полная версия

полная версияSocial Origins and Primal Law

However, in connection with our argument we have Adolf Erman's account of the custom among the Yakuts, and where we find the husbands elder brother joined with the father-in-law in an avoidance, there a distinct feeling of impropriety in connection with these relations in law of the wife is indicated. The diffidence cited is exactly what would occur if union was undesirable and yet not impossible, between the persons in avoidance, and hence temptation was to be avoided. It is very important to note that no idea of enmity from capture can be associated with the husbands elder brother. Again, the custom of avoidance with an elder brother, where its connection with jealousy is evident, is very widespread, and very strict in observance; as we have already noted, it occurs in Orissa and among the Kyonthas in India, whilst I have also observed it in practice in New Caledonia, where it is most undoubtedly a means to an end, to protect the younger brother's marital rights. As to the significance of the fact mentioned in the case of the natives of Australia, where, as regards their wives, they are jealous of a man – and give him a daughter to place him in avoidance with her mother, comment is unnecessary.

These facts seem to me to be conclusive; but the question of the exact origin of avoidance is so important to my general argument, that I am glad to be able to find what I fancy is added proof from another source. If this furnishes the requisite evidence that sexual jealousy was the real factor, and not hostile capture, our hypothesis of the primal law acquires valuable inferential evidence in its favour. Such added proof we hope to be able to show in Dr. Tylor's figures.314

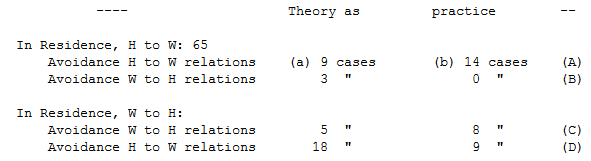

These figures, which are extracted from Dr. Tylor's work, would seem to be eloquent against hostile capture being the sole cause of Avoidance. They are derived from a comparison of Avoidance as occurring, (a) quite independent of residence, and (b) as actually resulting where coincidence of Avoidance and residence is found.

Now as regards the question of jealousy as cause of Avoidance, residence and propinquity will evidently have a powerful effect.

(A) As we have seen, any Avoidance under these circumstances would be remarkable without a prior stage in quite other conditions than those found generally with H to W residence. We note that whereas we might expect under even the above conditions to find only 9, there are 14. Here sexual jealousy has been an important cause.

The Avoidance of the Mother-in-law (for, of course, there was none here with father-in-law, who was a nonentity in such a family circle, and of the same clan as the son-in-law) arose as a matter of protection for the marital rights of the daughter as against her mother, both inhabiting the same large house common to matriarchal descent.

(B) Here, again, we expect to find 3, and see there are actually none, from which it would seem to result that W capture had nothing whatever to do with the origin of A, H to W, for, admitting the almost entire separation of the W from H family, which would make the case rarer, a tradition of capture would exist which would have effect when they were later grouped together. Whereas the non-Avoidance is explained by lack of jealousy, from absence of male relations of H.

(C) Here it is again quite impossible to accept any idea of W capture as the motive cause. Avoidance arose between W and father-in-law to protect rights of son-in-law and mother-in-law. It was evolved, as we have seen, as a measure of protection for that generation of males who were the actual captors, each generation by the classificatory system having individual rights. That the necessity for such legislation was urgent we see in the proportion of the figures 5 to 8.

Here, again, the fallacy of capture as primal cause of Avoidance is clearly evident. If this was the case, we might expect it to be almost universal, whereas in reality, instead of the 18 cases which the average should give us, we find only 9. It really had its origin in the reason we have already given, of sexual jealousy as a primary cause, and was later augmented as serving to impress on many the classificatory distinction between M and D, who otherwise, as far as totems went, were eligible to the same person. Where both father-in-law and mother-in-law are in avoidance, we may surmise a change in descent from the F to the M in the tribe, the converse change of M to F of course never occurring. The question of change of descent will explain problems in the nomenclature of Morgan's tables as regards nephews and sons, which have been overlooked.315

