полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4)

But three days afterward (October 27) the news reached Paris; and Marshall adds this postscript: "The definitive peace is made with the Emperor. You will have seen the conditions. Venice has experienced the fate of Poland. England is threatened with an invasion."628

The thunders of cannon announcing Bonaparte's success were still rolling through Paris when Talleyrand's plotters again descended upon the American envoys. Bellamy came and, Pinckney and Gerry being at the opera, saw Marshall alone. The triumph of Bonaparte was his theme. The victorious general was now ready to invade England, announced Bellamy; but "concerning America not a syllable was said."629

Already Talleyrand, sensitive as any hawk to coming changes in the political weather, had begun to insinuate himself into the confidence of the future conqueror of Europe, whose diplomatic right arm he so soon was to become. The next morning the thrifty Hottenguer again visits the envoys. Bonaparte's success in the negotiations of Campo Formio, which sealed the victories of the French arms, has alarmed Hottenguer, he declares, for the success of the American mission.

Why, he asks, have the Americans made no proposition to the Directory? That haughty body "were becoming impatient and would take a decided course in regard to America" if the envoys "could not soften them," exclaims Talleyrand's solicitous messenger. Surely the envoys can see that Bonaparte's treaty with Austria has changed everything, and that therefore the envoys themselves must change accordingly.

Exhibiting great emotion, Hottenguer asserts that the Directory have determined "that all nations should aid them [the French], or be considered and treated as enemies." Think, he cries, of the "power and violence of France." Think of the present danger the envoys are in. Think of the wisdom of "softening the Directory." But he hints that "the Directory might be made more friendly." Gain time! Gain time! Give the bribe, and gain time! the wily agent advises the Americans. Otherwise, France may declare war against America.

That would be most unfortunate, answer the envoys, but assert that the present American "situation was more ruinous than a declared war could be"; for now American "commerce was floundering unprotected." In case of war "America would protect herself."

"You do not speak to the point," Hottenguer passionately cries out; "it is money; it is expected that you will offer money."

"We have given an answer to that demand," the envoys reply.

"No," exclaims Hottenguer, "you have not! What is your answer?"

"It is no," shouts Pinckney; "no; not a sixpence!"

The persistent Hottenguer does not desist. He tells the envoys that they do not know the kind of men they are dealing with. The Directory, he insists, disregard the justice of American claims; care nothing even for the French colonies; "consider themselves as perfectly invulnerable" from the United States. Money is the only thing that will interest such terrible men. The Americans, parrying, ask whether, even if they give money, Talleyrand will furnish proofs that it will produce results. Hottenguer evades the question. A long discussion ensues.

Pay the bribe, again and again urges the irritated but tenacious go-between. Does not your Government "know that nothing is to be obtained here without money?"

"Our Government had not even suspected such a state of things," declare the amazed Americans.

"Well," answers Hottenguer, "there is not an American in Paris who could not have given that information… Hamburgh and other states of Europe were obliged to buy peace … nothing could resist" the power of France; let the envoys think of "the danger of a breach with her."630

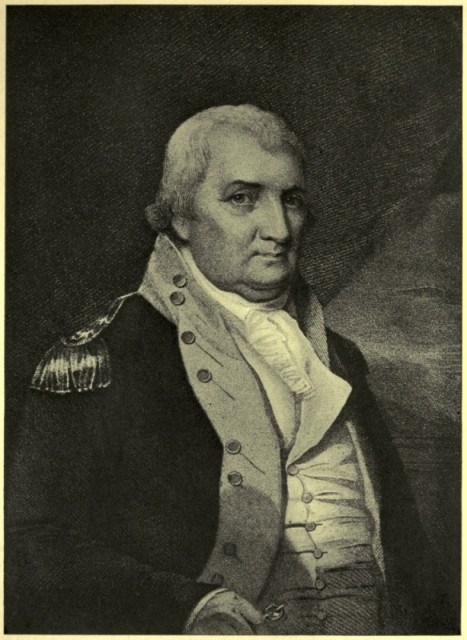

Thus far Pinckney mostly had spoken for the envoys. Marshall now took up the American case. Few utterances ever made by him more clearly reveal the mettle of the man; and none better show his conception of the American Nation's rights, dignity, and station among the Governments of the world.

