полная версия

полная версияThe Man of Genius

174

Dialogues, i.

175

Dialogues, ii.

176

Bugeault, Étude sur l’état mental de Rousseau, 1876, p. 123.

177

Revue Philosophique, 1883.

178

Schurz, Lenaus Werke, vol. i. p. 275.

179

Kecskemetky, S. Széchénys staatsmänn. Laufbahn, &c., Pesth, 1866.

180

Costanzo, Follia anomale, Palermo, 1876.

181

Gwinner, Schopenhauers Leben, 1878; Ribot, La Philosophie de Schopenhauer, 1885; Carl von Sedlitz, Schopenhauer vom Medizinischen Standpunkt, Dorpat, 1872.

182

Gwinner, p. 26.

183

Memorabilien, ii. p. 332.

184

Parerga, ii. p. 38.

185

Pensiero e Meteore in Biblioteca Scientifica Internazionale, Milan, 1878; Azione degli Astri e delle Meteore sulla mente Umana, Milan, 1871.

186

Quetelet, Physique Sociale, Book iv. ch. i.

187

Mantegazza, op. cit.

188

E. Neville, Maine de Biran, Sa Vie, &c., p. 129, 1854.

189

Revue Bleue, 1888, No. 9.

190

Viaggio in Sicilia, vol. vii.

191

Epistolario, 1878.

192

Nature, Nov. 1883.

193

Réveillé-Parise, Physiologie des hommes livrés aux travaux de l’esprit, pp. 352-355.

194

Giussani, Vita, &c., p. 188.

195

Epistolario, p. 395.

196

Lebin, Sur l’époque de la composition de la Vita Nuova, p. 28.

197

Life and Letters, vol. i. p. 51.

198

Stopfer, Vie de Sterne, Paris, 1870.

199

Goethe, Aus Meinem Leben.

200

Zanolini, Rossini, 1876.

201

Clément, Les Musiciens Célèbres, Paris, 1878.

202

Alborghetti, Vita di Donizetti, 1876.

203

D’Este, Memorie su Canova, 1864.

204

Gotti, Vita di Michelangelo, Florence, 1873.

205

Milanesi, Lettere di Michelangelo, Florence, 1875.

206

Amoretti, Memorie storiche sulla vita e gli studi di Leonardo da Vinci, Milan, 1874.

207

W. Irving, Columbus, vol. i. p. 819; Roselly de Lorque, Vie de Colomb., 1857.

208

According to Secchi (Soleil, 1875) Scheiner preceded Galileo, and was himself preceded by Fabricio, though the discovery of this last was not known until a later date.

209

Galilei, Opere, vol. i. p. 69.

210

Arago, Œuvres, 1851.

211

Hœfer, op. cit.

212

Herschel, Outlines of Astronomy, 1874.

213

Arago, Notices Biographiques, 1855.

214

Atti, Della Vita di Malpighi, 1774.

215

Hœfer, Histoire de la Chimie, 1869.

216

Briefe an Schiller.

217

Gherardi, Rapporti sui Manoscritti di Galvani, 1839.

218

Schiaparelli, Intorno Alcune Lettere inedite di Lagrange, 1877.

219

Humboldt, Correspondance, Paris, 1868.

220

Letters from Humboldt to Varnhagen.

221

Arago, Notices Biographiques, 1855.

222

Whewell, History of the Inductive Sciences, 1857.

223

N. Bianchi, Vita di Matteucci, Florence, 1874.

224

The catalogue of small planets has been drawn from the Annuaire du Bureau des Longitudes (Paris, 1877-8). The list of comets has been taken from Carl’s Repertorium der Cometen Astronomie (Munich, 1864). It begins with the comet discovered by Hevelius in 1672, and ends with that found by Donati on the 23rd of July, 1864; Gambart’s comets, already separately enumerated, have been excluded. To keep the conditions analogous to those of the small planets, all the comets to which Carl does not assign a discoverer, have been omitted; this includes such as were expected from previous calculations or perceived with the naked eye by the general population. All those that were discovered simultaneously by several observers, unknown to one another, have, however, been included, for it is not a question of priority, but of the psychological moment of the discovery. Three comets discovered in the months of February, May, and December, were found in the southern hemisphere; they must, therefore, with reference to season be registered as for August, November, and June, and have so been counted.

225

Atti, Della Vita ed opere di Malpighi, Bologna, 1774.

226

History of Civilisation, i.

227

Études sur la Selection, &c., Paris, 1881.

228

Biographie Universelle des Musiciens, Paris, 1868-80.

