полная версия

полная версияHistory of the Royal Regiment of Artillery, Vol. 1

Of the gallantry of Cornwallis and his troops there has never been any question. He did not surrender until his ammunition was expended, his defences crumbled under the enemy's fire, and hope of succour completely fled. Of the gallantry of that portion of his troops in which the reader of these pages is most interested, he himself thus wrote in his official despatches: "Captain Rochfort, who commanded the Artillery, and, indeed, every officer and soldier of that distinguished Corps, have merited, in every respect, my highest approbation."

The force of Royal Artillery present at the capitulation of Yorktown amounted to 167 of all ranks. The largest number whom Lord Cornwallis had commanded during his Virginian campaign did not exceed 233, with fifty additional German Artillerymen. But, in addition to casualties before the investment of Yorktown, the loss to the Royal Artillery during the time between the 27th September and the 19th October, – the date of the capitulation, – was as follows: —

There were also nineteen sick, in addition to the wounded, on the day the garrison surrendered.

In this crowning point of the American War the defenders were as much outnumbered as Sir Henry Clinton was out-manœuvred by Washington. It is impossible to praise too highly the tactics of the latter General on this occasion. The difficulties with which he had to contend were numerous. A spirit of discontent and insubordination had been manifested during the past year among his troops; there was a Loyalist party of no mean dimensions in the South; in Pennsylvania he could reckon on few active supporters; and New York, – stronger now than ever, after six years of British occupation, – seemed hopelessly unattainable. Worse than all, however, the French Admiral was nervous, and reluctant to remain in so cramped a situation with so large a fleet. Had he carried out his threat of going to sea, instead of yielding to Washington's earnest entreaties and remonstrances, the capitulation would never have taken place. Lee's description of the scene on the day the garrison marched out is doubly interesting, as being that of a spectator: "At two o'clock in the evening the British Army, led by General O'Hara, marched out of its lines with colours cased and drums beating a British march. The author was present at the ceremony; and certainly no spectacle could be more impressive than the one now exhibited. Valiant troops yielding up their arms after fighting in defence of a cause dear to them (because the cause of their country), under a leader who, throughout the war, in every grade and in every situation to which he had been called, appeared the Hector of his host. Battle after battle had he fought; climate after climate had he endured; towns had yielded to his mandate; posts were abandoned at his approach; armies were conquered by his prowess – one nearly exterminated, another chased from the confines of South Carolina beyond the Dan into Virginia, and a third severely chastised in that State, on the shores of James River. But here even he, in the midst of his splendid career, found his conqueror.

"The road through which they marched was lined with spectators, French and American. On one side the Commander-in-chief, surrounded by his suite and the American staff, took his station; on the other side, opposite to him, was the Count de Rochambeau in like manner attended. The captive army approached, moving slowly in column with grace and precision. Universal silence was observed amidst the vast concourse, and the utmost decency prevailed; exhibiting in demeanour an awful sense of the vicissitudes of human fortune, mingled with commiseration for the unhappy… Every eye was turned, searching for the British Commander-in-chief, anxious to look at that man, heretofore so much the object of their dread. All were disappointed. Cornwallis held himself back from the humiliating scene, obeying emotions which his great character ought to have stifled. He had been unfortunate, not from any false step or deficiency of exertion on his part, but from the infatuated policy of his superior, and the united power of his enemy, brought to bear upon him alone. There was nothing with which he could reproach himself: there was nothing with which he could reproach his brave and faithful army: why not then appear at its head in the day of misfortune, as he had always done in the day of triumph? The British General in this instance deviated from his usual line of conduct, dimming the splendour of his long and brilliant career… By the official returns it appears that the besieging army, at the termination of the siege, amounted to 16,000 men, viz. 550 °Continentals, 3500 militia, and 7000 French. The British force in toto is put down at 7107; of whom only 4017 rank and file are stated to have been fit for duty."

With this misfortune virtually ends the History of the American War, – certainly as far as the Royal Artillery's services are concerned. Another year, and more, was to pass ere even the preliminaries of the Treaty of Independence should be signed; and not until 1783 was Peace officially proclaimed: but a new Government came into power in England in the beginning of 1782, one of whose political cries was "Peace with the American Colonies!"; and Rodney's glorious victory over the French fleet on the 12th April in that year made the Americans eager to meet the advances of the parent country.

