полная версия

полная версияThe American Revolution

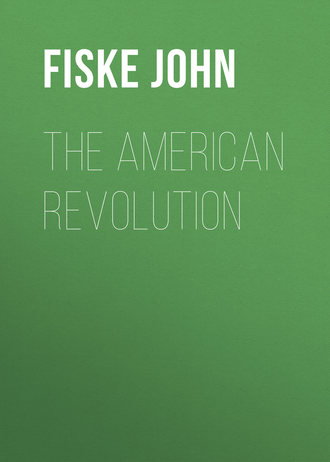

BOSTON, WITH ITS ENVIRONS, IN 1775 AND 1776

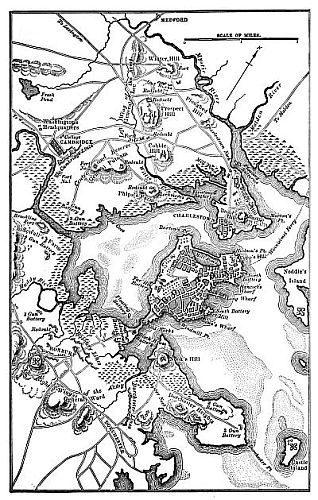

MEDAL GRANTED TO WASHINGTON FOR HIS CAPTURE OF BOSTON

Washington seizes Dorchester Heights March 4, 1776

Washington chose for his decisive movement the night of the 4th of March. Eight hundred men led the way, escorting the wagons laden with spades and crowbars, hatchets, hammers, and nails; and after them followed twelve hundred men, with three hundred ox-carts, carrying timbers and bales of hay; while the rear was brought up by the heavy siege-guns. From Somerville, East Cambridge, and Roxbury, a furious cannonade was begun soon after sunset and kept up through the night, completely absorbing the attention of the British, who kept up a lively fire in return. The roar of the cannon drowned every other sound for miles around, while all night long the two thousand Americans, having done their short march in perfect secrecy, were busily digging and building on Dorchester Heights, and dragging their siege-guns into position. Early next morning, Howe saw with astonishment what had been done, and began to realize his perilous situation. The commander of the fleet sent word that unless the Americans could be forthwith dislodged, he could not venture to keep his ships in the harbour. Most of the day was consumed in deciding what should be done, until at last Lord Percy was told to take three thousand men and storm the works. But the slaughter of Bunker Hill had taught its lesson so well that neither Percy nor his men had any stomach for such an enterprise. A violent storm, coming up toward nightfall, persuaded them to delay the attack till next day, and by that time it had become apparent to all that the American works, continually growing, had become impregnable. Percy’s orders were accordingly countermanded, and it was decided to abandon the town immediately. It was the sixth anniversary of the day on which Hutchinson had yielded to the demand of the town meeting and withdrawn the two British regiments from Boston. The work then begun was now consummated by Washington, and from that time forth the deliverance of Massachusetts was complete. Howe caused it at once to be known among the citizens that he was about to evacuate Boston, but he threatened to lay the town in ashes if his troops should be fired on.

The British troops evacuate Boston March 17, 1776The selectmen conveyed due information of all this to Washington, who accordingly, secure in the achievement of his purpose, allowed the enemy to depart in peace. By the 17th, the eight thousand troops were all on board their ships, and, taking with them all the Tory citizens, some nine hundred in number, they sailed away for Halifax. Their space did not permit them to carry away their heavy arms, and their retreat, slow as it was, bore marks of hurry and confusion. In taking possession of the town, Washington captured more than two hundred serviceable cannon, ten times more powder and ball than his army had ever seen before, and an immense quantity of muskets, gun-carriages, and military stores of every sort. Thus was New England set free by a single brilliant stroke, with very slight injury to private property, and with a total loss of not more than twenty lives.

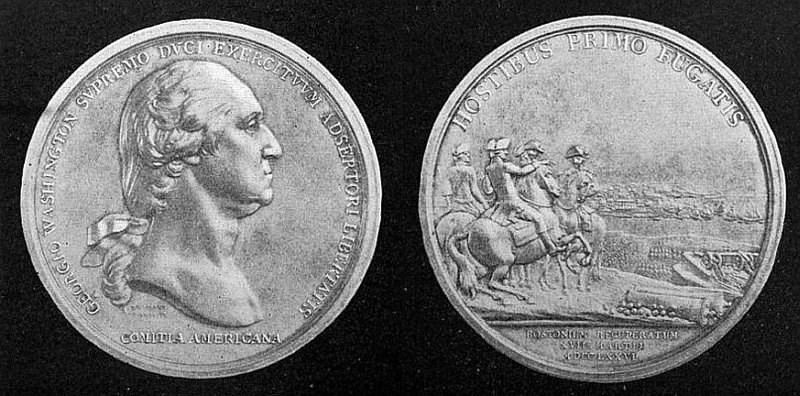

EVOLUTION OF THE UNITED STATES FLAG[8]

The time was now fairly ripe for the colonies to declare themselves independent of Great Britain. The idea of a separation from the mother-country, which in the autumn had found but few supporters, grew in favour day by day through the winter and spring.

