полная версия

полная версияThe Man of Genius

What could be more natural than that, in the conditions in which the emotions are most energetic, and so frequently atavistic, as is the case in insanity, these tendencies should be reproduced on a larger scale?

This, too, explains why so many morbid men of genius should be musicians: Mozart, Schumann, Beethoven, Donizetti, Pergolese, Fenicia, Ricci, Rocchi, Rousseau, Handel, Dussek, Hoffmann, Glück, Petrella.337 Musical creation is the most subjective manifestation of thought, the one most intimately connected with the affective emotions, and having less relation to the external world than any other, which causes it to stand more in need of the fervent but exhausting emotions of inspiration.

Perhaps the study of these peculiarities of art in the insane, besides showing us a new phase in this mysterious disease, might be useful in æsthetics, or at any rate in art-criticism, by showing that an exaggerated predilection for symbols, and for minuteness of detail (however accurate), the complication of inscriptions, the excessive prominence given to any one colour (it is well known that some of our foremost painters are great sinners in this respect), the choice of licentious subjects, and even an exaggerated degree of originality, are points which belong to the pathology of art.

CHAPTER III.

Literary and Artistic Mattoids

Definition – Physical and psychical characteristics – Their literary activity – Examples – Lawsuit mania – Mattoids of genius – Bosisio – The décadent poets – Verlaine – Mattoids in art.

WE have just been considering, in madmen, the substantial character of genius under the appearance of insanity. There is, however, a variety of these, which permits the appearance of genius and the substantial character of the average man; and this variety forms the link between madmen of genius, the sane, and the insane properly so called. These are what I call semi-insane persons or mattoids.

This variety constitutes, in the world of mental pathology, a particular species of a genus distinguished by Maudsley as “odd, queer, strange” persons of insane temperament, and previously by Morel. Legrand du Saulle, and Schüle (Geisteskrankheit, ii., 1880) regard them as hereditary neurotics, Raggi as neuropathics, and now many as paranoiacs– a terminology which produces a hopeless confusion.

The graphomaniac, representing the commonest variety, has true negative characteristics – that is to say, the features and cranial form are nearly always normal (Bosisio, Cianchettini, F – , P – , &c.). His characteristics are not the result of heredity; at most, he is the son of a man of genius (Flourens, Broussais, Spandri, Knester, &c.). This form of aberration is most frequently found in men; I only know of one exception in Europe – Louise Michel – and it appears more especially in great cities, worn out with civilization. The mattoid shows far fewer signs of degeneracy than the insane properly so called: – Of 33 mattoids only 21 showed degenerative characters, and of these last 12 had 2, 2 were found to have 3, there were 2 with 4, and only 1 with 6.

Another negative characteristic is the survival of family affection, and even of that for the human race in general, sometimes reaching such a point as to become exaggerated altruism; though, in many cases, vanity enters largely into the composition of this virtue. Thus Bosisio thinks of and provides for the well-being of posterity, and even of the dead. Thus D – loves his wife and grandchildren, and constantly works for his family; Cianchettini supported a deaf and dumb sister; Sbarbaro, Lazzaretti, Coccapieller, adored their wives.

In prison, a few days ago, I had occasion to perform the operation of blood-transfusion, and wasted much time in trying to find a healthy individual from whom to take the blood. All refused; but a consumptive mattoid, as soon as he heard of the matter, volunteered for the operation, and was overwhelmed with shame when I would not make use of him.

They have an exaggerated conviction of their own personal merit and importance, with the peculiar characteristic that this opinion shows itself rather in writing than in words or actions, so that they do not show irritation at the contradictions and evils of practical life.

Cianchettini compares himself to Galileo and to Jesus Christ; but sweeps the barrack-stairs. Passanante proclaims himself President of the Political Society while working as a cook. Mangione classified himself as a martyr to Italy and to his own genius; yet he condescended to act as a broker. Caissant claimed to be a cardinal, but, in the meantime, he was a clever parasite, and made large profits through his very insanity. The shepherd Bluet believed himself to be an apostle and count of Permission, and, like the author of Scottatinge, deigned to address himself to none but royal personages. Yet he did not refuse to carry on the trade of a horse-breaker.

