserts elsewhere, it was not yet recognised by customary law. On the Keddies (p. 287) I have no information, the author giving no reference. A. L.

APPENDICES

APPENDIX A

ORIGIN OF TOTEMISM

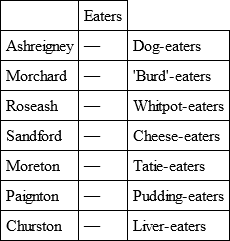

In the following village sobriquets from the south-western counties of England the people are styled 'eaters of' this or that.328

ENGLISH VILLAGE SOBRIQUETS

Compare with these the following sobriquets of Siouan old totem kins, counting descent in the male line.

SIOUAN NAMES OF GENTESEaters

Eat the scrapings of hides

Eat dried venison

Eat dung

Eat raw food

Among the Sioux we have also noted the sobriquets

Non-Eaters of

Deer

Buffalos

Swans

Cranes

Blackbirds, etc.

These sobriquets of non-eaters are probably totemic: the Deer kin does not eat deer, nor does the Crane kin eat cranes, and so on. Totem kins are named from what they do not eat; many totem kins with male descent are nicknamed from what they do eat, or are alleged by their neighbours to eat.

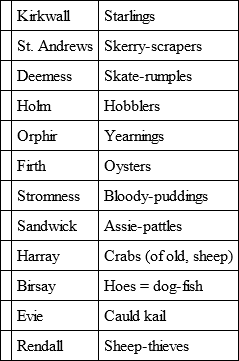

GROUP SOBRIQUETS IN ORKNEYIn the following letter, which I owe to the kindness of Mr. Duncan Robertson, we read that, in Orkney and Shetland, local sobriquets are derived from what the people are alleged to eat. The tradition is, Mr. Robertson informs me, that each group is named after the edible plant or animal which it brought when engaged in building the Cathedral of Kirkwall.

Crantit House, St. Ola,Orkney,Jan. 29, 1903.Dear Mr. Lang, – My tyrannical doctor won't let me out yet, so that I have not been able to collect all the information I should like to get for you about the Orkney nicknames – or 'bye-names,' as they are called here.

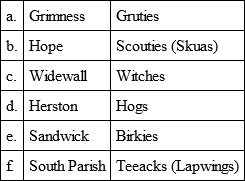

Here follows the list as taken from Tudor's The Orkneys and Shetland, with alterations:

I. MAINLAND OR POMONA

II. SOUTH ISLES

South Ronaldshay

III. NORTH ISLES

These are all the names I know or can hear of in Orkney. I wrote to Mr. Moodie Heddle of Cletts on the subject, as I knew him to take a great and intelligent interest in all such topics; and I have a most interesting letter from him, of which I shall give you the gist. He says he has no doubt that the origin of the names is that which you suggest, though some of the names do not at first sight appear to bear this out. Kirkwall 'Starlings' are easily accounted for, assuming that there have always been as many starlings about Kirkwall as there are now. They may well have been eaten by the townsfolk. I have tried them, and their breasts are not at all bad.

Skerry-scrapers. – The allusion here is to men who live off shell fish, 'dilse,' etc. off the skerries. There are – or were – excellent oysters on the St. Andrews skerries. Mr. Heddle tells me he has heard a woman insulting a man by saying she supposed he would soon leave no limpets in a certain bay, meaning that he was too lazy to work for his living.

Skate-rumple is, of course, the skate's tail. Deemess is the nearest land to a famous piece of water for skate, known as 'the skate-hole.'

Holm 'Hobblers' I do not understand, but shall make some further inquiries. I have an idea it is a reference to some bird; Mr. Heddle thinks it has something to do with seals, but neither of us knows.

Yearnings are, of course, the dried stomachs of calves used for making cheese.

Oysters. – The bay of Firth was famous for its oysters till the beds were overfished and destroyed some thirty years ago.

Stromness 'Bloody-puddings'– Mr. Heddle suggests that the people bled their cattle twice or thrice a year and made 'puddings' of the blood. This, of course, was done in the Highlands at one time.

