полная версия

полная версияPrivate Letters of Edward Gibbon (1753-1794) Volume 2 (of 2)

Next Wednesday I conclude my forty-fifth year, and in spite of the changes of Kings and Ministers, I am very glad that I was born.

439.

To his Stepmother

Bentinck Street, May 29th, 1782.Dear Madam,

From the very strong expressions of anxious expectationand frequent disappointments, I must think that I am much more guilty than I conceived myself to be on account of my silence. Your apparent indulgence had taught me to believe that you were accustomed to my faults, that you kindly forgave them, and that without the aid of the pen or the post your own heart would inform you of the sentiments of mine. Since my last letter nothing has happened, indeed nothing can happen to affect my situation: in the midst of a plague (such is the present influenza) my health and spirits are perfectly good, and in that tranquil state Saturdays and Mondays pass away without waking me from my gentle slumber. Even my curiosity is not excited, as I have frequent opportunities of hearing circumstantial and impartial accounts of the only object that interests me at Bath.

You ask with some anxiety when you may hope to see me. I know not what to say. Though I always foresee and recollect with heartfelt satisfaction the time which I spend at the Belvidere, yet the convenient season of my visit seems to retire before me. Public events have immoderately protracted the present session of Parliament; it will certainly continue the whole of June and a considerable part of July, and as it was my intention to attend it to the last, I began to think that you would excuse me if I delayed my journey (which would suit me far better) till the beginning of Autumn. But if you have any particular reasons that make you wish to see me sooner, say it in ten lines, and I will set off in ten days. I rejoyce in every subject of your joy both private and public, and I am better pleased to hear that you are free from pain than that Rodney has destroyed a French fleet.14 Alas! had he done it two months sooner our poor administration would have stood. Every person of every party is provoked with our new Governors for taking the truncheon from the hand of a victorious Admiral, in whose place they have sent a Commander without experience or abilities.15 To-morrow they will be exposed to a small fire in the H. of C. on that popular topic. Adieu, Dear Madam, in this sickly season all my acquaintance (masters, mistresses and servants) are laid up except young Mrs. Porten and myself.

I amMost truly yours,E. G.440.

To his Stepmother

July 3rd, 1782.Dear Madam,

DEATH OF LORD ROCKINGHAM.

*I hope you have not had a moment's uneasiness about the delay of my Midsummer letter. Whatever may happen, you may rest fully secure, that the materials of it shall always be found. But on this occasion I have missed four or five posts; postponing, as usual, from morning to the evening bell, which now rings, till it has occurred to me, that it might not be amiss to inclose the two essential lines, if I only added that the Influenza has been known to me only by the report of others. Lord Rockingham16 is at last dead; a good man, though a feeble minister: his successor is not yet named, and divisions in the Cabinet are suspected. If Lord Shelburne should be the Man, as I think he will, the friends of his predecessor will quarrel with him before Christmas. At all events, I foresee much tumult and strong opposition, from which I should be very glad to extricate myself, by quitting the H. of C. with honour and without loss. Whatever you may hear, I believe there is not the least intention of dissolving Parliament, which would indeed be a rash and dangerous measure.

I hope you like Mr. Hayley's poem;17 he rises with his subject, and since Pope's death, I am satisfied that England has not seen so happy a mixture of strong sense and flowing numbers. Are you not delighted with his address to his mother? I understand that She was, in plain prose, every thing that he speaks her in verse. This summer I shall stay in town, and work at my trade, till I make some Holydays for my Bath excursion. Lady S. is at Brighton, and he lives under tents, like the wild Arabs; so that my Country house is shut up. Kitty Porten is gone on a fortnight's frolick to lodge at Windsor.

I am, Dear Madam,Ever yours.441.

