полная версия

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4)

Marshall is already bored with the social life of Philadelphia. "I am beyond expression impatient to set out on the embassy," he informs his wife. "The life I lead here does not suit me I am weary of it I dine out every day & am now engaged longer I hope than I shall stay. This dissipated life does not long suit my temper. I like it very well for a day or two but I begin to require a frugal repast with good cold water" – There was too much wine, it would seem, at Philadelphia to suit Marshall.

"I would give a great deal to dine with you to day on a piece of cold meat with our boys beside us to see Little Mary running backwards & forwards over the floor playing the sweet little tricks she [is] full of… I wish to Heaven the time which must intervene before I can repass these delightful scenes was now terminated & that we were looking back on our separation instead of seeing it before us. Farewell my dearest Polly. Make yourself happy & you will bless your ever affectionate

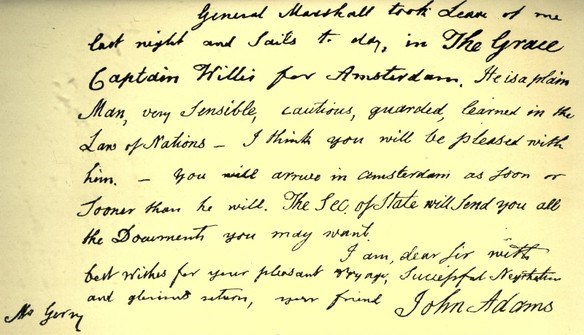

"J. Marshall."551If Marshall was pleased with Adams, the President was equally impressed with his Virginia envoy to France. "He [Marshall] is a plain man very sensible, cautious, guarded, and learned in the law of nations.552 I think you will be pleased with him,"553 Adams writes Gerry, who was to be Marshall's associate and whose capacity for the task even his intimate personal friend, the President, already distrusted. Hamilton was also in Philadelphia at the time554– a circumstance which may or may not have been significant. It was, however, the first time, so far as definite evidence attests, that these men had met since they had been comrades and fellow officers in the Revolution.

The "Aurora," the leading Republican newspaper, was mildly sarcastic over Marshall's ignorance of the French language and general lack of equipment for his diplomatic task. "Mr. Marshall, one of our extra envoys to France, will be eminently qualified for the mission by the time he reaches that country," says the "Aurora." Some official of great legal learning was coaching Marshall, it seems, and advised him to read certain monarchical books on the old France and on the fate of the ancient republics.

The "Aurora" asks "whether some history of France since the overthrow of the Monarchy would not have been more instructive to Mr. Marshall. The Envoy, however," continues the "Aurora," "approved the choice of his sagacious friend, but very shrewdly observed 'that he must first purchase Chambaud's grammar, English and French.' We understand that he is a very apt scholar, and no doubt, during the passage, he will be able to acquire enough of the French jargon for all the purposes of the embassy."555

Having received thirty-five hundred dollars for his expenses,556 Marshall set sail on the brig Grace for Amsterdam where Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the expelled American Minister to France and head of the mission, awaited him. As the land faded, Marshall wrote, like any love-sick youth, another letter to his wife which he sent back by the pilot.

"The land is just escaping from my view," writes Marshall to his "dearest Polly"; "the pilot is about to leave us & I hasten from the deck into the cabin once more to give myself the sweet indulgence of writing to you… There has been so little wind that we are not yet entirely out of the bay. It is so wide however that the land has the appearance of a light blue cloud on the surface of the water & we shall very soon lose it entirely."

Marshall assures his wife that his "cabin is neat & clean. My berth a commodious one in which I have my own bed & sheets of which I have a plenty so that I lodge as conveniently as I could do in any place whatever & I find I sleep very soundly altho on water." He is careful to say that he has plenty of creature comforts. "We have for the voyage, the greatest plenty of salt provisions live stock & poultry & as we lay in our own liquors I have taken care to provide myself with a plenty of excellent porter wine & brandy. The Captain is one of the most obliging men in the world & the vessel is said by every body to be a very fine one."

