полная версия

полная версияThe Man of Genius

“The most remarkable thing, however, is the trophy resting on the head of the figure, which is the graphic expression, so to speak, of a song326 either written by him or adapted from other popular poetry. Each phrase of the song has its symbol in the trophy. Thus the word poison in the first verse is represented by the cup; the two daggers are likewise present; the end of life and the tomb are figured by a kind of sarcophagus or closed chest; love by two sprays of flowers. The bell of the second stanza is easily recognisable; the funereal music are the two trumpets crossed, lower down. The cross of the third stanza, and the priest (represented by a clerical hat) are not forgotten. It is curious that the gallows should be wanting to complete this trophy. The spoon and fork, by the by, are T – ’s favourite implements. They denote that he eats and drinks in slavery, or, as he says, in a convict-prison; and for this reason, he always wears a set, carved in wood by himself, in the button-hole of his coat, or in his cap.”

We may once more remind the reader that savages hand down their history by associating picture-signs with poetry.

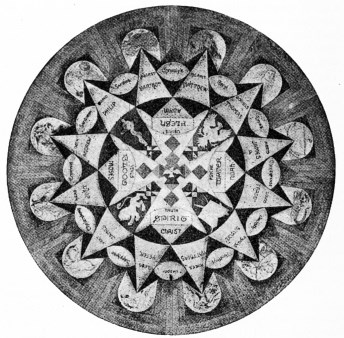

A most interesting example of elaborate symbolic faculty in a monomaniac, combined with higher artistic power than is usually found among the insane, has been recorded with very full illustrations by Dr. William Noyes.327 This patient studied art at Paris under Gérome and returned to America to become an illustrator of books and magazines. He developed systematic religious delusions, and frequently worked them out in very beautiful and artistic shapes, nine of which, all executed in the asylum at which he was confined, are here reproduced. The circular design is one of a series of twelve charts (one for each of the tribes of Israel) illustrating the progress of the Holy Spirit. They were all delicately coloured in water colours, the fine shading making it very difficult to give in black and white an adequate idea of the beauty of the original.

“In the centre is the dove representing the Holy Spirit, and surrounding it are seven different crosses [St. Andrew, St. Colomba, St. George, St. Michael, The Prophet, St. Evangeli, Royal Priesthood], and a close study will show the seven crosses, most ingeniously worked together. It is probable that in looking at the design closely for the first time one will suddenly see a new cross take shape before his eyes, and this indeed is what the patient says occurs with him. In describing the crosses he will say, for example, that in drawing the cross of St. Andrew the lines suddenly took a new shape and he found he had also made a cross of St. Michael. This to him is a matter of deep significance, and he feels that, his work is directly controlled by a higher power, and that the work of his fancy is really inspired.

“Outside these central crosses are the names of three ancient deities who were each characterized by some special attribute, and under these the parts of the body that the artist conceives these deities especially to have represented, and then comes the name of the Biblical personage in whom these elements were finally exemplified and embodied. To the left of the dove is Venus, representing Blood, exemplified in Moses; above is Osiris, representing Flesh, embodied in Adam; and to the right Psyche, representing Water, typified in Noah. These three are but the gross and material parts of Man, representing indeed necessary steps in his progress through life, but secondary and subordinate to the higher part of his nature represented by Truth and the Spirit – which receive their ultimate embodiment in Christ.

“The Lion denotes Might, and the Eagle signifies Emulation; but it is uncertain just what symbolism is connected with the serpent twining round the cross, and the open book crossed by a sword and pen, unless indeed this last may mean the Bible with the emblems of peace and war lying quietly within it, and it seems not unlikely that the serpent is emblematic of the Betrayal. For the rest of the design, however, we need make no inferences, as it corresponds closely with his description.

