полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4)

Stating the general purposes of the United States, Marshall strikes at the efforts of France to compel America to do what France wishes and in the manner that France wishes, instead of doing what American interests require and in the manner America thinks wisest.

The American people, he asserts, "must judge exclusively for themselves how far they will or ought to go in their efforts to acquire new rights or establish new principles. When they surrender this privilege, they cease to be independent, and they will no longer deserve to be free. They will have surrendered into other hands the most sacred of deposits – the right of self-government; and instead of approbation, they will merit the contempt of the world."688

Marshall states the economic and business reasons why the United States, of all countries, must depend upon commerce and the consequent necessity for the Jay Treaty. He tartly informs Talleyrand that in doing so the American Government was "transacting a business exclusively its own." Marshall denies the insinuation that the negotiations of the Jay Treaty had been unusually secret, but sarcastically observes that "it is not usual for nations about to enter into negotiations to proclaim to others the various objects to which those negotiations may possibly be directed. Such is not, nor has it ever been, the principle of France." To suppose that America owed such a duty to France, "is to imply a dependence to which no Government ought willingly to submit."689

Marshall then sets forth specifically the American complaints against the French Government,690 and puts in parallel columns the words of the Jay Treaty to which the French objected, and the rules which the French Directory pretended were justified by that treaty. So strong is Marshall's summing up of the case in these portions of the American memorial that it is hard for the present-day reader to see how even the French Directory of that lawless time could have dared to attempt to withstand it, much less to refuse further negotiations.

Drawing to a conclusion, Marshall permits a lofty sarcasm to lighten his weighty argument. "America has accustomed herself," he observes, "to perceive in France only the ally and the friend. Consulting the feelings of her own bosom, she [America] has believed that between republics an elevated and refined friendship could exist, and that free nations were capable of maintaining for each other a real and permanent affection. If this pleasing theory, erected with so much care, and viewed with so much delight, has been impaired by experience, yet the hope continues to be cherished that this circumstance does not necessarily involve the opposite extreme."691

Then, for a moment, Marshall indulges his eloquence: "So intertwined with every ligament of her heart have been the cords of affection which bound her to France, that only repeated and continued acts of hostility can tear them asunder."692

Finally he tells Talleyrand that the American envoys, "searching only for the means of effecting the objects of their mission, have permitted no personal considerations to influence their conduct, but have waited, under circumstances beyond measure embarrassing and unpleasant, with that respect which the American Government has so uniformly paid to that of France, for permission to lay before you, citizen Minister, these important communications with which they have been charged." But, "if no such hope" remains, "they [the envoys] have only to pray that their return to their own country may be facilitated."693

But Marshall's extraordinary power of statement and logic availed nothing with Talleyrand and the Directory. "I consider Marshall, whom I have heard speak on a great subject,694 as one of the most powerful reasoners I ever met with either in public or in print," writes William Vans Murray from The Hague, commenting on the task of the envoys. "Reasoning in such cases will have a fine effect in America, but to depend upon it in Europe is really to place Quixote with Ginés de Passamonte and among the men of the world whom he reasoned with, and so sublimely, on their way to the galleys. They answer him, with you know stones and blows, though the Knight is an armed as well as an eloquent Knight."695

The events which had made Marshall and Pinckney more resolute in demanding respectful treatment had made Gerry more pliant to French influence. "Mr. Gerry is to see Mr. Talleyrand the day after to-morrow. Three appointments have been made by that gentleman," Marshall notes in his Journal, "each of which Mr. Gerry has attended and each of which Mr. Talleyrand has failed to attend; nor has any apology for these disappointments been thought necessary."696 Once more Gerry waits on Talleyrand, who remains invisible.697 And now again Beaumarchais appears. The Directory issues more and harsher decrees against American commerce. Marshall's patience becomes finite. "I prepared to-day a letter to the Minister remonstrating against the decree, … subjecting to confiscation all neutral vessels having on board any article coming out of England or its possessions." The letter closes by "requesting our passports."698