A provisional flagThe incongruousness of the present situation was typified by the flag that Washington flung to the breeze on New Year’s Day at Cambridge, which was made up of thirteen stripes, to represent the United Colonies, but retained the British crosses in the corner. Thus far, said Benjamin Harrison, they had contrived to “hobble along under a fatal attachment to Great Britain,” but the time had come when one must consider the welfare of one’s own country first of all. As Samuel Adams said, their petitions had not been heard, and yet had been answered by armies and fleets, and by myrmidons hired from abroad.

Effect of the hiring of “myrmidons”Nothing had made a greater impression upon the American people than this hiring of German troops. It went farther than any other single cause to ripen their minds for the declaration of independence. Many now began to agree with the Massachusetts statesman; and while public opinion was in this malleable condition, there appeared a pamphlet which wrought a prodigious effect upon the people, mainly because it gave terse and vigorous expression to views which every one had already more than half formed for himself.

Thomas Paine had come over to America in December, 1774, and through the favour of Franklin had secured employment as editor of the “Pennsylvania Magazine.” He was by nature a dissenter and a revolutionist to the marrow of his bones. Full of the generous though often blind enthusiasm of the eighteenth century for the “rights of man,” he was no respecter of the established order, whether in church or state. To him the church and its doctrines meant slavish superstition, and the state meant tyranny. Of crude undisciplined mind, and little scholarship, yet endowed with native acuteness and sagacity, and with no mean power of expressing himself, Paine succeeded in making everybody read what he wrote, and achieved a popular reputation out of all proportion to his real merit. Among devout American families his name was for a long time a name of horror and opprobrium, and uneducated free thinkers still build lecture-halls in honour of his memory, and celebrate the anniversary of his birthday, with speeches full of harmless but rather dismal platitudes. The “Age of Reason,” which was the cause of all this blessing and banning, contains, amid much crude argument, some sound and sensible criticism, such as is often far exceeded in boldness in the books and sermons of Unitarian and Episcopalian divines of the present day; but its tone is coarse and dull, and with the improvement of popular education it is fast sinking into oblivion. There are times, however, when such caustic pamphleteers as Thomas Paine have their uses. There are times when they can bring about results which are not so easily achieved by men of finer mould and more subtle intelligence.

“Common Sense”It was at just such a time, in January, 1776, that Paine published his pamphlet, “Common Sense,” on the suggestion of Benjamin Rush, and with the approval of Franklin and of Samuel Adams. The pamphlet contains some irrelevant abuse of the English people, and resorts to such arguments as the denial of the English origin of the Americans. Not one third of the people, even of Pennsylvania, are of English descent, argues Paine, as if Pennsylvania had been preëminent among the colonies for its English blood, and not, as in reality, one of the least English of all the thirteen. But along with all this there was a sensible and striking statement of the practical state of the case between Great Britain and the colonies. The reasons were shrewdly and vividly set forth for looking upon reconciliation as hopeless, and for seizing the present moment to declare to the world what the logic of events was already fast making an accomplished fact. Only thus, it was urged, could the States of America pursue a coherent and well-defined policy, and preserve their dignity in the eyes of the world.

A PAGE FROM “COMMON SENSE”

See Transcription

Fulminations and counter-fulminations

It was difficult for the printers, with the clumsy presses of that day, to bring out copies of “Common Sense” fast enough to meet the demand for it. More than a hundred thousand copies were speedily sold, and it carried conviction wherever it went. At the same time, Parliament did its best to reinforce the argument by passing an act to close all American ports, and authorize the confiscation of all American ships and cargoes, as well as of such neutral vessels as might dare to trade with this proscribed people. And, as if this were not quite enough, a clause was added by which British commanders on the high seas were directed to impress the crews of such American ships as they might meet, and to compel them, under penalty of death, to enter the service against their fellow-countrymen. In reply to this edict, Congress, in March, ordered the ports of America to be thrown open to all nations; it issued letters of marque, and it advised all the colonies to disarm such Tories as should refuse to contribute to the common defence. These measures, as Franklin said, were virtually a declaration of war against Great Britain. But before taking the last irrevocable step, the prudent Congress waited for instructions from every one of the colonies.