CHARLES COTESWORTH PINCKNEY

"I told him [Hottenguer]," writes Marshall, "that … no nation estimated her [France's] power more highly than America or wished more to be on amicable terms with her, but that one object was still dearer to us than the friendship of France which was our national independence. That America had taken a neutral station. She had a right to take it. No nation had a right to force us out of it. That to lend … money to a belligerent power abounding in every thing requisite for war but money was to relinquish our neutrality and take part in the war. To lend this money under the lash & coercion of France was to relinquish the government of ourselves & to submit to a foreign government imposed on us by force," Marshall declared. "That we would make at least one manly struggle before we thus surrendered our national independence.

"Our case was different from that of the minor nations of Europe," he explained. "They were unable to maintain their independence & did not expect to do so. America was a great, & so far as concerned her self-defense, a powerful nation. She was able to maintain her independence & must deserve to lose it if she permitted it to be wrested from her. France & Britain have been at war for near fifty years of the last hundred & might probably be at war for fifty years of the century to come."

Marshall asserted that "America has no motives which could induce her to involve herself in those wars and that if she now preserved her neutrality & her independence it was most probable that she would not in future be afraid as she had been for four years past – but if she now surrendered her rights of self government to France or permitted them to be taken from her she could not expect to recover them or to remain neutral in any future war."631

For two hours Talleyrand's emissary pleads, threatens, bullies, argues, expostulates. Finally, he departs to consult with his fellow conspirator, or to see Talleyrand, the master of both. Thus ran the opening dialogue between the French bribe procurers and the American envoys. Day after day, week after week, the plot ran on like a play upon the stage. "A Mr. Hauteval whose fortune lay in the island of St. Domingo" called on Gerry and revealed how pained Talleyrand was that the envoys had not visited him. Again came Hauteval, whom Marshall judged to be the only one of the agents "solicitous of preserving peace."

Thus far the envoys had met with the same request, that they "call upon Talleyrand at private hours." Marshall and Pinckney said that, "having been treated in a manner extremely disrespectful" to their country, they could not visit the Minister of Foreign Affairs "in the existing state of things … unless he should expressly signify his wish" to see them "& would appoint a time & place." But, says Marshall, "Mr. Gerry having known Mr. Talleyrand in Boston considered it a piece of personal respect to wait on him & said that he would do so."632

Hottenguer again calls to explain how anxious Talleyrand was to serve the envoys. Make "one more effort," he urges, "to enable him to do so." Bonaparte's daring plan for the invasion of England was under way and Hottenguer makes the most of this. "The power and haughtiness of France," the inevitable destruction of England, the terrible consequences to America, are revealed to the Americans. "Pay by way of fees" the two hundred and fifty thousand dollar bribe, and the Directory would allow the envoys to stay in Paris; Talleyrand would then even consent to receive them while one of them went to America for instructions.633

Why hesitate? It was the usual thing; the Portuguese Minister had been dealt with in similar fashion, argues Hottenguer. The envoys counter by asking whether American vessels will meanwhile be restored to their owners. They will not, was the answer. Will the Directory stop further outrages on American commerce, ask the envoys? Of course not, exclaims Hottenguer. We do "not so much regard a little money as [you] said," declare the envoys, "although we should hazard ourselves by giving it but we see only evidences of the most extreme hostility to us." Thereupon they go into a long and useless explanation of the American case.