Stewart, the eccentric author of the New System of Physical Philosophy, who travelled all over the world to discover the polarity of truth, asserted that all the kings of the earth had entered into an alliance to destroy his works. He therefore gave the latter to his friends, with the request to wrap them up well, and bury them in remote localities, – never revealing the latter, except on their death-beds. Martin Williams – brother of that Jonathan Williams, who, in an attack of insanity, set fire to York Minster, and of John Williams who struck out a new line in painting – published many works to prove the theory of perpetual motion. After having convinced himself by means of thirty-six experiments of the impossibility of demonstrating it scientifically, it was revealed to him in a dream that God had chosen him to discover the great cause of all things, and perpetual motion; and this he made the subject of many works.338

These persons would not come under the heading of mattoids, if, in their writings, the earnestness and persistence in one idea which make them resemble the monomaniac and the man of genius, were not often associated with the pursuit of absurdity, continual contradictions, and the prolixity and utility of insanity. One tendency overpowers all others – one which we find predominant in insane genius: viz., personal vanity. Thus, out of 215 mattoids, we find forty-four prophets.

Filopanti, in the Dio Liberale, places his father Berillo, a carpenter, and his mother Berilla among the demigods. He discovered three Adams, and gives a minute narrative, year by year, of the actions of each. Cordigliani prepared to insult the Chamber of Deputies in order to obtain an annuity from the Government, and thought this action much to his own credit. Guiteau thought he was saving the Republic by the murder of the President, and had himself called a great lawyer and philosopher. In the same way Passanante, after having preached the abolition of capital punishment, condemns the guilty members of the Assembly to death; and, after having given orders to “respect the forms of government,” insults the monarchy, makes an attempt at regicide, and proposes to “abolish all misers and hypocrites.”

A physician, S – , prints a statement that blood-letting exposes to an excess of light, another announces in two thick volumes, that diseases are elliptical.

Critics have said, referring to the works of Démons, that his Dialectic Quintessence and sextessence are a true quintessence of absurdity.339 Gleizes affirms that flesh is atheistical. Fuzi (a theologian) asserts that the menstrual blood has the property of quenching conflagrations.

Hannequin, who used to write in the air with his fingers, and had an aromal trumpet, by means of which he communicated with the spirits dispersed through the air, declares that in the future age many men shall become women and demigods.

Henrion, at the Académie des Inscriptions, advanced the theory that Adam was forty feet in height, Noah twenty-nine, Moses twenty-five, &c.

Leroux, the celebrated Paris Deputy, who believed in metempsychosis and the cabbala, defined love as “the ideality of the reality of a part of the totality of the Infinite Being,” &c., and wished to insert the principle of the triad in the preamble of his Constitution.

Asgill maintained that men might live for ever, if only they had faith.

It is true that, here and there, some new and vigorous notion emerges from the chaos of such minds, because the only symptom of genius developed in them by psychosis is a less degree of aversion to novelty, or, to employ my own terminology, of misoneism.340 Thus, for example, amid the most absurd opinions, Cianchettini has some very fine passages:

“All animals have the instinct of self-preservation, with the minimum of fatigue, of escaping from troublesome thoughts, and of enjoying the delights of life; and to obtain these things, liberty is indispensable to them.

“All animals, except man, gratify and always have gratified these instincts, and perhaps will always continue to do so. Mankind alone, constituted as a society, find themselves fettered, and in such a Way that no one has ever succeeded, not merely in bringing them into a state of peace and liberty, but even in showing how they may attain this end.

“Well – I propose to demonstrate this proposition. And, as a locked door cannot be opened without breaking it, save by means of a key or a pick-lock; so, as man has lost his liberty by means of the tongue, nothing but the tongue, or its equivalents, can set him free without injury to his nature.”

Amid the doggerel jargon of the Scottatinge, I find this beautiful line on Italy —

“Padrona e schiava sempre, ai figli tuoi nemica.”341We shall see, in Passanante’s biography, that sometimes, in his writings and still more in his speeches, he struck out vigorous and original ideas which, in fact, led many persons into error as to the nature and reality of his disease. I may mention the sentence, “Where the learned lose themselves, the ignorant man may triumph,” – and another, “History learnt from the people is more instructive than that which is studied in books.” Bluet distinguishes “the maid from the virgin, in that the first has the will for evil without the power, and the second has neither the power nor the will.”

