полная версия

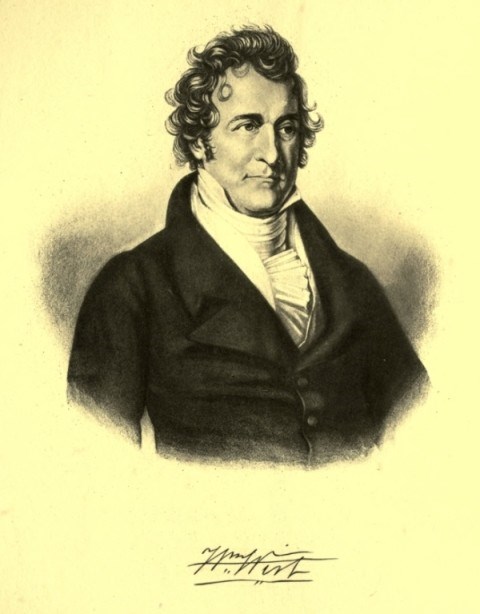

полная версияThe Life of John Marshall (Volume 2 of 4)

"He was educated for the bar," writes Schmidt, "at a period when digests, abridgments & all the numerous facilities, which now smooth the path of the law student were almost unknown & when you often sought in vain in the Reporters which usually wore the imposing form of folios, even for an index of the decisions & when marginal notes of the points determined in a case was a luxury not to be either looked for or expected.

"At this period when the principles of the Common Law had to be studied in the black-letter pages of Coke upon Littleton, a work equally remarkable for quaintness of expression, profundity of research and the absence of all method in the arrangements of its very valuable materials; when the rules of pleading had to be looked for in Chief Justice Saunders's Reports, while the doctrinal parts of the jurisprudence, based almost exclusively on the precedents had to be sought after in the reports of Dyer, Plowden, Coke, Popham … it was … no easy task to become an able lawyer & it required no common share of industry and perseverance to amass sufficient knowledge of the law to make even a decent appearance in the forum."484

It would not be strange, therefore, if Marshall did cite very few authorities in the scores of cases argued by him. But it seems certain that he would not have relied upon the "learning of the law" in any event; for at a later period, when precedents were more abundant and accessible, he still ignored them. Even in these early years other counsel exhibited the results of much research; but not so Marshall. In most of his arguments, as reported in volumes one, two, and four of Call's Virginia Reports and in volumes one and two of Washington's Virginia Reports,485 he depended on no authority whatever. Frequently when the arguments of his associates and of opposing counsel show that they had explored the whole field of legal learning on the subject in hand, Marshall referred to no precedent.486 The strongest feature of his argument was his statement of the case.

The multitude of cases which Marshall argued before the General Court of Appeals and before the High Court of Chancery at Richmond covered every possible subject of litigation at that time. He lost almost as frequently as he won. Out of one hundred and twenty-one cases reported, Marshall was on the winning side sixty-two times and on the losing side fifty times. In two cases he was partly successful and partly unsuccessful, and in seven it is impossible to tell from the reports what the outcome was.

Once Marshall appeared for clients whose cause was so weak that the court decided against him on his own argument, refusing to hear opposing counsel.487 He was extremely frank and honest with the court, and on one occasion went so far as to say that the opposing counsel was in the right and himself in the wrong.488 "My own opinion," he admitted to the court in this case, "is that the law is correctly stated by Mr. Ronald [the opposing counsel], but the point has been otherwise determined in the General Court." Marshall, of course, lost.489

Nearly all the cases in which Marshall was engaged concerned property rights. Only three or four of the controversies in which he took part involved criminal law. A considerable part of the litigation in which he was employed was intricate and involved; and in this class of cases his lucid and orderly mind made him the intellectual master of the contending lawyers. Marshall's ability to extract from the confusion of the most involved question its vital elements and to state those elements in simple terms was helpful to the court, and frankly appreciated by the judges.

Few letters of Marshall to his fellow lawyers written during this period are extant. Most of these are very brief and confined strictly to the particular cases which he had been retained by his associate attorneys throughout Virginia to conduct before the Court of Appeals. Occasionally, however, his humor breaks forth.