Sir Henry Clinton resigned in favour of Sir Guy Carleton, and Washington remained in Philadelphia. The companies of Artillery were detailed to proceed to Canada, Nova Scotia, the West Indies, and a proportion to England, on the evacuation of New York, which took place in 1783; the Treaty of Peace having been signed on the 3rd September in that year at Versailles. The same Treaty brought peace between England and her other enemies, France and Spain, who had availed themselves of her American troubles to avenge, as they hoped, former injuries.

As far as comfort and satisfaction can be obtained from the study of an unsuccessful war, they can be got by the Royal Artilleryman in tracing the services of his Corps during the great war in America. Bravery, zeal, and readiness to endure hardship, adorn even a defeated army; and these qualities were in a high, and even eminent degree, manifested by the Royal Artillery. In the blaze of triumph which is annually renewed in America on the anniversary of their Declaration of Independence, Americans do not, it is hoped, forget that, whether England's cause was just or not, her soldiers were as brave as themselves.

A few words may here be introduced with reference to such of the officers of the Regiment as were engaged in this war, and afterwards obtained high professional reputation. A summary of their services may be taken from the valuable Appendix to Kane's List. In addition to General Pattison, whose career has already been sketched, the following officers may be mentioned: —

1. Major-General Thomas James, an officer who held a command during the early part of the War of Independence; who wrote a valuable work on Gibraltar, entitled "The Herculean Straits;" and who died in 1780, as a Colonel-Commandant.

2. Lieut. – General S. Cleaveland, an officer who has already been mentioned as having commanded the Royal Artillery during the American War, prior to the arrival of General Pattison; who had previously served in the West Indies and at the capture of the Havannah; and who died in 1794, also in the rank of Colonel-Commandant.

3. Lieut. – General F. Macbean, an officer frequently mentioned in this volume, as having been present at Fontenoy, Rocour, Laffeldt, Minden, Warberg, Fritzlar, and in Portugal. He was appointed to the command of the Royal Artillery in Canada, in 1778; was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1786; and died in 1800, as Colonel-Commandant of the Invalid Battalion.

4. Major-General W. Phillips has already been repeatedly noticed in this volume, and his death during the war already recorded.

5. General Sir A. Farrington, Bart., served in America from 1764 to 1768, and from 1773 to 1783, having been engaged in most of the engagements during the war, up to the Capture of Philadelphia, after which he commanded the Artillery in Halifax, Nova Scotia. "He commanded the Royal Artillery at Plymouth in 1788-9, at Gibraltar in 1790-1, at Woolwich 1794-7 and in Holland in 1799. He was D.C.L. of Oxford, and in consideration of his long and valued services he was created a Baronet, on the 3rd October, 1818. He served in three reigns, for the long period of sixty-eight years, being at the time of his death the oldest officer in the British service, retaining the use of his faculties, and performing the functions of his office to the last."47

6. Lieutenant-General Thomas Davies is thus mentioned in Kane's List: "He saw much service in North America during the operations connected with the conquest of Canada. At one time (while a Lieutenant) he commanded a naval force on Lake Champlain, and took a French frigate of eighteen guns after a close action of nearly three hours. Lieutenant Davies hoisted the first British flag in Montreal. He served as Captain of a Company in the most important actions of the American Revolutionary War. During his long service he had command of the Royal Artillery at Coxheath Camp; also at Gibraltar, in Canada, and at Plymouth. He was also two years Commandant of Quebec." This officer joined as a cadet in 1755, and died as a Colonel-Commandant in 1799.

7. General Sir Thomas Blomefield will receive more detailed notice when the story of the Copenhagen expedition, in 1807, comes to be written in these pages. His services during the American War are thus summarised by Kane's List: "In 1776, Captain Blomefield proceeded to America as Brigade-Major to Brigadier Phillips. Among his services at this period was the construction of floating batteries upon the Canadian Lakes; and he was actively engaged with the army under General Burgoyne until the action which preceded the unfortunate convention of Saratoga, when he was severely wounded by a musket-shot in the head. In 178 °Captain Blomefield was appointed Inspector of Artillery, and of the Brass Foundry… From this period (1783) dates the high character of British cast-iron and brass ordnance. Major-General Blomefield was selected, in 1807, to command the Artillery in the expedition to Copenhagen, and received for his services on this occasion the thanks of both Houses of Parliament and a baronetcy." He died as a Colonel-Commandant on 24th August, 1822.