It is natural that mattoids should repeat in their conceptions the ideas of stronger politicians and thinkers, but always in their own way, and always exaggerated. Thus Bosisio exaggerates the delicate consideration of our lovers of animals, and anticipates the ideas of Mlle. Clémence Royer and Comte on the necessity for the application of the Malthusian theory. In the same way, Detomasi, a dishonest broker, discovered a practical application (except for the morbid eroticism which he added to it) of the Darwinian system of natural selection. Cianchettini wishes to put Socialism into practice.

But the stamp of insanity is evident, not so much in the exaggeration of their ideas, as in the disproportion of the latter among themselves; so that, from some well-expressed and even sublime conception, we pass suddenly to one which is more than mediocre and paradoxical, nearly always opposed to the received ideas of the majority, and at variance with the position and education of the author. In short, we have that by means of which Don Quixote, instead of extorting our admiration, makes us smile. Yet his actions, in another age, and even in a different man, would have been admirable and heroic. In any case, among mattoids, traits of genius are rather the exception than the rule.342

Most of them show a deficiency rather than an exuberance of inspiration; they fill entire volumes, without sense or savour; they eke out the commonplaceness of their ideas and the poverty of their style with a multitude of points of interrogation and exclamation, with repeated signatures, with special words coined by themselves, as is the habit of monomaniacs; thus Menke already observed that some mattoids contemporary with himself had invented the words derapti felisan. Berbiguier created the word farfiderism. A monomaniac, Le Bardier, wrote a work entitled Dominatmosfheri intended to show farmers how to obtain double harvests, and sailors to avoid storms. He entitled himself Dominatmosfherifateur.343 Cianchettini invented the travaso of the idea; Pari invented cafungaia, and morbozoo, and we owe to Wahltuch, alitrologia and anthropomognotologia, and to G – lepidermocrinia and glossostomopatica.

We often find an eccentric handwriting, with vertical lines cut by horizontal ones and transverse furrows, even with unusually-formed letters, as in Cianchettini.

They frequently introduce drawings into their sentences, as if to heighten their force, thus returning (as we have already seen to be the case with megalomaniacs) to the ideographic writing of the ancients, in which the figure served as a determining symbol.

Wahltuch published two books on Psychography, a new kind of philosophic system which, however, has found a serious commentator in a sane philosopher – which speaks volumes for the seriousness of some philosophers. According to this system, ideas are represented by so many images impressed on each of the cerebral convolutions. Thus the symbol of Physics is a lighted candle; that of alitrology, or the faculty of judgment, is the nose (or the sense of smell); of ethics, a ring; and of motion, a fishing-hook. The author, despairing (and with good reason) of making himself understood in words, philosophises with his pencil, and has crammed his book with diagrams of brains covered with such figurative signs.

In order to prove the applicability of these principles to literature, he has presented us with a tragedy —Job– in which the characters have their heads covered with similar signs, and chant verses worthy of the system, e. g., “O that I could separate the two united conceptions of myself and impiety. I am just. Satan is impious.”344

The Jesuit missionary, Paoletti, wrote a book against St. Thomas, and illustrated it with a drawing of the vessels used in the Tabernacle, so as to determine the future condition of the sons of Adam with regard to predestination. The Divine and human wills are figured as two balls revolving in opposite directions, and finally meeting at a common centre.

The titles of all their works show an exuberance which is really singular. I possess one of eighteen lines, not counting a note included in the title-page itself, and intended to explain it. A socialistic work published in Australia, by an Italian, and in pure Italian, has a title arranged in the shape of a triumphal arch.

It is precisely in the title-page that nearly all of them at once betray the taint of madness. This example – from the work of the mattoid Démons – will suffice: “The demonstration of the fourth part of nothing is something; everything is the quintessence extracted from the quarter of nothing and that which depends on it, containing the precepts of the holy, magic, and devout invocations of Démons, to discover the origin of the evils which afflict France.”

