Полная версия

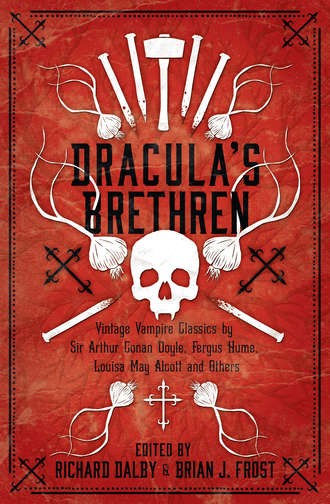

Dracula’s Brethren

‘Good!’ the philosopher Homa thought to himself, and he began repeating the exorcisms almost aloud. At last, quick as lightning, he sprang from under the old woman and in his turn leapt on her back. The old woman, with a tiny tripping step, ran so fast that her rider could scarcely breathe. The earth flashed by under him; everything was clear in the moonlight, though the moon was not full; the ground was smooth, but everything flashed by so rapidly that it was confused and indistinct. He snatched up a piece of wood that lay on the road and began whacking the old woman with all his might. She uttered wild howls; at first they were angry and menacing, then they grew fainter, sweeter, clearer, then rang out gently like delicate silver bells that stabbed him to the heart; and the thought flashed through his mind: was it really an old woman?

‘Oh, I can do no more!’ she murmured, and sank exhausted on the ground.

He stood up and looked into her face (there was the glow of sunrise, and the golden domes of the Kiev churches were gleaming in the distance): before him lay a lovely creature with luxuriant tresses all in disorder and eyelashes as long as arrows. Senseless she tossed her bare white arms and moaned, looking upwards with eyes full of tears.

Homa trembled like a leaf on a tree; he was overcome by pity and a strange emotion and timidity, feelings he could not himself explain. He set off running, full speed. His heart throbbed uneasily as he went, and he could not account for the strange new feeling that had taken possession of it. He did not want to go back to the farm; he hastened to Kiev, pondering all the way on this incomprehensible adventure.

There was scarcely a student left in the town. All had dispersed about the countryside, either to situations, or simply without them; because in the villages of Little Russia they could get dumplings, cheese, sour cream, and puddings as big as a hat without paying a kopeck for them. The big rambling house in which the students were lodged was absolutely empty, and although the philosopher rummaged in every corner, and even felt in all the holes and cracks in the roof, he could not find a bit of bacon or even a stale roll such as were commonly hidden there by the students.

The philosopher, however, soon found means to improve his lot: he walked whistling three times through the market, finally winked at a young widow in a yellow bonnet who was selling ribbons, shot and wheels – and was that very day regaled with wheat dumplings, a chicken … in short, there is no telling what was on the table laid for him in a little mud house in the middle of a cherry orchard.

That same evening the philosopher was seen in a tavern: he was lying on the bench, smoking a pipe as his habit was, and in the sight of all he flung the Jew who kept the house a gold coin. A mug stood before him. He looked at all that came in and went out with eyes full of cool satisfaction, and thought no more of his extraordinary adventure.

Meanwhile rumours were circulating everywhere that the daughter of one of the richest Cossack sotniks,fn1 who lived nearly forty miles from Kiev, had returned one day from a walk, terribly injured, hardly able to crawl home to her father’s house, was lying at the point of death, and had expressed a wish that one of the Kiev seminarists, Homa Brut, should read the prayers over her and the psalms for three days after her death. The philosopher heard of this from the rector himself, who summoned him to his room and informed him that he was to set off on the journey without any delay, that the noble sotnik had sent servants and a carriage to fetch him.

The philosopher shuddered from an unaccountable feeling which he could not have explained to himself. A dark presentiment told him that something evil was awaiting him. Without knowing why, he bluntly declared that he would not go.

‘Listen, Domine Homa!’ said the rector. (On some occasions he expressed himself very courteously with those under his authority.) ‘Who the devil is asking you whether you want to go or not? All I have to tell you is that if you go on jibbing and making difficulties, I’ll order you such a whacking with a young birch tree, on your back and the rest of you, that there will be no need for you to go to the bath after.’

