полная версия

полная версияA History of Lancashire

In Middleton Church there was a brass to the memory of Sir Ralph Assheton and his bowmen, and a painted window still remains to commemorate the event. Of the general state of some of the larger towns of the county, we have a brief record from the pen of that careful antiquary John Leland, who went through Lancashire in 1533. Manchester he says was “the fairest, best built, quickest [i. e., liveliest] and most populous town in Lancashire; well set a worke in makinge of clothes as well of lynnen as of woollen, whereby they have obtained, gotten and come vnto riches and welthy lyuings, and have kepte and set manye artificers and poor folkes to work;” and in “consequence of their honesty and true dealing, many strangers, as wel of Ireland as of other places within this realme, have resorted to the said towne with lynnen yarne, woollen, and other wares for makinge clothes.” So great a name had Manchester now got for the making of woollen cloth that in an Act passed in 1552 Manchester “rugs and frizes” are specially named; and in 1566 it became necessary to pass another Act to regulate the fees of the queen’s aulneger (measurer), who was to have his deputies at Bolton, Blackburn and Bury. The duty of these officers was to prevent “cottons, frizes and rugs” being sold unsealed. Cottons were not what is now meant by this term, but were all of woollen.107 Cotton manufacture did not begin until a century later. Manchester at this time probably consisted of some ten or a dozen narrow streets108 and lanes, all radiating from the old church; its water was from a single spring rising in what is now Fountain Street, and which flowed down Market Street to Smithy Door. The town business was conducted in a building called the “Booths,” where the court of the lord of the manor was held, and near to which stood the stocks, the pillory and whipping–post, and not far distant was the cucking–stool pool. These streets were narrow, ill–paved, or not paved at all; the houses were of wood and plaster, with the upper stories projecting and mostly roofed with thatching. The only church in Manchester was the collegiate or parish church, which stood on the site of the present cathedral in the time of Edward VI.; the lord of the manor of Manchester was Sir Thomas West, Knight, ninth Baron de la Ware. The early records of the Manchester court leet109 have been preserved, and furnish some interesting details of the life of the dwellers in the town at this period.

In 1522, amongst the officers of the court, were two ale–founders (or, as they are generally called, ale–tasters or conners), two byrlamen (lawmen) to overlook the “market stede,” two for Deynsgate and four for the mylne gate, wething greve, hengynge dyche, fenell street, and on to Irkes brydge, and a score of people were named as “skevengers,” whose duty it was to see that the streets were kept clean. At the same court an order was made that persons were not to allow their ducks and geese to wander into the market–place, and certain other regulations were enforced, showing that even at that date the sanitary arrangements of the place were to some extent attended to.

In 1554 we have, beside the other officers, market overlookers for fish and flesh, leathersellers, and men to see that no ox, cow, nor horse goes through the churchyard; and it was ordered that all the middens standing in the streets, between the conduit (which supplied the town with water) and the market–cross, and all swinecotes in the High Street, should be removed. The authorities appear to have had some trouble to persuade the people that the street, or the front of their own houses, was not the place for dunghills or middens, as the orders to remove them appear at almost every court, in some cases the order only being to erect a pale or hedge round, so that there be no “noyance nor evil sight in the street.”

In 1556 warning was to be given in the church that the inhabitants were to bring their corn and grain to be ground at the Free School Mill.

Ale and bread in 1558 were to be sold only by the regulation measures and weights. Archery had long been one of the recreations of the people, so we are surprised to find that in 1560 the inhabitants were ordered to have put up before the Feast of St. John the Baptist (June 24) a pair of butts in Marketstede Lane, and another pair upon Colyhurst Common; in the same year it was ordered that no person should allow any carding or bowling in his house or garden, fields or shop, “whereto any poore or handiecrafts men shall come or resort.”

Provisions were also made for the traveller whose business brought him to Manchester, for no man was allowed (in 1560) to brew or sell ale unless he was able to “make two honest beddis [beds],” and he was also to “put furth the syne of a hand.” Later on it was ordered that this sign was only to be used when the innkeeper had ale to sell. It is curious to find an old Act passed in 1390 still enforced, viz., that no one not being a forty–shilling freeholder shall keep a greyhound nor any hound.