“Outside of the circle enclosing the crosses are the seals, sealing the Holy Spirit. In the large light triangles, or rather rays of the sun, are given the names of the twelve apostles, forming the Seal of the Prophet. Above these, in the same space, are the signs of the zodiac in the extreme points of the triangle, with the names of the parts of the body underneath, that these signs correspond to in the ancient mythology; this forms the Seal of the Zodiac. Between these large light coloured triangles are the twelve holy stones, represented as ovals, and with their names plainly distinguished in the cut, making the Seal of the Holy Stones. In the small triangles directly above the Holy Stones are given the names of the twelve tribes of Israel, but the colour of these in the chart (vermilion) is such that the lettering does not come out in the photographic negative. This gives the Seal of the Twelve Tribes. Directly beneath the Holy Stones, filling in the space between the bottom of each large triangle, is the Seal of the Germ, coloured dark green, and running down on each side of the top of these large triangles are small triangles, coloured dark red and forming the Seal of the Aceldama or Bloody Seal. On the circumference are the names of the constellations of the zodiac, and directly under these the names of the corresponding months of the year, and under these again are the mythological representations of the constellations, Leo (July) being at the top, and then in order to the right come Virgo (August), Libra (September), Scorpio (October), Sagittarius (November), Capricornus (December), Aquarius (January), Pisces (February), Aries (March), Taurus (April), Gemini (May), Cancer (June). This gives the last sealing of the Seed, the Seal of the Sun.

“It will be seen that beginning at the circumference at any point and going toward the centre there is a complete astronomical representation of the season of the year, first the name of the constellation, then in succession the month, the constellation depicted pictorially, the sign of the zodiac and the part of the human body corresponding in the old astronomy to this sign of the zodiac.”

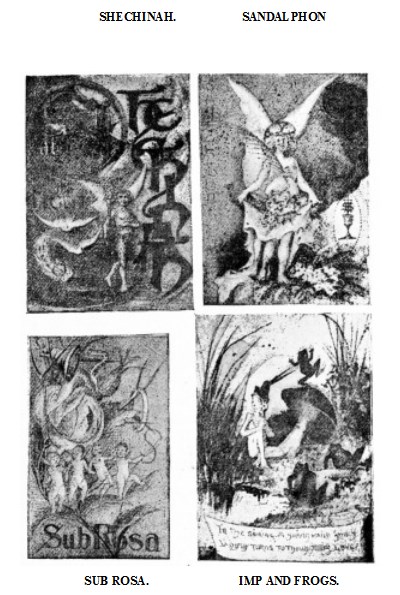

Of the four designs reproduced together, the first, the Shechinah, or Light of Love, represents that miraculous light or visible glory which was to the Jews a symbol of the Divine presence; the second represents the angel Sandalphon with the Holy Grail at the side and the letters Alpha and Omega at top (the design must be inverted to make out the Omega); the third, Sub Rosa, and the fourth, Imp and Frogs, are graceful fancies which sufficiently explain themselves, as does the Witch.

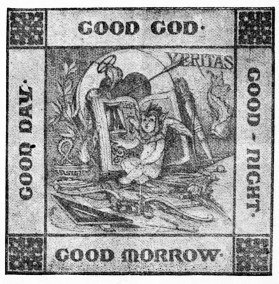

While working on these sketches, he made at the same time the design for a book-plate, representing Cupid learning the alphabet, and the entire design, he says, is full of symbolism – a favourite word with him. Cupid has his finger on Alpha, signifying the beginning of his education; above the book is Cupid’s target, with a heart for the centre, that he has pierced with an arrow, while the full quiver stands to the right. The curious fish under the Veritas represents the ΙΧΘΥΣ of the early Christians, while three crosses, symbolic of the Christian religion, are in the upper left-hand corner, brought out by heavy shading of the cross lines. On the book of knowledge is perched the dove, emblematic of purity, while the olive branch at the left of the book and the palm under the Fool’s Bauble give still other religious symbols. The lamp of knowledge is burning brightly in front of Cupid, while at his feet are the square, compass, triangle, and pencils, symbolizing the designer’s profession.

Minuteness of Detail.– In some insane artists, especially monomaniacs, we find an opposite characteristic – the exaggeration of particular details – the general effect being lost in obscurity through their excessive efforts after verisimilitude. Thus, in a landscape exhibited among those rejected from the Turin salon, not only was a general view of the country given, but every separate blade of grass could be distinguished. In another picture, intended to be very imposing, the strokes of the brush produced the effect of pencil shading.

