полная версия

полная версияThe Man of Genius

The frequency of genius among lunatics and of madmen among men of genius, explains the fact that the destiny of nations has often been in the hands of the insane; and shows how the latter have been able to contribute so much to the progress of mankind.

In short, by these analogies, and coincidences between the phenomena of genius and mental aberration, it seems as though nature had intended to teach us respect for the supreme misfortunes of insanity; and also to preserve us from being dazzled by the brilliancy of those men of genius who might well be compared, not to the planets which keep their appointed orbits, but to falling stars, lost and dispersed over the crust of the earth.

APPENDIX.

POETRY AND THE INSANE

The following letter was written by a druggist confined in the Asylum of Sainte-Anne: —

Sainte-Anne, le 26 février 1880.Madame,Veuillez agréer l’hommageDe ce modeste sonnetEt le tenir comme un gageDe mon sincère respect.SonnetSouvenez-vous, reine des dieux,Vierge des vierges, notre mère,Que vous êtes sur cette terreL’ange gardien mystérieux.485The same man addressed to M. Magnan a long poem on a dramatic representation accompanied by the following graceful envoi: —

Vénéré Docteur,L’estime et la reconnaissanceSont la seule monnaie du cœurDont votre pauvre serviteurDispose pour la récompenseQu’il doit à vos soins pleins d’honneur.Recevez donc cet humble hommage,Docteur admiré, révéré,Et j’ajouterai bien-aimé,Si vous vouliez tenir pour gageQu’en cela du moins J’AI PAYE.486The following lines are from a long satirical poem by a writer who appears to have cherished much less respect for his physician. He believed that he had been changed into a beast, and recognised a colleague in every horse or donkey he met. He wished to browse in every field, and only refrained from doing so out of consideration for his friends: —

Les médicastres sans vergogneQui changent en sale besogneLe plus sublime des mandats,Ces infâmes aliénistes,Qui, reconnus pour moralistes,Sont les pires des scélérats!Ils détruisent les écrituresPour maintenir les imposturesDes ennemis du bien public.Ils prostituent leur justicePour se gorger du bénéficeDe leur satanique trafic.487The author of the following lines on the same day made an attempt at suicide, and then a homicidal attack on his mother.

À Monsieur le Docteur CÉPITRE (13 mai 1887)Un docteur éminent sollicite ma muse.Certes l’honneur est grand; mais le docteur s’amuse,Car, dans ce noir séjour, le poète attristéPar le souffle divin n’est guère visité…Faire des vers ici, quelle rude besogne!On pourra m’objecter que jadis, en Gascogne,Les rayons éclatants d’un soleil du MidiRéveillaient quelquefois mon esprit engourdi;Il est vrai: dans Bordeaux, cité fière et polie,J’ai fêté le bon vin, j’ai chanté la folie,Celle bien entendu qui porte des grelots.Mais depuis, un destin fatal à mon reposM’exile loin des bords de la belle Gironde,Qu’enrichissent les vins les plus fameux du monde!Aussi plus de chansons, de madrigaux coquets!Plus de sonnets savants, de bacchiques couplets!Ma muse tout en pleurs a replié ses ailes,Comme un ange banni des sphères éternelles!Dans sa cage enfermé l’oiseau n’a plus de voix…Hélas! je ne suis point le rossignol des bois,Pas même le pinson, pas même la fauvette;Vous me flattez, docteur, en m’appelant poète…Je ne suis qu’un méchant rimeur, et je ne saisSi ces alexandrins auront un grand succès…Cependant mon désir est de vous satisfaire;Votre estime m’honore et je voudrais vous plaire,Mais Pégase est rétif quand il est enchaîné;D’un captif en naissant le vers meurt condamné.Si vous voulez, docteur, que ma muse renaisse,Je ne vous dirai pas: rendez-moi ma jeunesse.Non, mais puisque vos soins m’ont rendu la santé,Ne pourriez-vous me rendre aussi la liberté?Des vers! Pour que le ciel au poète en envoieQue faut-il? le grand air, le soleil et la joie!Accordez-moi ces biens: mon luth reconnaissant,Pour vous remercier comme un Dieu bienfaisant,Peut-être trouvera, de mon cœur interprète,Des chants dignes de vous, et dignes d’un poète!The following lines well express the solitary sadness of the melancholiac: —

