полная версия

полная версияThe World as Will and Idea (Vol. 2 of 3)

But in consequence of that unduly wide view in abstract thought of the conception cause, which was considered above, it has been confounded with the conception of force. This is something completely different from the cause, but yet is that which imparts to every cause its causality, i. e., the capability of producing an effect. I have explained this fully and thoroughly in the second book of the first volume, also in “The Will in Nature,” and finally also in the second edition of the essay on the principle of sufficient reason, § 20, p. 44 (third edition, p. 45). This confusion is to be found in its most aggravated form in Maine de Biran's book mentioned above, and this is dealt with more fully in the place last referred to; but apart from this it is also very common; for example, when people seek for the cause of any original force, such as gravitation. Kant himself (Über den Einzig Möglichen Beweisgrund, vol. i. p. 211-215 of Rosenkranz's edition) calls the forces of nature “efficient causes,” and says “gravity is a cause.” Yet it is impossible to see to the bottom of his thought so long as force and cause are not distinctly recognised as completely different. But the use of abstract conceptions leads very easily to their confusion if the consideration of their origin is set aside. The knowledge of causes and effects, always perceptive, which rests on the form of the understanding, is neglected in order to stick to the abstraction cause. In this way alone is the conception of causality, with all its simplicity, so very frequently wrongly apprehended. Therefore even in Aristotle (“Metaph.,” iv. 2) we find causes divided into four classes which are utterly falsely, and indeed crudely conceived. Compare with it my classification of causes as set forth for the first time in my essay on sight and colour, chap. 1, and touched upon briefly in the sixth paragraph of the first volume of the present work, but expounded at full length in my prize essay on the freedom of the will, p. 30-33. Two things in nature remain untouched by that chain of causality which stretches into infinity in both directions; these are matter and the forces of nature. They are both conditions of causality, while everything else is conditioned by it. For the one (matter) is that in which the states and their changes appear; the other (forces of nature) is that by virtue of which alone they can appear at all. Here, however, one must remember that in the second book, and later and more thoroughly in “The Will in Nature,” the natural forces are shown to be identical with the will in us; but matter appears as the mere visibility of the will; so that ultimately it also may in a certain sense be regarded as identical with the will.