"I cannot appear for Donaghoe," writes Marshall to a country member of the bar who lived in the Valley over the mountains. "I do not decline his business from any objection to his bank. To that I should like very well to have free access & wou'd certainly discount from it as largely as he wou'd permit, but I am already fixed by Rankin & as those who are once in the bank do not I am told readily get out again I despair of being ever able to touch the guineas of Donaghoe.

"Shall we never see you again in Richmond? I was very much rejoiced when I heard that you were happily married but if that amounts to a ne exeat which is to confine you entirely to your side of the mountain, I shall be selfish enough to regret your good fortune & almost wish you had found some little crooked rib among the fish and oysters which would once a year drag you into this part of our terraqueous globe.

"You have forgotten I believe the solemn compact we made to take a journey to Philadelphia together this winter and superintend for a while the proceedings of Congress."490

Again, writing to Stuart concerning a libel suit, Marshall says: "Whether the truth of the libel may be justified or not is a perfectly unsettled question. If in that respect the law here varies from the law of England it must be because such is the will of their Honors for I know of no legislative act to vary it. It will however be right to appeal was it only to secure a compromise."491

Marshall's sociableness and love of play made him the leader of the Barbecue Club, consisting of thirty of the most agreeable of the prominent men in Richmond. Membership in this club was eagerly sought and difficult to secure, two negatives being sufficient to reject a candidate. Meetings were held each Saturday, in pleasant weather, at "the springs" on the farm of Mr. Buchanan, the Episcopal clergyman. There a generous meal was served and games played, quoits being the favorite sport. One such occasion of which there is a trustworthy account shows the humor, the wit, and the good-fellowship of Marshall.

He welcomed the invited guests, Messrs. Blair and Buchanan, the famous "Two Parsons" of Richmond, and then announced that a fine of a basket of champagne, imposed on two members for talking politics at a previous meeting of the club, had been paid and that the wine was at hand. It was drunk from tumblers and the Presbyterian minister joked about the danger of those who "drank from tumblers on the table becoming tumblers under the table." Marshall challenged "Parson" Blair to a game of quoits, each selecting four partners. His quoits were big, rough, heavy iron affairs that nobody else could throw, those of the other players being smaller and of polished brass. Marshall rang the meg and Blair threw his quoit directly over that of his opponent. Loud were the cries of applause and a great controversy arose as to which player had won. The decision was left to the club with the understanding that when the question was determined they should "crack another bottle of champagne."

Marshall argued his own case with great solemnity and elaboration. The one first ringing the meg must be deemed the winner, unless his adversary knocked off the first quoit and put his own in its place. This required perfection, which Blair did not possess. Blair claimed to have won by being on top of Marshall; but suppose he tried to reach heaven "by riding on my back," asked Marshall. "I fear that from my many backslidings and deficiencies, he may be badly disappointed." Blair's method was like playing leap frog, said he. And did anybody play backgammon in that way? Also there was the ancient legal maxim, "Cujus est solum, ejus est usque ad cœlum": being "the first occupant his right extended from the ground up to the vault of heaven and no one had a right to become a squatter on his back." If Blair had any claim "he must obtain a writ of ejectment or drive him [Marshall] from his position vi et armis." Marshall then cited the boys' game of marbles and, by analogy, proved that he had won and should be given the verdict of the club.

Wickham argued at length that the judgment of the club should be that "where two adversary quoits are on the same meg, neither is victorious." Marshall's quoit was so big and heavy that no ordinary quoit could move it and "no rule requires an impossibility." As to Marshall's insinuation that Blair was trying to reach "Elysium by mounting on his back," it was plain to the club that such was not the parson's intention, but that he meant only to get a more elevated view of earthly things. Also Blair, by "riding on that pinnacle," will be apt to arrive in time at the upper round of the ladder of fame. The legal maxim cited by Marshall was really against his claim, since the ground belonged to Mr. Buchanan and Marshall was as much of a "squatter" as Blair was. "The first squatter was no better than the second." And why did Marshall talk of ejecting him by force of arms? Everybody knew that "parsons are men of peace and do not vanquish their antagonists vi et armis. We do not deserve to prolong this riding on Mr. Marshall's back; he is too much of a Rosinante to make the ride agreeable." The club declined to consider seriously Marshall's comparison of the manly game of quoits with the boys' game of marbles, for had not one of the clergymen present preached a sermon on "marvel not"? There was no analogy to quoits in Marshall's citation of leap frog nor of backgammon; and Wickham closed, amid the cheers of the club, by pointing out the difference between quoits and leap frog.