Atavism.– Both minuteness and symbolism are themselves atavistic phenomena; but, in addition to them, there may be noted (in a large number of cases) a total absence of perspective, while the rest of the execution shows clearly enough that the author is not wanting in artistic sense. One would take him to be a true artist, but one brought up in China or ancient Egypt. Here we have evidently a kind of atavism explicable by arrested development of some one organ, and a corresponding backwardness in the products of that organ. A French captain, suffering from paralysis, drew figures stiff as Egyptian profiles. A megalomaniac of Reggio executed a coloured bas-relief, in which the disproportionate size of the feet and hands, the extreme smallness of the faces, and the stiffness of the limbs, completely recall the work of the thirteenth century. Another patient, at Genoa, carved bas-reliefs on pipes and on vases, exactly similar to those of the Neolithic Age.

THE WITCH.

ARABESQUES BY PARANOIAC ARTIST.

Raggi has sent me some flints carved by a monomaniac entirely ignorant of archæology, which, in the choice of figures and emblems, recall the style of Egyptian and Phœnician amulets. In these instances we see the influence of similar psychical conditions at work.

Arabesques.– In some few patients, M. Toselli has called my attention to a singular predilection for arabesques and ornaments which tend to assume a purely geometric form, without loss of elegance. This is the case with monomaniacs; in cases of dementia and acute mania there prevails a chaotic confusion, which, however, does not always imply absence of taste. I have seen an instance of this in a kind of ship, the work of a dementia patient, composed of an enormous number of little slips of wood, brilliantly coloured, very thin, and intertwined in an infinite variety of ways, the general effect being very graceful.

Obscenity.– In some work done by erotomaniacs, paralytics, and demented patients, the salient characteristic, both of the drawings and of the verses, is the most shameless indecency. Thus a cabinet-maker would carve virile members at every corner of a piece of furniture, or at the summits of trees. This, too, recalls many works of savages and of ancient races, in which the organs of sex are everywhere prominent. A captain at Genoa was fond of drawing scenes in a brothel. In many the obscene character is marked by the most singular pretexts, as though it were demanded by artistic requirements. A monomaniac priest used to sketch his figures nude, and then artfully drape them by means of lines which revealed the generative organs. He defended himself against criticism by saying that his figures could only appear indecent to those who were in search of evil.

M – illustrated his strange and often beautiful verses with innumerable daubs, representing animals of monstrous forms struggling with men and women, or monks and nuns, naked, in the most shameless attitudes.

In others the indecency is, if possible, still more evident, especially in cases of paralytic dementia. I remember an old man who used to draw a vulva on the address of his letters to his wife, surrounding it with obscene couplets in dialect.

It is a curious coincidence that two artists – one at Turin and the other at Reggio – who were both megalomaniacs, should both have had sodomitic instincts, which they combined with the delusion of being deities, and lords of the world, which they had created and emitted from their bodies. One of them (who, nevertheless, had a real artistic sense) painted a full-length picture of himself, naked, among women, ejecting worlds, and surrounded by all the symbols of power. This repeats, and at the same time explains, the Ithyphallic divinity of the Egyptians.

Criminality and Moral Insanity.– In this connection it is important to notice that the greater number of these artists show, in addition to their other forms of mania, a marked tendency to moral insanity, especially in the form of unnatural vice. The painter who produced the picture of “Delirium” was a pederast. The man who constructed the marvellous model of the Reggio Asylum, already alluded to, was neither draughtsman, sculptor, nor engineer. He was a madman, and, in addition, a thief, with unnatural tendencies. This man, whenever the fancy took him, escaped from the asylum, wandered about for some days, began to steal when he had exhausted the small amount of money he had about him, and when imprisoned declared himself a lunatic, and so got acquitted and sent back to Reggio, when, after a short interval, he would repeat the same line of conduct.

Dr. Tamburini told me that he, too, had been struck by the co-existence of artistic faculty and moral insanity in these patients.

Uselessness.– A characteristic common to many is the complete uselessness of the work to which they devote themselves; and here I recall once more Hécart’s dictum: —

“C’est le travail des fous d’épuiser leurs cervellesSur des riens fatigants, sur quelques bagatelles.”328A Genevan, affected by persecutory monomania, spent years in embroidering on egg-shells and lemons. Though her work was most beautiful, it could be of no advantage to her, for she kept it jealously concealed; and I myself, though she was very fond of me, never saw any of it till after her death.

