полная версия

полная версияA History of Lancashire

In the case of the transfer of the honour of Lancaster to Edmund Crouchback, it appears that the King had previously granted the custody of the county of Lancaster to Roger de Lancaster, to whom, therefore, letters patent were addressed, promising to indemnify him.68

The close of the twelfth and the beginning of the thirteenth century witnessed a considerable increase in the population of the county, and the consequent advance in the importance of its now growing towns. Lancaster in 1199 had become a borough, having granted to it the same liberties as the burgesses of Northampton. Preston, a little before this, had been by royal charter created a free borough, in which the burgesses were empowered to have a free guild merchant, and exemption from tolls, together with many other privileges that King John confirmed in 1199, and granting the additional right to hold a fair of eight days’ duration. Cartmel is reputed to have had its market before the time of Richard I. (A.D. 1189–1199). King John in 1205 granted to Roger de Lacy the right to hold a fair at Clitheroe,69 and also, in 1207, gave to the burgesses in the town of Liverpool all the liberties and customs usually enjoyed by free boroughs on the sea–coast. Henry III. granted further charters to both Preston and Liverpool in 1227.

In or about the year 1230, Randle de Blundeville, Earl of Chester and Lincoln, granted that the town of Salford should be a free borough, and that the burgesses, amongst other privileges, should each have an acre of land to his burgage, the rent for which was to be 3d. at Christmas, and a like sum at Mid–Lent, the Feast of St. John Baptist and the Feast of St. Michael. The barony of Manchester was at this time in the hands of the Greslet family, one of whom, in 1301, gave a somewhat similar grant to Manchester, save that the clause providing the acre of land was omitted. From these two charters several items may be extracted, as showing the position of burgesses in those days, and their relation to the lord of the barony or manor. At Salford, no burgess was to bake bread for sale except at the oven provided by the lord, and a certain proportion of his corn was to be ground at the manorial mill. The burgesses were to have common free pasture in wood or plain, in all pasture belonging to the town of Salford, and not be liable to pay pannage;70 they were also allowed to cut and use timber for building and burning.

A burgess dying was at liberty to leave his burgage and chattels to whomsoever he pleased, reserving to the lord the customary fee of 4d. On the death of a burgess, his heir was to find the lord a sword, or a bow, or a spear.

The burgesses of Manchester were to pay 12d. a year in lieu of all service. In both charters power is given to the burgesses to elect a reeve from amongst themselves. The social difference between the free burgess and the villein is pointedly referred to in a clause which provides that “if any villein shall make claim of anything belonging to a burgess, he ought not to make answer to him unless he shall have the suit from burgesses or other lawful [or law worthy?] men.”

In Lonsdale, the monks of Furness obtained a charter dated July 20, 1246, authorizing the holding of an annual fair at Dalton, where a market had previously been established. Edmund de Lacy, in 25 Henry III. (A.D. 1240–41), obtained a royal charter for a market and fair at Rochdale, and a little later (in 1246) Wigan became a free borough, with right to hold a guild. Warrington,71 Ormskirk, Bolton–le–Moors, and Burnley, had each its established market before the close of the century; whilst on the north of the Ribble we find that Kirkham, which had as early as 54 Henry III. (1269–70) obtained a royal charter for both a fair and a market, was in 1296 made into a free borough with a free guild, the burgesses having the right to elect bailiffs, who were to be presented and sworn: this right subsequently fell into disuse. At Garstang, very early in the next century, the abbots of Cockersand were authorized to hold both a market and fair. Possibly some few other towns may have received similar privileges, and the record thereof been lost; but we have clear evidence that before the end of the reign of Edward I. (A.D. 1307) there were not far short of a score of Lancashire market towns, each of which doubtless formed the centre of a not inconsiderable number of inhabitants, some of whom were free men, whilst others were little better than villeins or serfs, their condition varying somewhat in the different manorial holdings into which the district was divided.

Churches and monasteries had sprung up (see Chap. IX.), and a few castles probably kept watch over the insecure places. The houses, such as they were, timber being plentiful, were built of wood; the occupation of the people was chiefly agricultural, and in the forests were fed large herds of swine, the flesh of which formed a large portion of the food of the inhabitants; but in each of the towns there were small traders and artisans, among whom, in many cases, were formed trade or craft guilds. The power of the great barons appears now to have become somewhat less, and the land through various processes began to be more divided, and we find in the owners of the newly acquired tenures the ancestors of the gentry and yeomen of a later date.