To Lord Sheffield, at Coxheath Camp

Saturday night, Bentinck Street, 1782.*I sympathise with your fatigues; yet Alexander, Hannibal, &c. have suffered hardships almost equal to yours. At such a moment it is disagreeable (besides laziness) to write, because every hour teems with a new lye. As yet, however, only Charles18 has formally resigned; but Lord John, Burke, Keppel, Lord Althorpe, &c. certainly follow; your Commander-in-chief stays, and they are furious against the Duke of Richmond.*19 Why will he not go out with Fox? said somebody; because, replies a friend, he does not like to go out with any man. *In short, three months of prosperity has dissolved a Phalanx, which had stood ten years' adversity. Next Tuesday, Fox will give his reasons, and possibly be encountered by Pitt, the new Secretary, or Chancellor, at three and twenty. The day will be rare and curious, and, if I were a light Dragoon, I would take a gallop on purpose to Westminster. Adieu. I hear the bell. How could I write before I knew where you dwelt?*

E. G.442.

To Lord Sheffield

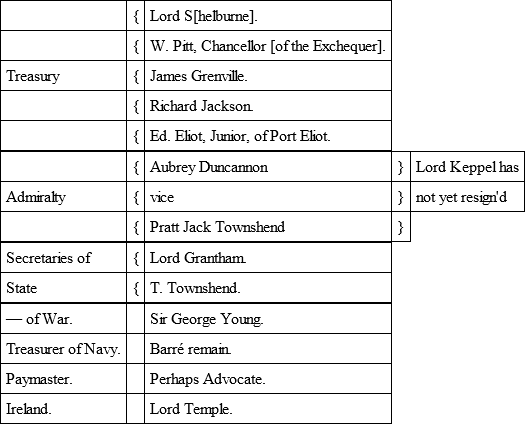

July 10th, 1782.LORD SHELBURNE'S MINISTRY.

Authentic List. 20

Yesterday was a rare day.

Vera Cop,E. G.443.

To Lord Sheffield

July 23rd, 1782.The papers say you are at Coxheath. Write. Bad news from India; I am afraid that we have lost a ship and that Hyder has won a battle.21 None, therefore good, from Lord Howe since every day fortifies him.22 Within this last fortnight prodigious exertions by the Admiralty, till then they were fast asleep. The Advocate arrived last night, but has not yet accepted. To-morrow I visit Eden at his farm near Bromley. If you and my Lady could give me a meeting in a house, I would run down even for three or four days: but I do not admire canvass. Adieu.

E. G.Aunt Hester seems to want some intelligence.

444.

To his Stepmother

August 10th, 1782.Dear Madam,

A person whom you would scarcely suspect, General Conway as commander in Chief, is the real author of my silence, which as usual has insensibly lasted far beyond my first intentions. Lord Sheffield is a slave, his master's resolutions are obscure and fluctuating, and I have waited from post to post till he could mark some week for our meeting in Sussex, which might leave the rest of my time at liberty for my Bath expedition. Though I can obtain no satisfaction from him, I must not suffer another Monday to slide away without saying that I am alive, well, and unless the Arab should seize (he has no choice) that particular moment, in full expectation of gratifying my wishes by a visit to Bath about the 20th of next month. I flatter myself that I shall find you not affected by the long winter which we still feel, though a friend of mine, an Astronomer, assured me that yesterday was the last of the dog days.

It is impossible to know what to say of our public affairs, and the most knowing are only such by the knowledge of their ignorance. The next session of Parliament will be the warmest and most irregular battle that has ever been fought in that place, and each man (except some leaders) is at the moment uncertain of the party which inclination, opinion, or connection will prompt him to embrace. You see that Mr. Eliot, or at least his family, are become courtiers; his son (a very unmeaning youth) is a Lord of the Treasury, an office which was formerly the reward of twenty years' able and faithful service. The Minister has not lost, for he never possessed, the public confidence, and Lord N[orth], if he chuses to act, has the balance of the country in his hands. A propos of the Eliots they are still in town. We meet seldom, but with the utmost propriety and equal regard.

IMMERSED IN THE ROMAN EMPIRE.

My private life is a gentle and not unpleasing continuation of my old labours, and I am again involved, as I shall be for some years, in the decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Some fame, some profit, and the assurance of daily amusement encourage me to persist. I am glad you are pleased with Mr. Hayley's poem; perhaps he might have been less diffuse, but his sense is fine and his verse is harmonious. – Mrs. Porten is just returned from a six weeks' excursion in lodgings at Windsor, which she enjoyed (the Terrace, the Air, and the Royal family) with all the spirit of youth. Her elder brother is quiet in his new employment and apartments in Kensington palace. I envy him the latter, and had there been no Revolution I might have obtained a similar advantage. At present I am on the ground, but the weather may change, and compared with recent darkness, the clouds are beginning to break away.

