полная версия

полная версияFifty Years In The Northwest

Various schemes for internal improvement were brought before the convention and ably advocated, but each in the interest of a particular section. The members from Florida wanted a ship canal for that State. Illinois and Eastern Iowa advocated the Hennepin canal scheme. Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Western Iowa, Dakota, and Montana demanded the improvement of the Missouri river. Wisconsin and Northern Iowa the completion of the Fox and Wisconsin canal. Minnesota and Wisconsin agreed with all for the improvement of the Mississippi from the falls of St. Anthony to the Balize, for the improvement of the Sault Ste. Marie canal, and for the internal improvements asked for generally in the states and territories represented.

The result was the passage of a series of resolutions recommending a liberal policy in the distribution of improvements, and favoring every meritorious project for the increase of facilities for water transportation, but recommending as a subject of paramount importance the immediate and permanent improvement of the Mississippi and Missouri rivers and their navigable tributaries. It was recommended that the depth of the Mississippi be increased to six feet between Cario and the falls of St. Anthony. The Hennepin canal was strongly indorsed, as was also the improvement of the Sault Ste. Marie, and of the navigation of Wisconsin and Fox rivers, of the Red River of the North, and of the Chippewa, St. Croix and Minnesota rivers. The convention unanimously recommended as a sum proper for these improvements the appropriation of $25,000,000.

Some of the papers presented were elaborately prepared, and deserve to be placed on permanent record. The memorial of Mr. E. W. Durant, of Stillwater, contains many valuable statistics. We quote that portion containing a statement of the resources and commerce of the valleys of the Mississippi and St. Croix:

"The Northwestern States have not had the recognition that is due to the agricultural and commercial requirements of this vast and poplous territory, whose granaries and fields not only feed the millions of this continent, but whose annual export constitutes a most important factor in the food calculation of foreign nations. During the past decade the general government has expended $3,000,000 on the waterways of the Upper Mississippi. The improvements inaugurated by the general government in removing many of the serious impediments to navigation warrants the belief that still more extensive improvements should be made. It is an error to suppose that the palmy days of steamboating on western rivers has passed. In demonstration of this take the quantity of lumber sent down the Mississippi. There was shipped from the St. Croix river during the year 1884 to various distributing points along the Mississippi river 250,000,000 feet of lumber, 40,000,000 of lath, 37,000,000 of shingles, 2,000,000 of pickets; from the Chippewa river during the same period, 883,000,000 feet of lumber, 223,000,000 of shingles and 102,000,000 of lath and pickets; from Black river during the same period was shipped 250,000,000 feet of lumber, 40,000,000 shingles, and 32,000,000 lath and pickets, aggregating 1,383,000,000 feet of lumber, 300,000,000 of shingles and 176,000,000 of lath. The tonnage of this product alone foots up over 3,000,000 tons. The lumber value of raft and cargoes annually floated to market on the Mississippi will not vary far from $20,000,000. The capital invested in steamboats, 100 in number, used for towing purposes is $1,250,000; while the saw mills, timber plants and other investments incidental to the prosecution of this branch of industry will foot up fully $500,000; while the labor and their dependences engaged in this pursuit alone will equal the population of one of our largest western states. There are sixteen bridges spanning the river between St. Paul and St. Louis, and it is important that some additional safeguards be thrown around these bridges to afford greater safety to river commerce."

Mr. Durant says there has been a general cry for some time past that the days of steamboating on the Northern Mississippi and tributaries were over; but he thinks it will be forcibly shown in the coming convention that, if they are, the only cause for it is the extremely short and uncertain seasons for steamboating, resulting from the neglected and filled up channels. If the channels can be improved, so that steamers can be sure of five months' good running each year, he thinks they will prove to be one of the most important means of transportation in the Upper Mississippi valley. They will then be used for the transportation up and down stream of all heavy and slow freights in preference to railroads, on account of cheapness. It would prove a new and the greatest era in upper river steamboating.