8. Major-General Robert Douglas has already been mentioned for his gallantry as a subaltern during the American War. In 1795 he was appointed Commandant of the Driver Corps, an office which he held until 1817. He died at Woolwich, in 1827, as a Colonel-Commandant of a Battalion.

9. Lieutenant-General Sir John Macleod has already been mentioned in connection with the Battle of Guildford, and will receive more detailed notice in the next volume, his own history and that of his Regiment being indissolubly woven together. It may here be mentioned, however, that, "on his return from America, he was placed on the Staff of the Master-General; and from this time till his death he was employed in the important duties of the organization of the Regiment, and of the arrangement and equipment of the Artillery for all the expeditions (of which there were no fewer than eleven) during this period. He held successively the appointments of Chief of the Ordnance Staff, Deputy-Adjutant-General, and Director-General of Artillery. He commanded the Royal Artillery during the expedition to Walcheren in 1809. In 1820 George IV., desirous of marking his sense of his long and important services, conferred on him the honour of knighthood, and invested him with the Grand Cross of the Royal Guelphic Order."48 The whole of his official letter-books, during the time he was Deputy-Adjutant-General of Artillery, are deposited in the Royal Artillery Record Office, and afford a priceless historical mine to the student. His letters are distinguished by rare ability and punctilious courtesy.

10. General Sir John Smith, who had been in Canada since 1773, was taken prisoner by the rebels, at St. John's, in November, 1775. In 1777 he was exchanged, served under Sir William Howe, and was present at Brandywine Creek, Germantown, the Siege of Charlestown, and at Yorktown. He commanded the Artillery under Sir Ralph Abercromby in the West Indies in 1795; accompanied the Duke of York to Holland in 1799; and served at Gibraltar from 1804 to 1814, being Governor of the place at the conclusion of his service. He died as Colonel-Commandant in July, 1837.

Lastly may be mentioned Lieut. – General Sir Edward Howorth, one of the officers taken prisoner at Saratoga. He commanded the Royal Artillery in later years at the battles of Talavera, Busaco, and Fuentes d'Onore. He died as Colonel-Commandant of a Battalion in 1821.

The reader will now enter upon a region of statistics, which, at the date of the publication of the present work, possess a peculiar interest.

Quickened as promotion had been by the extensive active service, and proportionate number of casualties in the Regiment, between 1775 and 1782, it was still unsatisfactory; and with a future of peace, it was certain to become more so. It was necessary to introduce some remedy, and, in doing so, the Board of Ordnance adopted wisely the principle pursued in later times by the late Secretary of State for War, Mr. Cardwell, and made an organic change in the proportions of the various ranks, instead of accelerating promotion in a temporary, spasmodic way, by encouraging unnecessary, impolitic, and costly retirements. Mr. Cardwell, in 1872, when shadowing forth his views on this subject to the House of Commons, was unconsciously maturing the scheme commenced by the Ordnance in 1782 – commenced, but never completed – for the Temple of Janus was not long shut after 1783; and war postponed for many years the necessity of accelerating a promotion which had ceased to be stagnant. The dullness which followed 1815 was relieved periodically by augmentations to the Regiment in the form of other battalions; but the relief was only temporary, and a darker shadow than ever loomed on the Regimental horizon, when Mr. Cardwell took office. His remedy was complex; but included, in a marked manner, the idea, born in 1782, of reducing the number of officers in subordinate positions, and increasing the proportion of field officers.