The club voted with impressive gravity, taking care to make the vote as even as possible and finally determined that the disputed throw was a draw. The game was resumed and Marshall won.492

Such were Marshall's diversions when an attorney at Richmond. His "lawyer dinners" at his house,493 his card playing at Farmicola's tavern, his quoit-throwing and pleasant foolery at the Barbecue Club, and other similar amusements which served to take his mind from the grave problems on which, at other times, it was constantly working, were continued, as we shall see, and with increasing zest, after he became the world's leading jurist-statesman of his time. But neither as lawyer nor judge did these wholesome frivolities interfere with his serious work.

Marshall's first case of nation-wide interest, in which his argument gave him fame among lawyers throughout the country, was the historic controversy over the British debts. When Congress enacted the Judiciary Law of 1789 and the National Courts were established, British creditors at once began action to recover their long overdue debts. During the Revolution, other States as well as Virginia had passed laws confiscating the debts which their citizens owed British subjects and sequestering British property.

Under these laws, debtors could cancel their obligations in several ways. The Treaty of Peace between the United States and Great Britain provided, among other things, that "It is agreed that creditors on either side shall meet with no legal impediments to the recovery of the full value in sterling money of all bona fide debts heretofore contracted." The Constitution provided that "All treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every State shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding,"494 and that "The judicial power shall extend to all cases in law and equity arising under this Constitution, the laws of the United States, and treaties made, or which shall be made, under their authority; to all cases … between a State, or the citizens thereof, and foreign States citizens, or subjects."495

Thus the case of Ware, Administrator, vs. Hylton et al., which involved the validity of a State law in conflict with a treaty, attracted the attention of the whole country when finally it reached the Supreme Court. The question in that celebrated controversy was whether a State law, suspending the collection of a debt due to a subject of Great Britain, was valid as against the treaty which provided that no "legal impediment" should prevent the recovery of the obligation.

Ware vs. Hylton was a test case; and its decision involved immense sums of money. Large numbers of creditors who had sought to cancel their debts under the confiscation laws were vitally interested. Marshall, in this case, made the notable argument that carried his reputation as a lawyer beyond Virginia and won for him the admiration of the ablest men at the bar, regardless of their opinion of the merits of the controversy.

It is an example of "the irony of fate" that in this historic legal contest Marshall supported the theory which he had opposed throughout his public career thus far, and to demolish which his entire after life was given. More remarkable still, his efforts for his clients were opposed to his own interests; for, had he succeeded for those who employed him, he would have wrecked the only considerable business transaction in which he ever engaged.496 He was employed by the debtors to uphold those laws of Virginia which sequestered British property and prevented the collection of the British debts; and he put forth all his power in this behalf.

Three such cases were pending in Virginia; and these were heard twice by the National Court in Richmond as a consolidated cause, the real issue being the same in all. The second hearing was during the May Term of 1793 before Chief Justice Jay, Justice Iredell of the Supreme Court, and Judge Griffin of the United States District Court. The attorneys for the British creditors were William Ronald, John Baker, John Stark, and John Wickham. For the defendants were Alexander Campbell, James Innes, Patrick Henry, and John Marshall. Thus we see Marshall, when thirty-six years of age, after ten years of practice at the Richmond bar, interrupted as those years were by politics and legislative activities, one of the group of lawyers who, for power, brilliancy, and learning, were unsurpassed in America.