The philosopher, scratching behind his ear, went out without uttering a word, proposing at the first suitable opportunity to put his trust in his heels. Plunged in thought he went down the steep staircase that led into a yard shut in by poplars, and stood still for a minute, hearing quite distinctly the voice of the rector giving orders to his butler and some one else – probably one of the servants sent to fetch him by the sotnik.

‘Thank his honour for the grain and the eggs,’ the rector was saying: ‘and tell him that as soon as the books about which he writes are ready I will send them at once, I have already given them to a scribe to be copied, and don’t forget, my good man, to mention to his honour that I know there are excellent fish at his place, especially sturgeon, and he might on occasion send some; here in the market it’s bad and dear. And you, Yavtuh, give, the young fellows a cup of vodka each, and bind the philosopher or he’ll be off directly.’

‘There, the devil’s son!’ the philosopher thought to himself. ‘He scented it out, the wily long-legs!’ He went down and saw a covered chaise, which he almost took at first for a baker’s oven on wheels. It was, indeed, as deep as the oven in which bricks are baked. It was only the ordinary Cracow carriage in which Jews travel fifty together with their wares to all the towns where they smell out a fair. Six healthy and stalwart Cossacks, no longer young, were waiting for him. Their tunics of fine cloth, with tassels, showed that they belonged to a rather important and wealthy master; some small scars proved that they had at some time been in battle, not ingloriously.

‘What’s to be done? What is to be must be!’ the philosopher thought to himself and, turning to the Cossacks, he said aloud: ‘Good day to you, comrades!’

‘Good health to you, master philosopher,’ some of the Cossacks replied.

‘So I am to get in with you? It’s a goodly chaise!’ he went on, as he clambered in, ‘we need only hire some musicians and we might dance here.’

‘Yes, it’s a carriage of ample proportions,’ said one of the Cossacks, seating himself on the box beside the coachman, who had tied a rag over his head to replace the cap which he had managed to leave behind at a pot-house. The other five and the philosopher crawled into the recesses of the chaise and settled themselves on sacks filled with various purchases they had made in the town. ‘It would be interesting to know,’ said the philosopher, ‘if this chaise were loaded up with goods of some sort, salt for instance, or iron wedges, how many horses would be needed then?’

‘Yes,’ the Cossack, sitting on the box, said after a pause, ‘it would need a sufficient number of horses.’

After this satisfactory reply the Cossack thought himself entitled to hold his tongue for the remainder of the journey.

The philosopher was extremely desirous of learning more in detail, who this sotnik was, what he was like, what had been heard about his daughter who in such a strange way returned home and was found on the point of death, and whose story was now connected with his own, what was being done in the house, and how things were there. He addressed the Cossacks with inquiries, but no doubt they too were philosophers, for by way of a reply they remained silent, smoking their pipes and lying on their backs. Only one of them turned to the driver on the box with a brief order. ‘Mind, Overko, you old booby, when you are near the tavern on the Tchuhraylovo road, don’t forget to stop and wake me and the other chaps, if any should chance to drop asleep.’

After this he fell asleep rather audibly. These instructions were, however, quite unnecessary for, as soon as the gigantic chaise drew near the pot-house, all the Cossacks with one voice shouted: ‘Stop!’ Moreover, Overko’s horses were already trained to stop of themselves at every pot-house.

In spite of the hot July day, they all got out of the chaise and went into the low-pitched dirty room, where the Jew who kept the house hastened to receive his old friends with every sign of delight. The Jew brought from under the skirt of his coat some ham sausages, and, putting them on the table, turned his back at once on this food forbidden by the Talmud. All the Cossacks sat down round the table; earthenware mugs were set for each of the guests. Homa had to take part in the general festivity, and, as Little Russians infallibly begin kissing each other or weeping when they are drunk, soon the whole room resounded with smacks. ‘I say, Spirid, a kiss.’ ‘Come here, Dorosh, I want to embrace you!’

One Cossack with grey moustaches, a little older than the rest, propped his cheek on his hand and began sobbing bitterly at the thought that he had no father nor mother and was all alone in the world. Another one, much given to moralising, persisted in consoling him, saying: ‘Don’t cry; upon my soul, don’t cry! What is there in it …? The Lord knows best, you know.’

The one whose name was Dorosh became extremely inquisitive, and, turning to the philosopher Homa, kept asking him: ‘I should like to know what they teach you in the college. Is it the same as what the deacon reads in church, or something different?’