Ale was not to be sold to be drunk on the premises at more than 6d. a gallon; for outdoor consumption the price was not to exceed 4d. a gallon.

A singular order appears in the next year’s record, to the effect that no one shall sell bread which has any butter in it, although he was permitted to bake it for his own use or to give to his friends.

About this time it appears to have been the custom at weddings and other festive occasions to invite people to the feast – which was held at an alehouse – and then collect from them a sum of money to defray the expenses, and to stop this practice the court ordered that no one should be called upon to pay more than 4d. for such entertainment.

No doubt the fairs of Manchester were now resorted to by considerable numbers, hence the order made in 1565 that every burgess was to find an able–bodied man, furnished with a bill (or axe) or a halberd, to wait upon the steward of the manor at these gatherings. At this time fruits, particularly apples, were sufficiently an article of commerce as to necessitate the appointment an overseer to regulate their sale. The manufacturers of “rugs” (a kind of coarse woollen cloth) were now forbidden to wet their good “openly in the stretes,” but to do it either within their respective houses or behind the same.

Alehouses were frequently the subject of the court’s regulation, gaming, selling of ale during “tyme of morning prayer,” and the like offences being severely dealt with, whilst drunken men found abroad in the streets at night were not only imprisoned in the “dungeon,” but had to pay 6d. to the constable for the poor, and the unfortunate ale–house keeper, if found in a state of intoxication, was “discharged from ale–house keeping.”

The wearing of daggers and other weapons was found to lead to disorder, and forbidden, and the law forbidding the wearing of hats110 on Sundays and holidays was enforced. Apprentices and male and female servants were to be fined if found in the streets after nine o’clock at night in the summer and eight o’clock in the winter.

The practice of archery towards the end of the century began to fall off, and notwithstanding the Acts of Parliament passed to encourage it here in Manchester, officers had to be appointed to see the burgesses “exceryse [exercise] shootinge accordinge to the statute.”

Although Manchester was not at the time a borough, yet it is evident that the court leet was alive to many of the requirements of a growing town, and that, although its industries were now only in infancy, it had become a commercial centre, and was beginning to emerge from the obscurity to which it had been relegated during the feudal system.

The plague of 1565 was succeeded in the year following by a great dearth, when a penny white loaf only weighed 6 or 8 ounces.

Even at this date the Manchester church was often selected as the place to be married at, although neither the bride nor the bridegroom lived in the town, and on these occasions they were accompanied by “strange pipers or other minstrels,” who played up to the church doors and after the ceremony at the ale–house. This raised the jealousy of the “town waytes,” who persuaded the court to order that they should come no more.

After Manchester, the next largest town was Preston, which was the capital of the duchy and one of the oldest incorporated towns in the county. Before the time of Elizabeth it had had no less than ten royal charters, and within it were two religious houses and its very ancient parish church; moreover, its “guild merchant” had been held every twentieth year for centuries. The guild roll of 1542 contains the names of over 200 burgesses, that of 1562 exceeds 350, and the one of 1602 gives 537 in burgesses, and 561 foreign or out burgesses. In the lists for 1562 and 1582 we find enumerated drapers, pewterers, cordwainers, glovers, masons, websters (weavers), tailors, mercers, butchers, carpenters, barbers, tanners, saddlers, flaxmen, leadbeaters, cutlers, schoolmasters, and other occupations which accompanied a well–to–do town of this period. The sale of woollen cloth and fustians was at this time a branch of Preston trade. Here also strict regulations were enforced as to the accommodation at inns, no one being allowed to retail ale unless he could lodge four men and find stabling for four horses. It was such regulations as these that enabled Holinshead (in 1577) to record that “the inns in Lancaster, Preston, Wigan and Warrington” are so much improved “that each comer” is “sure to lie in clean sheets wherein no man hath lodged; if the traveller be on horseback his bed–cloth cost him nothing, but if he go on foot he hath a penny to pay.” Preston was one of the four Lancashire towns which in 1547 recommenced to send members to Parliament. Toward the end of the sixteenth century Preston had a population of something like 3,000.