Assie-pattles. – Either those who lay in the ashes or, Mr. Heddle suggests, who ate cakes baked in the ashes. Before iron girdles came much into use cakes were baked on flat stones; and there is a hill, known as 'Baking-stone Hill,' where the people used to come for stones that would not split in the fire. The peats used in Sandwick have a very red ash, which colours all persons and things near it.

Harray 'Crabs.'– Harray is the only parish in Orkney which does not touch the sea, and the name is given in irony. The old 'tee-name' is said to have been 'sheep.' The story is told that some fishermen passing through Harray dropped a live crab. The men of Harray could not make it out at all, and sent for the oldest inhabitant, who was brought in a wheel-barrow. After gazing at the monster for a few moments he exclaimed: 'Boys, hid's a fiery draygon; tak' me hame!'

I suspect there is some other tee-name than 'sheep-thieves' for the Rendall people, but will try to find out and let you know.

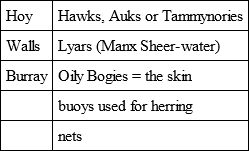

Hoy 'Hawks'– Mr. Heddle, who was formerly proprietor s²xof Hoy, says he thinks 'auks' must have been the original word, as he believes 'tammy-nories' was the old name. 'Auk' is Orcadian for the common guillemot, and a 'tammy-norie' is a puffin. Both of these birds abound in Hoy.

Mr. Heddle also tells me that the old name of 'Lyars' for the people of Walls was to a great extent replaced by 'Cockles.' The 'lyars' were very common in Walls at one time, and were esteemed a great delicacy, but, Mr. Heddle tells me, were to a great extent killed out by the brown rat. He himself remembers men being bitten by rats when putting their hands into holes to look for young 'lyars.' Some three generations back enormous numbers of cockles were taken and eaten by the people of Walls, and they seem to have been called 'Cockles' – or, I presume, 'eaters of cockles' – in consequence.

Oily Bogies. – I hardly see how this can have been 'eaters of.' There might have been some old story to the effect that the Burray men stole and ate these buoys, but I never heard it.

South Ronaldshay has names for every district, which no other island but the Mainland has.

Gruties is, Mr. Heddle says, equivalent to 'Skerry-scrapers' – people who get their living from the 'grut' or refuse left in bights by the tide. ('Grut,' see Norse gröde = porridge or gruel.)

Scouties may be derived from the skua, though Mr. Heddle gives an unpresentable derivation. The word Birkies he did not know the meaning of, but asked two or three people, who all said the Sandwick people were so called 'because Sandwick was such a place for tangles coming ashore, and the people had such a habit of eating what they called "birken" tangles, i.e. the stout or lower ends of the large thick tangles.'

Burstin Lumps are a sort of preparation of oatmeal, once a very favourite dish in the Isles.

Rousay 'Mares'– There is an old tale of a Rousay man who, being a coward, killed his mare and hid inside her from his enemies. Mr. Heddle sends me an old rhyme on the subject:

As the Rousay man said to his mare:'I wish I were in thee, for fear o' the war;I wish I were in thee without any doubt,Were it Martinmas Day before I cam' out.'The North Ronaldshay people did eat seals. Why Hides I do not know. Mr. Heddle here suggests it may have had to do with witchcraft, in which skins and especially seals' flippers were much used. Within the last ten years a man pulled down and rebuilt his byre because of some 'ongoings with a selkie flipper.'

The names are very old and must be of Scandinavian origin.

Yours sincerely,DUNCAN J. ROBERTSON.In addition to these names of 'eaters,' simple names of animals, we have shown in the text, are as commonly given to English villages as totemic names are given to the totem groups of savages.