There were passengers, too, who suited Marshall's sociable disposition and who were "well disposed to make the voyage agreeable… I have then my dearest Polly every prospect before me of a passage such as I could wish in every respect but one … fear of a lengthy passage. We have met in the bay several vessels. One from Liverpool had been at sea nine weeks, & the others from other places had been proportionately long… I shall be extremely impatient to hear from you & our dear children."

Marshall tells his wife how to direct her letters to him, "some … by the way of London to the care of Rufus King esquire our Minister there, some by the way of Amsterdam or the Hague to the care of William Vanns [sic] Murr[a]y esquire our Minister at the Hague & perhaps some directed to me as Envoy extraordinary of the United States to the French Republic at Paris.

"Do not I entreat you omit to write. Some of your letters may miscarry but some will reach me & my heart can feel till my return no pleasure comparable to what will be given it by a line from you telling me that all remains well. Farewell my dearest wife. Your happiness will ever be the first prayer of your unceasingly affectionate

"J. Marshall."557So fared forth John Marshall upon the adventure which was to open the door to that historic career that lay just beyond it; and force him, against his will and his life's plans, to pass through it. But for this French mission, it is certain that Marshall's life would have been devoted to his law practice and his private affairs. He now was sailing to meet the ablest and most cunning diplomatic mind in the contemporary world whose talents, however, were as yet known to but few; and to face the most venal and ruthless governing body of any which then directed the affairs of the nations of Europe. Unguessed and unexpected by the kindly, naïve, and inexperienced Richmond lawyer were the scenes about to unroll before him; and the manner of his meeting the emergencies so soon to confront him was the passing of the great divide in his destiny.

Even had the French rulers been perfectly honest and simple men, the American envoys would have had no easy task. For American-French affairs were sadly tangled and involved. Gouverneur Morris, our first Minister to France under the Constitution, had made himself unwelcome to the French Revolutionists; and to placate the authorities then reigning in Paris, Washington had recalled Morris and appointed Monroe in his place "after several attempts had failed to obtain a more eligible character."558

Monroe, a partisan of the Revolutionists, had begun his mission with theatrical blunders; and these he continued until his recall,559 when he climaxed his imprudent conduct by his attack on Washington.560 During most of his mission Monroe was under the influence of Thomas Paine,561 who had then become the venomous enemy of Washington.

Monroe had refused to receive from his fellow Minister to England, John Jay, "confidential informal statements" as to the British treaty which Jay prudently had sent him by word of mouth only. When the Jay Treaty itself arrived, Monroe publicly denounced the treaty as "shameful,"562 a grave indiscretion in the diplomatic representative of the Government that had negotiated the offending compact.

Finally Monroe was recalled and Washington, after having offered the French mission to John Marshall, appointed Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina as his successor. The French Revolutionary authorities had bitterly resented the Jay compact, accused the American Government of violating its treaty with France, denounced the United States for ingratitude, and abused it for undue friendship to Great Britain.

In all this the French Directory had been and still was backed up by the Republicans in the United States, who, long before this, had become a distinctly French party. Thomas Paine understated the case when he described "the Republican party in the United States" as "that party which is the sincere ally of France."563

The French Republic was showing its resentment by encouraging a piratical warfare by French privateers upon American commerce. Indeed, vessels of the French Government joined in these depredations. In this way, it thought to frighten the United States into taking the armed side of France against Great Britain. The French Republic was emulating the recent outrages of that Power; and, except that the French did not impress Americans into their service, as the British had done, their Government was furnishing to America the same cause for war that Great Britain had so brutally afforded.