The argument at the Richmond hearing was a brilliant display of eloquence, reasoning, and erudition, and, among lawyers, its repute has reached even to the present day. Counsel on both sides exerted every ounce of their strength. When Patrick Henry had finished his appeal, Justice Iredell was so overcome that he cried, "Gracious God! He is an orator indeed!"497 The Countess of Huntingdon, who was then in Richmond and heard the arguments of all the attorneys, declared: "If every one had spoken in Westminster Hall, they would have been honored with a peerage."498

In his formal opinion, Justice Iredell thus expressed his admiration: "The cause has been spoken to, at the bar, with a degree of ability equal to any occasion… I shall as long as I live, remember with pleasure and respect the arguments which I have heard on this case: they have discovered an ingenuity, a depth of investigation, and a power of reasoning fully equal to anything I have ever witnessed… Fatigue has given way under its influence; the heart has been warmed, while the understanding has been instructed."499

Marshall's argument before the District Court of Richmond must have impressed his debtor clients more than that of any other of their distinguished counsel, with the single exception of Alexander Campbell; for when, on appeal to the Supreme Court of the United States, the case came on for hearing in 1796, we find that only Marshall and Campbell appeared for the debtors.

It is unfortunate that Marshall's argument before the Supreme Court at Philadelphia is very poorly reported. But inadequate as the report is, it still reveals the peculiar clearness and the compact and simple reasoning which made up the whole of Marshall's method, whether in legal arguments, political speeches, diplomatic letters, or judicial opinions.

Marshall argued that the Virginia law barred the recovery of the debts regardless of the treaty. "It has been conceded," said he, "that independent nations have, in general, the right to confiscation; and that Virginia, at the time of passing her law, was an independent nation." A State engaged in war has the powers of war, "and confiscation is one of those powers, weakening the party against whom it is employed and strengthening the party that employs it." Nations have equal powers; and, from July 4, 1776, America was as independent a nation as Great Britain. What would have happened if Great Britain had been victorious? "Sequestration, confiscation, and proscription would have followed in the train of that event," asserted Marshall.

Why, then, he asked, "should the confiscation of British property be deemed less just in the event of an American triumph?" Property and its disposition is not a natural right, but the "creature of civil society, and subject in all respects to the disposition and control of civil institutions." Even if "an individual has not the power of extinguishing his debts," still "the community to which he belongs … may … upon principles of public policy, prevent his creditors from recovering them." The ownership and control of property "is the offspring of the social state; not the incident of a state of nature. But the Revolution did not reduce the inhabitants of America to a state of nature; and if it did, the plaintiff's claim would be at an end." Virginia was within her rights when she confiscated these debts.

As an independent nation Virginia could do as she liked, declared Marshall. Legally, then, at the time of the Treaty of Peace in 1783, "the defendant owed nothing to the plaintiff." Did the treaty revive the debt thus extinguished? No: For the treaty provides "that creditors on either side shall meet with no lawful impediment to the recovery" of their debts. Who are the creditors? "There cannot be a creditor where there is not a debt; and the British debts were extinguished by the act of confiscation," which was entirely legal.

Plainly, then, argued Marshall, the treaty "must be construed with reference to those creditors" whose debts had not been extinguished by the sequestration laws. There were cases of such debts and it was to these only that the treaty applied. The Virginia law must have been known to the commissioners who made the treaty; and it was unthinkable that they should attempt to repeal those laws in the treaty without using plain words to that effect.

Such is an outline of Marshall's argument, as inaccurately and defectively reported.500

Cold and dry as it appears in the reporter's notes, Marshall's address to the Supreme Court made a tremendous impression on all who heard it. When he left the court-room, he was followed by admiring crowds. The ablest public men at the Capital were watching Marshall narrowly and these particularly were captivated by his argument. "His head is one of the best organized of any one that I have known," writes the keenly observant King, a year later, in giving to Pinckney his estimate of Marshall. "This I say from general Reputation, and more satisfactorily from an Argument that I heard him deliver before the fed'l Court at Philadelphia."501 King's judgment of Marshall's intellectual strength was that generally held.