Here we have, as in the case of artists of genius, the love of truth and beauty for their own sake alone, only that the aim is reversed.

Sometimes the work done, though very useful in itself, is of no advantage to the artist, and has no connection with his profession. Thus a captain, who had become insane, presented me with the model of a bed for violent patients, which, I believe, would be extremely useful in practice. Two other patients, together, made, out of a piece of beef-bone, some very neat match-boxes, ornamented with carvings in relief, which could be of no profit to themselves, since they refused to part with them for money.

There are, however, some exceptions. A melancholiac patient, with homicidal and suicidal tendencies, manufactured himself a very serviceable knife, fork, and spoon – metal ones not being allowed him – out of the bones which remained over from his dinner. A café-keeper at Colligno, a megalomaniac, compounded excellent liqueurs out of the scraps left over from meals, though of the most different kinds of food. A criminal lunatic constructed himself a key out of a number of small pieces of wood joined together. I do not count among these examples those who have prepared themselves real cuirasses of iron and stone – a piece of work in relation to the special delusion of persecutions, and implying an amount of labour out of proportion to the advantage obtained.

DELIRIUM.

Insanity as a subject.– Many choose insanity as the subject of their paintings. Professor Virgilio has furnished me with a very curious portrait of an insane patient at the moment of attack – the eyes rolling, the hair on end, the arms extended. Under his feet is the epigraph: “Delira” (“He is raving”). This is the work of an alcoholic pederast.

I think that a sane artist would have some difficulty in painting a closer likeness of delirium. This reminds me how frequently I have found, among the poets of asylums, the tendency to describe insanity; and it has been a favourite theme with great poets who have suffered from ill-health – Tasso, Lenau, Barbara, Musset. Mancini, immediately after his recovery, painted a woman offering for sale the picture executed by a madman; and Gill, in the hospital of Sainte-Anne, painted a raving maniac with terrible truth to nature.329

Absurdity.– One of the most salient characteristics of insane art is, as might be expected, absurdity, either in drawing or colouring. This is especially noteworthy in some maniacs, owing to the exaggerated association of ideas, through which the connecting links (which would serve to explain the author’s conception) are totally lost. Thus, an artist painted a “Marriage at Cana,” with all the figures of the apostles exceedingly well drawn; but in place of the figure of Christ was a large bunch of flowers.

Paralytic patients draw objects without any sense of proportion; their hens are the size of horses, and their cherries of melons; or, while striving after perfection in the design, the execution is merely childish. One, who believed himself a second Horace Vernet, drew horses by means of four straight strokes and a tail.330 Another drew all his figures upside down. Other dementia patients, owing to the same amnesia which is apparent in their speech, leave out the most essential points of their conception, like M – at Pesaro, who made an excellent drawing of a general, seated, but forgot the chair. (Frigerio.)

Imitation.– There are some who are very successful in imitation, but can produce nothing original; they will, for instance, copy the façade of the asylum, or heads of animals, with the minute accuracy of detail which characterizes primitive art. In this branch I have seen successful work done by cretins and idiots, the latter drawing in exactly the same manner as primitive man.

Uniformity.– Many continually repeat the same idea; thus one, mentioned by Frigerio, filled sheets of paper with a bee gnawing the head of an ant; another, who believed that he had been shot, would paint nothing but fire-arms; a third confined himself to arabesques.

Summary.– These traits explain the instances of partial perfection to be found in dementia patients; for a repetition of the same movement tends to bring it nearer and nearer to perfection. At other times, as we have seen in the extempore poets and authors of the asylum, it is the tenacity and energy of the hallucinations which makes a painter of a man who was never one before. Blake was able to picture to himself, as living and present, persons already dead, angels, &c. This was the case, also, with the strange insane poet, John Clare, who believed himself a spectator of the Battle of the Nile, and the death of Nelson; and was firmly convinced that he had been present at the death of Charles I. In fact, he described these events with such remarkable fidelity and accuracy, that it is scarcely probable he could have done it so well had he been in full possession of his reason – the more so, as he was entirely without culture.331 This explains why insane painters and poets are so numerous. It is easy to reproduce clearly what one sees clearly. Moreover, the imagination is most unrestrained when reason is least dominant; for the latter, by repressing hallucinations and illusions, deprives the average man of a true source of artistic and literary inspiration.