In less than a year and a half before Marshall sailed from Philadelphia, more than three hundred and forty American vessels had been taken by French privateers.564 Over fifty-five million dollars' worth of American property had been destroyed or confiscated under the decrees of the Directory.565 American seamen, captured on the high seas, had been beaten and imprisoned. The officers and crew of a French armed brig tortured Captain Walker, of the American ship Cincinnatus, four hours by thumbscrews.566

When Monroe learned that Pinckney had been appointed to succeed him, he began a course of insinuations to his French friends against his successor; branded Pinckney as an "aristocrat"; and thus sowed the seeds for the insulting treatment the latter received upon his appearance at the French Capital.567 Upon Pinckney's arrival, the French Directory refused to receive him, threatened him with arrest by the Paris police, and finally ordered the new American Minister out of the territory of the Republic.568

To emphasize this affront, the Directory made a great ado over the departure of Monroe, who responded with a characteristic address. To this speech Barras, then President of the Directory, replied in a harangue insulting to the American Government; it was, indeed, an open appeal to the American people to repudiate their own Administration,569 of the same character as, and no less offensive than, the verbal performances of Genêt.

And still the outrages of French privateers on American ships continued with increasing fury.570 The news of Pinckney's treatment and the speech of Barras reached America after Adams's inauguration. The President promptly called Congress into a special session and delivered to the National Legislature an address in which Adams appears at his best.

The "refusal [by the Directory] … to receive him [Pinckney] until we had acceded to their demands without discussion and without investigation, is to treat us neither as allies nor as friends, nor as a sovereign state," said the President; who continued: —

"The speech of the President [Barras] discloses sentiments more alarming than the refusal of a minister [Pinckney], because more dangerous to our independence and union…

"It evinces a disposition to separate the people of the United States from the government, to persuade them that they have different affections, principles and interests from those of their fellow citizens whom they themselves have chosen to manage their common concerns and thus to produce divisions fatal to our peace.

"Such attempts ought to be repelled with a decision which shall convince France and the world that we are not a degraded people, humiliated under a colonial spirit of fear and sense of inferiority, fitted to be the miserable instruments of foreign influence, and regardless of national honor, character, and interest.

"I should have been happy to have thrown a veil over these transactions if it had been possible to conceal them; but they have passed on the great theatre of the world, in the face of all Europe and America, and with such circumstances of publicity and solemnity that they cannot be disguised and will not soon be forgotten. They have inflicted a wound in the American breast. It is my sincere desire, however, that it may be healed."

Nevertheless, so anxious was President Adams for peace that he informed Congress: "I shall institute a fresh attempt at negotiation… If we have committed errors, and these can be demonstrated, we shall be willing to correct them; if we have done injuries, we shall be willing on conviction to redress them; and equal measures of justice we have a right to expect from France and every other nation."571

Adams took this wise action against the judgment of the Federalist leaders,572 who thought that, since the outrages upon American commerce had been committed by France and the formal insult to our Minister had been perpetrated by France, the advances should come from the offending Government. Technically, they were right; practically, they were wrong. Adams's action was sound as well as noble statesmanship.

Thus came about the extraordinary mission, of which Marshall was a member, to adjust our differences with the French Republic. The President had taken great care in selecting the envoys. He had considered Hamilton, Jefferson, and Madison,573 for this delicate and fateful business; but the two latter, for reasons of practical politics, would not serve, and without one of them, Hamilton's appointment was impossible. Pinckney, waiting at Amsterdam, was, of course, to head the commission. Finally Adams's choice fell on John Marshall of Virginia and Francis Dana, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Massachusetts; and these nominations were confirmed by the Senate.574

But Dana declined,575 and, against the unanimous advice of his Cabinet,576 Adams then nominated Elbridge Gerry, who, though a Republican, had, on account of their personal relations, voted for Adams for President, apologizing, however, most humbly to Jefferson for having done so.577

No appointment could have better pleased that unrivaled politician. Gerry was in general agreement with Jefferson and was, temperamentally, an easy instrument for craft to play upon. When Gerry hesitated to accept, Jefferson wrote his "dear friend" that "it was with infinite joy to me that you were yesterday announced to the Senate" as one of the envoys; and he pleaded with Gerry to undertake the mission.578

The leaders of the President's party in Congress greatly deplored the selection of Gerry. "No appointment could … have been more injudicious," declared Sedgwick.579 "If, sir, it was a desirable thing to distract the mission, a fitter person could not, perhaps, be found. It is ten to one against his agreeing with his colleagues," the Secretary of War advised the President.580 Indeed, Adams himself was uneasy about Gerry, and in a prophetic letter sought to forestall the very indiscretions which the latter afterwards committed.