A Se StessoE con chi l’hai?Con tutti e con nessuno,L’ho con il cielo, che si tinge a bruno,L’ho con il metro, che non rende i lai,Che mi rodono il petto.Nell’odio altrui, nel mal comun mi godo.And these are of marvellous delicacy and truth: —

Tipo Fisico-Morale di P. LQUI RICOVERATOAl primo aspettoChi ti vede, sariaCostretto a dir che a te manca l’affetto;E male s’apporria;Che invece spesse fiate,Sotto ruvido vel, palpitan leneL’anime innamorateChe s’accendon, riscaldansi nel bene.Così rosa dal petaloInvisibile quasiMette l’effluvio dai raccolti vasi,Come dal gelsomino,E i delicati odor dell’amorino;Nemico a tutti i giuochi,Di Venere, di Bacco indarno i fuochiTi soffiano; la cuteE di tal forza che sembrano muteLe vezzose lusinghe …E invano a darti il fiato spira l’etra.M. S.The following little piece is a masterpiece of insane poetry: —

A un Uccello del CortileDa un virgulto ad uno scoglioDa uno scoglio a una collina,L’ala tua va pellegrinaVoli o posi a notte e dì.Noi confitti al nostro orgoglio,Come ruote in ferrei perni,Ci stanchiamo in giri eterni,Sempre erranti e sempre qui!Cavaliere Y.1

Magnan, Annales Médico-Psychologiques, 1887; Lombroso, Tre Tribuni, pp. 3-9, 16-23, 148-150; Saury, Études Cliniques sur la Folie Héréditaire, 1886.

2

Psychologie du Génie, 1883.

3

De Renzis, L’opera d’un Pazzo, 1887.

4

Revue des Deux Mondes, 1886.

5

De Pronost., i. p. 7.

6

Problemata, sect. xxx.

7

Horace, Ars Poet., 296-297.

8

Observationes in Hom. Affect., 1641, lib. 10, p. 305. More singular examples in Italy were collected by F. Gazoni, in the Hospitale dei folli incurabili, 1620.

9

Diderot, Dictionnaire Encyclopédique.

10

I Mattoidi e il Monumente a Vittorio Emanuele, 1885.

11

Magnan, Annales Médico-psych., 1887; Déjerine, L’Hérédité dans les Maladies Mentales, 1886; Ireland, The Blot upon the Brain, 1885.

12

I Caratteri dei Delinquenti, 1886, Turin.

13

Méd. de l’Esprit, ii.

14

Lamartine, Cours de Littérature, ii.

15

Revue Britannique, 1884.

16

Canesterini, Il Cranio di Fusinieri, 1875.

17

Plutarch, Life of Pericles, iii.

18

Kupfer, “Der Schädel Kants,” in Arch. für Anth., 1881.

19

Welcker, Schiller’s Schädel, 1883.

20

Mantegazza, Sul Cranio di Foscolo, Florence, 1880.

21

Turner, Quarterly Journal of Science, 1864.

22

De Quatrefages, Crania Ethnica, Part i. p. 30.

23

Zoja, La Testa di Scarpa, 1880.

24

Sul Cranio di Volta, 1879, Turin.

25

Welcker, Schiller’s Schädel, 1883.

26

Revue Scientifique, 1882.