‘Don’t ask!’ the sermonising Cossack said emphatically: ‘let it be as it is, God knows what is wanted, God knows everything.’

‘No, I want to know,’ said Dorosh, ‘what is written there in those books? Maybe it is quite different from what the deacon reads.’

‘Oh, my goodness, my goodness!’ said the sermonising worthy, ‘and why say such a thing; it’s as the Lord wills. There is no changing what the Lord has willed!’

‘I want to know all that’s written. I’ll go to college, upon my word, I will. Do you suppose I can’t learn? I’ll learn it all, all!’

‘Oh my goodness …!’ said the sermonising Cossack, and he dropped his head on the table, because he was utterly incapable of supporting it any longer on his shoulders. The other Cossacks were discussing their masters and the question why the moon shone in the sky. The philosopher, seeing the state of their minds, resolved to seize his opportunity and make his escape. To begin with he turned to the grey-headed Cossack who was grieving for his father and mother.

‘Why are you blubbering, uncle?’ he said, ‘I am an orphan myself! Let me go in freedom, lads! What do you want with me?’

‘Let him go!’ several responded, ‘why, he is an orphan, let him go where he likes.’

‘Oh, my goodness, my goodness!’ the moralising Cossack articulated, lifting his head. ‘Let him go!’

‘Let him go where he likes!’

And the Cossacks meant to lead him out into the open air themselves, but the one who had displayed his curiosity stopped them, saying: ‘Don’t touch him. I want to talk to him about college: I am going to college myself …’

It is doubtful, however, whether the escape could have taken place, for when the philosopher tried to get up from the table his legs seemed to have become wooden, and he began to perceive such a number of doors in the room that he could hardly discover the real one.

It was evening before the Cossacks bethought themselves that they had further to go. Clambering into the chaise, they trailed along the road, urging on the horses and singing a song of which nobody could have made out the words or the sense. After trundling on for the greater part of the night, continually straying off the road, though they knew every inch of the way, they drove at last down a steep hill into a valley, and the philosopher noticed a paling or hurdle that ran alongside, low trees and roofs peeping out behind it. This was a big village belonging to the sotnik. By now it was long past midnight; the sky was dark, but there were little stars twinkling here and there. No light was to be seen in a single cottage. To the accompaniment of the barking of dogs, they drove into the courtyard. Thatched barns and little houses came into sight on both sides; one of the latter, which stood exactly in the middle opposite the gates, was larger than the others, and was apparently the sotnik’s residence. The chaise drew up before a little shed that did duty for a barn, and our travellers went off to bed. The philosopher, however, wanted to inspect the outside of the sotnik’s house; but, though he stared his hardest, nothing could be seen distinctly; the house looked to him like a bear; the chimney turned into the rector. The philosopher gave it up and went to sleep.