Gerry's visit to his "old friend" Talleyrand was fruitless; the Foreign Minister would not receive him.634 Gerry persisted, nevertheless, and finally found the French diplomat at home. Talleyrand demanded the loan, and held a new decree of the Directory before Gerry, but proposed to withhold it for a week so that the Americans could think it over. Gerry hastened to his colleagues with the news. Marshall and Pinckney told Hauteval to inform Talleyrand "that unless there is a hope that the Directory itself might be prevailed upon by reason to alter its arrêté, we do not wish to suspend it for an instant."635

The next evening, when Marshall and Pinckney were away from their quarters, Bellamy and Hottenguer called on Gerry, who again invited them to breakfast. This time Bellamy disclosed the fact that Talleyrand was now intimately connected with Bonaparte and the army in Italy. Let Gerry ponder over that! "The fate of Venice was one which might befall the United States," exclaimed Talleyrand's mouthpiece; and let Gerry not permit Marshall and Pinckney to deceive themselves by expecting help from England – France could and would attend to England, invade her, break her, force her to peace. Where then would America be? Thus for an hour Bellamy and Hottenguer worked on Gerry.636

Far as Talleyrand's agents had gone in trying to force the envoys to offer a bribe of a quarter of a million dollars, to the Foreign Minister and Directory, they now went still further. The door of the chamber of horrors was now opened wide to the stubborn Americans. Personal violence was intimated; war was threatened. But Marshall and Pinckney refused to be frightened.

The Directory, Talleyrand, and their emissaries, however, had not employed their strongest resource. "Perhaps you believe," said Bellamy to the envoys, "that in returning and exposing to your countrymen the unreasonableness of the demands of this government, you will unite them in their resistance to those demands. You are mistaken; you ought to know that the diplomatic skill of France and the means she possesses in your country are sufficient to enable her, with the French party in America,637 to throw the blame which will attend the rupture of the negotiations on the federalists, as you term yourselves, but on the British party as France terms you. And you may assure yourselves that this will be done."638

Thus it was out at last. This was the hidden card that Talleyrand had been keeping back. And it was a trump. Talleyrand managed to have it played again by a fairer hand before the game was over. Yes, surely; here was something to give the obstinate Marshall pause. For the envoys knew it to be true. There was a French party in America, and there could be little doubt that it was constantly growing stronger.639 Genêt's reception had made that plain. The outbursts throughout America of enthusiasm for France had shown it. The popular passion exhibited, when the Jay Treaty was made public, had proved it. Adams's narrow escape from defeat had demonstrated the strength of French sympathy in America.

A far more dangerous circumstance, as well known to Talleyrand as it was to the envoys, made the matter still more serious – the democratic societies, which, as we have seen, had been organized in great numbers throughout the United States had pushed the French propaganda with zeal, system, and ability; and were, to America, what the Jacobin Clubs had been to France before their bloody excesses. They had already incited armed resistance to the Government of the United States.640 Thorough information of the state of things in the young country across the ocean had emboldened Barras, upon taking leave of Monroe, to make a direct appeal to the American people in disregard of their own Government, and, indeed, almost openly against it. The threat, by Talleyrand's agents, of the force which France could exert in America, was thoroughly understood by the envoys. For, as we have seen, there was a French party in America – "a party," as Washington declared, "determined to advocate French measures under all circumstances."641 It was common knowledge among all the representatives of the American Government in Europe that the French Directory depended upon the Republican Party in this country. "They reckon … upon many friends and partisans among us," wrote the American Minister in London to the American Minister at The Hague.642

The Directory even had its particular agents in the United States to inflame the American people against their own Government if it did not yield to French demands. Weeks before the President, in 1797, had called Congress in special session on French affairs, "the active and incessant manœuvres of French agents in" America made William Smith think that any favorable action of France "will drive the great mass of knaves & fools back into her [France's] arms," notwithstanding her piracies upon our ships.643

On November 1 the envoys again decided to "hold no more indirect intercourse with" Talleyrand or the Directory. Marshall and Pinckney told Hottenguer that they thought it "degrading our country to carry on further such an indirect intercourse"; and that they "would receive no propositions" except from persons having "acknowledged authority." After much parrying, Hottenguer again unparked the batteries of the French party in America.

He told Marshall and Pinckney that "intelligence had been received from the United States, that if Colonel Burr and Mr. Madison had constituted the Mission, the difference between the two nations would have been accommodated before this time." Talleyrand was even preparing to send a memorial to America, threatened Hottenguer, complaining that the envoys were "unfriendly to an accommodation with France."