The chief town of the county for many centuries was Lancaster, though in size and importance it had now been excelled by several other towns. The old castle was the county gaol, and in this town until quite recently the assizes were held, and, moreover, it was the oldest corporate borough, dating back to the twelfth century; yet for all this, in an Act of Parliament passed in 1544, it is reported as to Lancaster that though there were many “beautiful houses” there, they were all “falling into ruin,” and in 1586 Camden reported that “it was thinly peopled and all the inhabitants farmers, the country round it being cultivated, open, flourishing, and not bare of wood.” As a town it consisted of only eight or nine streets, but there was a school, fishmarket, pinfold, etc.111 Lancaster returned two members in 1529, and from 1547 continued to send that number.

Liverpool in the time of Henry VII. had begun to fall off in importance, and we find that that monarch made a grant of the “Town and Lordship of Litherpoole” at a rental of £14 a year; this was renewed in 1528.

Henry VIII., always on the look–out for royal revenues, ordered in 1533 a return to be made of the King’s rental in Liverpool, when it was found only to amount to £10 1s. 4d., a sum equal to something like £150 of the present money;112 this was exclusive of Church property. The streets of Liverpool were Water Street, Castle Street, Dale Street, Moore Street, Chapel Street, Jugler Street and Mylne Street. The Act of Parliament of 1544 reports of Liverpool as it had done of Lancaster (p. 97), both towns being put down as having fallen into decay; and yet both towns in 1547 returned two representatives to Parliament. Why had these two ancient boroughs so decayed? One reason probably, in the case of Liverpool, was its comparative isolation, as until centuries after this there was no road to it for wheeled carriages, all inland travellers having to go on horseback, and goods on packhorses, or by barges on the Mersey, from Warrington.

All these ancient boroughs, provided they paid the dues to the national exchequer, and to some extent carried out the statutes of the realm, were at liberty to make their own laws for self–government, and it is but natural to suppose that this arbitrary rule in some cases resulted in success, whilst in others it led to results disastrous to the community. Again, the visitations of the plague in some towns carried away a large percentage of the population, whilst in others their effects were slight. Either or both of these causes would be sufficient to materially reduce the prosperity of one of these small boroughs. In 1540 Liverpool is said to have been nearly depopulated by the plague; and in 1556 there were only 151 householders left, which could not represent a population of much over 1,000;113 and in 1558 the visitation of this scourge was so severe that all who were attacked were ordered “to make their cabins on the heath,” and to remain there for nearly three months, and after that (until they had permission to do otherwise) to keep on “the back side of their houses, and to keep their doors and windows shut on the street side.” This plague carried off upwards of 240 of the already reduced inhabitants. At this time we find warehouses for merchants named, and the Corporation had a ferry boat to carry people and goods across the river. The port of Liverpool was now claimed to be a dependency of the port of Chester, and so indignant were the Corporation at this that they sent their Mayor to London to represent to the Chancellor of the duchy that to call Liverpool “the creeke of Chester” was not only to punish its inhabitants, but was against the jurisdiction and regal authority of the county palatine and duchy; and they also stated that Liverpool had heretofore been reputed the best port and harbour from Milford to Scotland, and had always proved so with all manner of ships and barks. From the return made in consequence of this appeal, it appears that Liverpool had only twelve vessels, the largest of forty tons burden.

The close of the sixteenth century did not find the town in a much better position, for even the keeper of the “Common Warehouse of the Town” was only to have £1 2s. 8d. for his wages, because of “the small trade and trafique” that there then was, and a pious ejaculation is added, “until God send us better traffique.” The principal trade now carried on was with Ireland and Spain or Portugal; to the latter herrings and salmon were exported and wine brought back. Wool, coatings (cottons), and tallow were exported in small quantities. Many regulations referring to the sanitary arrangements of the town and the suppression of drunkenness and gaming were almost identical with those enforced by the court–leet of Manchester. A “handsome cockpit” was made by the Corporation in 1567, and horse–racing was patronized ten years later.

The only other town in Lancashire which in 1547 returned representatives to Parliament was Wigan.