229

Histoire des Musiciens Célèbres, Paris, 1878.

230

Dizionario dei Pittori, 1858.

231

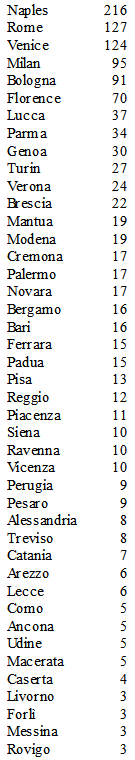

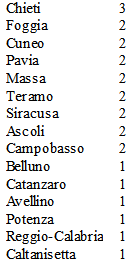

232

La Scuola Musicale di Napoli, 1883.

233

See my Pensiero e Meteore, 1872, and Archivio di Psichiatria, 1880, p. 157.

234

235

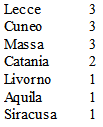

The difference with reference to painters is caused by the numerical weakness of Udine and the superiority of Catania and Palermo.

236

Il Censimento dei Poeti Veronesi, Dec. 31, 1881.

237

American Nervousness.

238

See Sternberg, Archivio di Psichiatria, vol. x. 1889, p. 389.

239

Statura degli Italiani, 1874; Della Influenza orografica nella Statura, 1878.

240

Étude sur la Taille.

241

Démographie de la France, 1878.

242

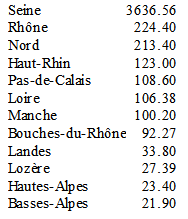

Inhabitants to the square kilomètre: —

243

“Les Antiquités Égyptiennes,” in Revue des Deux Mondes, April, 1865.

244

Archivio di Psichiatria, vol. viii. fasc. 3.

245

Libri, Histoire des Mathématiques, vol. iii.

246

De Candolle, Histoire des Sciences, 1873.

247

Joseph Jacobs, “The Comparative Distribution of Jewish Ability,” Journal of Anthropological Institute of Great Britain, 1886, pp. 351-379.

248

Gli Israeliti di Europa, 1872.

249

Archivio di Statistica, Rome, 1880.

250

Die Verbreit, der Blind, &c., 1872.

251

Renan in his Souvenirs de Jeunesse remarks that since Germany has given herself up to militarism she would have no men of genius, if it were not for the Jews, to whom she should be at least grateful. But he forgets Haeckel, Virchow, and Wagner.

252

One case is known in which parents zealously sought to educate and favour by every means poetic genius in their son. The outcome of their fervent efforts was Chapelain, the too famous singer of the Pucelle.

253

Hereditary Genius, 1868.

254

L’Hérédité Psychologique, 1878.

255

Biographie Universelle des Musiciens.

256

Ribot in his L’Hérédité Psychologique refers to French statistics of 1861 according to which in 1000 lunatics of each sex, there was hereditary influence in 264 men and in 266 women.

257

Galton himself remarks that of 31 great families of lawyers raised to the peerage before the end of the reign of George IV., twelve are extinct, especially those which contracted alliances with heiresses. Out of 487 families admitted to citizenship at Berne from 1583 to 1654 only 168 remained in 1783. “When a grandee of Spain is announced we expect to see an abortion” (Ribot, De l’Hérédité, p. 820). The French and Italian nobility to-day has become for the most part an inert instrument in the hands of the clergy. And how many of the sovereigns of Europe yet preserve those ancestral virtues to the presumed transmission of which they owe in large part their throne and prestige?

258

Dante, Purgatorio, canto vii.

259

Lucas, De l’Hérédité.

260

Ribot, L’Hérédité Psychologique.

261

Dugdale, The Jukes.

262

Académie des Sciences, 1871. Five cases of epilepsy, and of insanity, two of general paralysis, one of idiocy and several of microcephaly were observed under these circumstances. The microcephalic condition which so often appears among the hereditary results of alcoholism may be understood when we recall the atrophies, the cerebral scleroses (a kind of histologic microcephaly) which are so constantly found in the drunkard himself.

263

Bertolotti, Testamenti di Cardano, 1882.

264

De Vita Propria.

265

Famil XIII. 2, XXIII. 12.

266

Ireland, The Blot upon the Brain, 1885, p. 147; Déjerine, L’Hérédité dans les Maladies, 1886.

267

Bilder aus mein. Knabenzeit, 1837.

268

Memorie, p. 341. I.e., “The heads of the Taparelli are not in the right place.” Taparelli was a family name of D’Azeglio.

269

Souvenirs d’Enfance, p. 20.

270

Meynert, Jahresber. für Psychiatr., Vienna, 1880.

271

Ribot, L’Hérédité Psychologique, p. 171.