The first colony to take decisive action in behalf of independence was North Carolina, a commonwealth in which the king had supposed the outlook to be especially favourable for the loyalist party. Recovered in some measure from the turbulence of its earlier days, North Carolina was fast becoming a prosperous community of small planters, and its population had increased so rapidly that it now ranked fourth among the colonies, immediately after Pennsylvania.

The Scots in North CarolinaSince the overthrow of the Pretender at Culloden there had been a great immigration of sturdy Scots from the western Highlands, in which the clans of Macdonald and Macleod were especially represented. The celebrated Flora Macdonald herself, the romantic woman who saved Charles Edward in 1746, had lately come over here and settled at Kingsborough with Allan Macdonald, her husband. These Scottish immigrants also helped to colonize the upland regions of South Carolina and Georgia, and they have considerably affected the race composition of the Southern people, forming an ancestry of which their descendants may well be proud. Though these Highland clansmen had taken part in the Stuart insurrection, they had become loyal enough to the government of George III., and it was now hoped that with their aid the colony might be firmly secured, and its neighbours on either side overawed.

Clinton sails for the CarolinasTo this end, in January, Sir Henry Clinton, taking with him 2,000 troops, left Boston and sailed for the Cape Fear river, while a force of seven regiments and ten ships-of-war, under Sir Peter Parker, was ordered from Ireland to coöperate with him. At the same time, Josiah Martin, the royal governor, who for safety had retired on board a British ship, carried on negotiations with the Highlanders, until a force of 1,600 men was raised, and, under command of Donald Macdonald, marched down toward the coast to welcome the arrival of Clinton.

The fight at Moore’s Creek, Feb. 27, 1776But North Carolina had its minute-men as well as Massachusetts, and no sooner was this movement perceived than Colonel Richard Caswell, with 1,000 militia, took up a strong position at the bridge over Moore’s Creek, which Macdonald was about to pass on his way to the coast. After a sharp fight of a half hour’s duration the Scots were seized with panic, and were utterly routed. Nine hundred prisoners, 2,000 stand of arms, and £15,000 in gold were the trophies of Caswell’s victory. The Scottish commander and his kinsman, the husband of Flora Macdonald, were taken and lodged in jail, and thus ended the sway of George III. over North Carolina. The effect of the victory was as contagious as that of Lexington had been in New England. Within ten days 10,000 militia were ready to withstand the enemy, so that Clinton, on his arrival, decided not to land, and stayed cruising about Albemarle Sound, waiting for the fleet under Parker, which did not appear on the scene until May.

North Carolina declares for independenceA provincial congress was forthwith assembled, and instructions were sent to the North Carolina delegates in the Continental Congress, empowering them “to concur with the delegates in the other colonies in declaring independency and forming foreign alliances, reserving to the colony the sole and exclusive right of forming a constitution and laws for it.”

Action of South Carolina and GeorgiaAt the same time that these things were taking place, the colony of South Carolina was framing for itself a new government, and on the 23d of March, without directly alluding to independence, it empowered its delegates to concur in any measure which might be deemed essential to the welfare of America. In Georgia the provincial congress, in choosing a new set of delegates to Philadelphia, authorized them to “join in any measure which they might think calculated for the common good.”

In Virginia the party in favour of independence had been in the minority, until, in November, 1775,

Virginia: Lord Dunmore’s proclamationthe royal governor, Lord Dunmore, had issued a proclamation, offering freedom to all such negroes and indented white servants as might enlist for the purpose of “reducing the colony to a proper sense of its duty.” This measure Lord Dunmore hoped would “oblige the rebels to disperse, in order to take care of their families and property.” But the object was not attained. The relations between master and slave in Virginia were so pleasant that the offer of freedom fell upon dull, uninterested ears.