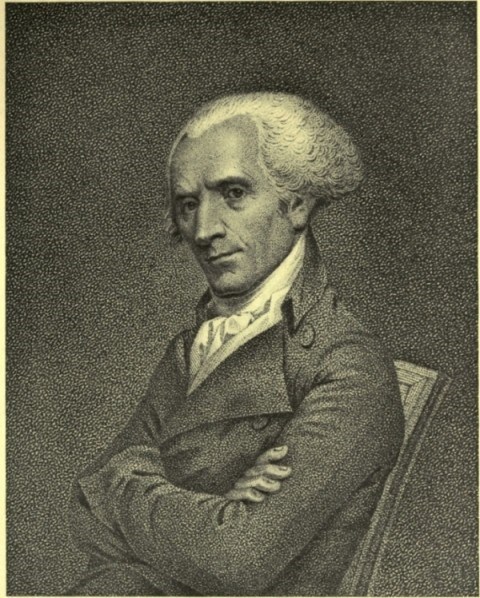

ELBRIDGE GERRY

Marshall's memorial of the American case remained unread. One of Talleyrand's many secretaries asked Gerry "what it contained? (for they could not take the trouble to read it) and he added that such long letters were not to the taste of the French Government who liked a short address coming straight to the point."699 Gerry, who at last saw Talleyrand, "informed me [Marshall] that communications & propositions had been made to him by that Gentleman, which he [Gerry] was not at liberty to impart to Genl Pinckney or myself." Upon the outcome of his secret conferences with Talleyrand, said Gerry, "probably depended peace or war."700

Gerry's "communication necessarily gives birth to some very serious reflections," Marshall confides to his Journal. He recalls the attempts to frighten the envoys "from our first arrival" – the threats of "a variety of ills … among others with being ordered immediately to quit France," none of them carried out; "the most haughty & hostile conduct … towards us & our country and yet … an unwillingness … to profess the war which is in fact made upon us."701

A French agent, sent by the French Consul-General in America, just arrived in Paris, "has probably brought with him," Marshall concludes, "accurate details of the state of parties in America… I should think that if the French Government continues its hostility and does not relax some little in its hauteur its party in the United States will no longer support it. I suspect that some intelligence of this complexion has been received … whether she [France] will be content to leave us our Independence if she can neither cajole or frighten us out of it or will even endeavor to tear it from us by open war there can be no doubt of her policy in one respect – she will still keep up and cherish, if it be possible, … her party in the United States." Whatever course France takes, Marshall thinks will be "with a view to this her primary object."

Therefore, reasons Marshall, Talleyrand will maneuver to throw the blame on Pinckney and himself if the mission fails, and to give Gerry the credit if it succeeds. "I am led irresistibly by this train of thought to the opinion that the communication made to Mr. Gerry in secret is a proposition to furnish passports to General Pinckney and myself and to retain him for the purpose of negotiating the differences between the two Republics." This would give the advantage to the French party in any event.

"I am firmly persuaded of his [Talleyrand's] unwillingness to dismiss us while the war with England continues in its present uncertain state. He believed that Genl Pinckney and myself are both determined to remain no longer unless we can be accredited." Gerry had told Marshall that he felt the same way; "but," says Marshall, "I am persuaded the Minister [Talleyrand] does not think so. He would on this account as well as on another which has been the base of all propositions for an accommodation [the loan and the bribe] be well pleased to retain only one minister and to chuse that one [Gerry]."702

Marshall and Pinckney decided to let Gerry go his own gait. "We shall both be happy if, by remaining without us, Mr. Gerry can negotiate a treaty which shall preserve the peace without sacrificing the independence of our country. We will most readily offer up all personal considerations as a sacrifice to appease the haughtiness of this Republic."703

Marshall gave Gerry the letter on the decree and passport question "and pressed his immediate attention to it." But Gerry was too excited by his secret conferences with Talleyrand to heed it. Time and again Gerry, bursting with importance, was closeted with the Foreign Minister, hinting to his colleagues that he held peace or war in his hand. Marshall bluntly told him that Talleyrand's plan now was "only to prevent our taking decisive measures until the affairs of Europe shall enable France to take them. I have pressed him [Gerry] on the subject of the letter concerning the Decree but he has not yet read it."704