27

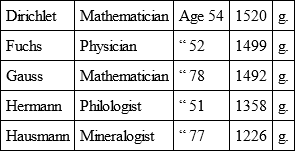

Wagner (Das Hirngewicht, 1877) gives these measurements of scientific men of Gottingen: —

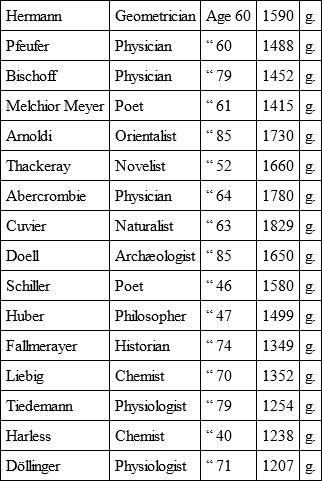

Bischoff (Hirngewichte bei Münchener Gelehrten) gives the following measurements: —

The measurement of the cerebral area often gives superiority even to those men of genius who present a feeble weight. Fuchs had a cerebral surface of 22,1005 square c. and Gauss of 21,9588; while with the same weight the same surface in an unknown woman was 20,4115 and in a workman 18,7672.

28

Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie, 1861.

29

Die tiefen Windungen des Menschenhirnes, 1877.

30

Mendel, Centralblatt, No. 4, 1884.

31

Ein Beitrag zur Anatomie der Affenspalte und der Interparietal Furche beim Menschen nach Rasse, Geschlecht, und Individualität, 1886.

32

Bulletin de la Société d’Anthropologie, 1886, p. 135.

33

La Circonvolution de Broca, Paris, 1888.

34

Vorstudien, &c., 1st Memoir, 1860.

35

Le Cerveau et la Pensée, t. ii. p. 46.

36

Gallichon in Gazette des Beaux Arts, 1867.

37

Lombroso, Sul Mancinismo motorio e sensorio nei sani e negli alienati, 1885, Turin.

38

Essay VII., Of Parents and Children.

39

Lettres à Georges Sand, Paris, 1885.

40

Destouches, Philos. Mariés.

41

Beard, American Nervousness, 1887; Cancellieri, Intorno Uomini dotati di gran memoria, 1715; Klefeker, Biblioth. eruditorum procacium, Hamburg, 1717; Baillet, De præcocibus eruditis, 1715.

42

Savage, Moral Insanity, 1886.

43

Guy de Maupassant, Étude sur Gustave Flaubert, Paris, 1885.

44

Revue des Deux Mondes, 1883, p. 92.

45

Revue Bleue, 1887, p. 17.

46

Darwin’s Life, 1887.

47

Genie und Talent.

48

Fischer, Æsthetik, ii. 1, p. 386.

49

“I am one who, when Love inspires, attend, and according as he speaks within me, so I express myself.”

50

Schilling, Psychiat. Briefe, p. 486.

51

Ball, Leçons des Maladies Mentales, 1881.

52

Radestock, p. 42.

53

Apologia.

54

Letter of April 20, 1752.

55

Verga, Lazzaretti, 1880.

56

Réveillé-Parise, p. 285.

57

Arago, Œuvres, iii.

58

Kreislauf des Lebens, Brief. xviii.

59

Dilthey, Ueber Einbildungskraft der Dichter, 1887.

60

Lazzaretti, op. cit., 1880.

61

Des Hallucinations, p. 30. Recent investigations in hypnotism show that the hallucination often has the character of real sensation; that, for example, visual suggestions may be modified by lenses. See my Nuove Studii sull’ ipnotismo.

62

Studi Critici, Naples, 1880, p. 95.

63

Souvenirs, p. 73, Paris, 1883.

64

Confessions d’un Enfant du Siècle, pp. 218, 251.

65

Introduction to Essai sur les Mœurs.

66

Siècle de Louis XIV., 1.

67

Dictionnaire Philosophique, art. Climat.

68

Tagebuch, ii. p. 120.

69

Paradoxe sur le Comédien.