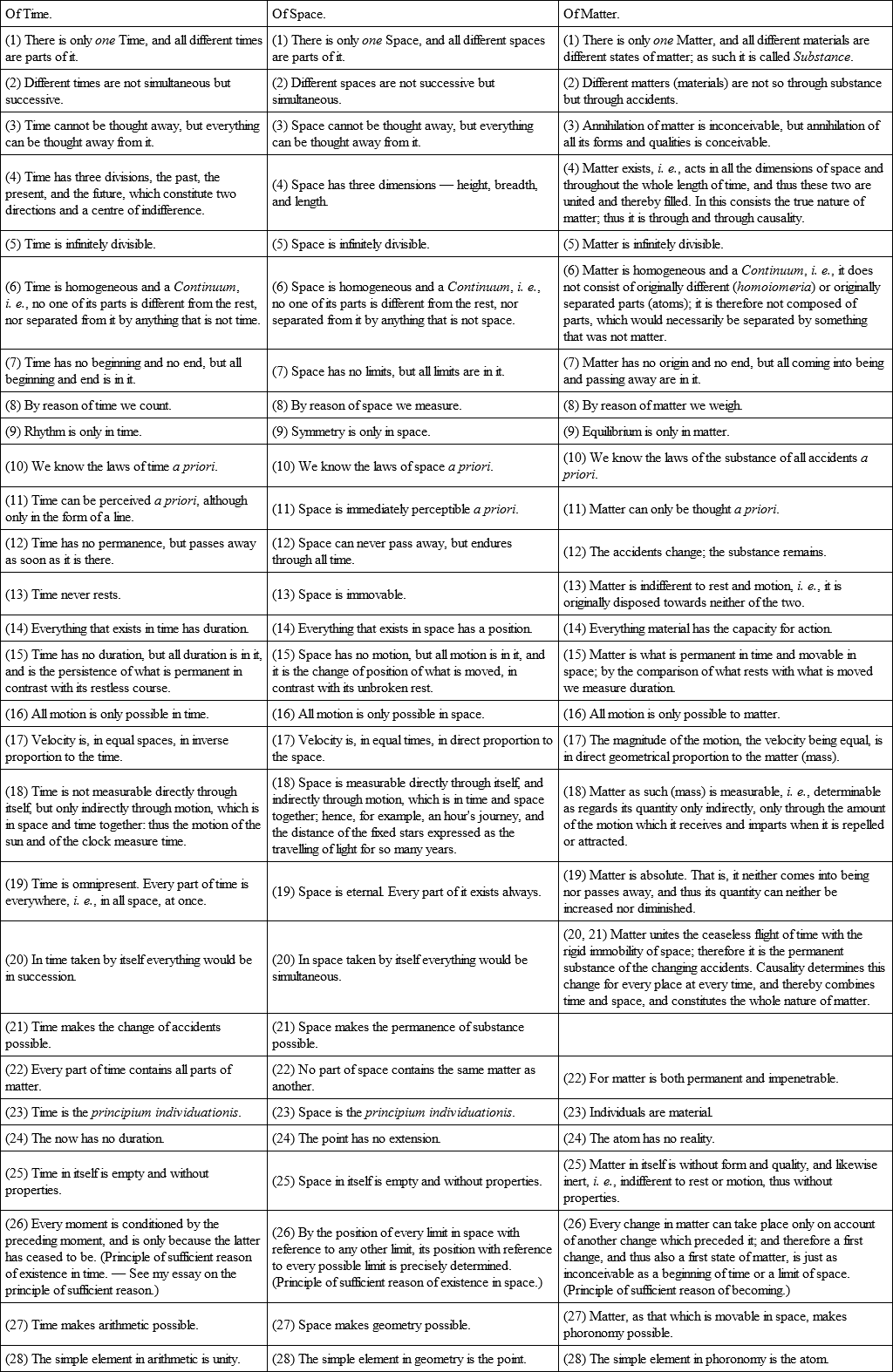

On the other hand, not less true and correct is what is explained in § 4 of the first book, and still better in the second edition of the essay on the principle of sufficient reason at the end of § 21, p. 77 (third edition, p. 82), that matter is causality itself objectively comprehended, for its entire nature consists in acting in general, so that it itself is thus the activity (ενεργεια = reality) of things generally, as it were the abstraction of all their different kinds of acting. Accordingly, since the essence, essentia, of matter consists in action in general, and the reality, existentia, of things consists in their materiality, which thus again is one with action in general, it may be asserted of matter that in it existentia and essentia unite and are one, for it has no other attribute than existence itself in general and independent of all fuller definitions of it. On the other hand, all empirically given matter, thus all material or matter in the special sense (which our ignorant materialists at the present day confound with matter), has already entered the framework of the forms and manifests itself only through their qualities and accidents, because in experience every action is of quite a definite and special kind, and is never merely general. Therefore pure matter is an object of thought alone, not of perception, which led Plotinus (Enneas II., lib. iv., c. 8 & 9) and Giordano Bruno (Della Causa, dial. 4) to make the paradoxical assertion that matter has no extension, for extension is inseparable from the form, and that therefore it is incorporeal. Yet Aristotle had already taught that it is not a body although it is corporeal: “σωμα μεν ουκ αν ειη, σωματικη δε” (Stob. Ecl., lib. i., c. 12, § 5). In reality we think under pure matter only action, in the abstract, quite independent of the kind of action, thus pure causality itself; and as such it is not an object but a condition of experience, just like space and time. This is the reason why in the accompanying table of our pure a priori knowledge matter is able to take the place of causality, and therefore appears along with space and time as the third pure form, and therefore as dependent on our intellect.

This table contains all the fundamental truths which are rooted in our perceptive or intuitive knowledge a priori, expressed as first principles independent of each other. What is special, however, what forms the content of arithmetic and geometry, is not given here, nor yet what only results from the union and application of those formal principles of knowledge. This is the subject of the “Metaphysical First Principles of Natural Science” expounded by Kant, to which this table in some measure forms the propædutic and introduction, and with which it therefore stands in direct connection. In this table I have primarily had in view the very remarkable parallelism of those a priori principles of knowledge which form the framework of all experience, but specially also the fact that, as I have explained in § 4 of the first volume, matter (and also causality) is to be regarded as a combination, or if it is preferred, an amalgamation, of space and time. In agreement with this, we find that what geometry is for the pure perception or intuition of space, and arithmetic for that of time, Kant's phoronomy is for the pure perception or intuition of the two united. For matter is primarily that which is movable in space. The mathematical point cannot even be conceived as movable, as Aristotle has shown (“Physics,” vi. 10). This philosopher also himself provided the first example of such a science, for in the fifth and sixth books of his “Physics” he determined a priori the laws of rest and motion.