I am, Dear Madam,Ever yours,E. G.445.

To his Stepmother

Bentinck Street, Sept. 14, 1782.Dear Madam,

As you suffered by the long winter, I may reasonably, as I warmly, hope that your health and spirits have been permanently restored by the milder Spring or Autumn which this month has introduced: – For many reasons you will be surprised, though I think pleased, to hear that I have fixed myself for this season in a country villa of Hampton court. My friend Mr. Hamilton (I must distinguish him by the impertinent epithet of 'single speech') has very obligingly lent me a ready furnished house close to the Palace, and opening by a private door into the Royal garden, which is maintained for my use but not at my expence. The air and exercise, good roads and neighbourhood, the opportunity of being in London at any time in two hours, and the temperate mixture of society and study, adapt this new scene very much to my wishes, and must entirely remove your kind apprehensions of my injuring my health (which I have never done) by excessive labour. I find or make many acquaintance, and among others I have visited your old friend Mrs. Manhood (Ashby) at Isleworth in her pleasant summer-house on the Thames. She overwhelms me with civility, but you need not indulge either hopes or fears: as I hear she is going to accept Sir William Draper23 for her third husband.

You will naturally suppose, and will not I think be displeased that I should enjoy this new and unexpected situation as long as the fine weather continues, and our past hardships encourage us to depend on the favour, at least the first favours of the month of October. Beyond that period the prospect in every sense of the word is cloudy, and my future motions will be partly regulated by parliament, and the intanglement of some private pursuits with public affairs. I still flatter myself with the hope of securing two or three weeks for Bath; but if I should again delay that visit till Christmas, I shall prove my perfect confidence in your indulgent friendship, and in your firm belief of my tender attachment, which can alone justify such freedom of conduct. Of the Sheffields I know little, seldom hear from, and am totally ignorant when I shall see them. The Eliots are gone into Cornwall. They say that the son is going to marry Lady Sarah Pitt,24 sister to his intimate friend the Chancellor of the Exchequer.

From the little I have read I agree with you about Gilbert Stuart's25 book, but I cannot forgive your indifference and almost aversion to one of the most amiable men, and masterly compositions in the world.

I am, Dear Madam,Most truly yours,E. G.I lay in town last night, and am just setting out for Hampton Court.

N.B. – I never travel after dark, but our dangers are almost over.

446.

To Lord Sheffield

September 29th, 1782.HIS HAMPTON COURT VILLA.

I should like sometimes to hear whether you survive the scenes of action and danger in which a Dragoon is continually involved. What a difference between the life of a Dragoon and that of a Philosopher! and I will freely own that I (the Philosopher) am much better satisfied with my own independent and tranquil situation, in which I have always something to do, without ever being obliged to do any thing. The Hampton Court Villa has answered my expectation, and proved no small addition to my comforts; so that I am resolved next summer to hire, borrow, or steal, either the same, or something of the same kind. Every morning I walk a mile or more before breakfast, read and write quantum sufficit, mount my chaise and visit in the neighbourhood, accept some invitations, and escape others, use the Lucans as my daily bread, dine pleasantly at home or sociably abroad, reserve for study an hour or two in the evening, lye in town regularly once a week, &c. &c. &c. I have anounced to Mrs. G. my new Arrangements; the certainty that October will be fine, and my encreasing doubts whether I shall be able to reach Bath before Christmas. Do you intend (but how can you intend any thing?) to pass the winter under Canvas? Perhaps under the veil of Hampton Court I may lurk ten days or a fortnight at Sheffield, if the enraged Lady or cat does not shut the doors against me.

The Warden26 passed through in his way to Dover. He is not so fat, and more chearful than ever. I had not any private conversation with him; but he clearly holds the balance; unless he falls asleep and lets it fall from his hand. The Pandæmonium (as I understand) does not meet till the 26th of November. I feel with you that a nich is grown of higher value, but think that only an additional argument for disposing of it. And so by this time Lord L.27 is actually turned off. Do you know his partner (Miss Courtenay, the Lord's sister), about thirty, only £4000, not handsome, but very pleasant. I am at a loss where to address my condoleance, I would say congratulation. Town is more a desert than I ever knew it. I arrived yesterday, dined at Sir Joshua's with a tolerable party; the chaise is now at the door; I dine at Richmond, lye at Hampton, &c. Adieu.