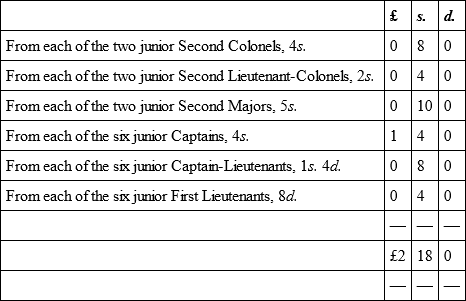

By a Royal Warrant, dated 31st October, 1782, His Majesty was pleased on the recommendation of the Board of Ordnance to declare that "the present establishment of our Royal Regiment of Artillery is in respect to promotion extremely disadvantageous to the officers belonging thereto, and that the small number of field officers does not bear a due proportion to that of officers of inferior rank." With a view to "giving encouragement suitable to the utility of the said corps, and to the merits of the officers who compose it," His Majesty decided that on the 30th of the following month the existing establishment should cease, and another be substituted, of which the two prominent features were – as will be seen by the annexed tables – a very considerable increase in the number of field officers, and the reduction of one second lieutenant in each company. It was also decided that the second lieutenants remaining over and above the number fixed for the new establishment should be borne as supernumeraries until absorbed, and that stoppages should be made in the following manner to meet the expenses of their pay, viz.: —

The annual total of this stoppage – amounting to 1058l. 10s.– was in the first instance applied to the payment of the supernumerary second lieutenants, and any surplus that might remain was ordered to be divided annually on the 31st December (in proportion to their pay) among the several officers who were at the time contributing towards it; and it was directed that as soon as the number of second lieutenants should be reduced to one per company, the stoppages should cease to be made.

The effect of the alteration in the proportion of officers in the various ranks is very distinctly shown by Colonel Miller in his pamphlet. Previous to the change, the proportion of company to field officers had been as 21 to 1; now it became as 8½ to 1.