The forests of Lancashire at this date were of immense extent; they may be enumerated as these: Lonsdale, Wyresdale, Quernmore, Amounderness, Bleasdale, Fullwood, Blackburnshire, Pendle, Trawden, Accrington, and Rossendale. The law respecting forests dates back to Saxon times; Canute, whilst he was King, issued a Charter and Constitution of Forests. By this charter verderers were to be appointed in every province in the kingdom, and under these were other officers known as regarders and foresters.

If any freeman offered violence to one of the verderers he lost his freedom and all that he was possessed of, whilst for the same offence a villein had his right hand cut off, and for a second offence either a freeman or a villein was put to death. For chasing or killing any beast of the forest the penalties were at best very severe: the freeman for a first offence got off with a fine, but a bondsman was to lose his skin. Freemen were allowed to keep greyhounds, but unless they were kept at least ten miles from a royal forest their knees were to be cut.

King John, whilst Earl of Morton, held the prerogatives of the Lancashire forests, and he granted a charter (which, when he became King, he confirmed) to the knights and freeholders, whereby they were permitted to hunt and take foxes, hares and rabbits, and all kind of wild beasts except the stag, hind and roebuck, and wild hogs in all parts of his forests, beyond the demesne boundaries.

In the succeeding reign, however, the freemen were again troubled by the arbitrary and harsh treatment of the royal foresters, and in vain appealed to the King for relief. Edward I. to some extent relaxed the rigour of the laws, but still assizes of forests were regularly held at Lancaster, and presentments made for killing and taking deer, and the like offences, but the penalties were not nearly so severe as formerly.

Many cases might be quoted. At the forest assize at Lancaster on the Monday after Easter in 1286, Adam de Carlton, Roger the son of Roger of Midde Routhelyne, and Richard his brother, were charged with having killed three stags in the moss of Pelyn (Pilling in Garstang), which was part of the royal forest of Wyresdale.72 About the same date, Nicholas de Werdhyll having slain a fat buck in the forest of Rochdale,73 the keepers of the Earl of Lincoln’s forest came by night, seized him, and dragged him to Clitheroe Castle, where he was imprisoned until he paid a fine of four marks.74

Sometimes it was not the individual who was the offender, but the whole of the inhabitants. Thus, in 34 Edward III. (1360–61) a sum of 520 marks was levied upon the men and freeholders within the forest of Quernmore and the natives of Lonsdale, being their portion of a fine of £1,000 incurred for their trespass against the assize of the forest.75 No doubt this was a convenient way of raising money.

The number of writs of pardon for trespasses against the forest laws, which are still preserved amongst the duchy records belonging to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, suggest that the offender had to purchase his pardon. The religious men, as they were called, and the clergy often had granted to them the right to hunt in the forests, as well as other privileges. As an example of the latter may be named the grant made in 1271 by Edmund Crouchback to the Prior and monks of St. Mary’s of Lancaster, to the effect that they might for ever take from the forests in Lancaster,76 except in Wyresdale, two cartloads of dead wood for their fuel every day in the year, and have free ingress and egress into the forest with one cart for two horses, or with two carts for four horses, to seek for and carry such wood away. Gradually, as the population increased, and as the personal interest of the Dukes of Lancaster in the forests themselves became less, many of these old forest laws fell gradually into disuse; but as late as 1697 a royal warrant was issued to the foresters and other officers of the forests, parks, and chases of Lancashire, calling upon them to give annually an account of all the King’s deer within the same, and also to report how many were slain, by whom, and by whose authority.