With light work and generous fare, the condition of the Virginia negro was a happy one. The time had not yet come when he was liable to be torn from wife and children, to die of hardship in the cotton-fields and rice-swamps of the far South. He was proud of his connection with his master’s estate and family, and had nothing to gain by rebellion. As for the indented white servants, the governor’s proposal to them was of about as much consequence as a proclamation of Napoleon’s would have been if, in 1805, he had offered to set free the prisoners in Newgate on condition of their helping him to invade England. But, impotent as this measure of Lord Dunmore’s was, it served to enrage the people of Virginia, setting their minds irretrievably against the king and his cause. During the month of November, hearing that a party of “rebels” were on their way from North Carolina to take possession of Norfolk, Lord Dunmore built a rude fort at the Great Bridge over Elizabeth river, which commanded the southern approach to the town. At that time, Norfolk, with about 9,000 inhabitants, was the principal town in Virginia, and the commercial centre of the colony. The loyalist party, represented chiefly by Scottish merchants, was so strong there and so violent that many of the native Virginia families, finding it uncomfortable to stay in their homes, had gone away into the country.

Skirmish at the Great Bridge; and burning of NorfolkThe patriots, roused to anger by Dunmore’s proclamation, now resolved to capture Norfolk, and a party of sharpshooters, with whom the illustrious John Marshall served as lieutenant, occupied the bank of Elizabeth river, opposite Dunmore’s fort. On the 9th of December, after a sharp fight of fifteen minutes, in which Dunmore’s regulars lost sixty-one men, while not a single Virginian was slain, the fort was hastily abandoned, and the road to Norfolk was laid open for the patriots. A few days later the Virginians took possession of their town, while Dunmore sought refuge in the Liverpool, ship-of-the-line, which had just sailed into the harbour. On New Year’s Day the governor vindictively set fire to the town, which he had been unable to hold against its rightful owners. The conflagration, kindled by shells from the harbour, raged for three days and nights, until the whole town was laid in ashes, and the people were driven to seek such sorry shelter as might save them from the frosts of midwinter.

Virginia declares for independenceThis event went far toward determining the attitude of Virginia. In November the colony had not felt ready to comply with the recommendation of Congress, and frame for herself a new government. The people were not yet ready to sever the links which bound them to Great Britain. But bombardment of their principal town was an argument of which every one could appreciate the force and the meaning. During the winter and spring the revolutionary feeling waxed in strength daily. On the 6th of May, 1776, a convention was chosen to consider the question of independence. Mason, Henry, Pendleton, and the illustrious Madison took part in the discussion, and on the 14th it was unanimously voted to instruct the Virginia delegates in Congress “to propose to that respectable body to declare the United Colonies free and independent States,” and to “give the assent of the colony to measures to form foreign alliances and a confederation, provided the power of forming government for the internal regulations of each colony be left to the colonial legislatures.” At the same time, it was voted that the people of Virginia should establish a new government for their commonwealth. In the evening, when these decisions had been made known to the people of Williamsburgh, their exultation knew no bounds. While the air was musical with the ringing of church-bells, guns were fired, the British flag was hauled down at the State House, and the crosses and stripes hoisted in its place.

This decisive movement of the largest of the colonies was hailed throughout the country with eager delight; and from other colonies which had not yet committed themselves responses came quickly.

Action of Rhode Island and MassachusettsRhode Island, which had never parted with its original charter, did not need to form a new government, but it had already, on the 4th of May, omitted the king’s name from its public documents and sheriff’s writs, and had agreed to concur with any measures which Congress might see fit to adopt regarding the relations between England and America. In the course of the month of May town meetings were held throughout Massachusetts and it was everywhere unanimously voted to uphold Congress in the declaration of independence which it was now expected to make.