NOTE TO CHAPTER VIIMr. Crawley reckons three interpretations of the origin of the avoidance of mother-in-law and son-in-law. 1. Fison (Kamilaroi and Kurnai, p. 103), 'It is that the rule is due to a fear of intercourse which is unlawful, though theoretically allowed on some classificatory systems.' Mr. Crawley remarks, 'this explanation is the one most likely to occur to explorers who have personal knowledge of savages,' which was Mr. Atkinson's case. Mr. Crawley objects the antecedent improbability of any man, 'not to mention a savage, ever falling in love with a woman old enough to be his mother or mother-in-law, and the improbability of so many peoples being afraid of this.' Now 'in love' is one thing, and an access of lust is another. Moreover, the mother-in-law, in prospective, not infrequently is her daughter's rival, even in modern life. She has to be guarded against, even if the son-in-law is less dangerous. And he is very apt to be 'a general lover.' 'Theoretically the mother-in-law is marriageable in many systems,' says Mr. Crawley, 'and so there would be no incest…' But Mr. Atkinson is not contemplating the danger of incest as the cause of mother-in-law avoidance; his theory postulates jealousy – that of the mother-in-law's husband, and, for what it is worth, that of the mother-in-law's daughter. Mr. Crawley's objection, I think, does not invalidate Mr. Atkinson's theory; especially as he does not reflect that the possible mother-in-law may have a caprice for her son-in-law, while the would-be son-in-law, less frequently, may follow the course of Colonel Henry Esmond.

2. Sir John Lubbock's (Lord Avebury's) theory, of enmity caused by capture, Mr. Atkinson has dealt with; it is rejected by Mr. Crawley.

3. Mr. Tylor's theory (Journal Anthrop. Institute, xviii. 247), is that of 'cutting' 'an outsider,' not one of the family, not recognised till his first child is born. For various reasons, Mr. Crawley rejects this explanation, rightly, I venture to think. Mr. Crawley holds that the mother-in-law avoidance 'seems to be causally connected with a man's avoidance of his own wife,' which he regards as only one aspect of the tabu between the two sexes, superstitiously regarded as dangerous to each other. But, like Mr. Atkinson, I much doubt whether the 'avoidance,' as far as it goes, of husband and wife is, in the main, the result of this superstition, though it plays its part on special occasions, as before the women sow the crops, and before the men go forth to war. Mr. Crawley's suggestion that, as husband and wife are perpetually breaking the alleged sexual tabu, the mother-in-law becomes 'a substitute to receive the onus of tabu,' 'a good instance of savage make-believe' does not carry conviction. Mr. Atkinson's theory seems 'as good as a better' (Mystic Rose, pp. 400-414). – A. L.

CHAPTER VIII

THE CLASSIFICATORY SYSTEM

The classificatory system. – The author's theory is the opposite of Mr. Morgan's, of original brother and sister marriage. – That theory is based on Malayan terms of relationship. – Nephew, niece, and cousin, all named 'sons and daughters.' – This fact of nomenclature used as an argument for promiscuity. – The author's theory. – The names for relationship given as regards the group, not the individual. – The names and rules evolved in the respective interests of three generations. – They apply to food as well as to marriage. – Each generation is a strictly defined class. – Terms for relationship indicate, not kinship, but relative seniority and rights in relation to the group. – The distinction of age in generations breaks down in practice. – Methods of bilking the letter of the law. – Communal marriage. – Outside suitors and cousinage. – The fact of cousinage unperceived and unnamed. – Cousins are still called brothers and sisters; thus, when a man styles his sister's son his son, the fact does not prove, as in Mr. Morgan's theory, that his sister is his wife. – Terms of address between brothers and sisters. – And between members of the same and of different phratries. – These corroborate the author's theory. – Distinction as to sexual rights yields the classificatory system. – Progress outran recognition and verbal expression. – Errors of Mr. Morgan and Mr. McLennan. – Conclusion. – Note. – ' 'Group marriage.'