70

Noise had become an obsession to Jules de Goncourt, says his brother Edmund, in a note to the former’s Lettres: “It seemed to him that he had ‘an ear in the pit of his stomach,’ and indeed noise had taken, and continued to take as his illness increased, as it were in some féerie at once absurd and fatal, the character of a persecution of the things and surroundings of his life… During the last years of his life he suffered from noise as from a brutal physical touch… This persecution by noise led my brother to sketch a gloomy story during his nightly insomnia… In this story a man was eternally pursued by noise, and leaves the rooms he had rented, the houses he had bought, the forests in which he had camped, forests like Fontainebleau, from which he is driven by the hunter’s horn, the interior of the pyramids, in which he was deafened by the crickets, always seeking silence, and at last killing himself for the sake of the silence of supreme repose, and not finding it then, for the noise of the worms in his grave prevented him from sleeping. Oh, noise, noise, noise! I can no longer bear to hear the birds. I begin to cry to them like Débureau to the nightingale, ‘Will you not be still, vile beast?’ ” (Lettres de Jules de Goncourt, Paris, 1885.)

71

Étude sur Gustave Flaubert, Paris, 1885.

72

Among the fragments that have been preserved some are of great sweetness: —

“Quanto fu dolce il giogo e la catenaDe’ suoi candidi bracci al col mio volte,Che sciogliendomi io sento mortal pena;D’altre cose non dico che son molte,Chè soverchia dolcezza a morte mena.”73

Mantegazza, Del Nervosismo dei grandi uomini, 1881.

74

Journal des Savants, Oct., 1863.

75

Epistolario, v. 3, p. 163.

76

Vicq d’Azir, Elog., p. 209.

77

Physiologie des Génies, 1875.

78

Science et Matérialisme, 1890, p. 103.

79

Brewster, Life, 1856.

80

Revue Scientifique, 1888.

81

Michiels, Le Monde du Comique, 1886.

82

Réveillé-Parise, op. cit.

83

Perez, L’enfant de trois à sept ans, 1886.

84

Scherer, Diderot, 1880.

85

Ueber die Verwandtschaft des Genies mit dem Irrsinn, 1887.

86

Bertolotti, Il Testamento di Cardano, 1883.

87

G. Flaubert, Lettres à Georges Sand, Paris, 1885.

88

Delepierre, Histoire Littéraire des fous, Paris, 1860.

89

Réveillé-Parise, Physiologie et Hygiène des hommes livrés aux travaux de l’esprit, Paris, 1856.

90

Mantegazza, Physiognomy and Expression.

91

Arago, ii. p. 82.

92

Plutarch, Life, &c.

93

Radestock, op. cit.

94

Moreau, op. cit., p. 523.

95

Correspondance, p. 119, 1887.

96

Memorie dell Istituto Lombardo, 1878.

97

Letter to Giordani, Aug., 1817.

98

Sette Anni di Sodalizio.

99

B. de Boismont, op. cit. p. 265.

100

Hagen, Ueber die Verwandtschaft, &c., 1877.

101

Roger, Voltaire Malade, 1883.

102

G. Sand, Histoire de Ma Vie, 9.

103

Berti, p. 154.

104

Berti, Cavour Avanti il 1848, Rome; Mayor, in Archivo di Psichiatria, vol. iv.

105

Mayor, op. cit.

106

Autobiography.

107

Autobiography, p. 145.

108

Von Sedlitz, Schopenhauer, 1872.

109

Letters, 1885.

110

Histoire de Ma Vie, v. p. 9.

111

G. Sand, op. cit.

112

De Immenso et innumerat., iii.

113

G. Menke, De ciarlataneria eruditorum, 1780.

114

Revue des Deux Mondes, 1883.

115

Letters, p. 62.

116

Ibid., pp. 62, 119, 123.

117

G. Sforza, Epistolario di A. Manzoni, Milan, 1883.

118

Epistolario, 3, p. 163.

119

Correspondance, p. 119. 1887.

120

Journal de ma vie intime.

121

Souvenirs d’Enfance et de Jeunesse.

122

Amiel, Journal Intime, Geneva, 2nd ed., 1889.

123

Clément, Musiciens célèbres, Paris, 1868.

124

W. Irving, Life, 1880.

125

Verga, Lazzaretti,&c., Milan, 1880.

126

Forbes Winslow, op. cit., p. 123.