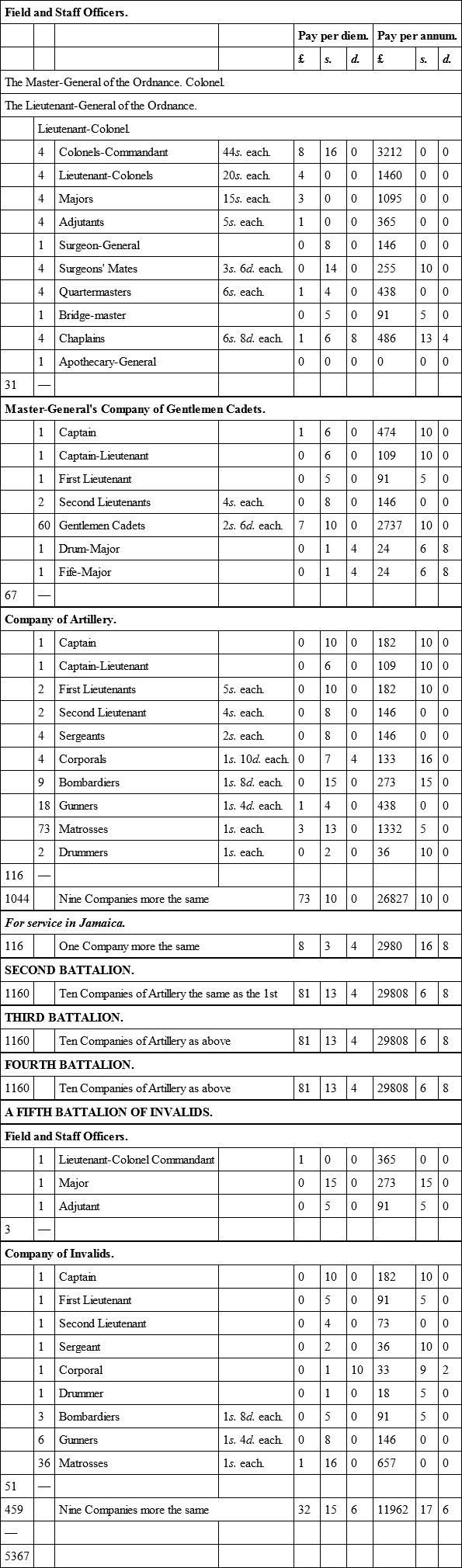

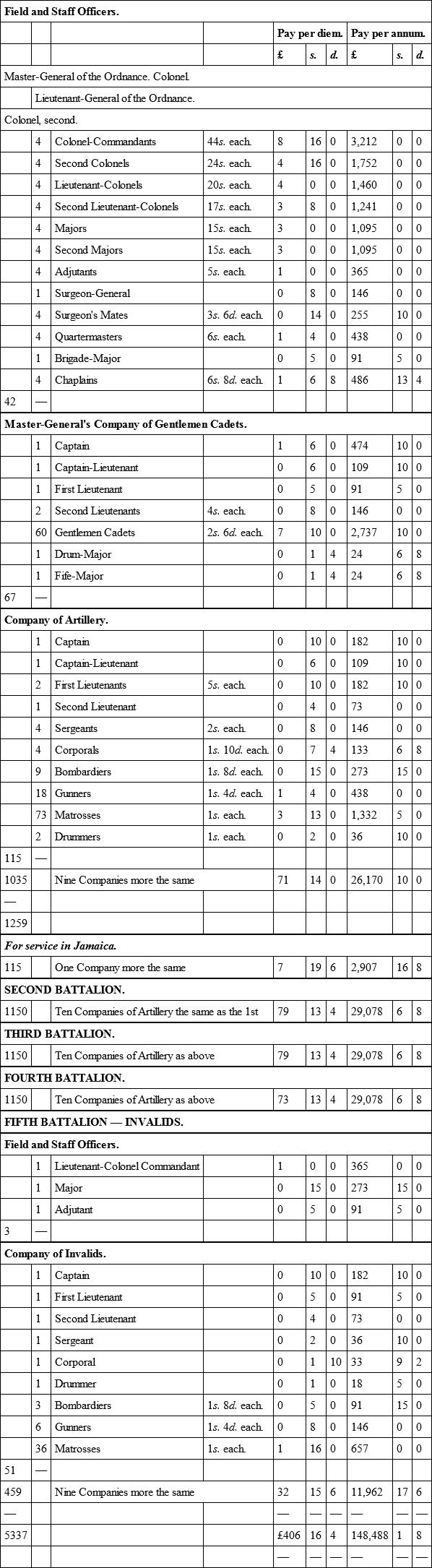

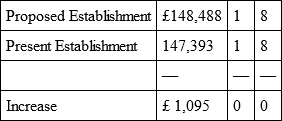

The following tables show (1) the establishment and cost of the Regiment in 1782 prior to the introduction of the new system; and (2) the proposed establishment, which came into force on the 30th November, 1782. The number of company officers – five per company – then fixed, remains, to this day, unchanged in the Horse and Field Artillery; but a subaltern per company or battery in the Garrison Artillery was reduced by the late Secretary of State for War, thus further improving the proportions of the field and company officers: —

1782. – Present Establishment of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.

1782 – Proposed Establishment of the Royal Regiment of Artillery.

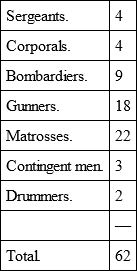

With the Peace of 1783 came a reduction in the Regiment from 5337 of all ranks to 3302, with a saving to the country of the difference between 148,488l. 1s. 8d., the cost of the old establishment, and 110,570l. 13s. 4d., the cost of the new. But the reduction and the saving were not effected at once. Every allowance was made for existing claims and interests; and for the first year after the Peace of Versailles, a charge was allowed of 129,373l. 11s. Two schemes were submitted by the Board for carrying out the required reductions: one left the number of non-commissioned officers untouched; the other reduced it by one-half and spared the privates, who now were to receive the title of gunner universally, that of matross being abolished. The first scheme was approved, but only as a temporary measure, and many of the details were left optional to the captains of companies. In the words of the Royal warrant, "If in any company the commanding officer and captain should choose to keep all the four sergeants, the four corporals, the nine bombardiers, and the eighteen gunners, he will of course have but twenty-two matrosses to retain, and must discharge the remainder, as each company is to consist only of sixty men, whether non-commissioned officers or privates (including three contingent men), besides the two drummers, so that a company wishing to preserve its present sergeants, corporals, bombardiers, and gunners, will be composed of as follows, viz.: —

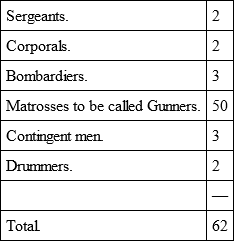

"But a company choosing to discharge any of their present sergeants, corporals, bombardiers, or gunners, will have so many more matrosses to keep, and all future vacancies of sergeants, corporals, bombardiers, or gunners will be supplied by matrosses only, until the establishment is brought to