Marshall's speech had a more enduring effect on those who listened to it than any other address he ever made, excepting that on the Jonathan Robins case.502 Twenty-four years afterwards William Wirt, then at the summit of his brilliant career, advising Francis Gilmer upon the art of oratory, recalled Marshall's argument in the British Debts case as an example for Gilmer to follow. Wirt thus contrasts Marshall's method with that of Campbell on the same occasion: —

"Campbell played off all his Apollonian airs; but they were lost. Marshall spoke, as he always does, to the judgment merely and for the simple purpose of convincing. Marshall was justly pronounced one of the greatest men of the country; he was followed by crowds, looked upon, and courted with every evidence of admiration and respect for the great powers of his mind. Campbell was neglected and slighted, and came home in disgust.

"Marshall's maxim seems always to have been, 'aim exclusively at Strength:' and from his eminent success, I say, if I had my life to go over again, I would practice on his maxim with the most rigorous severity, until the character of my mind was established."503

In another letter to Gilmer, Wirt again urges his son-in-law to imitate Marshall's style. In his early career Wirt had suffered in his own arguments from too much adornment which detracted from the real solidity and careful learning of his efforts at the bar. And when, finally, in his old age he had, through his own mistakes, learned the value of simplicity in statement and clear logic in argument, he counseled young Gilmer accordingly.

"In your arguments at the bar," he writes, "let argument strongly predominate. Sacrifice your flowers… Avoid as you would the gates of death, the reputation for floridity… Imitate … Marshall's simple process of reasoning."504

Following the advice of his distinguished brother-in-law, Gilmer studied Marshall with the hungry zeal of ambitious youth. Thus it is that to Francis Gilmer we owe what is perhaps the truest analysis, made by a personal observer, of Marshall's method as advocate and orator.

"So perfect is his analysis," records Gilmer, "that he extracts the whole matter, the kernel of the inquiry, unbroken, undivided, clean and entire. In this process, such is the instinctive neatness and precision of his mind that no superfluous thought, or even word, ever presents itself and still he says everything that seems appropriate to the subject.

"This perfect exemption from any unnecessary encumbrance of matter or ornament, is in some degree the effect of an aversion for the labour of thinking. So great a mind, perhaps, like large bodies in the physical world, is with difficulty set in motion. That this is the case with Mr. Marshall's is manifest, from his mode of entering on an argument both in conversation and in publick debate.

"It is difficult to rouse his faculties; he begins with reluctance, hesitation, and vacancy of eye; presently his articulation becomes less broken, his eye more fixed, until finally, his voice is full, clear, and rapid, his manner bold, and his whole face lighted up, with the mingled fires of genius and passion; and he pours forth the unbroken stream of eloquence, in a current deep, majestick, smooth, and strong.

"He reminds one of some great bird, which flounders and flounces on the earth for a while before it acquires the impetus to sustain its soaring flight.

"The characteristick of his eloquence is an irresistible cogency, and a luminous simplicity in the order of his reasoning. His arguments are remarkable for their separate and independent strength, and for the solid, compact, impenetrable order in which they are arrayed.

"He certainly possesses in an eminent degree the power which had been ascribed to him, of mastering the most complicated subjects with facility, and when moving with his full momentum, even without the appearance of resistance."

Comparing Marshall and Randolph, Gilmer says: —

"The powers of these two gentlemen are strikingly contrasted by nature. In Mr. Marshall's speeches, all is reasoning; in Mr. Randolph's everything is declamation. The former scarcely uses a figure; the latter hardly an abstraction. One is awkward; the other graceful.

"One is indifferent as to his words, and slovenly in his pronunciation; the other adapts his phrases to the sense with poetick felicity; his voice to the sound with musical exactness.

"There is no breach in the train of Mr. Marshall's thoughts; little connection between Mr. Randolph's. Each has his separate excellence, but either is far from being a finished orator."505

Another invaluable first-hand analysis of Marshall's style and manner of argument is that of William Wirt, himself, in the vivacious descriptions of "The British Spy": —

"He possesses one original, and, almost supernatural faculty, the faculty of developing a subject by a single glance of his mind, and detecting at once, the very point on which every controversy depends. No matter what the question; though ten times more knotty than 'the gnarled oak,' the lightning of heaven is not more rapid nor more resistless, than his astonishing penetration.