Talleyrand and Gerry's "private intercourse still continues," writes Marshall on February 10. "Last night after our return from the Theatre Mr. Gerry told me, just as we were separating to retire each to his own apartment, that he had had in the course of the day a very extraordinary conversation with" a clerk of Talleyrand. It was, of course, secret. Marshall did not want to hear it. Gerry said he could tell his colleagues that it was on the subject of money. Then, at last, Marshall's restraint gave way momentarily and his anger, for an instant, blazed. Money proposals were useless; Talleyrand was playing with the Americans, he declared. "Mr. Gerry was a little warm and the conversation was rather unpleasant. A solicitude to preserve harmony restrained me from saying all I thought."705

Money, money, money! Nothing else would do! Gerry, by now, was for paying it. No answer yet comes to the American memorial delivered to Talleyrand nearly three weeks before. Marshall packs his belongings, in readiness to depart. An unnamed person706 calls on him and again presses for money; France is prevailing everywhere; the envoys had better yield; why resist the inevitable, with a thousand leagues of ocean between them and home? Marshall answers blandly but crushingly.

Again Talleyrand's clerk sees Gerry. The three Americans that night talk long and heatedly. Marshall opposes any money arrangement; Gerry urges it "very decidedly"; while Pinckney agrees with Marshall. Gerry argues long about the horrors of war, the expense, the risk. Marshall presents the justice of the American cause. Gerry reproaches Marshall with being too suspicious. Marshall patiently explains, as to a child, the real situation. Gerry again charges Marshall and Pinckney with undue suspicion. Marshall retorts that Gerry "could not answer the argument but by misstating it." The evening closes, sour and chill.707

The next night the envoys once more endlessly debate their course. Marshall finally proposes that they shall demand a personal meeting with Talleyrand on the real object of the mission. Gerry stubbornly dissents and finally yields, but indulges in long and childish discussion as to what should be said to Talleyrand, confusing the situation with every word.708 Talleyrand fixes March 2 for the interview.

The following day Marshall accidentally discovers Gerry closeted with Talleyrand's clerk, who came to ask the New Englander to attend Talleyrand "in a particular conversation." Gerry goes, but reports that nothing important occurred. Then it comes out that Talleyrand had proposed to get rid of Marshall and Pinckney and keep Gerry. Gerry admits it. Thus Marshall's forecast made three weeks earlier709 is proved to have been correct.

At last, for the first time in five months, the three envoys meet Talleyrand face to face. Pinckney opens and Talleyrand answers. Gerry suggests a method of making the loan, to which Talleyrand gives qualified assent. The interview seems at an end. Then Marshall comes forward and states the American case. There is much parrying for an hour.710

The envoys again confer. Gerry urges that their instructions permit them to meet Talleyrand's demands. He goes to Marshall's room to convince the granite-like Virginian, who would not yield. "I told him," writes Marshall, "that my judgment was not more perfectly convinced that the floor was wood or that I stood on my feet and not on my head than that our instructions would not permit us to make the loan required."711 Let Gerry or Marshall or both together return to America and get new instructions if a loan must be made.

Two days later, another long and absurd discussion with Gerry occurs. Before the envoys go to see Talleyrand the next day, Gerry proposes to Marshall that, with reference to President Adams's speech, the envoys should declare, in any treaty made, "that the complaints of the two governments had been founded in mistake." Marshall hotly retorts: "With my view of things, I should tell an absolute lye if I should say that our complaints were founded in mistake. He [Gerry] replied hastily and with warmth that he wished to God, I would propose something which was accommodating: that I would propose nothing myself and objected to every thing which he proposed. I observed that it was not worth while to talk in that manner: that it was calculated to wound but not to do good: that I had proposed every thing which in my opinion was calculated to accommodate differences on just and reasonable grounds. He said that … to talk about justice was saying nothing: that I should involve our country in a war and should bring it about in such a manner, as to divide the people among themselves. I felt a momentary irritation, which I afterwards regretted, and told Mr. Gerry that I was not accustomed to such language and did not permit myself to use it with respect to him or his opinions."