Now this table may be regarded at pleasure either as a collection of the eternal laws of the world, and therefore as the basis of our ontology, or as a chapter of the physiology of the brain, according as one assumes the realistic or the idealistic point of view; but the second is in the last instance right. On this point, indeed, we have already come to an understanding in the first chapter; yet I wish further to illustrate it specially by an example. Aristotle's book “De Xenophane,” &c., commences with these weighty words of Xenophanes: “Αϊδιον ειναι φησιν, ει τι εστιν, ειπερ μη ενδεχεται γενεσθαι μηδεν εκ μηδενος.” (Æternum esse, inquit, quicquid est, siquidem fieri non potest, ut ex nihilo quippiam existat.) Here, then, Xenophanes judges as to the origin of things, as regards its possibility, and of this origin he can have had no experience, even by analogy; nor indeed does he appeal to experience, but judges apodictically, and therefore a priori. How can he do this if as a stranger he looks from without into a world that exists purely objectively, that is, independently of his knowledge? How can he, an ephemeral being hurrying past, to whom only a hasty glance into such a world is permitted, judge apodictically, a priori and without experience concerning that world, the possibility of its existence and origin? The solution of this riddle is that the man has only to do with his own ideas, which as such are the work of his brain, and the constitution of which is merely the manner or mode in which alone the function of his brain can be fulfilled, i. e., the form of his perception. He thus judges only as to the phenomena of his own brain, and declares what enters into its forms, time, space, and causality, and what does not. In this he is perfectly at home and speaks apodictically. In a like sense, then, the following table of the Prædicabilia a priori of time, space, and matter is to be taken: —

Prædicabilia A Priori.

Notes to the Annexed Table.

(1) To No. 4 of Matter.

The essence of matter is acting, it is acting itself, in the abstract, thus acting in general apart from all difference of the kind of action: it is through and through causality. On this account it is itself, as regards its existence, not subject to the law of causality, and thus has neither come into being nor passes away, for otherwise the law of causality would be applied to itself. Since now causality is known to us a priori, the conception of matter, as the indestructible basis of all that exists, can so far take its place in the knowledge we possess a priori, inasmuch as it is only the realisation of an a priori form of our knowledge. For as soon as we see anything that acts or is causally efficient it presents itself eo ipso as material, and conversely anything material presents itself as necessarily active or causally efficient. They are in fact interchangeable conceptions. Therefore the word “actual” is used as synonymous with “material;” and also the Greek κατ᾽ ενεργειαν, in opposition to κατα δυναμιν, reveals the same source, for ενεργεια signifies action in general; so also with actu in opposition to potentia, and the English “actually” for “wirklich.” What is called space-occupation, or impenetrability, and regarded as the essential predicate of body (i. e. of what is material), is merely that kind of action which belongs to all bodies without exception, the mechanical. It is this universality alone, by virtue of which it belongs to the conception of body, and follows a priori from this conception, and therefore cannot be thought away from it without doing away with the conception itself – it is this, I say, that distinguishes it from any other kind of action, such as that of electricity or chemistry, or light or heat. Kant has very accurately analysed this space-occupation of the mechanical mode of activity into repulsive and attractive force, just as a given mechanical force is analysed into two others by means of the parallelogram of forces. But this is really only the thoughtful analysis of the phenomenon into its two constituent parts. The two forces in conjunction exhibit the body within its own limits, that is, in a definite volume, while the one alone would diffuse it into infinity, and the other alone would contract it to a point. Notwithstanding this reciprocal balancing or neutralisation, the body still acts upon other bodies which contest its space with the first force, repelling them, and with the other force, in gravitation, attracting all bodies in general. So that the two forces are not extinguished in their product, as, for instance, two equal forces acting in different directions, or +E and – E, or oxygen and hydrogen in water. That impenetrability and gravity really exactly coincide is shown by their empirical inseparableness, in that the one never appears without the other, although we can separate them in thought.