Many have the crotchet of mixing up with their sentences accumulated series of numbers, which is also sometimes done by paralytics. In a mad production of Sovbira’s, entitled “666,” all the verses are accompanied by the number 666. The strange thing is that, at the same time, a certain Porter, in England, had published a work on the number 666, declaring it the most exquisite and perfect of numbers.345 Lazzaretti, too, had a singular partiality for this number. Spandri, Levron, and C – have a similar preference for the number 3. A special characteristic found in mattoids, and also, as we have already seen, in the insane, is that of repeating some words or phrases hundreds of times in the same page. Thus, in one of Passanante’s chapters, the word riprovate occurs about 143 times.

Some have had special paper manufactured for their works, like Wirgman, who had it made with different colours on the same sheet, at an enormous increase of expense, so that a volume of four hundred pages cost him over £2,200 sterling. Filon had every page of his book of a different colour.

Another characteristic is that of employing an orthography and caligraphy peculiar to themselves, with words in large type or underlined. They will sometimes write even private letters in double column, or with vertical lines traversed by horizontal and sometimes by diagonal ones. They sometimes underline one letter in preference to others in the same word (Passanante), or they write in detached verses like those of the Bible, or introduce points after every two or three words, as in the MS. (in my possession) of a certain Bellone, or parentheses, even one within the other, as Madrolle used to do, or notes upon notes, even in the title-page, as in the case of Cas – and of La – . The latter (a University professor) in a work of twelve pages has nine consisting of notes alone.

Hepain invented a physiological language, which consists in the main of our own letters reversed, and of numbers used in their places.

Many have a caligraphy quite peculiar to themselves, close, continuous, with lengthened letters, and always extremely legible.

Many (like some of the insane, whom they surpass in this point) continually intersperse their conversation with puns and plays on words. A certain Jassio wished to prove the analogy of the hand and the week in which God created the world, by means of a pun on the words main and semaine. Hécart, who had himself said that it is the peculiarity of the insane to occupy themselves with useless trifles, wrote the biography of the madmen of Valenciennes, and the strange book entitled Anagrammata, poëme en VII. chants, XCVe édition (as a matter of fact, it was the first), rev. corr. et augmentée; à Anagrammatopolis, l’an XIV. de l’ère anagrammatique (Valenciennes, 1821, 16º). The book is almost entirely composed of inversions of words. The following is an example:

“Lecteur; il sied que je vous diseQue le sbire fera la brise;Que le dupeur est sans pudeur,Qu’on peut maculer sans clameur…La nomade a mis la madonneA la paterne de PétronneQuand le grand Dacier était diacreLe caffier cultivé du fiacre.”And so on for twelve thousand lines, concluding with this:

“Moi je vais poser mon repos.”Here it is as well to note that, on the margin of a copy of the Anagrammata belonging to the Bibliothèque Nationale of Paris is the following confession, in the author’s handwriting, “Anagrams are one of the greatest inanities of which the human mind is capable; one must be a fool to amuse one’s self with them, and worse than a fool to make them.” This is a correct diagnosis of his case.

Filopanti, in the Dio Liberale, explains Luther’s propaganda by a caprice on the part of the Deity, who caused Mars to become a monk. The latter thus became Martin, and then Martin Luther.

The origin of Gleizes’ vegetarian mania was a dream, in which he heard a voice crying in his ears, “Gleizes means église.” He thus thought himself suddenly appointed by God to preach his doctrine to mankind. Du Monin has the plague decapitated, “Take away this head from hence; I fear that this head will deprive my people of their heads by a new mischief.”346

But a still more prevalent characteristic is the singular copiousness of their writings. Bluet left behind no less than 180 books, each more foolish than the other. We shall see how Mangione, who, in addition, was crippled in one hand and could not write, deprived himself of food to defray the cost of printing, and sometimes spent more than one hundred scudi per month to enable him to gratify his taste for authorship. We know how many reams of paper Passanante covered, and how he attached more importance to the publication of a foolish letter of his than to his own life. Guiteau used so much paper as to incur a considerable debt which he was unable to pay. The list of George Fox’s works is so long that the bibliographer Lowndes does not venture to give it. Howerlandt’s Essay on Tournay consists of 117 volumes.