PART OF LETTER OF JULY 17, 1797, FROM JOHN ADAMS TO ELBRIDGE GERRY DESCRIBING JOHN MARSHALL

(Facsimile)

"There is the utmost necessity for harmony, complaisance, and condescension among the three envoys, and unanimity is of great importance," the President cautioned Gerry. "It is," said Adams, "my sincere desire that an accommodation may take place; but our national faith, and the honor of our government, cannot be sacrificed. You have known enough of the unpleasant effects of disunion among ministers to convince you of the necessity of avoiding it, like a rock or quicksand… It is probable there will be manœuvres practiced to excite jealousies among you."581

Forty-eight days after Marshall took ship at Philadelphia, he arrived at The Hague.582 The long voyage had been enlivened by the sight of many vessels and the boarding of Marshall's ship three times by British men-of-war.

"Until our arrival in Holland," Marshall writes Washington, "we saw only British & neutral vessels. This added to the blockade of the dutch fleet in the Texel, of the french fleet in Brest & of the spanish fleet in Cadiz, manifests the entire dominion which one nation [Great Britain] at present possesses over the seas.

"By the ships of war which met us we were three times visited & the conduct of those who came on board was such as wou'd proceed from general orders to pursue a system calculated to conciliate America.

"Whether this be occasion'd by a sense of justice & the obligations of good faith, or solely by the hope that the perfect contrast which it exhibits to the conduct of France may excite keener sensations at that conduct, its effects on our commerce is the same."583

It was a momentous hour in French history when the Virginian landed on European soil. The French elections of 1797 had given to the conservatives a majority in the National Assembly, and the Directory was in danger. The day after Marshall reached the Dutch Capital, the troops sent by Bonaparte, that young eagle, his pinions already spread for his imperial flight, achieved the revolution of the 18th Fructidor (4th of September); gave the ballot-shaken Directory the support of bayonets; made it, in the end, the jealous but trembling tool of the youthful conqueror; and armed it with a power through which it nullified the French elections and cast into prison or drove into exile all who came under its displeasure or suspicion.

With Lodi, Arcola, and other laurels upon his brow, the Corsican already had begun his astonishing career as dictator of terms to Europe. The native Government of the Netherlands had been replaced by one modeled on the French system; and the Batavian Republic, erected by French arms, had become the vassal and the tool of Revolutionary France.

Three days after his arrival at The Hague, Marshall writes his wife of the safe ending of his voyage and how "very much pleased" he is with Pinckney, whom he "immediately saw." They were waiting "anxiously" for Gerry, Marshall tells her. "We shall wait a week or ten days longer & shall then proceed on our journey [to Paris]. You cannot conceive (yes you can conceive) how these delays perplex & mortify me. I fear I cannot return until the spring & that fear excites very much uneasiness & even regret at my having ever consented to cross the Atlantic. I wish extremely to hear from you & to know your situation. My mind clings so to Richmond that scarcely a night passes in which during the hours of sleep I have not some interesting conversation with you or concerning you."

Marshall tells his "dearest Polly" about the appearance of The Hague, its walks, buildings, and "a very extensive wood adjoining the city which extends to the sea," and which is "the pride & boast of the place." "The society at the Hague is probably very difficult, to an American it certainly is, & I have no inclination to attempt to enter into it. While the differences with France subsist the political characters of this place are probably unwilling to be found frequently in company with our countrymen. It might give umbrage to France." Pinckney had with him his wife and daughter, "who," writes Marshall, "appears to be about 12 or 13 years of age. Mrs. Pinckney informs me that only one girl of her age has visited her since the residence of the family at the Hague.584 In fact we seem to have no communication but with Americans, or those who are employed by America or who have property in our country."