I must not, however, omit to mention that the doctrine of Kant referred to, which forms the fundamental thought of the second part of his “Metaphysical First Principles of Natural Science,” thus of the Dynamics, was distinctly and fully expounded before Kant by Priestley, in his excellent “Disquisitions on Matter and Spirit,” § 1 and 2, a book which appeared in 1777, and the second edition in 1782, while Kant's work was published in 1786. Unconscious recollection may certainly be assumed in the case of subsidiary thoughts, flashes of wit, comparisons, &c., but not in the case of the principal and fundamental thought. Shall we then believe that Kant silently appropriated such important thoughts of another man? and this from a book which at that time was new? Or that this book was unknown to him, and that the same thoughts sprang up in two minds within a short time? The explanation, also, which Kant gives, in the “Metaphysical First Principles of Natural Science” (first edition, p. 88; Rosenkranz's edition, p. 384), of the real difference between fluids and solids, is in substance already to be found in Kaspar Freidr. Wolff's “Theory of Generation,” Berlin 1764, p. 132. But what are we to say if we find Kant's most important and brilliant doctrine, that of the ideality of space and the merely phenomenal existence of the corporeal world, already expressed by Maupertuis thirty years earlier? This will be found more fully referred to in Frauenstädt's letters on my philosophy, Letter 14. Maupertuis expresses this paradoxical doctrine so decidedly, and yet without adducing any proof of it, that one must suppose that he also took it from somewhere else. It is very desirable that the matter should be further investigated, and as this would demand tiresome and extensive researches, some German Academy might very well make the question the subject of a prize essay. Now in the same relation as that in which Kant here stands to Priestley, and perhaps also to Kaspar Wolff, and Maupertuis or his predecessor, Laplace stands to Kant. For the principal and fundamental thought of Laplace's admirable and certainly correct theory of the origin of the planetary system, which is set forth in his “Exposition du Système du Monde,” liv. v. c. 2, was expressed by Kant nearly fifty years before, in 1755, in his “Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels,” and more fully in 1763 in his “Einzig möglichen Beweisgrund des Daseyns Gottes,” ch. 7. Moreover, in the later work he gives us to understand that Lambert in his “Kosmologischen Briefen,” 1761, tacitly adopted that doctrine from him, and these letters at the same time also appeared in French (Lettres Cosmologiques sur la Constitution de l'Univers). We are therefore obliged to assume that Laplace knew that Kantian doctrine. Certainly he expounds the matter more thoroughly, strikingly, and fully, and at the same time more simply than Kant, as is natural from his more profound astronomical knowledge; yet in the main it is to be found clearly expressed in Kant, and on account of the importance of the matter, would alone have been sufficient to make his name immortal. It cannot but disturb us very much if we find minds of the first order under suspicion of dishonesty, which would be a scandal to those of the lowest order. For we feel that theft is even more inexcusable in a rich man than in a poor one. We dare not, however, be silent; for here we are posterity, and must be just, as we hope that posterity will some day be just to us. Therefore, as a third example, I will add to these cases, that the fundamental thoughts of the “Metamorphosis of Plants,” by Goethe, were already expressed by Kaspar Wolff in 1764 in his “Theory of Generation,” p. 148, 229, 243, &c. Indeed, is it otherwise with the system of gravitation? the discovery of which is on the Continent of Europe always ascribed to Newton, while in England the learned at least know very well that it belongs to Robert Hooke, who in the year 1666, in a “Communication to the Royal Society,” expounds it quite distinctly, although only as an hypothesis and without proof. The principal passage of this communication is quoted in Dugald Stewart's “Philosophy of the Human Mind,” and is probably taken from Robert Hooke's Posthumous Works. The history of the matter, and how Newton got into difficulty by it, is also to be found in the “Biographie Universelle,” article Newton. Hooke's priority is treated as an established fact in a short history of astronomy, Quarterly Review, August 1828. Further details on this subject are to be found in my “Parerga,” vol. ii., § 86 (second edition, § 88). The story of the fall of an apple is a fable as groundless as it is popular, and is quite without authority.

(2) To No. 18 of Matter.

The quantity of a motion (quantitas motus, already in Descartes) is the product of the mass into the velocity.

This law is the basis not only of the doctrine of impact in mechanics, but also of that of equilibrium in statics. From the force of impact which two bodies with the same velocity exert the relation of their masses to each other may be determined. Thus of two hammers striking with the same velocity, the one which has the greater mass will drive the nail deeper into the wall or the post deeper into the earth. For example, a hammer weighing six pounds with a velocity = 6 effects as much as a hammer weighing three pounds with a velocity = 12, for in both cases the quantity of motion or the momentum = 36. Of two balls rolling at the same pace, the one which has the greater mass will impel a third ball at rest to a greater distance than the ball of less mass can. For the mass of the first multiplied by the same velocity gives a greater quantity of motion, or a greater momentum. The cannon carries further than the gun, because an equal velocity communicated to a much greater mass gives a much greater quantity of motion, which resists longer the retarding effect of gravity. For the same reason, the same arm will throw a lead bullet further than a stone one of equal magnitude, or a large stone further than quite a small one. And therefore also a case-shot does not carry so far as a ball-shot.