The regulations as to fishing in the rivers of the county were not so comprehensive as the forest laws; but the value of various fisheries was fully recognised, and they became a source of revenue. In 1359 Adam de Skyllicorne had a six years’ lease of the fishing in the Ribble at Penwortham, with the demesne lands, for which he paid six marks a year, and in the succeeding year justices were assigned to inquire into the stoppages of the passages in the same river, by which the Duke’s fishery of Penwortham was destroyed and ships impeded on their way to the port of Preston. Fishing in the sea as a trade also met with encouragement, for in A.D. 1382 a precept was issued to the Sheriff to publish the King’s mandate, prohibiting any person in the duchy who held lands on the coast from preventing fishermen from setting their nets in the sea and catching fish for their livelihood; and in 13 Richard II. (1389–90) an Act was passed appointing a close time for salmon in the Lune, Wyre, Mersey and Ribble.

Notwithstanding that the fishing rights on both sides the Ribble had been leased or sold with the demesne lands, nearly 200 years later the King still claimed all manner of wrecks and fish royal which were cast upon the shore. On this point a suit in the duchy court appeared in 1536, in which the King’s bailiff charged one Christopher Bone with having taken away sturgeon and porpoises which had been washed ashore at Warton, in the parish of Kirkham, whereas they of right belonged to his Majesty.77 It may be noted that at this time the porpoise was considered “a dainty dish to set before the King.”

The Normans did not, as has been frequently stated, introduce that dreadful disease, leprosy, into England, as there were hospitals set apart for leprosy at Ripon, Exeter, and Colchester some time before their advent. In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries leprosy was very prevalent in the northern parts of Lancashire; and to meet the requirements a hospital was founded at Preston in the time of Henry III. How the lepers who were not in the hospitals were dealt with we have no evidence to show, but that they were harshly, not to say cruelly, treated, and were in a measure outcasts, may be safely assumed.

Shortly before April 10, A.D. 1220, Henry III. addressed a letter to Hubert de Burgh, instructing him to order the Sheriff and forester of Lancaster to desist from annoying the lepers there;78 and this not proving efficient, a royal writ was issued to the Sheriff (dated April 10) directing that officer to see that they were no longer molested by Roger Garnet and others, and that henceforth they were to have their beasts and herds in the forest without exaction of ox or cow, and also to be allowed to take wood for fuel and timber for building.

From this it appears clear that these lepers lived apart from the rest of the community, in houses or huts erected by themselves, and were not allowed to enter even a church; hence the use of what are known as leper windows, one of which still remains in the north chancel wall of Garstang Church. Leprosy continued with great severity for upwards of a couple of centuries, but towards the time of Henry VIII. it appears to have gradually decreased, and in the days of his immediate successor had almost died out.

The various Crusades of the twelfth century found many followers from Lancashire, and even when the Christians were fast losing their Asiatic possession it was thought worth while to appeal to this county for help, as we find, in June, 1291, the Archbishop of York instructing the Friars there to send three Friars to preach on behalf of the Crusades; one was to address the people at or near Lancaster, another at some place convenient for the Lonsdale inhabitants, and a third at Preston, in such a locality as it was believed the greatest congregation could be got together.79

The history of the wars between England and Scotland is a page of the general history, but it will be necessary here to state that in 1290 there were thirteen claimants to the Scottish crown, and this led to the beginning of the “Border warfare” between the people on the two sides of the Solway Firth, the Cheviots and the Tweed. Edward I., taking advantage of the position, put in a claim to the Scottish throne, and afterwards took possession as suzerain of the disputed feudal holding.

In 1292 Baliol was appointed King of Scotland with the consent of Edward I., to whom, however, homage had to be done, and out of this right of appeal, thus claimed by the King of England, arose that long series of wars between the two kingdoms which began in the early part of the year 1296, when Edward crossed the Tweed with an army of 12,000 men.

These wars were a great tax upon Lancashire, as, besides being subject to constant invasions, and bearing its share of the subsidies, from it were drawn from time to time large numbers of its bravest and best men. In 1297 Lancashire raised 3,000 men, and at the battle of Falkirk, in the vanguard, led by Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, there were 1,000 soldiers from this county. Another 1,000 foot soldiers were raised in 1306, and this constant drain continued for many years. After the battle of Bannockburn in 1314, the victorious Bruce besieged Carlisle, but after a long struggle he was obliged to retire, the commander of the castle, Sir Andrew de Harcla, as a recognition of his gallant services, receiving from the King the custody of Cumberland, Westmorland and Lancashire.80 Within a very few years, on a charge of treason, he was hung, drawn and quartered at Carlisle, one of the pleas raised against him being that he had allowed Bruce to pass into Cumberland and Lancashire, where his army had plundered and marauded in every direction; this was in July, 1322.