In the gradual evolution of the group into the tribe during the long period of transition, the modifications in the internal organisation, which took place as the necessary result in the march in progress, should have left traces which we may also be able to follow in living custom. The immigration of the outside suitor, in its synchronism with the decay of paternal incest, must have entailed continual complications demanding regulation, and the resolution of each problem would lead to an almost mechanical step in advance. When by force of circumstances of environment or others such a step became retrograde, then we may expect an aberrant form whose very anomalism should lead to a facile recognition, and prove equally fertile in interpretation. Indeed, a curious vestige of the effect in action of the habit of incest, when brought into inevitable contact with progressive social evolution, is to be discerned in the nomenclature of that earliest phase of the classificatory system which Mr. L. H. Morgan has called the Malayan. From the general prevalence among lower races of a division into classes by generations of the members of group, and the deduction we see drawn in Ancient Society from the Hawaiian terms of relationship therein detailed, as to a previous state of general promiscuity, it will be desirable thoroughly to examine the whole question of the so-called classificatory system. It is doubly imperative in view of our own hypothesis, which, as regards the primary origin of society, may be said to be exactly the reverse of that of Mr. Morgan, in as far as the sexual inter-relations of brother and sister are concerned.

We have tried to portray the imperative evolution of a primal law as the sole possible condition of the first steps in social progress, a law which had so specially in view the bar to sexual intercourse between a brother and sister that it might, if a name for it were needed, be called the anadelphogamous law. [Mr. Atkinson wrote 'asororogamic,' which is really too impossible a word for even science to employ.] Mr. Morgan, on the contrary, says,316 'The primitive or consanguine family was founded upon the inter-marriage of brothers and sisters own and collateral in a group.' He adds,317 'The Malayan system defines the relationship that would exist in a consanguine family, and it demands the existence of such a family to account for its own existence.' And again,318 'It is impossible to explain the system as a natural growth, upon any other hypothesis than the one named, since this form of marriage alone can furnish a key to its interpretation.' He bases his argument on the fact that319 'under the Malayan system all consanguines, near and remote, fall within some one of the following relationships, viz. parent, child, grandparent, grandchild, brother and sister – no other blood relationships are recognised,' and says, speaking of promiscuity, that320 'a man calls his brother's son, his son, because his brother's wife is his wife as well as his brother's, and his sister's son is also his son because his sister is his wife.'

Now that a brother's son should be called a son is quite simple, as being a natural effect of the group marriage of brothers, the prevalence of which as a habit, and its effects, MM. Lorimer and Fison so well show among the Australians.321 But that a sister's son should also be termed, by her brother, a 'son' is certainly a very different thing indeed, despite Mr. McLennan's and other arguments to the contrary. In this verbal detail lies the whole crux of the matter as regards Mr. Morgan. That it should have given rise to such diversity of opinion and suggested his theory of brother and sister marriage need hardly be matter of surprise. For it is at once, evident that a group holding such nomenclature ignored cousinship, even if it existed. To all later seeming my sister's son must be nephew to ego quite necessarily. That at any stage he should be unrecognised as such seems the more astonishing, as even in the very early times when totems first arose, and arose probably and precisely to distinguish cousins as such,322 each cousin is of a different totem to the other, and thus not only eligible in marriage with another cousin, but in many lower races the born spouse each of the other. The whole question thus resolves itself into the exact value of the term we find used in the Hawaiian designation of the sister's son by her brother. Now it is important to note that two causes might have for effect the form of nomenclature in which a brother and sister each call the child a son, and thus ignore a possible cousinship. One cause is that some factor in self-interest or otherwise allowed such relationship to remain unrecognised, although existent, and another is that, as cousinship did not exist at all, there could be no recognition, or, as Mr. Morgan puts it, 'his sister's son is also his son because his sister is his wife.' To determine which is correct certainly seems difficult, and the whole thing has evidently been considered a most stubborn fact for the opponents of promiscuity.