The same law lies at the foundation of the theory of the lever and of the balance. For here also the smaller mass, on the longer arm of the lever or beam of the balance, has a greater velocity in falling; and multiplied by this it may be equal to, or indeed exceed, the quantity of motion or the momentum of the greater mass at the shorter arm of the lever. In the state of rest brought about by equilibrium this velocity exists merely in intention or virtually, potentiâ, not actu; but it acts just as well as actu, which is very remarkable.

The following explanation will be more easily understood now that these truths have been called to mind.

The quantity of a given matter can only be estimated in general according to its force, and its force can only be known in its expression. Now when we are considering matter only as regards its quantity, not its quality, this expression can only be mechanical, i. e., it can only consist in motion which it imparts to other matter. For only in motion does the force of matter become, so to speak, alive; hence the expression vis viva for the manifestation of force of matter in motion. Accordingly the only measure of the quantity of a given matter is the quantity of its motion, or its momentum. In this, however, if it is given, the quantity of matter still appears in conjunction and amalgamated with its other factor, velocity. Therefore if we want to know the quantity of matter (the mass) this other factor must be eliminated. Now the velocity is known directly; for it is S/T. But the other factor, which remains when this is eliminated, can always be known only relatively in comparison with other masses, which again can only be known themselves by means of the quantity of their motion, or their momentum, thus in their combination with velocity. We must therefore compare one quantity of motion with the other, and then subtract the velocity from both, in order to see how much each of them owed to its mass. This is done by weighing the masses against each other, in which that quantity of motion is compared which, in each of the two masses, calls forth the attractive power of the earth that acts upon both only in proportion to their quantity. Therefore there are two kinds of weighing. Either we impart to the two masses to be compared equal velocity, in order to find out which of the two now communicates motion to the other, thus itself has a greater quantity of motion, which, since the velocity is the same on both sides, is to be ascribed to the other factor of the quantity of motion or the momentum, thus to the mass (common balance). Or we weigh, by investigating how much more velocity the one mass must receive than the other has, in order to be equal to the latter in quantity of motion or momentum, and therefore allow no more motion to be communicated to itself by the other; for then in proportion as its velocity must exceed that of the other, its mass, i. e., the quantity of its matter, is less than that of the other (steelyard). This estimation of masses by weighing depends upon the favourable circumstance that the moving force, in itself, acts upon both quite equally, and each of the two is in a position to communicate to the other directly its surplus quantity of motion or momentum, so that it becomes visible.

The substance of these doctrines has long ago been expressed by Newton and Kant, but through the connection and the clearness of this exposition I believe I have made it more intelligible, so that that insight is possible for all which I regarded as necessary for the justification of proposition No. 18.

Second Half. The Doctrine of the Abstract Idea, or Thinking

Chapter V.16 On The Irrational Intellect

It must be possible to arrive at a complete knowledge of the consciousness of the brutes, for we can construct it by abstracting certain properties of our own consciousness. On the other hand, there enters into the consciousness of the brute instinct, which is much more developed in all of them than in man, and in some of them extends to what we call mechanical instinct.