272

The same kind of influence may be traced among the insane and degenerate. A son of Louis XIV. and Madame de Montespan, conceived during a crisis of remorse and grief, at the epoch of the Jubilee, was called “l’enfant du jubilé,” on account of his condition of permanent melancholy. A man of talent, subject to attacks of mental exaltation, had several children, of whom two, conceived during these attacks, were insane. Déjerine, L’Hérédité dans les Maladies du Système Nerveux, 1886.

273

Nature, Nov., 1883.

274

Physiologie du Cerveau, p. 21.

275

Journal of Mental Science, 1872.

276

Correspondance Inédite, Paris, 1877.

277

Revue Scientifique, April, 1888.

278

Taine, Les origines de la France Contemporaine, Paris 1885.

279

Atlantic Monthly, 1881.

280

“A cui natura non lo volle direNol dirian mille Atēne e mille Rome.”281

E. Fournier, Le Vieux-Neuf, Paris, 1887.

282

Ch. Nodier, Les Bas bleus, 1846, p. 217.

283

Voyage en Italie, Paris, 1880.

284

Trélat, Recherches historiques sur la folie, p. 81. Paris, 1839.

285

Moreau, Psychologie morbide, Paris, 1859.

286

Marcé, “De la valeur des écrits des aliénés”; Journal de médecine mentale, 1864.

287

Leuret, Fragments psychologiques sur la folie.

288

Annales médico-psychologiques, tome iii. p. 93, 1864.

289

Annales médico-psychologiques, 1850, p. 48; Parchappe, Symptomatologie de la folie.

290

Tissot, Des nerfs et de leurs maladies, p. 133.

291

Médecine de l’esprit, vol. ii. p. 32.

292

Symptomotalogie de la folie.

293

J. Frank, Pathologie interne; Manie fantastique.

294

Traité des maladies mentales, 1858.

295

Revue Philosophique, 1888.

296

Esquiros, Paris au dix-neuvième siècle – Les maisons de fous, tome ii. p. 163.

297

See Appendix. I regret that in the English edition of my work it has not been found possible to give a more copious selection from the poems by the insane which I have at my disposal. For these I must refer the reader to the original Italian or to the French edition.

298

See my L’Uomo Delinquente.

299

Les prisons de Paris, 1881.

300

Diario del Manicomio di Pesaro, 1879.

301

Prescott, Conquest of Peru, i.

302

Lieut. – Col. Mark Wilks, Historical Sketch of the South of India.

303

Mungo Park, Travels, i.

304

Ellis, Polynesian Researches, vol. iv. p. 462, 1834.

305

La Paranoia, 1886.

306

Ludwig II.

307

P. Regnard, Les maladies épidémiques de l’esprit, p. 370.

308

Regnard, Les maladies, &c., p. 390.

309

Quoted by M. Luys, Actions réflexes du cerveau, p. 170

310

Revue Philosophique, 1888, No. 8.

311

Annales Med. Psych., 1876.

312

Regnard has also touched upon the subject, but without going into it deeply, in his Sorcellerie, Paris, 1887.

313

Gazzetta del Manicomio di Reggio, 1867.

314

O. Delepierre, Histoire littéraire des fous, Paris, 1860.

315

Regnard, op. cit.

316

Ruggieri, Histoire du crucifiement opéré sur sa propre personne par M. Lovat, Venice, 1806.

317

Frigerio, Letter of November 2, 1887.

318

Diario del Manicomio di Pesaro, 1879.

319

De Renzis, L’opera d’un pazzo, Rome, 1887.

320

Simon, Ann. Med. Psych., 1876.

321

Archivio di Psichiatria, 1880.

322

Steinthal, Entwicklung der Schrift, 1852.

323

Boddart, Palæography of America, London, 1865.

324

Lombroso, Uomo bianco ed uomo di colore, 1871.

325

Archivio di Psichiatria, 1881, fasc. iii.

326

“Un veleno ho preparatoDue pugnali tengo in seno:Questo viver disgraziatoFinirà una volta almenoT’amerò fino alla tombaE anche morto t’amerò.La campana lamentosaSonerà la morte mia,Ed allor tu udrai curiosaQuella funebre armonia.T’amerò, ecc. ecc.Una lunga e mesta croceNella via vedrai passar;Ed un prete sulla forcaMiserere recitar.T’amerò, ecc. ecc.”“I have prepared a poison; I have two daggers in my bosom; this unhappy life, at least, shall end one day. I will love thee to my grave, and even when dead, I will love thee still.