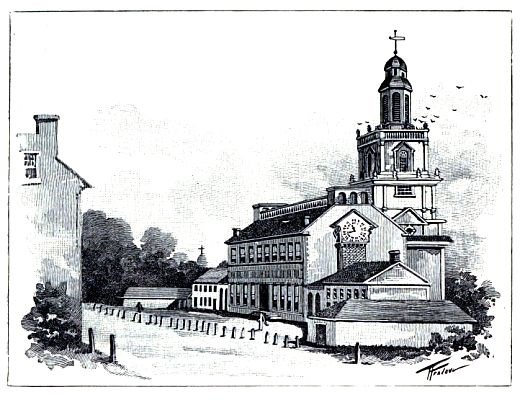

INDEPENDENCE HALL, PHILADELPHIA

Resolution of May 15

On the 15th of May, Congress adopted a resolution recommending to all the colonies to form for themselves independent governments, and in a preamble, written by John Adams, it was declared that the American people could no longer conscientiously take oath to support any government deriving its authority from the Crown; all such governments must now be suppressed, since the king had withdrawn his protection from the inhabitants of the United Colonies. Like the famous preamble to Townshend’s bill of 1767, this Adams preamble contained within itself the gist of the whole matter. To adopt it was virtually to cross the Rubicon, and it gave rise to a hot debate. James Duane of New York admitted that if the facts stated in the preamble should turn out to be true, there would not be a single voice against independence; but he could not yet believe that the American petitions were not destined to receive a favourable answer. “Why,” therefore, “all this haste? Why this urging? Why this driving?” James Wilson of Pennsylvania, one of the ablest of all the delegates in the revolutionary body, urged that Congress had not yet received sufficient authority from the people to justify it in taking so bold a step. The resolution was adopted, however, preamble and all; and now the affair came quickly to maturity. “The Gordian knot is cut at last!” exclaimed John Adams. In town meeting the people of Boston thus instructed their delegates: “The whole United Colonies are upon the verge of a glorious revolution. We have seen the petitions to the king rejected with disdain. For the prayer of peace he has tendered the sword; for liberty, chains; for safety, death. Loyalty to him is now treason to our country.

Instructions from BostonWe think it absolutely impracticable for these colonies to be ever again subject to or dependent upon Great Britain, without endangering the very existence of the state. Placing, however, unbounded confidence in the supreme council of the Congress, we are determined to wait, most patiently wait, till their wisdom shall dictate the necessity of making a declaration of independence. In case the Congress should think it necessary for the safety of the United Colonies to declare them independent of Great Britain, the inhabitants, with their lives and the remnant of their fortunes, will most cheerfully support them in the measure.”

Lee’s motion in CongressThis dignified and temperate expression of public opinion was published in a Philadelphia evening paper, on the 8th of June. On the preceding day in accordance with the instructions which had come from Virginia, the following motion had been submitted to Congress by Richard Henry Lee: —

“That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States; that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown; and that all political connection between them and the state of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

“That it is expedient forthwith to take the most effectual measures for forming foreign alliances.

“That a plan of confederation be prepared and transmitted to the respective colonies, for their consideration and approbation.”

In these trying times the two greatest colonies, Virginia and Massachusetts, had been wont to go hand in hand; and the motion of Richard Henry Lee was now promptly seconded by John Adams. It was resisted by Dickinson and Wilson of Pennsylvania, and by Robert Livingston of New York, on the ground that public opinion in the middle colonies was not yet ripe for supporting such a measure; at the same time these cautious members freely acknowledged that the lingering hope of an amicable settlement with Great Britain had come to be quite chimerical.

Debate on Lee’s motionThe prospect of securing European alliances was freely discussed. The supporters of the motion urged that a declaration of independence would be nothing more than the acknowledgment of a fact which existed already; and until this fact should be formally acknowledged, it was not to be supposed that diplomatic courtesy would allow such powers as France and Spain to treat with the Americans. On the other hand, the opponents of the motion argued that France and Spain were not likely to look with favour upon the rise of a great Protestant power in the western hemisphere, and that nothing would be easier than for these nations to make a bargain with England, whereby Canada might be restored to France and Florida to Spain, in return for military aid in putting down the rebellious colonies. The result of the whole discussion was decidedly in favour of a declaration of independence; but to avoid all appearance of undue haste, it was decided, on the motion of Edward Rutledge of South Carolina, to postpone the question for three weeks, and invite the judgment of those colonies which had not yet declared themselves.

Connecticut and New HampshireUnder these circumstances, the several colonies acted with a promptness that outstripped the expectations of Congress. Connecticut had no need of a new government, for, like Rhode Island, she had always kept the charter obtained from Lord Clarendon in 1662, she had always chosen her own governor, and had always been virtually independent of Great Britain. Nothing now was necessary but to omit the king’s name from legal documents and commercial papers, and to instruct her delegates in Congress to support Lee’s motion; and these things were done by the Connecticut legislature on the 14th of June. The very next day, New Hampshire, which had formed a new government as long ago as January, joined Connecticut in declaring for independence.

New JerseyIn New Jersey there was a sharp dispute. The royal governor, William Franklin, had a strong party in the colony; the assembly had lately instructed its delegates to vote against independence, and had resolved to send a separate petition to the king. Against so rash and dangerous a step, Dickinson, Jay, and Wythe were sent by Congress to remonstrate; and as the result of their intercession, the assembly, which yielded, was summarily prorogued by the governor. A provincial congress was at once chosen in its stead. On the 16th of June, the governor was arrested and sent to Connecticut for safe-keeping; on the 21st, it was voted to frame a new government; and on the 22d, a new set of delegates were elected to Congress, with instructions to support the declaration of independence.