Sometimes they content themselves with writing and printing their vagaries, and make no attempt to diffuse them among the public, though they assume that the latter must be acquainted with them.

In these writings, apart from their morbid prolixity, let it be noted that the aim is either futile, or absurd, or in complete contradiction with their social position and previous culture. Thus two physicians write on hypothetic geometry and astrology; a surgeon, a veterinary surgeon and an obstetric practitioner, on aerial navigation; a captain on rural economy; a sergeant on therapeutics; and a cook on high political questions. A theologian writes a treatise on menstrua, a carter on theology. Two porters are the authors of tragedies, and a custom-house officer of a work on sociology.

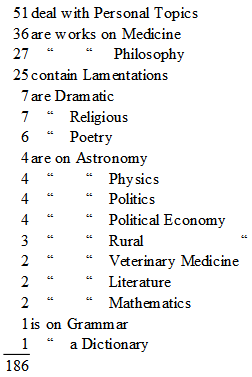

As to the subjects chosen, an examination of 186 insane books in my collection gives the following result:

I do not count miscellaneous works, such as controversial treatises, essays on mechanics, studies in magnetism, funeral orations, eccentric theological works, researches in literary history, proclamations, matrimonial advertisements, &c.

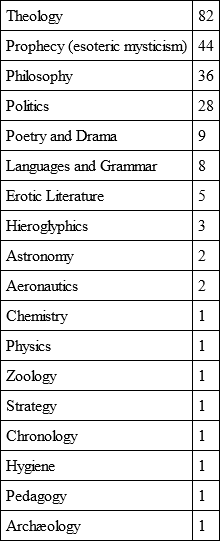

Some statistics compiled by Philomneste give a list of such books known in Europe, which are thus classified:

While poetry prevails among the insane, theology and prophecy predominate in the mattoids, and so on in diminishing proportions for the more abstract, uncertain and incomplete sciences, as we see by the scarcity of the naturalists and mathematicians. It is well to note the small number of atheists – three only, amid such a swarm of theologians and philosophers (162). Spiritualism, on the other hand, is so much in favour, that Philomneste gave up the task of cataloguing the works which treated of it.

All topics are welcome to mattoids, even those most foreign to their profession or occupation; but they are found to choose by preference the most grotesque and uncertain subjects, or questions which it is impossible to solve. Such are the quadrature of the circle, hieroglyphics, exposition of the Apocalypse, air-balloons, and spiritualism. They are also fond of treating the subjects most talked of – what one might call the questions of the day. Speaking of Démons, who has already been mentioned, Nodier said, “He was not a monomaniac – very much the contrary; he was a many-sided madman, always ready to repeat any strange thing that came to his ears, a chameleon-like dreamer, who insanely reflected the colours of the moment.”347 Thus, at the time of our great national deficits, projectors appeared by the dozen, with proposals to restore the Italian finances, either by means of assignats, or by the spoliation of the Jews or the clergy, by forced loans, &c. Later on, came the social and religious problem (Passanante, Lazzaretti, Bosisio, Cianchettini); at the present moment the question most under discussion is that of the pellagra.

Thus we have, among others, Pari, who has discovered the cause of the disease in certain fungi, which fall from the roofs of dirty huts into the peasants’ food, and make them ill. The proof is evident: photograph the section of a hut, and place it under the microscope, and you will find, on comparison, that fungi are more numerous than in town houses where pellagra is unknown.

But why do these fungi produce the pellagra? The reason is very simple. These fungi contain the substance fungina, which burns at 47° (sic). Now, when the outside temperature is at 13° and the body at 32° (sic) the two quantities of caloric are added together, and we burn! This is why sufferers from the pellagra appear scorched by the sun!

It is noteworthy that in nearly all – Bosisio, Cianchettini, Passanante, Mangione, De Tommasi, B – , – the convictions set forth in their written works are exceedingly deep and firmly fixed. They show as much absurdity and prolixity in their writings as they do common sense and prudence in their verbal answers – even rebutting objections with a single monosyllable, and explaining their own eccentricities with so much good sense and sometimes acuteness that the unlearned may well take their fancies for wisdom; while, later on, they relieve their insane impulses by covering reams of paper.