The brutes have understanding without having reason, and therefore they have knowledge of perception but no abstract knowledge. They apprehend correctly, and also grasp the immediate causal connection, in the case of the higher species even through several links of its chain, but they do not, properly speaking, think. For they lack conceptions, that is, abstract ideas. The first consequence of this, however, is the want of a proper memory, which applies even to the most sagacious of the brutes, and it is just this which constitutes the principal difference between their consciousness and that of men. Perfect intelligence depends upon the distinct consciousness of the past and of the eventual future, as such, and in connection with the present. The special memory which this demands is therefore an orderly, connected, and thinking retrospective recollection. This, however, is only possible by means of general conceptions, the assistance of which is required by what is entirely individual, in order that it may be recalled in its order and connection. For the boundless multitude of things and events of the same and similar kinds, in the course of our life, does not admit directly of a perceptible and individual recollection of each particular, for which neither the powers of the most comprehensive memory nor our time would be sufficient. Therefore all this can only be preserved by subsuming it under general conceptions, and the consequent reference to relatively few principles, by means of which we then have always at command an orderly and adequate survey of our past. We can only present to ourselves in perception particular scenes of the past, but the time that has passed since then and its content we are conscious of only in the abstract by means of conceptions of things and numbers which now represent days and years, together with their content. The memory of the brutes, on the contrary, like their whole intellect, is confined to what they perceive, and primarily consists merely in the fact that a recurring impression presents itself as having already been experienced, for the present perception revivifies the traces of an earlier one. Their memory is therefore always dependent upon what is now actually present. Just on this account, however, this excites anew the sensation and the mood which the earlier phenomenon produced. Thus the dog recognises acquaintances, distinguishes friends from enemies, easily finds again the path it has once travelled, the houses it has once visited, and at the sight of a plate or a stick is at once put into the mood associated with them. All kinds of training depend upon the use of this perceptive memory and on the force of habit, which in the case of animals is specially strong. It is therefore just as different from human education as perception is from thinking. We ourselves are in certain cases, in which memory proper refuses us its service, confined to that merely perceptive recollection, and thus we can measure the difference between the two from our own experience. For example, at the sight of a person whom it appears to us we know, although we are not able to remember when or where we saw him; or again, when we visit a place where we once were in early childhood, that is, while our reason was yet undeveloped, and which we have therefore entirely forgotten, and yet feel that the present impression is one which we have already experienced. This is the nature of all the recollections of the brutes. We have only to add that in the case of the most sagacious this merely perceptive memory rises to a certain degree of phantasy, which again assists it, and by virtue of which, for example, the image of its absent master floats before the mind of the dog and excites a longing after him, so that when he remains away long it seeks for him everywhere. Its dreams also depend upon this phantasy. The consciousness of the brutes is accordingly a mere succession of presents, none of which, however, exist as future before they appear, nor as past after they have vanished; which is the specific difference of human consciousness. Hence the brutes have infinitely less to suffer than we have, because they know no other pains but those which the present directly brings. But the present is without extension, while the future and the past, which contain most of the causes of our suffering, are widely extended, and to their actual content there is added that which is merely possible, which opens up an unlimited field for desire and aversion. The brutes, on the contrary, undisturbed by these, enjoy quietly and peacefully each present moment, even if it is only bearable. Human beings of very limited capacity perhaps approach them in this. Further, the sufferings which belong purely to the present can only be physical. Indeed the brutes do not properly speaking feel death: they can only know it when it appears, and then they are already no more. Thus then the life of the brute is a continuous present. It lives on without reflection, and exists wholly in the present; even the great majority of men live with very little reflection. Another consequence of the special nature of the intellect of the brutes, which we have explained is the perfect accordance of their consciousness with their environment. Between the brute and the external world there is nothing, but between us and the external world there is always our thought about it, which makes us often inapproachable to it, and it to us. Only in the case of children and very primitive men is this wall of partition so thin that in order to see what goes on in them we only need to see what goes on round about them. Therefore the brutes are incapable alike of purpose and dissimulation; they reserve nothing. In this respect the dog stands to the man in the same relation as a glass goblet to a metal one, and this helps greatly to endear the dog so much to us, for it affords us great pleasure to see all those inclinations and emotions which we so often conceal displayed simply and openly in him. In general, the brutes always play, as it were, with their hand exposed; and therefore we contemplate with so much pleasure their behaviour towards each other, both when they belong to the same and to different species. It is characterised by a certain stamp of innocence, in contrast to the conduct of men, which is withdrawn from the innocence of nature by the entrance of reason, and with it of prudence or deliberation. Hence human conduct has throughout the stamp of intention or deliberate purpose, the absence of which, and the consequent determination by the impulse of the moment, is the fundamental characteristic of all the action of the brutes. No brute is capable of a purpose properly so-called. To conceive and follow out a purpose is the prerogative of man, and it is a prerogative which is rich in consequences. Certainly an instinct like that of the bird of passage or the bee, still more a permanent, persistent desire, a longing like that of the dog for its absent master, may present the appearance of a purpose, with which, however, it must not be confounded. Now all this has its ultimate ground in the relation between the human and the brute intellect, which may also be thus expressed: The brutes have only direct knowledge, while we, in addition to this, have indirect knowledge; and the advantage which in many things – for example, in trigonometry and analysis, in machine work instead of hand work, &c. – indirect has over direct knowledge appears here also. Thus again we may say: The brutes have only a single intellect, we a double intellect, both perceptive and thinking, and the operation of the two often go on independently of each other. We perceive one thing, and we think another. Often, again, they act upon each other. This way of putting the matter enables us specially to understand that natural openness and naivete of the brutes, referred to above, as contrasted with the concealment of man.