In the second half of this century we find several levies made upon Lancashire for soldiers to march against the Scots, but after this the county was not subjected to the frequent invasions with which its inhabitants had been too long familiar. The most serious of these invasions was the one in July, 1322, and of the effects of this and other raids we have an authentic record in the Nonarum Inquisitiones, taken (for North Lancashire) in 15 Edward III. (A.D. 1341). The commission appointed to levy this tax on the corn, wool, lambs, and other tithable commodities and glebe lands, were specially instructed to ascertain the value in 1292 (Pope Nicholas’ Taxation), and the then value, and where there was a material difference between the two, they were to ascertain the reason of such increase or decrease. They reported that at Lancaster much of the land was now sterile and uncultivated through the invasions of the Scots, that Ribchester and Preston had almost been destroyed by them, and that at the following places the value of the tithes was very seriously reduced through the same agency, viz., Cockerham, Halton, Tunstall, Melling, Tatham, Claughton, Walton, Whytington, Dalton, Ulverston, Aldingham, Urswick, Pennington, Cartmel, Kirkham, St. Michael’s–on–Wyre, Lytham, Garstang, Poulton, Ribchester and Chipping; except the two latter, all these are in Amounderness, and north of the Ribble; into none of the other parts of the county do the Scots appear to have penetrated. In some cases the reduction amounted to something like fifty per cent.; in fact, the invaders must have set fire to buildings and laid waste the land all along their line of march.