Leland, who paid a visit to Wigan about the year 1540, thus describes the town: “Wigan pavid as bigge as Warington and better buildid. There is one paroch chirch amidde the Towne, summe Marchauntes, sum Artificers, sum Fermers. Mr. Bradeshaw hath a place called Hawe a myle from Wigan; he hath founde moche Canel like se Coole in his ground very profitable to hym.” The vast underground wealth, which was in the future to be of such importance to this county, would appear at this time to be unworked, if even its existence was known. Wigan was one of the few towns in the county with its Mayor and Corporation. The population of Wigan would scarcely be as great as Warrington (which was now about 2,000114), as in 1625 the number of burgesses entitled to vote at the election was only 138. Warrington was not incorporated, but was under the manor court. Its chief industry was the manufacture of sail–cloth. Clitheroe, though a borough, was still (except for its connection with the castle) a place of small importance, as was also Blackburn; at neither place had as yet any textile industry been introduced. At Bolton–le–Moors Leland found cottons and coarse yarns manufactured, and here also they were accustomed to use “se cole, of which the pittes be not far off.” At Bury also yarns were made.

Rochdale was “a market of no small resort,” says Leland, but he is silent as to its commercial doings; nevertheless, if manufacture was not carried on there, its inhabitants were doing a good business in the sale of wool and coatings, as is proved by the fact that several cases of dispute as to the non–delivery of goods of this kind were heard in the duchy court. In the reign of Elizabeth the manufacture of these articles soon followed, and before the end of the century this industry was well established here. Some of the coal in this district lying near the surface was now worked, and cutlery was also made in this wide parish, as were also hats. Foot–racing was a favourite pastime in Lancashire in the sixteenth century, and sometimes the stakes ran high, as in the case of a race run near Whitworth (Rochdale) on August 24, 1576, when the match was for twenty nobles a side.115

Before the introduction of the woollen and cotton manufacture, and the consequent rapid increase of population and buildings, this county was very far from being amongst the least beautiful of England’s shires. Large unbroken forests, where still lingered the lordly stag, surrounded with game of varied kinds, were yet to be seen; and the dense smoke from the tall factory chimney was not there to blast and wither with its poisonous breath the tender foliage of the stripling oak. Its rivers then meandered through miles of pleasant lands, where the lowing of cattle and the melodious songs of birds formed the only accompaniment to the gentle rippling of the waters; no contaminating dyeworks, chemical works, or other followers in the train of commerce, had yet planted themselves along the banks; and the salmon, the grayling and the trout, and other small fry, held undisputed possession, unless they were molested by the otters, which were then abundant.116 In the northern parts of the county things still remained much as they had been for centuries, except, of course, in some districts a slight increase in population, and in all an improved state of civilization and culture. Amongst these towns in the north may be mentioned Kirkham, which claims to have been incorporated in the time of Edward I., by the name of “the bailiffs and burgesses.” This claim was ratified by James I. They had a market and fair, but did not send representatives to Parliament.

In the days when the monasteries and abbeys were young, no doubt the education of the people was one of their recognised duties, but when these religious houses became (as they often did) the homes of luxury and licence, this duty was unfulfilled; and it was only after the Reformation, when the religious excitement abated, that anything like an attempt at national education was made, and at this time schools of any kind were almost unknown in the county, and the mass of the people were alike ignorant, untaught, and superstitious.

Preston was probably the first town in Lancashire which had a free school regularly endowed; it is said to have been established in the fourteenth century, but was certainly there in the time of Henry VI., as in 1554 a plaintiff in the duchy court spoke of it as having then been in existence for “the space of 100 years,”117 and the incumbent of the chantry in the parish church, founded by Helen Houghton (about 1480), was required to “be sufficiently lerned in grammar” to teach the scholars. Manchester was indebted to Hugh Oldham, the Bishop of Exeter (a native of Lancashire), for its first free school. In 1515 the Bishop conveyed certain lands to the Wardens of Manchester for the purpose of paying a master and usher to teach the youth of the district, who had, as the indenture sets forth, “for a long time been in want of instruction, as well on account of the poverty of their parents as for want of some person who should instruct them in learning and virtue.” Before his death, in 1519, he had built the school which has for so long done honour to its founder.

At Kirkham a free grammar school had been, or was just about to be, founded in 1551, when Thomas Clifton, of Clifton, bequeathed “towards the grammar schole xxˢ.” And in 1585 the parish authorities took possession of the school–house in right of the whole parish. This school appears subsequently to have fallen into decay or been given up, for in 1621 Isabel Birley, who had been all her life an alehouse–keeper in Kirkham, being “moved to compassion with pore children shee saw often in that town,” went to the church (where the thirty sworn men were assembled) with £30 in her apron, which she wished to give for the building of a free school; her example fired the others with enthusiasm, and the requisite sum was soon raised. The history of this well–known school is interesting.