For the same reason, too, art itself, may, in its turn, encourage the development of mental disease. Vasari relates that one Spinelli, a painter of Arezzo, having attempted to paint the deformity of Lucifer, the latter appeared to him in a dream and reproached him with having made him so ugly. The painter was so affected by this apparition as to fall seriously ill; and it continued to haunt him for years.332

Music in the Insane.– Musical ability is often diminished in those who, previous to their illness, cultivated this art with passion. Dr. Adriani observed that musicians, under his care for insanity, almost entirely lost their powers. They could still play any piece, but it was done quite mechanically and without expression. Other dementia patients would play the same piece, sometimes even a few phrases, over and over again.

Donizetti, in the last stage of dementia, no longer recognized his favourite melodies. His last works show traces of that fatal influence which critics have also observed in Schumann’s symphony of the “Bride of Messina,” composed during his attacks of insanity.333

These facts, however, do not contradict our assertion that insanity awakens new artistic qualities in persons not previously gifted in that way; they only show that (as we have seen in the case of professional painters) it can give no additional power or skill to those who already possessed them when attacked by disease.

A megalomaniac – formerly a syphilitic patient – under the care of Dr. Tamburini, sang beautiful airs when under excitement, at the same time, instead of playing an accompaniment, she improvised, on the pianoforte, two distinct motives which had no connection with each other or the air she was singing. This fact confirms the observations of Luys as to the independent action of the cerebral hemispheres.

A young man attacked by pellagra, who recovered in my hospital, composed expressive and original melodies.

M. Raggi told me that he had had under his care a melancholic patient who, during her attacks, played without enthusiasm, and even with repugnance, but, when the fit passed off, would spend whole days at the piano, and execute the most difficult partitions with a truly artistic enthusiasm. In the same way, a paralytic showed, through the whole course of his illness, a genuine musical mania, during which he imitated all instruments, and agitated himself, in frantic enthusiasm, at the piano passages.

Raggi also observed a paralytic dementia patient who, after breaking his thigh-bone by a leap from a window, rendered every bandage which could be devised useless by singing, for days together, motives from Il Trovatore at the top of his voice, and accompanying his singing with abrupt rhythmical movements of the pelvis. A fancy for monotonous chanting also showed itself in another paralytic, who believed himself to be a great admiral.

In maniacs, acute and joyous notes predominate, and, still more, the repetition of the rhythm.

Every one who has paid even a short visit to an asylum has noticed the frequency of singing and shouting and “high and thin voices, and with them a sound of hands.”334 Nor is it hard to understand this, if we remember how Spencer and Ardigò have shown that the law of rhythm is the most general form under which, in the whole of nature, energy is manifested, from the crystal to the star, or to the animal organism. Man, therefore, only follows a general organic law in giving way to this impulse, which he does the more readily the less he is controlled by reason. This explains the number of poets of the new school who are found in asylums. This is the reason why savage nations have a natural inclination for music; and a missionary told Spencer that many to whom he taught the Psalms, with music, in the evening, could repeat them by heart on the following day.

Savages, in speaking, make use of a sort of monotonous chant analogous to our recitative. Primitive poetry was always sung, whence all the different words connected with singing applied to poetry and poets. The mysterious magic formulas and recipes of the ancients335 were also sung, or chanted, whence the word “enchantment.” Even at the present day, in the neighbourhood of Novi and Oulx, I have heard peasant-women, in making inquiries of one another, modulate their voices in true musical rhythm. Modern Improvvisatori do not seem able to produce their verses except when singing, and agitating all their muscles.

It must be remembered that, according to the observations of Herbert Spencer,336 “the act of singing employs and exaggerates the signs of the natural language of passion. Mental excitement is transformed into muscular energy. An infant will laugh and bound in its nurse’s arms at the sight of a brilliant colour, or the hearing of a new sound.” Strong sensations or painful emotions cause us to gesticulate; in short, they excite the muscular system, which is acted upon in proportion to the intensity of the sensations. Slight pain calls forth a groan, greater pain a cry: the pitch of the voice varies with the force of the emotion, so that, in the strongest emotions, it rises to the octave, or higher; and singing is always involuntarily accompanied by tremors and agitations of the muscles.