127

Forbes Winslow, op. cit., p. 126.

128

Works, vol. xxvi. p. 83.

129

Dendy, op. cit., p. 41.

130

Correspondance, vol. ii. letter 9.

131

De Factis Dictisque Memorabilibus, Lib. vi. Cap. 9.

132

Tertullian, Apologetica, p. 46. But see A. Gellii Noctes Atticæ, x. p. 17.

133

Wiederbelebung des Klassisch, Altert., 1882.

134

Pouchet, Histoire des Sciences Naturelles dans le Moyen Age, 1870.

135

Masi, La vita ed i tempi di Albergati, 1882.

136

Laura had eleven children and Petrarch himself two when he dedicated to her 294 sonnets. In politics he turned from Cola di Rienzi to his enemy Colonna and from Robert to Charles IV. (Famil, xix. 1. p. 32). He was too much occupied with himself, says Perrens, to be occupied with his country.

137

Lettres à G. Sand, 1885.

138

Revue Philosophique, 1887, p. 69.

139

Confessions d’un Enfant du Siècle, pp. 250, 251.

140

Cottrau, Lettre d’un Mélomane, Naples, 1885.

141

Matthew x. 34-36; Luke xii. 51-53.

142

Luke xii. 49. See the Greek text.

143

Luke xviii. 29-30.

144

Luke xiv. 26.

145

Matthew x. 37, xvi. 24; Luke v. 23.

146

Matthew viii. 21; Luke v. 23.

147

Fiorentino, La Musica, Rome, 1884.

148

L’Uomo Delinquente, 1889.

149

Mastriani, Sul Genio e la Follia, Naples, 1881.

150

Tra un Sigaro e l’altro, p. 194.

151

Max. du Camp, Souvenirs, 1884.

152

Schilling, Psychiatr. Briefe., p. 488, 1863.

153

Zimmermann, Solitude.

154

Tagebuch, 1787, Berne.

155

Sketches of Bedlam, 1823.

156

Biographie, by Wasielewski, Dresden, 1858.

157

Maxime du Camp, Souvenirs littéraires, 1887.

158

Brunetière, Revue des Deux Mondes, 1887, No. 706. Revue Bleue, July, 1887.

159

Maxime du Camp, Souvenirs littéraires.

160

“A une Heure du Matin,” in Petits Poèmes en Prose.

161

Bufalini, Vita di Concato, 1884.

162

Revue Philosophique, 1886.

163

Littré, A. Comte et la Phil. Posit., 1863.

164

W. de Fonvielle, Comment se font les Miracles, 1879.

165

De Vita propria, ch. 45.

166

Byron said, also, that intermittent fevers came at last to be agreeable to him, on account of the pleasant sensation that followed the cessation of pain.

167

“One day I thought I heard very sweet harmonies in a dream. I awoke, and I found I had resolved the question of fevers: why some are lethal and others not – a question which had troubled me for twenty-five years” (De Somniis, c. iv.).

“In a dream there came to me the suggestion to write this book, divided into exactly twenty-one parts; and I experienced such pleasure in my condition and in the subtlety of these reasonings as I had never experienced before” (De Subtilitate, lib. xviii. p. 915).

168

“Jewels in sleep are symbolical of sons, of unexpected things, of joy also; because in Italian gioire means ‘to enjoy’ (De Somniis, cap. 21; De Subtilitate, p. 338).

169

Buttrini, Girolamo Cardano, Savona, 1884.

170

Bertolotti (I Testamenti di Cardano, 1888) has shown that this legend has no foundation.

171

“I shall live in the midst of my torments, and among the cares that are my just furies, wild and wandering; I shall fear dark and solitary shades, which will bring before me my first fault; and I shall have in horror and disgust the face of the sun which discovered my misfortunes; I shall fear myself, and, for ever fleeing from myself, I shall never escape.”

172

Brewster’s Memoirs of Sir I. Newton, vol. ii. p. 100.

173

Brewster’s Memoirs of Sir I. Newton, vol. ii. p. 94.