ANCIENT HEBREW VILLAGE NAMESIn Robertson Smith's Kinship and Marriage in Early Arabia (p. 219) he says: 'I have argued that many place-names formed from the names of animals are also to be regarded as having been originally taken from the totem clans that inhabited them.' Now where totemism is a living institution I know no instance in which a locality is named from 'the totem clan that inhabits it.' The thing cannot be where female descent prevails, as many totems are then everywhere mixed in each local group. Where male descent prevails we do, indeed, get localities inhabited by groups mainly of the same totem name. But their tendency is to let the totem name merge in the territorial title, the name of the locality, as Messrs. Spencer and Gillen prove for the Arunta and Mr. Dorsey for the Sioux.

Having found no instance where a totemic group gives its totem name to the locality which it inhabits, I was struck by a remark of Dean Stanley in his Lectures on the History of the Jewish Church (p. 319, 1870). He there mentions the villages of Judah which were the scenes of some of Samson's adventures (Joshua xv. 32, 33; Judges i. 35). The villages of Lebaoth, Shaalbim, Zorah, respectively mean Lions, Jackals, and Hornets. Nobody eats any of these three animals, and they may be names of totem groups transferred to localities – though of this usage I know no example among savage totemists – or they may merely be old Hebrew village sobriquets, as in England and France.

On consulting the Encyclopædia Biblica, under 'Names' (vol. iii. 3308, 3316) we find that 'there can be no doubt that many place-names' in Palestine 'are identical with names of animals.' Those 'applied to towns' (we may read villages probably) are much more common in the south than in the north. We have Stags, Lions, Leopards, Gazelles, Wild Asses, Foxes, Hyænas, Cows, Lizards, Hornets, Scorpions, Serpents, and so on. These may have been derived from old totem kins, though I think that theory improbable, or from the frequency of hornets or scorpions in this or that place, or the villagers' sobriquet may have become the village name. The last hypothesis has hitherto been overlooked. The frequency of animal and plant names in the Roman gentes, Fabii (Beans), Asinii (Asses), Caninii (Dogs), is an instance that readily occurs. These may be survivals of totemism or of less archaic sobriquets, while the totem names themselves, as we have argued, may have had their origin in sobriquets.

APPENDIX B

THE BA RONGA TERMS OF RELATIONSHIP

The hypothesis that the Australian terms of relationship, as they now exist, really denote status in customary law, may perhaps derive corroboration from the classificatory system as it appears among the Ba Ronga, near Delagoa Bay. Here the natives are rich, industrial, commercial, and polygamous to the full extent of their available capital. Polygamy, male kinship, and wife purchase, with elaborate laws of dowry and divorce, have modified and complicated the terms of relationship. They are described by an excellent authority, M. Henri Junod, a missionary.329

M. Junod has obviously never heard of the 'classificatory system' among other races, and his explanation of certain 'avoidances,' such as between the husband and his wife's brother, father, and mother, is probably incorrect (turning, as it does, on the laws of wife-price and divorce), though it appears now to be accepted by the Ba Ronga themselves. But what more concerns us is the nature of terms of relationship. These terms denote status in customary law, determined by sex and seniority. Among the Basuto, 'a man is otherwise related to his sister than to his brother; his children are related to their paternal otherwise than to their maternal uncles and aunts,' and to their cousins in the same style. Relative seniority, entailing relative social duties, is also expressed in the terms of relationship. The maternal aunt, senior to the mother, is 'grandmother.' The children of my father's brother and of my mother's sister, are my 'brothers' or 'sisters;' the children of my maternal uncle and paternal aunt are not my 'brothers' and 'sisters.' The children of a man's inferior wives call the chief wife 'grandmother,' and the other wives, not their mother, 'maternal aunts.'330 The son of my wife's sister is my 'son,' because I may succeed to her husband on his death, and his father calls me 'brother.' The maternal uncle is the mere butt of his nephew, the uncle's wives are the nephew's potential wives: he is one of the heirs to them. This kind of uncle (maternal) is not one of the tribal 'fathers' of the nephew, but the paternal uncle is, and is treated with the utmost respect. In brief, each name for a 'relationship' is a name carrying certain social duties or privileges, dependent on sex and seniority.