When Queen Elizabeth ascended the throne, besides these schools there were free grammar schools at Prescot, Lancaster, Whalley, Clitheroe, Bolton, and Liverpool, but within the next fifty years many more were added, amongst them being those at Burnley, Hawkshead, Leyland, Rochdale, Middleton, and Rivington (near Bolton). To most of these early–founded schools libraries were attached, in some of which still remain many valuable sixteenth–century books.

The belief in witchcraft and its kindred superstitions was firmly rooted amongst the people; on this subject something will be said in another chapter, but en passant it may be stated that in 1597 a pardon was granted to one Alice Brerley, of Castleton (in Rochdale), who had been condemned to death for slaying by means of witchcraft James Kershaw and Robert Scholefield.118

The condition into which Lancashire was thrown through the religious crisis consequent upon the Reformation will be treated of elsewhere, but it must here be noted that in the time of good Queen Bess churches were said to be almost emptied of their congregations, alehouses were innumerable, wakes, ales, rushbearing, bearbaits, and the like, were all exercised on the Sunday, and altogether a general lawlessness appears to have prevailed all over the county. In the reign of Henry VIII. the old commissions of array (whose duty it was to get together in each county such armed forces as were required from time to time) were done away with, and their places occupied by lord–lieutenants.

In 1547 the Earl of Shrewsbury was Lord–Lieutenant of the county of Lancaster and six other counties, but in 1569 the county had a Lord–Lieutenant of its own in the person of Earl Stanley, third Earl of Derby. The duties of these newly appointed officers of the Crown were manifold; but one of their chief services was to assemble and levy the inhabitants within their jurisdiction in the time of war, and to prescribe orders for the government of their counties; and from the proceedings of the Lancashire lieutenancy we may glean a few details relating to the civil and religious life of the period.119 For the military muster of 1553 the quota required from the respective hundreds was: West Derby 430, Salford 350, Leyland 170, Amounderness 300, Blackburn 400, Lonsdale 350.

These numbers were to be raised by each town in the hundred in proportion to the wealth or number of its inhabitants: West Derby, Wigan, and Ashton, in the parish of Winwick, had to find 11 each, whilst Liverpool only sent 5. In Leyland the greatest number (10) came from Wrightington with Parbold; in Amounderness Preston found 26, whilst the parish of Kirkham contributed over 100. Blackburn parish sent 113 men, and the parish of Whalley 175; unfortunately, the particulars for the towns and parishes of Salford are wanting. In 1559–60 the county was called upon to raise no less than 3,992 soldiers.

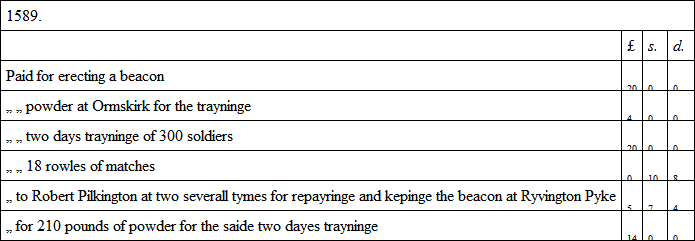

During all these troubled times the highest hills in the district were used as beacon stations, where a system of signalling was practised; thus, in 1588 the hundred of Salford was called upon to pay £5 9s. 4d. for watching the beacon on Rivington Pike from July 10 to September 30.

Some further details about this particular are furnished in the original “accompt” of Sir John Byron, who was a Deputy–Lieutenant of the county:

Notwithstanding the wars and rumours of wars which were then so common, and notwithstanding the religious excitement created by the persecution, first of the Roman Catholics and then of the Puritans, people seem to have prospered in the county. The towns and villages greatly increased in number, size and importance, and the time of Elizabeth especially witnessed the erection and rebuilding of some of Lancashire’s finest halls. The ancient domestic houses which had been the residences of the old feudal lords were now remodelled or entirely swept away, and the subdivision of the land brought out a new class of proprietors, who, though not descended directly from the old owners of the soil, soon took up the rank of gentry, and built for themselves those smaller though not less interesting mansions which at one time were found all over the county.