“The mournful bell shall sound for my death, and thou shall listen wonderingly to that funereal harmony. – I will love thee, &c.

“A long and sad cross (i. e., procession) thou shalt see passing along the road, and a priest standing by the gallows, reciting the Miserere. – I will love thee, &c.”

327

“Paranoia: A Study of the Evolution of Systematized Delusions of Grandeur,” in American Journal of Psychology, May, 1888, and May, 1889.

328

Hécart, op. cit.

329

Magnan.

330

Simon.

331

Delepierre.

332

Vasari, Vite dei pittori celebri.

333

Clément, Les musiciens célèbres, Paris, 1878.

334

“Voci alte e fioche e suon di man con elle” (Dante, Inf. iii. 27.)

335

Cato, De Re Rustica.

336

Essays, vol. ii. pp. 401, &c.

337

My attention was called many years ago to the frequent occurrence of insanity among great musicians by Dr. Arnaldo Bargoni, and afterwards by Mastriani, of Naples, in an excellent article in Roma, 1881.

338

Jasnot, Vérités positives, 1854.

339

Les fous littéraires, p. 51.

340

See Tre Tribuni, 1887.

341

“Always mistress or slave – a foe to thine own children.”342

“Il se trouvait là des philosophes plus forts que Leibnitz, mais sourdsmuets de naissance, ne pouvant produire que les gestes de leurs idées et pousser des arguments inarticulés; des peintres tourmentés de faire grand, mais qui posaient si singulièrement un homme sur ses pieds, un arbre sur ses racines, que toits leurs tableaux ressemblaient à des vues de tremblements de terre ou à des intérieurs de paquebots un jour de tempête. Des musiciens inventeurs de claviers intermédiaires, des savants à la façon du docteur Hitisch, de ces cervelles bric-à-brac, où il y a de tout mais où l’on ne trouve rien, à cause du désordre, de la poussière, et aussi parceque tous les objets sont cassés, incomplets, incapables du moindre service” (Daudet, Jack).

343

Delepierre, Littérateur des fous.

344

Staccar potessi i due concetti unitiDi me ed empio. Io giusto. Empio è Satana.345

Delepierre, op. cit.

346

“Lève ce chef d’ici, je crains que ce chef prive de chef les miens par un nouveau méchef.”

347

Philomneste, Les fous littéraires, 1881.

348

“Have you ever noticed,” writes Daudet (Jack, ii. 58), speaking of mattoids, whom he called les ratés, “how these people seek each other in Paris, how they are attracted to each other, how they group themselves with their grievances, their demands, their idle and barren vanities? While, in reality, full of mutual contempt, they form a Mutual Admiration Society, outside which the world is a blank to them.”

349

“Mais parmi ces groupes tapageurs qui s’en allaient frédonnant, déclamant, discutant encore, personne ne prenait garde au froid sinistre de la nuit ni au brouillard humide qui tombait. A l’entrée de l’avenue, on s’aperçut que l’heure des omnibus était passée. Tous ces pauvres diables en prirent bravement leur parti. La chimére aux écailles d’or éclairait et abrégeait leur route, l’illusion leur tenait chaud, et répandus dans Paris désert, ils se tournaient courageusement aux misères obscures de la vie.

“L’art est un si grand magicien! Il crée un soleil qui luit pour tous comme l’autre, et ceux qui s’en approchent, même les pauvres, même les laides, même les grotesques, emportent un peu de sa chaleur et de son rayonnement. Ce feu du ciel imprudemment ravi, que les ratés gardent au fond de leurs prunelles, les rend quelquefois redoutables, le plus souvent ridicules, mais leur existence en reçoit une sérénité grandiose, un mépris du mal, une grâce à souffrir que les autres misères ne connaissent pas” (Daudet, Jack, i. p. 3).

350

“Toute une littérature est née de mon Insecte et de mon Oiseau. —L’Amour et la Femme restent et resteront, comme ayant deux bases, l’une scientifique, la nature même, – l’autre morale, le cœur des citoyens…

“J’ai défini l’histoire une résurrection. – C’est le titre le plus approprié à mon 4 volumes…

“En 1870, dans le silence universel, seul, je parlai. Mon livre fait en 40 jours fut la seule défense de la patrie…”

351

He studies, as an important document, the journal of Louis XIV.’s digestion, and divides his reign into two periods – before and after the fistula. In the same way Francis I.’s reign is divided into the periods before and after the abscess. Conclusions of the following kind abound: —

“De toute l’ancienne monarchie, il ne reste à la France qu’un nom, Henri IV.; et deux chansons Gabrielle et Marlborough.”