It appears from a report made at the convention, that during the year 1884 there were 175 steamboats plying on the Mississippi from St. Louis to points above. Two thousand seven hundred rafts from the St. Croix and Chippewa passed the Winona bridge, and the total number of feet of logs and lumber floated down the Mississippi from the St. Croix, Chippewa and Black rivers was 1,366,000,000. The total passages of steamers through the Winona bridge for 1887 was 4,492. On the St. Croix, above Lake St. Croix, during the season of 1887 there were 3 steamers and 25 barges engaged in freight and passenger traffic only. The steamers made 141 round trips between Stillwater and Taylor's Falls, 75 round trips between Marine and St. Paul, and 20 round trips between Franconia and St. Paul.

The following is a showing of the lumber, logs, rafting, and towing business on the St. Croix during 1887: There were 51 steamers engaged in towing logs and lumber out of the St. Croix and down the Mississippi, the total number of feet handled by them being 250,000,000, board measure: The total number of feet of logs (board measure) which passed through the St. Croix boom in 1887 was 325,000,000. The lumber manufacture of the St. Croix during that year was valued at $2,393,323.

RESOLUTION INTRODUCED AT THE WATERWAYS CONVENTION HELD IN ST. PAUL, SEPTEMBER, 1885

Whereas, The North American continent is penetrated by two great water systems both of which originate upon the tablelands of Minnesota, one the Mississippi river and its tributaries, reaching southward from the British line to the Gulf of Mexico, watering the greatest body of fertile land on the globe, – the future seat of empire of the human family on earth, – the other the chain of great lakes flowing eastwardly and constituting with the St. Lawrence river a great water causeway in the direct line of the flow of the world's commerce from the heart of the continent to the Atlantic; and

Whereas, Between the navigable waters of these continental dividing systems there is but a gap of ninety miles in width from Taylor's Falls on the St. Croix, to Duluth on Lake Superior, through a region of easily worked drift formation, with a rise of but five hundred and sixty feet to overcome, and plentifully supplied with water from the highest point of the water-shed; therefore,

Resolved. That we demand of Congress the construction of a canal from Taylor's Falls to Duluth, using the Upper St. Croix and the St. Louis rivers as far as the same can be made navigable, the said canal to be forever free of toll or charge, and to remain a public highway for the interchange of the productions of the Mississippi valley and the valley of the great lakes; and should the railway interests of the country prove powerful enough to prevent congressional action to this end, we call upon the states of the Northwest to unite and build, at their own cost, such a canal, believing that the increased value of the productions of the country would speedily repay the entire outlay.

EARLY STEAMBOAT NAVIGATION

The Pennsylvania was the first steamer that descended the Mississippi. She came down the Ohio from Pittsburgh, creating the utmost terror in the minds of the simple-hearted people who had lately been rather rudely shaken by an earthquake, and supposed the noise of the coming steamer to be but the precursor of another shake. When the Pennsylvania approached Shawneetown, Illinois, the people crowded the river shore, and in their alarm fell down upon their knees and prayed to be delivered from the muttering, roaring earthquake coming down the river, its furnaces glowing like the open portals of the nether world. Many fled to the hills in utter dismay at the frightful appearance of the hitherto unknown monster, and the dismal sounds it emitted. It produced the same and even greater terror in the scant settlements of the Lower Mississippi.

In 1823 Capt. Shreve commanded the Gen. Washington, the fastest boat that had as yet traversed the western rivers. This year the Gen. Washington made the trip from New Orleans to Louisville, Kentucky, in twenty-five days. When at Louisville he anchored his boat in the middle of the river and fired twenty-five guns in honor of the event, one for each day out. The population of Louisville feted and honored the gallant captain for his achievement. He was crowned with flowers, and borne through the streets by the huzzaing crowd. A rich banquet was spread, and amidst the hilarity excited by the flowing bowl, the captain made an eloquent speech which was vociferously applauded. He declared that the time made by the Gen. Washington could never be equaled by any other boat. Curiously enough, some later in the season, the Tecumseh made the trip in nine days. The time made by the Tecumseh was not beaten until 1833, when the Shepherdess carried away the laurels for speed.