When he woke up, the whole house was in commotion: the sotnik’s daughter had died in the night. Servants were running hurriedly to and fro; some old women were crying; an inquisitive crowd was looking through the fence at the house, as though something might be seen there. The philosopher began examining at his leisure the objects he could not make out in the night. The sotnik’s house was a little, low-pitched building, such as was usual in Little Russia in old days; its roof was of thatch; a small, high, pointed gable with a little window that looked like an eye turned upwards, was painted in blue and yellow flowers and red crescents; it was supported on oak posts, rounded above and hexagonal below, with carving at the top. Under the gable was a little porch with seats on each side. There were verandahs round the house resting on similar posts, some of them carved in spirals. A tall pyramidal pear tree, with trembling leaves, made a patch of green in front of the house. Two rows of barns for storing grain stood in the middle of the yard, forming a sort of wide street leading to the house. Beyond the barns, close to the gate, stood facing each other two three-cornered storehouses, also thatched. Each triangular wall was painted in various designs and had a little door in it. On one of them was depicted a Cossack sitting on a barrel, holding a mug above his head with the inscription: ‘I’ll drink it all!’ On the other, there was a bottle, flagons, and at the sides, by way of ornament, a horse upside down, a pipe, a tambourine, and the inscription: ‘Wine is the Cossack’s comfort!’ A drum and brass trumpets could be seen through the huge window in the loft of one of the barns. At the gates stood two cannons. Everything showed that the master of the house was fond of merrymaking, and that the yard often resounded with the shouts of revellers. There were two windmills outside the gate. Behind the house stretched gardens, and through the treetops the dark caps of chimneys were all that could be seen of cottages smothered in green bushes. The whole village lay on the broad sloping side of a hill. The steep side, at the very foot of which lay the courtyard, made a screen from the north. Looked at from below, it seemed even steeper, and here and there on its tall top uneven stalks of rough grass stood up black against the clear sky; its bare aspect was somehow depressing; its clay soil was hollowed out by the fall and trickle of rain. Two cottages stood at some distance from each other on its steep slope; one of them was overshadowed by the branches of a spreading apple tree, banked up with soil and supported by short stakes near the root. The apples, knocked down by the wind, were falling right into the master’s courtyard. The road, coiling about the hill from the very top, ran down beside the courtyard to the village. When the philosopher scanned its terrific steepness and recalled their journey down it the previous night, he came to the conclusion that either the sotnik had very clever horses or that the Cossacks had very strong heads to have managed, even when drunk, to escape flying head over heels with the immense chaise and baggage. The philosopher was standing on the very highest point in the yard. When he turned and looked in the opposite direction he saw quite a different view. The village sloped away into a plain. Meadows stretched as far as the eye could see; their brilliant verdure was deeper in the distance, and whole rows of villages looked like dark patches in it, though they must have been more than fifteen miles away. On the right of the meadowlands was a line of hills, and a hardly perceptible streak of flashing light and darkness showed where the Dnieper ran.

‘Ah, a splendid spot!’ said the philosopher, ‘this would be the place to live, fishing in the Dnieper and the ponds, bird-catching with nets, or shooting king-snipe and little bustard. Though I do believe there would be a few great bustards too in those meadows! One could dry lots of fruit, too, and sell it in the town, or, better still, make vodka of it, for there’s no drink to compare with fruit-vodka. But it would be just as well to consider how to slip away from here.’

He noticed outside the fence a little path completely overgrown with weeds; he was mechanically setting his foot on it with the idea of simply going first out for a walk, and then stealthily passing between the cottages and dashing out into the open country, when he suddenly felt a rather strong hand on his shoulder.

Behind him stood the old Cossack who had on the previous evening so bitterly bewailed the death of his father and mother and his own solitary state.

‘It’s no good your thinking of making off, Mr Philosopher!’ he said: ‘this isn’t the sort of establishment you can run away from; and the roads are bad, too, for anyone on foot; you had better come to the master: he’s been expecting you this long time in the parlour.’

‘Let us go! To be sure … I’m delighted,’ said the philosopher, and he followed the Cossack.

The sotnik, an elderly man with grey moustaches and an expression of gloomy sadness, was sitting at a table in the parlour, his head propped on his hands. He was about fifty; but the deep despondency on his face and its wan pallor showed that his soul had been crushed and shattered at one blow, and all his old gaiety and noisy merrymaking had gone for ever. When Homa went in with the old Cossack, he removed one hand from his face and gave a slight nod in response to their low bows.

Homa and the Cossack stood respectfully at the door.

‘Who are you, where do you come from, and what is your calling, good man?’ said the sotnik, in a voice neither friendly nor ill-humoured.

‘A bursar, student in philosophy, Homa Brut …’

‘Who was your father?’

‘I don’t know, honoured sir.’

‘Your mother?’

‘I don’t know my mother either. It is reasonable to suppose, of course, that I had a mother; but who she was and where she came from, and when she lived – upon my soul, good sir, I don’t know.’

The old man paused and seemed to sink into a reverie for a minute.

‘How did you come to know my daughter?’

‘I didn’t know her, honoured sir, upon my word, I didn’t. I have never had anything to do with young ladies, never in my life. Bless them, saving your presence!’

‘Why did she fix on you and no other to read the psalms over her?’

The philosopher shrugged his shoulders. ‘God knows how to make that out. It’s a well-known thing, the gentry are for ever taking fancies that the most learned man couldn’t explain, and the proverb says: “The devil himself must dance at the master’s bidding.”’

‘Are you telling the truth, philosopher?’

‘May I be struck down by thunder on the spot if I’m not.’