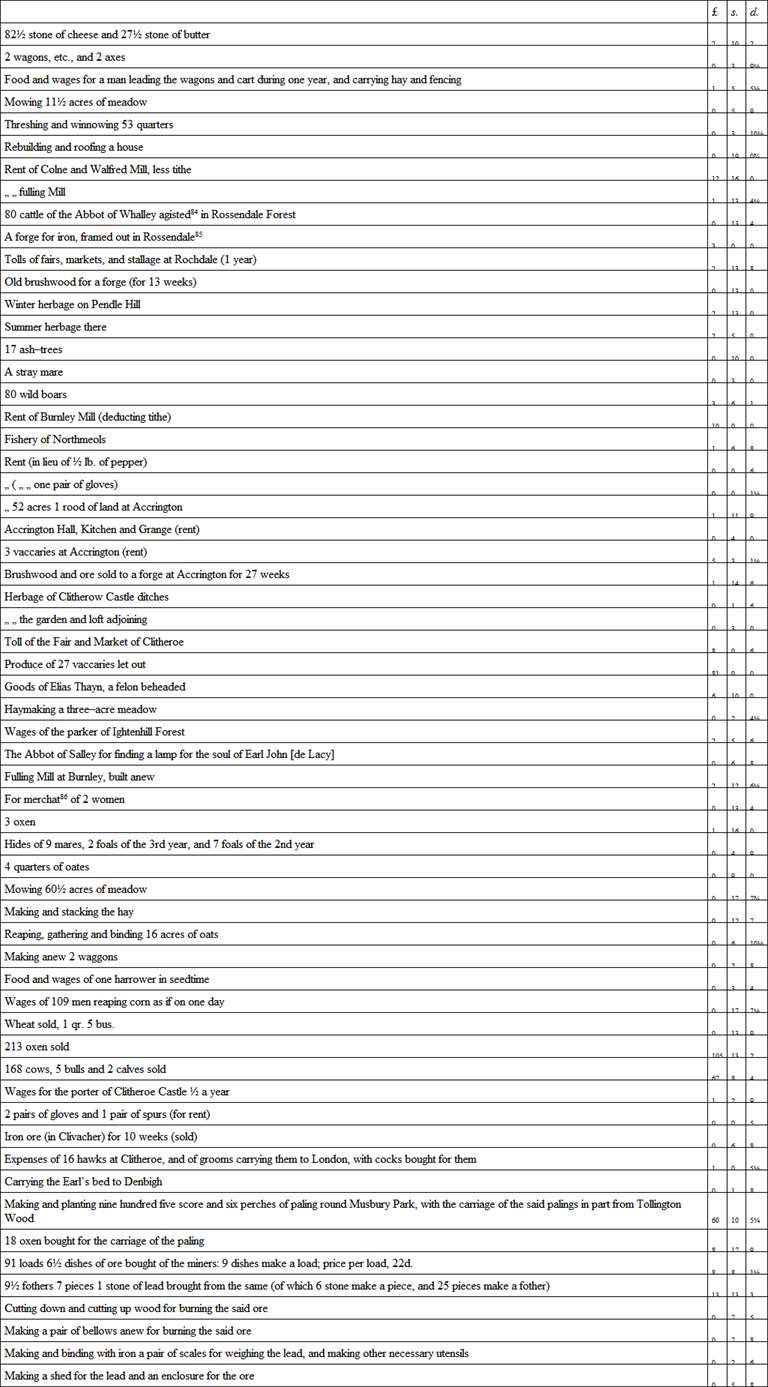

Clitheroe Castle, though perhaps never a very extensive fortification, is one of the oldest foundations in the county, probably dating back to Saxon times. It stands in a commanding situation on the summit of a rock rising out of the plain, about a mile from Pendle Hill; in Domesday Book it is described as the Castle of Roger (Roger de Lacy). Of the original building nothing is now left but the keep, a square tower of small dimensions. The honour dependent upon this castle extended over a very large area, part only of which is in Lancashire; it included Whalley, Blackburn, Chipping, Ribchester, Tottington (in Salford Hundred), and Rochdale, and consequently the manors of all these places were at one time held of the castle of Clitheroe. Henry de Lacy, second Earl of Lincoln and great–grandson of Roger de Lacy, was born in 1250, and, like his ancestor, he made this castle his Lancashire stronghold and residence, and here each year his tenants and the stewards of the various manors attended his courts to render in their accounts and offer the suit and service required. The town of Clitheroe must, on the occasions when the Earl was at the castle, have put on a festive appearance, as the lord of the honour is said to have assumed an almost regal state. Several of the accounts of the stewards, parkers, and other servants of the Earl have fortunately been preserved, and we are by them enabled to get a glimpse at the social life of the Lancashire people between the years 1295 and 1305.81 We find that, besides the forests of Pendle, Accrington, Rossendale and Trawden, there were parks at Ightenhill and Musbury, well stocked with deer. There were over twenty vaccaries, or breeding farms, all of which added to the Earl’s income. On the estates were iron forges, and iron smelting was practised, and of course coal was dug up from the seams lying near the surface.

The following extracts from these rolls will serve to illustrate the historical value of the details furnished.82 Full allowance must be made by the reader for the difference in value of money between the thirteenth and the nineteenth centuries;83 and it must be remembered that labourers in addition to their wages generally received rations, and were sometimes housed.

84 Agisted = allowed to graze in the forest.

85 In 1338 the Abbot of Whalley charged certain persons armed “with swords and bows and arrows” with having taken away his goods, and, inter alia, 300 pieces of iron, and from the evidence adduced it appears that near Whitworth (in Rochdale parish), which is adjoining Rossendale, the Abbot and others were accustomed to dig up the ironstone and smelt it. (See Fishwick’s “History of Rochdale,” p. 84.)

86 Merchats = fines paid to the lord for marriage of a daughter. The above sum was the sum returned to the tenant because it was found that the women were not daughters of villeins.

From these references to smelting of lead it is quite clear that the operation was being performed here for the first time – probably as an experiment; but where did the ore come from? A reference is made to carrying ore from Baxenden (near Accrington) to Bradford (in Salford), but there is no evidence that lead was ever worked or discovered there, so probably the ore was imported from some lead–mining district.

Sea–coal (carbones maris) is thrice mentioned as being paid for in the Cliviger and Colne district, where it had no doubt been dug up.

The Compotus of the Earl of Lincoln contains many details referring to the various vaccaries in his holding; each of these was looked after by an instaurator, or bailiff, who lived generally at the Grange, whilst his various assistants occupied the humbler “booths.” Accrington vaccary may be accepted as a sample; there were there when the stock was taken on January 26, 1297, 106 cows, 3 bulls, 24 steers, 24 heifers, 31 yearlings, and 46 calves.