E. G.447.

To his Stepmother

Hampton Court, October 1st, 1782.My dear Madam,

I feel your anxiety, and am impatient to assure you that the report of your officious visitor is absolutely without foundation. I had not any complaints when I came down to this place; but the air, exercise and dissipation have given me fresh spirits; and I should be apt to fix on the last month as the part of my life in which I have enjoyed the most perfect health. You may depend on my word of honour, that in case of any real alarm, you shall hear from myself or from Caplen. – Excuse brevity, as I save a day, perhaps more, by sending Caplen with Duplicates to London, one copy for the post, the other to take the chance of greater dispatch by the coach. I wish to know what you think of me and my schemes; if you are not perfectly satisfied with my confidence, you may be somewhat displeased with my seeming neglect. I fear we shall not meet till Christmas.

I amEver yours,E. Gibbon.448.

To Lord Sheffield at Coxheath Camp

Bentinck Street, October 14th, 1782.RELIEF OF GIBRALTAR.

*On the approach of winter, my paper house of Hampton becomes less comfortable; my visits to Bentinck Street grow longer and more frequent, and the end of next week will restore me to the town, with a lively wish, however, to repeat the same, or a similar experiment, next Summer. I admire the assurance with which you propose a month's residence at Sheffield, when you are not sure of being allowed three days. Here it is currently reported, that Camps will not separate till Lord Howe's return from Gibraltar,28 and as yet we have no news of his arrival. Perhaps, indeed, you have more intimate correspondence with your old school-fellow, Lord Shelburne, and already know the hour of your deliverance. I should like to be informed. As Lady S. has entirely forgot me, I shall have the pleasure of forming a new acquaintance. I have often thought of writing, but it is now too late to repent.

I am at a loss what to say or think about our Parliamentary state. A certain late Secretary of Ireland,29 the husband of Polly Jones, reckons the House of Commons thus: Minister 140, Reynard 90, Boreas 120, the rest unknown, or uncertain. The last of the three, by self or agents, talks too much of absence, neutrality, moderation. I still think he will discard the game.

I am not in such a fury with the letter of American independence;30 but it seems ill-timed and useless; and I am much entertained with the Metaphysical disputes between Government and secession about the meaning of it. Lord Lough[borough] will be in town Sunday sen-night. I long to see him and Co. I think he will take a very decided part. If he could throw aside his Gown, he would make a noble Leader. The East India news are excellent; the French gone to the Mauritius, Heyder desirous of peace, the Nizam and Mahrattas our friends, and 70 Lack of Rupees in the Bengal treasury, while we were voting the recall of Hastings.31 Adieu. Write soon.

E. G.449.

To Lady Sheffield

Bentinck Street, October 31st, 1782.Although I am provoked (it is always right to begin first) with your long and unaccountable silence, yet I cannot help wishing (a foolish weakness) to learn whether you and the two infants are still alive, and what have been the summer amusements of your widowed and their orphan state. Some indirect intelligence inclines me to suspect that the Baron himself has quitted before this time a house of Canvas for one of brick, and that he enjoys a short interval between the fatigues of War and those of Government. Should he happen to find himself in your neighbourhood you may inform him that Hugonin (good creature) came to town purposely on my business and passed three hours with me this morning. Harris has resigned his Case of the conflagration, and either by a sale to Lord Stawell or by a new Tenant we shall make it rather a profitable affair.

ENTHUSIASM FOR SIR GEORGE ELIOTT.

You have doubtless received very accurate accounts of my proceedings from the Cambridges by which channel I have likewise obtained very frequent narratives of your life and conversation, and this mutual Gazette has contributed not a little to stifle the reproaches of my conscience. In my excursions round the Hampton neighbourhood, I have often visited and dined with them, and found him properly sensible of his happyness in the absence of his wife: indeed I never saw a man more improved by any fortunate event. My campaign, and it has been a pleasant one, is now closed, but in the time which remains before the opening of our Pandemonium, I should not dislike to breathe for a week or ten days the air of Sheffield Place, and as the Lord will be accessible in town before Christmas, my attack (according to modern rules) will be chiefly designed for the Lady. About Wednesday or Thursday next would be the day that I should think of moving, but I wish to be informed how far such a plan may consist (as the Scotch say) with other arrangements. Adieu. Is not Elliot32 a glorious old fellow? We suspend our judgment of Lord Howe, yet I like the prospect.