That Mr. Morgan should have seized it in support of his theory, and that the theory should be so largely accepted, is not astonishing. Happily the great value of his ensuing argument as regards tribal development is in no way impaired if it can be shown, as we hope to do, that there is no necessity for an hypothesis of promiscuity to explain the terms in the Malayan table, which apparent need seems primarily to have led Mr. Morgan to evolve the idea of his primitive group. In fact, it becomes evident that, if we can furnish a clue as to how a sister's son came also to be a brother's son, without having recourse to the theory of an incestuous union of brothers and sisters, we at least discount the need of Mr. Morgan's 'consanguine family,' in which such incest is supposed to be a most characteristic and essential feature. We hope to prove that the terms which misled him are more apparent than real as proofs of any real affinity in blood, and that the original conception in causal connection was something quite apart.

Sir John Lubbock (Lord Avebury) has observed that the lower the milieu of a social status the less we see of the individual and the more of the group. In the case before us the individual as such does not exist at all, and there is only question of the group in its relation to its component classes. To confound one with the other led to Mr. Morgan's error.

There was much, in fact, in Mr. McLennan's shrewd remark in criticism of Mr. Morgan's theory that he did not seek the origin of the system of nomenclature in the origin of the classification of the connected persons, and that he courted failure in attempting to solve the problem by explaining the relationships comprised in the system in detail.'323 But it seems to me that Mr. McLennan fell into the same error when he contented himself with the misleading analogies which a comparison with the Nair family system presented. These, however striking, are, as we shall find, simply the result of the fact that class or communal marriage was the common trait of the polyandrous and the Cyclopean family, nor can I see that Mr. McLennan followed his own excellent advice as regards the possible identity in origin of nomenclature and classification; if he had so done, his acute mind could not have failed in a resolution of the whole problem, whereas his final resume of the argument is in terms which I profess to be quite unable to grasp.

Before entering into the matter ourselves, we must keep in mind our affirmation as to the axiom which must, in my opinion, guide us in all research into the hidden causes of early social evolution. All innovations, as we have said, in the regulation of society, all novel legislative procedure so to speak, will be found to have relation to the sexual feelings in jealousy. This already is the genesis of the primal law, and, in each case of avoidance, we have found jealousy the leading factor. It is the same in the case before us. Bearing this in mind, let us then follow Mr. McLennan's advice as to seeking the origin of the classification of connected persons. Now what would be the family economy of the primitive group, and who are its component individuals, whose interests, in sexual matters, are likely to clash, and whose mutual relationship in this respect demanded distinction in furtherance of regulation of their respective rights?

The original primitive type of family, which we have called 'the Cyclopean,' has disappeared, giving place to a higher form, which, by the inclusion of male offspring, has permitted the existence of several generations in presence. The component individuals, speaking of one sex only, would be old males, males, and young males representing three generations. It is the interests of these generations, which, in sexual matters and in choice of food, &c. would be likely to clash, for we may be sure that the seniors, as with actual savages, would desire the lion's share. Distinction then being necessary, it would naturally, as with individuals, be based on relativity of age, seniority within certain limits confering priority. Thus gradually each generation, as indeed with actual lower races, would, qua generation, come to be a distinctly defined class with certain separate rights and obligations. In this simple necessity of a classification of the connected persons, we see the origin of the classificatory system itself, as an institution. Divers interests, as between seniors and juniors, demanded strict demarcation, and the limits of a generation furnished the required lines to mark them.

The very natural distinction by relativity of age was simply, as with individuals, utilised as the requisite machinery in regulation of mutual rights of the individual himself. His rights are a matter of concern simply within his generation, in which the relation is purely paternal and communal, with the sole reservation of rights conferred by seniority.