We have but little definite information as to navigation on the Mississippi during the ten years subsequent to the trip of the Pennsylvania. The solitude of the Upper Mississippi was unbroken by the advent of any steamer until the year 1823. On the second of May in that year the Virginia, a steamer 118 feet in length, 22 in width, with a draught of 6 feet, left her moorings at St. Louis levee for Fort Snelling laden with stores for the fort. She was four days passing the Rock Island rapids, and made but slow progress throughout. It is heedless to say that the Indians were as much frightened at the appearance of the "fire canoe" as the settlers of the Ohio valley had been, and made quick time escaping to the hills.

Judge James H. Lockwood narrates (see Vol. II, Wisconsin Historical Collections, page 152) that in 1824 Capt. David G. Bates brought a small boat named the Putnam up to Prairie du Chien, and took it thence to Fort Snelling with supplies for the troops. The steamer Neville also made the voyage to Prairie du Chien in 1824. The following year came the steamer Mandan and in 1826 the Indiana and Lawrence. Fletcher Williams, in his history of St. Paul, says that from 1823 to 1826 as many as fifteen steamers had arrived at Fort Snelling, and that afterward their arrivals were more frequent.

During this primitive period, the steamboats had no regular time for arrival and departure at ports. A time table would have been an absurdity. "Go as you please" or "go as you can," was the order of the day. Passengers had rare opportunities for observation and discovery, and were frequently allowed pleasure excursions on shore while the boat was being cordelled over a rapid, was stranded on a bar, or waiting for wood to be cut and carried on board at some wooding station. Sometimes they were called upon to lend a helping hand at the capstan, or to tread the gang plank to a "wood up" quickstep. When on their pleasure excursion they strayed away too far, they were recalled to the boat by the firing of a gun or the ringing of a bell. It is doubtful if in later days, with all the improvements in steamboat travel, more enjoyable voyages have been made than these free and easy excursions in the light draught boats of the decades between 1830 and 1850, under such genial captains and officers as the Harrises, Atchinson, Throckmorton, Brasie, Ward, Blakeley, Lodwick, Munford, Pim, Orrin Smith and others.

Before the government had improved navigation the rapids of Rock Island and Des Moines, and snags, rocks and sandbars elsewhere were serious obstructions. The passengers endured the necessary delays from these causes with great good nature, and the tedium of the voyage was frequently enlivened by boat races with rival steamers. These passenger boats were then liberally patronized. The cost of a trip from St. Louis to St. Paul was frequently reduced to ten dollars, and considering the time spent in making the trip (often as much as two or three weeks) was cheaper than board in a good hotel, while the fare on the boat could not be excelled. The boats were frequently crowded with passengers, whole families were grouped about the tables or strolling on the upper decks, with groups of travelers representing all the professions and callings, travelers for pleasure and for business, explorers, artists, and adventurers. At night the brilliantly lighted cabin would resound with music, furnished by the boat's band of sable minstrels, and trembled to the tread of the dancers as much as to the throbbing of the engine.

The steamer, as the one means of communication with the distant world, as the bearer of mails, of provisions and articles of trade, was greeted at every village with eager and excited groups of people, some perhaps expecting the arrival of friends, while others were there to part with them. These were scenes to be remembered long, in fact many of the associations of river travel produced indelible impressions. In these days of rapid transit by rail more than half the delights of traveling are lost. Before the settlement of the country the wildness of the scene had a peculiar charm. The majestic bluffs with their rugged escarpments of limestone stretched away in solitary grandeur on either side of the river. The perpendicular crags crowning the bluffs seemed like ruined castles, some of them with rounded turrets and battlements, some even with arched portals. Along the slopes of the bluffs was a growth of sturdy oaks, in their general contour and arrangement resembling fruit trees, vast, solitary orchards in appearance, great enough to supply the world with fruit. On the slopes of the river bank might have been seen occasionally the bark wigwams of the Indian, and his birch canoe gliding silently under the shadow of the elms and willows lining the shore. Occasionally a deer would be seen grazing on some upland glade, or bounding away in terror at sight of the steamer.