The insulted envoys hotly answered that Talleyrand's "correspondents in America took a good deal on themselves when they undertook to say how the Directory would have received Colonel Burr and Mr. Madison"; and they defied Talleyrand to send a memorial to the United States.644

Disgusted with these indirect and furtive methods, Marshall insisted on writing Talleyrand on the subject that the envoys had been sent to France to settle. "I had been for some time extremely solicitous" that such a letter should be sent, says Marshall. "It appears to me that for three envoys extraordinary to be kept in Paris thirty days without being received can only be designed to degrade & humiliate their country & to postpone a consideration of its just & reasonable complaints till future events in which it ought not to be implicated shall have determined France in her conduct towards it. Mr. Gerry had been of a contrary opinion & we had yielded to him but this evening he consented that the letter should be prepared."645

Nevertheless Gerry again objected.646 At last the Paris newspapers took a hand. "It was now in the power of the Administration [Directory]," says Marshall, "to circulate by means of an enslaved press precisely those opinions which are agreeable to itself & no printer dares to publish an examination of them."

"With this tremendous engine at its will, it [the Directory] almost absolutely controls public opinion on every subject which does not immediately affect the interior of the nation. With respect to its designs against America it experiences not so much difficulty as … would have been experienced had not our own countrymen labored to persuade them that our Government was under a British influence."647

On November 3, Marshall writes Charles Lee: "When I clos'd my last letter I did not expect to address you again from this place. I calculated on being by this time on my return to the United States… My own opinion is that France wishes to retain America in her present situation until her negotiation with Britain, which it is believed is about to recommence, shall have been terminated, and a present absolute rupture with America might encourage England to continue the war and peace with England … will put us more in her [France's] power… Our situation is more intricate and difficult than you can believe… The demand for money has been again repeated. The last address to us … concluded … that the French party in America would throw all the blame of a rupture on the federalists… We were warned of the fate of Venice. All these conversations are preparing for a public letter but the delay and the necessity of writing only in cypher prevents our sending it by this occasion… I wish you could … address the Minister concerning our reception. We despair of doing anything… Mr. Putnam an American citizen has been arrested and sent to jail under the pretext of his cheating frenchmen… This … is a mere pretext. It is considered as ominous toward Americans generally. He like most of them is a creditor of the [French] government."648

Finally the envoys sent Talleyrand the formal request, written by Marshall,649 that the Directory receive them. Talleyrand ignored it. Ten more days went by. When might they expect an answer? inquired the envoys. Talleyrand parried and delayed. "We are not yet received," wrote the envoys to Secretary of State Pickering, "and the condemnation of our vessels … is unremittingly continued. Frequent and urgent attempts have been made to inveigle us again into negotiations with persons not officially authorized, of which the obtaining of money is the basis; but we have persisted in declining to have any further communication relative to diplomatic business with persons of that description."650

Anxious as Marshall was about the business of his mission, which now rapidly was becoming an intellectual duel between Talleyrand and himself, he was far more concerned as to the health of his wife, from whom he had heard nothing since leaving America. Marshall writes her a letter full of apprehension, but lightens it with a vague account of the amusements, distractions, and dissipations of the French Capital.

"I have not, since my departure from the United States," Marshall tells his wife, "received a single letter from you or from any one of my friends in America. Judge what anxiety I must feel concerning you. I do not permit myself for a moment to suspect that you are in any degree to blame for this. I am sure you have written often to me but unhappily for me your letters have not found me. I fear they will not. They have been thrown over board or intercepted. Such is the fate of the greater number of the letters addressed by Americans to their friends in France, such I fear will be the fate of all that may be address'd to me.

"In my last letter I informed you that I counted on being at home in March. I then expected to have been able to leave this country by christmas at furthest & such is my impatience to see you & my dear children that I had determined to risk a winter passage." He asks his wife to request Mr. Wickham to see that one of Marshall's law cases "may ly till my return. I think nothing will prevent my being at the chancery term in May.