In this, as in all the other vaccaries, many cattle died from murrain, and some fell victims to the wolves which infested all the forests.

Toward the end of the year 1349 Lancashire was visited with the pestilence known as the Black Death, which about this time broke out again and again in almost every part of the civilized world. By a fortunate accident a record of the dreadful ravages made by this disease in the Hundred of Amounderness has been preserved.

It appears that the Archdeacon of Richmond (in whose jurisdiction was the whole of Lancashire north of the Ribble) and Adam de Kirkham, Dean of Amounderness, his Proctor, had a dispute relative to the fees for the probate of wills and the administration of the effects of persons dying intestate; the matter was referred to a jury of laymen, whose report furnishes a return of the number of deaths from the plague, and other details which may be accepted as at all events fairly correct, although the district must have been at the time in such a state of panic as to render the collection of statistical facts extremely difficult.

In ten parishes in Amounderness, 13,180 died between September 8, 1349, and January 11, 1349–50, and nine benefices were vacant in consequence. The chapel of the hospital of St. Mary Magdalen at Preston was without a priest for eight weeks, and in that town 3,000 men and women perished; of these, 300 had goods worth £5, and left wills, but 200 others with the like property made no wills. At Poulton–le–Fylde the deaths amounted to 800; at Lancaster 3,000 died, at Garstang 2,000, and at Kirkham 3,000, whilst the other less thickly populated places each lost more or less of its inhabitants.87 How the rest of Lancashire fared under this dreadful visitation is uncertain, but Manchester and a few other places in the south of the county are said to have suffered very heavily.

We have already seen that Edmund Crouchback, the favourite son of the King, had given to him the honour of Lancaster, which was confirmed by Henry III., who granted (in 1267) to him the castle of Kenilworth, the castle and manor of Monmouth, and other territories in various parts of the kingdom. The founder of the house of Lancaster died at Bayonne in May, 1296, and Thomas, his eldest son, succeeded to his vast possessions in Lancashire and elsewhere; and in 1297–98 he passed through the county in company with his royal master on his way to Scotland; in 1310 he married Alice, the sole daughter of Henry de Lacy, Earl of Lincoln, and then got possession of the great estates in the county which had for several generations belonged to the De Lacy family.

In 1316–17 one of the followers of the Earl of Lancaster, in order, it is said, to ingratiate himself with the King, invaded some of the possessions of the Earl, and the result was a pitched battle, which took place near Preston, in which Banastre and his army were completely defeated.

The subsequent quarrel between this celebrated Earl of Lancaster and the King is well known, and need not be repeated here; finding himself unable to meet the royal forces, he retired to his castle at Pontefract, where he was ultimately retained as a prisoner, and near to which town, after suffering great indignities and insults, he was executed as a traitor, March 22, 1321–22. Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, was succeeded by Henry his brother, who, on the reversion of the attainder of the latter, had granted to him, in A.D. 1327, the issues and arrearages of the lands, etc., which had belonged to the earldom of Lancaster and Leicester. On the death of Henry, Earl of Lancaster, the title went to his son Henry (called Grismond), who became Earl of Lancaster, Derby, and Lincoln, and was, as a crowning honour, for his distinguished military services, created in 1353 the first Duke of Lancaster, for his life, having his title confirmed by the prelates and peers assembled in Parliament at Westminster. He was empowered to hold a chancery court for Lancaster, and to issue writs there under his own seal, and to enjoy the same liberties and regalities as belonged to a county palatine,88 in as ample manner as the Earl of Chester had within that county. Henry, who for his deeds of piety was styled “the Good Duke of Lancaster,” obtained a license to go to Syracuse to fight against the infidels there; but being taken prisoner in Germany, he only regained his liberty by the payment of a heavy fine. Towards the close of his life he lived in great state in his palace of Savoy, and became a great patron to several religious houses, one of which was Whalley Abbey (see Chapter IX.). He died March 24, 1360–61, leaving two daughters, one of whom (Blanch) was married to John of Gaunt, Earl of Richmond, fourth son of Edward III.; and to her he bequeathed his Lancashire possessions, and on the death of her sister Maud, the widow of the Duke of Bavaria, in A.D. 1362, without issue, she became entitled to the remainder of the vast estates of her late father.