A complete history of early steamboat navigation on the Upper Mississippi would abound with interesting narratives and incidents; but of these, unfortunately, there is no authentic record, and we can only speak in general terms of the various companies that successively controlled the trade and travel of the river, or were rivals for the patronage of the public. During the decade of the '30s, the Harrises, of Galena, ran several small boats from Galena to St. Louis, occasionally to Fort Snelling, or through the difficult current of the Wisconsin to Fort Winnebago, towing barges laden with supplies for the Wisconsin pineries. Capt. Scribe Harris' favorite boat from 1835 to 1838 was the Smelter. The captain greatly delighted in her speed, decorated her gaily with evergreens, and rounding to at landings, or meeting with other boats, fired a cannon from her prow to announce her imperial presence.

The Smelter and other boats run by the Harris family held the commerce of the river for many years. In 1846 the first daily line of steamers above St. Louis was established. These boats ran independently, but on stated days, from St. Louis to Galena and Dubuque. They were the Tempest, Capt. John J. Smith; War Eagle, Capt. Smith Harris; Prairie Bird, Capt. Niebe Wall; Monona, Capt. – Bersie; St. Croix, Capt. – ; Fortune, Capt. Mark Atchinson. These boat owners, with others, subsequently formed a consolidated company.

In 1847 a company was formed for the navigation of the Mississippi above Galena. The first boat in the line, the Argo, commanded by Russell Blakeley, was placed upon the river in 1846. The boats in this line were the Argo, Dr. Franklin, Senator, Nominee, Ben Campbell, War Eagle, and the Galena.

In 1854 the Galena & Minnesota Packet Company was formed by a consolidation of various interests. The company consisted of the following stockholders: O. Smith, the Harrises, James Carter, H. Corwith, B. H. Campbell, D. B. Morehouse, H. M. Rice, H. L. Dousman, H. H. Sibley, and Russell Blakeley. The boats of the new company were the War Eagle, Galena, Dr. Franklin, Nominee, and the West Newton. In 1857 a new company was formed, and the Dubuque boats, the Itasca and Key City, were added to the line. This line continued until 1862, and the new boats, Dr. Franklin, No. 2, and the New St. Paul, were added. The Galena had been burned at Red Wing in the fall of 1857.

The following is a list of the earliest arrivals at St. Paul after the opening of navigation between the years 1843 and 1858: April 5, 1843, steamer Otter, Capt. Harris; April 6, 1844, steamer Otter, Capt. Harris; April 6, 1845, steamer Otter, Capt. Harris; March 31, 1846, steamer Lynx, Capt. Atchison; April 7, 1847, steamer Cora, Capt. Throckmorton; April 7, 1848, steamer Senator, Capt. Harris; April 9, 1849, steamer Highland Mary, Capt. Atchison; April 19, 1850, steamer Highland Mary, Capt. Atchison; April 4, 1851, steamer Nominee, Capt. Smith; April 16, 1852, steamer Nominee, Capt. Smith; April 11, 1853, steamer West Newton, Capt. Harris; April 8, 1854, steamer Nominee, Capt. Blakeley; April 17, 1855, steamer War Eagle, Capt. Harris; April 18, 1856, steamer Lady Franklin, Capt. Lucas; May 1, 1857, steamer Galena, Capt. Laughton; March 25, 1858, steamer Gray Eagle, Capt. Harris.