‘If she had but lived one brief moment longer,’ the sotnik said to himself mournfully, ‘I should have learned all about it. “Let no one else read over me, but send, father, at once to the Kiev Seminary and fetch the bursar, Homa Brut; let him pray three nights for my sinful soul. He knows …!” But what he knows, I did not hear: she, poor darling, could say no more before she died. You, good man, are no doubt well known for your holy life and pious works, and she, maybe, heard tell of you.’

‘Who? I?’ said the philosopher, stepping back in amazement. ‘I – holy life!’ he articulated, looking straight in the sotnik’s face. ‘God be with you, sir! What are you talking about! Why – though it’s not a seemly thing to speak of – I paid the baker’s wife a visit on Maundy Thursday.’

‘Well … I suppose there must be some reason for fixing on you. You must begin your duties this very day.’

‘As to that, I would tell your honour … Of course, any man versed in holy scripture may, as far as in him lies … but a deacon or a sacristan would be better fitted for it. They are men of understanding, and know how it is all done; while I … Besides I haven’t the right voice for it, and I myself am good for nothing. I’m not the figure for it.’

‘Well, say what you like, I shall carry out all my darling’s wishes, I will spare nothing. And if for three nights from today you duly recite the prayers over her, I will reward you, if not … I don’t advise the devil himself to anger me.’

The last words were uttered by the sotnik so vigorously that the philosopher fully grasped their significance.

‘Follow me!’ said the sotnik.

They went out into the hall. The sotnik opened the door into another room, opposite the first. The philosopher paused a minute in the hall to blow his nose and crossed the threshold with unaccountable apprehension.

The whole floor was covered with red cotton stuff. On a high table in the corner under the holy images lay the body of the dead girl on a coverlet of dark blue velvet adorned with gold fringe and tassels. Tall wax candles, entwined with sprigs of guelder rose, stood at her feet and head, shedding a dim light that was lost in the brightness of daylight. The dead girl’s face was hidden from him by the inconsolable father, who sat down facing her with his back to the door. The philosopher was impressed by the words he heard:

‘I am grieving, my dearly beloved daughter, not that in the flower of your age you have left the earth, to my sorrow and mourning, without living your allotted span; I grieve, my darling, that I know not him, my bitter foe, who was the cause of your death. And if I knew the man who could but dream of hurting you, or even saying anything unkind of you, I swear to God he should not see his children again, if he be old as I, nor his father and mother, if he be of that time of life, and his body should be cast out to be devoured by the birds and beasts of the steppe! But my grief it is, my wild marigold, my birdie, light of my eyes, that I must live out my days without comfort, wiping with the skirt of my coat the trickling tears that flow from my old eyes, while my enemy will be making merry and secretly mocking at the feeble old man …’

He came to a standstill, due to an outburst of sorrow, which found vent in a flood of tears.

The philosopher was touched by such inconsolable sadness; he coughed, uttering a hollow sound in the effort to clear his throat. The sotnik turned round and pointed him to a place at the dead girl’s head, before a small lectern with books on it.

‘I shall get through three nights somehow,’ thought the philosopher: ‘and the old man will stuff both my pockets with gold pieces for it.’

He drew near, and clearing his throat once more, began reading, paying no attention to anything else and not venturing to glance at the face of the dead girl. A profound stillness reigned in the apartment. He noticed that the sotnik had withdrawn. Slowly, he turned his head to look at the dead, and …

A shudder ran through his veins: before him lay a beauty whose like had surely never been on earth before. Never, it seemed, could features have been formed in such striking yet harmonious beauty. She lay as though living: the lovely forehead, fair as snow, as silver, looked deep in thought; the even brows – dark as night in the midst of sunshine – rose proudly above the closed eyes; the eyelashes, that fell like arrows on the cheeks, glowed with the warmth of secret desires; the lips were rubies, ready to break into the laugh of bliss, the flood of joy … But in them, in those very features, he saw something terrible and poignant. He felt a sickening ache stirring in his heart, as though, in the midst of a whirl of gaiety and dancing crowds, someone had begun singing a funeral dirge. The rubies of her lips looked like blood surging up from her heart. All at once he was aware of something dreadfully familiar in her face. ‘The witch!’ he cried in a voice not his own, as, turning pale, he looked away and fell to repeating his prayers. It was the witch that he had killed!