While at The Hague, Marshall yields, as usual, to his love for the theater, although he cannot understand a word of the play. "Near my lodgings is a theatre in which a french company performs three times a week," he tells his wife. "I have been frequently to the play & tho' I do not understand the language I am very much amused at it. The whole company is considered as having a great deal of merit but there is a Madame de Gazor who is considered as one of the first performers in Paris who bears the palm in the estimation of every person."

Marshall narrates to his wife the result of the coup d'état of September 4. "The Directory," he writes, "with the aid of the soldiery have just put in arrest the most able & leading members of the legislature who were considered as moderate men & friends of peace. Some conjecture that this event will so abridge our negotiations as probably to occasion my return to America this fall. A speedy return is my most ardent wish but to have my return expedited by the means I have spoken of is a circumstance so calamitous that I deprecate it as the greatest of evils. Remember me affectionately to our friends & kiss for me our dear little Mary. Tell the boys how much I expect from them & how anxious I am to see them as well as their beloved mother. I am my dearest Polly unalterably your

"J Marshall."585The theaters and other attractions of The Hague left Marshall plenty of time, however, for serious and careful investigations. The result of these he details to Washington. The following letter shows not only Marshall's state of mind just before starting for Paris, but also the effect of European conditions upon him and how strongly they already were confirming Marshall's tendency of thought so firmly established by every event of his life since our War for Independence: —

"Tho' the face of the country [Holland] still exhibits a degree of wealth & population perhaps unequal'd in any other part of Europe, its decline is visible. The great city of Amsterdam is in a state of blockade. More than two thirds of its shipping lie unemploy'd in port. Other seaports suffer tho' not in so great a degree. In the meantime the requisitions made [by the French] upon them [the Dutch] are enormous…

"It is supposed that France has by various means drawn from Holland about 60,000,000 of dollars. This has been paid, in addition to the national expenditures, by a population of less than 2,000,000… Not even peace can place Holland in her former situation. Antwerp will draw from Amsterdam a large portion of that commerce which is the great source of its wealth; for Antwerp possesses, in the existing state of things, advantages which not even weight of capital can entirely surmount."

Marshall then gives Washington a clear and striking account of the political happenings among the Dutch under French domination: —

"The political divisions of this country & its uncertainty concerning its future destiny must also have their operation…

"A constitution which I have not read, but which is stated to me to have contain'd all the great fundamentals of a representative government, & which has been prepar'd with infinite labor, & has experienc'd an uncommon length of discussion was rejected in the primary assemblies by a majority of nearly five to one of those who voted…

"The substitute wish'd for by its opponents is a legislature with a single branch having power only to initiate laws which are to derive their force from the sanction of the primary assemblies. I do not know how they wou'd organize it… It is remarkable that the very men who have rejected the form of government propos'd to them have reëlected a great majority of the persons who prepar'd it & will probably make from it no essential departure… It is worthy of notice that more than two thirds of those entitled to suffrage including perhaps more than four fifths of the property of the nation & who wish'd, as I am told, the adoption of the constitution, withheld their votes…

"Many were restrain'd by an unwillingness to take the oath required before a vote could be receiv'd; many, disgusted with the present state of things, have come to the unwise determination of revenging themselves on those whom they charge with having occasion'd it by taking no part whatever in the politics of their country, & many seem to be indifferent to every consideration not immediately connected with their particular employments."

Holland's example made the deepest impression on Marshall's mind. What he saw and heard fortified his already firm purpose not to permit America, if he could help it, to become the subordinate or ally of any foreign power. The concept of the American people as a separate and independent Nation unattached to, unsupported by, and unafraid of any other country, which was growing rapidly to be the passion of Marshall's life, was given fresh force by the humiliation and distress of the Dutch under French control.

"The political opinions which have produc'd the rejection of the constitution," Marshall reasons in his report to Washington, "& which, as it wou'd seem, can only be entertain'd by intemperate & ill inform'd minds unaccustom'd to a union of the theory & practice of liberty, must be associated with a general system which if brought into action will produce the same excesses here which have been so justly deplor'd in France.