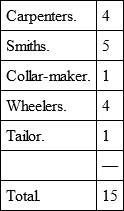

"It is further intended that fifteen men of each company should be artificers in the following proportion, viz.: —

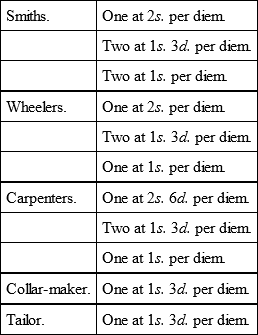

"The captains are therefore to endeavour to preserve in each company as many men of those trades as will make up the number required; and should there be in any of the companies more of one trade than the complement, they will be set down as men to be transferred to some other company that may be in want of them. These fifteen artificers, with ten labourers from each company, are to be employed as such at Woolwich, and at the different outposts or garrisons where they may be stationed, and will receive the following extra pay, viz.: —

and the labourers at 9d., for so many days as they work, which will be four in each week, the other two days being reserved for their being trained as Artillerymen. The other twenty-five men per company are to do all the duty of the Regiment.

"Such men as are entitled to go to the Invalids are to receive the pension, and whom the officers may wish to have discharged will, of course, receive that provision.

"If any of the sergeants, corporals, bombardiers, or gunners, who from their services are not entitled to the Invalids or pension, should wish to be discharged, and can take care of themselves, they should be parted with in preference to matrosses, as the difference of their pay will be a saving to Government, and the establishment will approach so much the nearer to what it is intended to be. It is not, however, meant that men under this description, whom the officers may wish to keep should be discharged, but only such as they can spare without prejudice to their companies…

(Signed) "Richmond."

All honour to the Duke of Richmond! No Master-General ever penned a more considerate and kindly Warrant, and none ever more fully realized the speciality of the Artillery service. "Without prejudice to their companies: " here is the true Artillery unit officially recognized. No word of battalions: these were mere paper organizations, devoid of all tactical meaning. History in the end always preaches truth; and at the close of a seven years' season of very earnest war, the uppermost thought in the mind of his Grace – the Colonel ex officio of the Royal Artillery – was the welfare of the companies.

The pruning-knife had to be used, for the taxpayers of England were yet staggering and reeling under the burden of wide-spread and continuous hostilities; but it was to be used with all tenderness for the susceptibilities of the true Artillery unit, and of the captains through whom the needs of that unit found expression.

The reductions having been decided upon, the following was the first distribution of the Regiment after the Peace of Versailles: —

First Battalion. – Six companies were ordered to Gibraltar to relieve the five belonging to the Second Battalion, which had been stationed there during the Siege. Four companies went to the West Indies, and one was reduced.

Second Battalion. – The whole ten companies of this battalion were ordered to Woolwich.

Third Battalion. – The companies were directed to be stationed as follows: five at Woolwich; one at the Tower; two at Portsmouth; one at Plymouth; and one at Chatham.

Fourth Battalion. – Three companies of this battalion were stationed in Jamaica, four in Canada, two at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and one in Newfoundland.

Besides various small detachments in Great Britain, the Invalid Battalion had to find the Artillery part of the garrisons of Jersey, Guernsey, Newcastle, and Scotland. It will be observed that Ireland is not mentioned, that country being garrisoned by the Royal Irish Artillery, which still enjoyed a separate existence.

On a November night in 1783, a large gathering of Artillery officers took place at the 'Bull' Inn, on Shooter's Hill, to welcome Colonel Williams and the officers who had served during the Great Siege of Gibraltar, on their return to England. Among those present were officers who had served in the Regiment during the Seven Years' War, in the American War of Independence, in the East and West Indies, and in Minorca, besides those guests whose deeds had attracted such universal admiration. This convivial meeting seems a fit standpoint from which to look back on the years of the Regiment's life and growth between 1716 and 1783. From the two companies with which it commenced, it had now attained forty service, and ten invalid companies; and instead of pleading – as was done in its infancy – inability to find men for the foreign establishments, it was able now to furnish Artillery for Canada, Gibraltar, and the West Indies, to the extent of twenty companies, besides finding drafts for the service of the East India Company, one of which had left only a few nights before this gathering to welcome the Gibraltar heroes.