Even when later denominative expression was given to the idea of a generation, terms almost identical of male, old male, and young male are used, as there is no desire to convey any idea of personal kinship, and there is merely in view reference to relativity of age of a class in relation to the group. Later, as Mr. McLennan says (p. 277): 'Whatever class names primitively signified, Kiki would come to mean child, Kina parent, Moopuna grandchild, Kapuna grandparent, but originally no such idea of kinship was in view.' The classificatory system evolved itself simply as the result of a desire to define certain rights, and the division by generations was the most natural and feasible for the purpose. But the very simplicity and paucity of the original terms show that it was applied to any simple group form. In fact, we are here dealing with that primitive form which bound people together, by the mere tie of residence and locality, and was purely exogamous in habit. Now when we consider that this fixed relativity of age by generation was originally evolved in view of the relations within such a family, we can imagine that complications might arise from such arbitrary definitions, when, later, this family expanded into the numerically large tribe composed of two intermarrying totem clan groups [phratries].

Primitively, doubtless, as between the classes, the genetic idea as regards sexual matters was (as still with savages in questions of food) to favour the seniors and defend their rights in defining each one's status. But actually, with the decay of incest, it would become what it is as among lower races, where nothing is more remarkable than the strict interdict upon any union between members of different generations.324

It is evident that hence complications might arise perplexing to the savage mind. For instance, we may expect to find cases where the niece is an adult, whilst the aunt is still an infant, and yet marriage between the former and the son of the latter is obligatory, as they are cousins of the same generation. Here, probably, we have a clue to one of the most bizarre facts in anthropology, where the universal rule as to sexual connection between generations seems to be wantonly disobeyed, although in reality the reverse may be seen to be the case on examination. It is recorded of the Keddies of Southern India that a very singular custom exists among them, a young woman of sixteen or twenty years of age may be married to a boy of five or six years. She, however, lives with some other adult male (perhaps a maternal uncle or cousin), but is also allowed to form a connection with the father's relatives, occasionally it may be the boy's father himself, i.e. the woman's father-in-law! Should there be children from these liaisons, they are fathered on the boy husband. When the boy grows, the wife is either old or past child-bearing, when he in turn takes some other boy's wife in a manner precisely similar to that in his own case and procreates children for the boy husband.

By the classificatory system, as each in fact is a member of the same generation, they are born husbands and wives. The enforced virginity of the wife, implied under such conditions, entailed a celibacy incompatible with all lower ideas. It is easy to imagine the compromise between his conscience and his desires which a savage would make in such a case when favoured (or forced) by circumstances of environment, for it is unknown elsewhere. The infant nephew goes through the ceremony of marriage, which, by a fiction, being thus legally consummated, the wife is left free to follow her desires. These, however, are by no means allowed to run riot. They are regulated in a fashion of which, although the peculiarity is noted by the authors of the extract, the full significance can only be appreciated in connection with our hypothesis. She formed indeed connections outside of her husband, but solely with those of the legally eligible totem. As I believe the Keddies have male descent, these would be sons of the father's sister, or sons of the mother's brother, or again with the latter himself, who was her father-in-law, whereas union with the sons of the father's brothers, or of the mother's sisters, as being of the same totem, would not take place – and this we find to be the actual fact, as evidence proves.

But still other complications will be found to arise as the effect of the original concept of the classificatory system when brought face to face with new and advanced social order, which will have closer relation to our present argument. The distinctive feature in the economy of the primitive group in its relation to all other groups was mutual hostility. The instinctive distrust of strangers would be accentuated by the habitual hostile capture of females, for such groups, except in the case of the incest between father and daughter, were yet purely exogamous. But such mutual hostility implies isolation of each community. Thus all law evolved, as we have said, would be purely with a view to regulation of the internal economy of a single consanguine group alone. Now in such a group, the division into generations of old male, male, and young male implied (although not as yet understood as between generations) the relationship of parents and children. Each generation is either child or parent to the other. As marriage is communal,325 all the fathers in one generation are fathers to all the children in the next indiscriminately, and conversely these children recognise as fathers all the males of the senior generation. It follows that the relationship of all the members of a generation is purely fraternal, all are brothers and sisters to each other, and in this consanguine family they were really either actually so, or at least half brothers and half sisters.