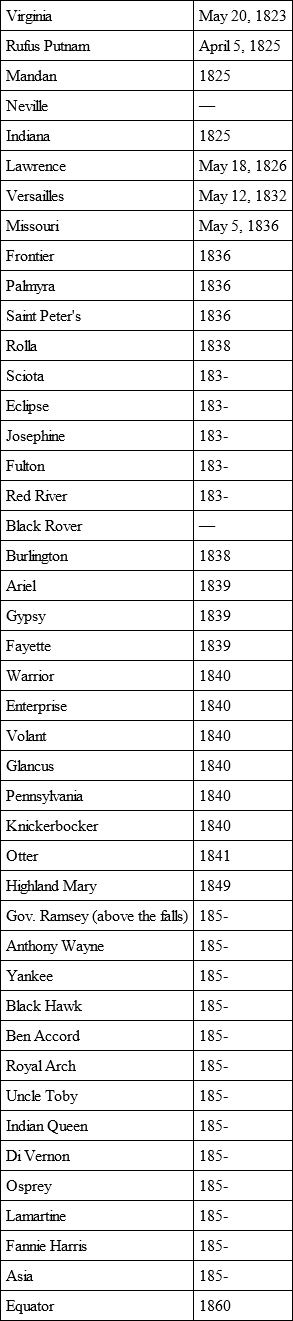

The following list includes boats not named in the packet and company lists with date of first appearance as far as can be ascertained:

The following made their appearance some time in the '40s: Cora, Lynx, Dr. Franklin, No. 2, and St. Anthony.

The Northern Line Company organized in 1857 and placed the following steamers upon the Mississippi, to run between St. Louis and St. Paul: The Canada, Capt. Ward; Pembina, Capt. Griffith; Denmark, Capt. Gray; Metropolitan, Capt. Rhodes; Lucy May, Capt. Jenks; Wm. L. Ewing, Capt. Green; Henry Clay, Capt. Campbell; Fred Lorenz, Capt. Parker; Northerner, Capt. Alvord; Minnesota Belle, Capt. Hill; Northern Light and York State, Capt. – .

Commodore W. F. Davidson commenced steamboating on the Upper Mississippi in 1856 with the Jacob Traber. In 1857 he added the Frank Steele, and included the Minnesota river in his field of operations. In 1859 he added the Æolian, Favorite and Winona. In 1860 he organized the La Crosse & Minnesota Packet Company, with the five above named steamers in the line. In 1862 the Keokuk and Northern Belle were added.

In 1864 the La Crosse & Minnesota and the Northern Line Packet companies were consolidated under the name of the Northwestern Union Packet Company, with the following steamers: The Moses McLellan, Ocean Wave, Itasca, Key City, Milwaukee City, Belle, War Eagle, Phil Sheridan, S. S. Merrill, Alex. Mitchell, City of St. Paul, Tom Jasper, Belle of La Crosse, City of Quincy, and John Kyle. This line controlled the general trade until 1874.

There were upon the river and its tributaries during the period named the following light draught boats: The Julia, Mollie Mohler, Cutter, Chippewa Falls, Mankato, Albany, Ariel, Stella Whipple, Isaac Gray, Morning Star, Antelope, Clara Hine, Geo. S. Weeks, Dexter, Damsel, Addie Johnson, Annie Johnson, G. H. Wilson, Flora, and Hudson.

LATER NAVIGATION ON THE UPPER MISSISSIPPI

The Northwestern Union Packet Company, more familiarly known as the "White Collar Line," from the white band painted around the upper part of the smokestacks, and the Keokuk Packet Company, sold their steamers to the Keokuk Northern Line Packet Company, which continued until 1882, when the St. Louis & St. Paul Packet Company was organized. Its boats were: The Minneapolis, Red Wing, Minnesota, Dubuque, Rock Island, Lake Superior, Muscatine, Clinton, Chas. Cheever, Dan Hine, Andy Johnson, Harry Johnson, Rob Roy, Lucy Bertram, Steven Bayard, War Eagle, Golden Eagle, Gem City, White Eagle, and Flying Eagle.