"Oh God," cries Marshall, "how much time & how much happiness have I thrown away! Paris presents one incessant round of amusement & dissipation but very little I believe even for its inhabitants of that society which interests the heart. Every day you may see something new magnificent & beautiful, every night you may see a spectacle which astonishes & enchants the imagination. The most lively fancy aided by the strongest description cannot equal the reality of the opera. All that you can conceive & a great deal more than you can conceive in the line of amusement is to be found in this gay metropolis but I suspect it would not be easy to find a friend.

"I would not live in Paris," Marshall tells his "dearest Polly" "[if I could] … be among the wealthiest of its citizens. I have changed my lodging much for the better. I liv'd till within a few days in a house where I kept my own apartments perfectly in the style of a miserable old bachelor without any mixture of female society. I now have rooms in the house of a very accomplished a very sensible & I believe a very amiable Lady whose temper, very contrary to the general character of her country women, is domestic & who generally sits with us two or three hours in the afternoon.

"This renders my situation less unpleasant than it has been but nothing can make it eligible. Let me see you once more & I … can venture to assert that no consideration would induce me ever again to consent to place the Atlantic between us. Adieu my dearest Polly. Preserve your health & be happy as possible till the return of him who is ever yours."651

The American Minister in London was following anxiously the fortunes of our envoys in Paris, and gave them frequent information and sound advice. Upon learning of their experiences, King writes that "I will not allow myself yet to despair of your success, though my apprehensions are greater than my hopes." King enclosed his Dispatch number 52 to the American Secretary of State, which tells of the Portuguese Treaty and the decline of Spain's power in Paris.652

In reply, Pinckney writes King, on December 14, that the Directory "are undoubtedly hostile to our Government, and are determined, if possible, to effectuate a change in our administration, and to oblige our present President [Adams] to resign," and further adds that the French authorities contemplate expelling from France "every American who could not prove" that he was for France and against America.

"Attempts," he continues, "are made to divide the Envoys and with that view some civilities are shown to Mr. G.[erry] and none to the two others [Marshall and Pinckney]… The American Jacobins here pay him [Gerry] great Court."653 The little New Englander already was yielding to the seductions of Talleyrand, and was also responsive to the flattery of a group of unpatriotic Americans in Paris who were buttering their own bread by playing into the hands of the Directory and the French Foreign Office.

Marshall now beheld a stage of what he believed was the natural development of unregulated democracy. Dramatic events convinced him that he was witnessing the growth of license into absolutism. Early in December Bonaparte arrived in Paris. Swiftly the Conqueror had come from Rastadt, traveling through France incognito, after one of his lightning-flash speeches to his soldiers reminding them of "the Kings whom you have vanquished, the people upon whom you have conferred liberty." The young general's name was on every tongue.

Paris was on fire to see and worship the hero. But Bonaparte kept aloof from the populace. He made himself the child of mystery. The future Emperor of the French, clad in the garments of a plain citizen, slipped unnoticed through the crowds. He would meet nobody but scholars and savants of world renown. These he courted; but he took care that this fact was known to the people. In this course he continued until the stage was set and the cue for his entrance given.

Finally the people's yearning to behold and pay homage to their soldier-statesman becomes a passion not to be denied. The envious but servile Directory yield, and on December 10, 1797, a splendid festival in Bonaparte's honor is held at the Luxembourg. The scene flames with color: captured battle-flags as decorations; the members of the Directory appareled as Roman Consuls; foreign ministers in their diplomatic costumes; officers in their uniforms; women brilliantly attired in the height of fashion.654 At last the victorious general appears on the arm of Talleyrand, the latter gorgeously clad in the dress of his high office; but Bonaparte, short, slender, and delicate, wearing the plainest clothes of the simplest citizen.

Upon this superb play-acting John Marshall looked with placid wonder. Here, then, thought this Virginian, who had himself fought for liberty on many a battlefield, were the first fruits of French revolutionary republicanism. Marshall beheld no devotion here to equal laws which should shield all men, but only adoration of the sword-wielder who was strong enough to rule all men. In the fragile, eagle-faced little warrior,655 Marshall already saw the man on horseback advancing out of the future; and in the thunders of applause he already heard the sound of marching armies, the roar of shotted guns, the huzzas of charging squadrons.