Nevertheless, Marshall, with characteristic patience, once more begins to detail his reasons. Gerry interrupts – Marshall "might think of him [Gerry] as I [he] pleased." Marshall answers moderately. Gerry softens and "the conversation thus ended."712

Immediately after the bout between Marshall and Gerry the envoys saw Talleyrand for a third time. Marshall was dominant at this interview, his personality being, apparently, stronger even than his words. These were strong enough – they were, bluntly, that the envoys could not and would not accept Talleyrand's proposals.

A week later Marshall's client, Beaumarchais, called on his American attorney with the alarming news that "the effects of all Americans in France were to be Sequestered." Pay the Government money and avoid this fell event, was Beaumarchais's advice; he would see Talleyrand and call again. "Mr. Beaumarchais called on me late last evening," chronicles Marshall. "He had just parted from the Minister. He informed me that he had been told confidentially … that the Directory were determined to give passports to General Pinckney and myself but to retain Mr. Gerry." But Talleyrand would hold the order back for "a few days to give us time to make propositions conforming to the views of the Government," which "if not made Mr. Talleyrand would be compelled to execute the order."

"I told him," writes Marshall, "that if the proposition … was a loan it was perfectly unnecessary to keep it [the order] up [back] a single day: that the subject had been considered for five months" and that the envoys would not change; "that for myself, if it were impossible to effect the objects of our mission, I did not wish to stay another day in France and would as cheerfully depart the next day as at any other time."713

Beaumarchais argued and appealed. Of course, France's demand was not just – Talleyrand did not say it was; but "a compliance would be useful to our country [America]." "France," said Beaumarchais, "thought herself sufficiently powerful to give the law to the world and exacted from all around her money to enable her to finish successfully her war against England."

Finally, Beaumarchais, finding Marshall flint, "hinted" that the envoys themselves should propose which one of them should remain in France, Gerry being the choice of Talleyrand. Marshall countered. If two were to return for instructions, the envoys would decide that for themselves. If France was to choose, Marshall would have nothing to do with it.

"General Pinckney and myself and especially me," said Marshall, "were considered as being sold to the English." Beaumarchais admitted "that our positive refusal to comply with the demands of France was attributed principally to me who was considered as entirely English… I felt some little resentment and answered that the French Government thought no such thing; that neither the government nor any man in France thought me English: but they knew I was not French: they knew I would not sacrifice my duty and the interest of my country to any nation on earth, and therefore I was not a proper man to stay, and was branded with the epithet of being English: that the government knew very well I loved my own country exclusively, and it was impossible to suppose any man who loved America, fool enough to wish to engage her in a war with France if that war was avoidable."

Thus Marshall asserted his purely American attitude. It was a daring thing to do, considering the temper of the times and the place where he then was. Even in America, at that period, any one who was exclusively American and, therefore, neutral, as between the European belligerents, was denounced as being British at heart. Only by favoring France could abuse be avoided. And to assert Neutrality in the French Capital was, of course, even more dangerous than to take this American stand in the United States.

But Beaumarchais persisted and proposed to take passage with his attorney to America; not on a public mission, of course (though he had hinted at wishing to "reconcile" the two governments), but merely "to testify," writes Marshall, "to the moderation of my conduct and to the solicitude I had uniformly expressed to prevent a rupture with France."

Beaumarchais "hinted very plainly," continues Marshall, "at what he had before observed that means would be employed to irritate the people of the United States against me and that those means would be successful. I told him that I was much obliged to him but that I relied entirely on my conduct itself for its justification and that I felt no sort of apprehension for consequences, as they regarded me personally; that in public life considerations of that sort never had and never would in any degree influence me. We parted with a request, on his part, that, whatever might arise, we would preserve the most perfect temper, and with my assuring him of my persuasion that our conduct would always manifest the firmness of men who were determined, and never the violence of passionate men."