I embrace, &c.,E. G.450.

To his Stepmother

November 7th, 1782.Dear Madam,

Last week I finished my Hampton Court expedition, and think myself obliged to the person and to the accident which have thrown that unexpected but not unpleasing variety into my Summer life. I am now fixed in town till Christmas, or if Lord Sheffield who has quitted his camp should drag me into Sussex, it can be only for three or four days.

The Parliamentary campaign is approaching very fast,33 and a very singular one it must be from the conflict of three parties, each of which will be exposed in its turn to the direct or oblique attacks of the other two. As a matter of curiosity I shall derive some gratification from my silent seat, but at present I do not perceive its use in any other light. From honour, gratitude and principle I am and shall be attached to Lord N., who will lead a very respectable force into the field, but I much doubt whether matters are ripe for either conquest or coalition, and the havock which Burke's bill has made of places, &c., encreases the difficulties of a new arrangement. However a month or two may change the face of things, and the faces of men.

WILLIAM PITT AND MRS. SIDDONS.

Among those men surely Will Pitt the second is the most extraordinary.34 I know you never liked the father, and I have no connection public or private with the son. Yet we cannot refuse to admire a youth of four and twenty whom eloquence and real merit have already made Chancellor of the Exchequer without his promotion occasioning either surprize or censure.

We are much indebted to your Bath Theatre for Mrs. Siddons:35 two years ago, and in the part of Lady Townley, she did not strike me: but I saw her last night with the most exquisite pleasure. She gave sense and spirit to a wretched play (the Fatal Marriage), and displayed every power of voice, action, and countenance to a degree which left me nothing to wish. To-morrow I promise myself still more satisfaction from Jane Shore, as the character is more worthy of her talents. Adieu, Dear Madam. Inform me that the beginning of the winter has not affected your health. Whatever may be the state of my namesake, I hope at Christmas to bring you a sound body, and a mind not dissatisfied with external things, because it is not dissatisfied with itself.

I amEver yours,E. G.451.

To his Stepmother

December 21st, 1782.Dear Madam,

I write a little letter on little paper because I shall soon have the pleasure of conversing with you in a less laborious manner. Next Thursday I propose to begin my journey for Bath, but as the times (in a public and private light) are very hard, I shall travel with my own horses, lye two nights on the road, and reach the Belvidere for a late dinner Saturday. You will be so good as to secure me a lodging; the nearness to your house will be its best recommendation, as you are my sole inducement. If any business should detain me two or three days longer in town, you may depend on the earliest notice.

I am, Dear Madam,Ever yours,E. G.452.

To his Stepmother

Bentinck Street, December 26th, 1782.Dear Madam,

It was not in my power to set out this morning (Thursday), and therefore I cannot hope to reach Bath Saturday. I am not perfectly sure whether Sunday or Monday will be the day of my arrival: for which reason I shall eat a mutton chop at the Devizes, and beg you would not wait dinner for me.

I amMost truly yours,E. G.453.

To Lord Sheffield

Tuesday evening, 1782.THE DEARTH OF NEWS.

*I have designed writing every post. – The air of London is admirable; my complaints have vanished, and the Gout still respects me. Lord L., with whom I passed an entire day, is very well satisfied with his Irish expedition, and found the barbarous people very kind to him: the castle is strong, but the volunteers are formidable. London is dead, and all intelligence so totally extinct, that the loss of an army would be a favourable incident. We have not even the advantage of Shipwrecks, which must soon, with the society of Ham[ilton] and Lady Shelley, become the only pleasures of Brighton. My lady is precious, and deserves to shine in London, when she regains her palace. The workmen are slow, but I hear that the Minister talks of hiring another house after Christmas. Adieu, till Monday seven-night.* Shall Caplin get you a lodging?

454.

To his Stepmother

Bentinck Street, Jan. 16th, 1783.Dear Madam,

I reached London after an easy and pleasant journey, and am now seated in my library before a good fire, and among three or four thousand of my old acquaintance. The prospect of my future life is not gloomy: yet I should esteem myself a very happy man indeed, if every fortnight could be of as pure a white as the last which I have spent at Bath in the society of the most sincere as well as amiable of my friends.