STEAMBOATING ON THE ST. CROIX

The steamer Palmyra was the first boat to disturb the solitude of the St. Croix. In June, 1838, it passed up the St. Croix lake and river as far as the Dalles. The steamer Ariel, the second boat, came as far as Marine in 1839. In the fall of 1843, the steamer Otter, Scribe Harris, commanding, landed at Stillwater. The steamer Otter was laden with irons and machinery for the first mill in Stillwater. Up to 1845 nearly every boat that ascended the Mississippi also ascended the St. Croix, but in later years, as larger boats were introduced, its navigation was restricted to smaller craft, and eventually to steamboats built for the special purpose of navigating the St. Croix. Quite a number of these were built at Osceola, Franconia and Taylor's Falls. The following is a list of boats navigating the St. Croix from the year 1852 to the present time: Humboldt, 1852; Enterprise, 1853; Pioneer, 1854; Osceola, 1854; H. S. Allen, 1857; Fanny Thornton, 1862; Viola, 1864; Dalles, 1866; Nellie Kent, 1867; G. B. Knapp, 1866; Minnie Will, 1867; Wyman X, 1868; Mark Bradley, 1869; Helen Mar, 1870; Maggie Reany, 1870; Jennie Hays, 1870; Cleon, 1870.

A number of raft steamers, built at South Stillwater and elsewhere, have plied the river within the last ten years. A number of barges were built at South Stillwater, Osceola and Taylor's Falls.

The passenger travel on the St. Croix has decreased since the completion of the railroad to Taylor's Falls and St. Croix Falls.

An interesting chapter of anecdotes and incidents might be compiled, illustrating the early steamboat life on the St. Croix. We find in "Bond's Minnesota" a notice of one of the first boats in the regular trade, which will throw some light on the subject of early travel on the river. It describes the Humboldt, which made its first appearance in 1852:

"In addition, some adventurous genius on a small scale, down about Oquaka, Illinois, last year conceived the good idea of procuring a steamboat suitable to perform the duties of a tri-weekly packet between Stillwater and Taylor's Falls, the extreme point of steam navigation up the St. Croix. It is true he did not appear to have a very correct idea of the kind of craft the people really wanted and would well support in that trade, but such as he thought and planned he late last season, brought forth. * * Indeed, the little Humboldt is a great accommodation to the people of the St. Croix. She stops anywhere along the river, to do any and all kinds of business that may offer, and will give passengers a longer ride, so far as time is concerned, for a dollar, than any other craft we ever traveled upon. She is also, to outward appearances, a temperance boat, and carries no cooking or table utensils. She stops at the 'Marine,' going and returning, to allow the people aboard to feed upon a good, substantial dinner; and the passengers are allowed, if they feel so disposed, to carry 'bars' in their side pockets and 'bricks' in their hats. A very accommodating craft is the Humboldt, and a convenience that is already set down on the St. Croix as one indispensable."

The Diamond Jo line of steamers was established in 1867. Jo Reynolds was president of the company and has served as such continuously to date. Under his general supervision the company has been quite successful. The business has required an average of six steamers yearly. In 1888 the line consists of the boats the Sidney, Pittsburgh and Mary Morton.

The St. Louis & St. Paul Packet Company, successors of the various old transportation companies, is in successful operation in 1888, employing three steamers. There are but few transient boats now on the river.

ICE BOATS

Several attempts have been made to navigate the river during the winter months by means of ice boats, but the efforts have uniformly failed. Of these attempts we mention the two most notable:

Noman Wiard, an inventor of some celebrity, made an ice boat in 1856 and placed it on the river at Prairie du Chien, intending to run between that point and St. Paul. It was elaborately planned and elegantly finished, and resembled somewhat a palace car mounted on steel runners. It failed on account of the roughness of the ice, never making a single trip. It, however, proved somewhat remunerative as a show, and was for some time on exhibition within an inclosure at Prairie du Chien.