"I have been particular," concludes Marshall, "in stating this conversation, because I have no doubt of its having been held at the instance of the Minister [Talleyrand] and that it will be faithfully reported to him. I mentioned to-day to Mr. Gerry that the Government wished to detain him and send away General Pinckney and myself. He said he would not stay; but I find I shall not succeed in my efforts to procure a Serious demand of passports for Mr. Gerry and myself."714

During his efforts to keep Gerry from dangerously compromising the American case, and while waiting for Talleyrand to reply to his memorial, Marshall again writes to Washington a letter giving a survey of the war-riven and intricate European situation. He tells Washington that, "before this reaches you it will be known universally in America715 that scarcely a hope remains of" honorable adjustment of differences between France and America; that the envoys have not been and will not be "recognized" without "acceding to the demands of France … for money – to be used in the prosecution of the present war"; that according to "reports," when the Directory makes certain that the envoys "will not add a loan to the mass of American property already in the hands of this [French] government, they will be ordered out of France and a nominal [formally declared] as well as actual war will be commenc'd against the United States."716

Marshall goes on to say that his "own opinion has always been that this depends on the state of war with England"; the French are absorbed in their expected attack on Great Britain; "and it is perhaps justly believed that on this issue is stak'd the independence of Europe and America." He informs Washington of "the immense preparations for an invasion" of England; the "numerous and veteran army lining the coast"; the current statement that if "50,000 men can be" landed "no force in England will be able to resist them"; the belief that "a formidable and organized party exists in Britain, ready, so soon as a landing shall be effected, to rise and demand a reform"; the supposition that England then "will be in … the situation of the batavian and cisalpine republics and that its wealth, its commerce, and its fleets will be at the disposition of this [French] government."

But, he continues, "this expedition is not without its hazards. An army which, arriving safe, would sink England, may itself be … sunk in the channel… The effect of such a disaster on a nation already tir'd of the war and groaning under … enormous taxation" and, intimates Marshall, none too warm toward the "existing arrangements … might be extremely serious to those who hold the reins of government" in France. Many intelligent people therefore think, he says, that the "formidable military preparations" for the invasion of England "cover and favor secret negotiations for peace." This view Marshall himself entertains.

He then briefly informs Washington of Bonaparte's arrangement with Austria and Prussia which will "take from England, the hope of once more arming" those countries "in her favor," "influence the secret [French] negotiations with England," and greatly affect "Swisserland." Marshall then gives an extended account of the doings and purposes of the French in Switzerland, and refers to revolutionary activities in Sardinia, Naples, and Spain.

But notwithstanding the obstacles in its way, he concludes that "the existing [French] government … needs only money to enable it to effect all its objects. A numerous brave and well disciplined army seems to be devoted to it. The most military and the most powerful nation on earth [the French] is entirely at its disposal.717 Spain, Italy, and Holland, with the Hanseatic towns, obey its mandates."

But, says he, it is hard to "procure funds to work this vast machine. Credit being annihilated … the enormous contributions made by foreign nations," together with the revenue from imposts, are not enough to meet the expenses; and, therefore, "France is overwhelmed with taxes. The proprietor complains that his estate yields him nothing. Real property pays in taxes nearly a third of its produce and is greatly reduc'd in its price."718

While Marshall was thus engaged in studying French conditions and writing his long and careful report to Washington, Talleyrand was in no hurry to reply to the American memorial. Indeed, he did not answer until March 18, 1798, more than six weeks after receiving it. The French statement reached Marshall and Pinckney by Gerry's hands, two days after its date. "Mr. Gerry brought in, just before dinner, a letter from the Minister of exterior relations," writes Marshall, "purporting to be an answer to our long memorial criminating in strong terms our government and ourselves, and proposing that two of us should go home leaving for the negotiation the person most acceptable to France. The person is not named but no question is entertained that Mr. Gerry is alluded to. I read the letter and gave it again to Mr. Gerry."719

The next day the three envoys together read Talleyrand's letter. Gerry protests that he had told the French Foreign Minister that he would not accept Talleyrand's proposal to stay, "That," sarcastically writes Marshall, "is probably the very reason why it was made." Talleyrand's clerk calls on Gerry the next morning, suggesting light and innocent duties if he would remain. No, theatrically exclaims Gerry, I "would sooner be thrown into the Seine."720 But Gerry remained.