полная версия

полная версияThe Campaign of Trenton 1776-77

That force lay quietly at Morristown until the 12th of the month, when it was again put in motion toward Vealtown, now Bernardsville.

Gates arrives.

Lee taken.

At this time a second detachment from the army of the North, under Gates,[3] was on the march across Sussex County to the Delaware. Being cut off from communication with the commander-in-chief, Gates sent forward a staff officer to learn the condition of affairs, report his own speedy appearance, and receive directions as to what route he should take, Hearing that Lee was at Morristown, this officer pushed on in search of him, and at four o'clock in the morning of the 13th, he found Lee quartered in an out-of-the-way country tavern at Baskingridge, three miles from his camp, and by just so much nearer the enemy, whose patrols, since Washington had been disposed of, were now scouring the roads in every direction. One of these detachments surprised the house Lee was in, and before noon the crestfallen general was being hurried off a prisoner to Brunswick by a squadron of British light-horse.

Lee's troops, now Sullivan's, with those of Gates, one or two marches in the rear, freed from the crafty hand that had been leading them astray, now pressed on for the Delaware, and thus that concert of action, for which Washington had all along labored in vain, was again restored between the fragments of his army, impotent when divided, but yet formidable as a whole.

Lee's written and spoken words, if indeed his acts did not speak even louder, leave no doubt as to his purpose in amusing Washington by a show of coming to his aid, when, in fact, he had no intention of doing so. He not only assumed the singular attitude, in a subordinate, of passing judgment upon the propriety or necessity of his orders, – orders given with full knowledge of the situation, – but proceeded to thwart them in a manner savoring of contempt. Lee was Washington's Bernadotte. Neither urging, remonstrance, nor entreaty could swerve him one iota from the course he had mapped out for himself. Conceiving that he held the key to the very unpromising situation in his own hands, he had determined to make the gambler's last throw, and had lost.

Although Lee's conduct toward Washington cannot be justified, it is more than probable that some such success as that which Stark afterwards achieved at Bennington, under conditions somewhat similar, though essentially different as to motives, might, and probably would, have justified Lee's conduct to the nation, and perhaps even have raised him to the position he coveted – of the head of the army, on the ruins of Washington's military reputation. Could he even have cut the enemy's line so as to throw it into confusion, his conduct might have escaped censure. With this end in view he designed holding a position on the enemy's flank,[4] arguing, perhaps, that Washington would be compelled to reënforce him rather than see him defeated, with the troops now beyond the Delaware. Washington saw through Lee's schemes, refused to be driven into doing what his judgment did not approve, and the tension between the two generals was suddenly snapped by the imprudence or worse of Lee himself.

Captain Harris,[5] who saw Lee brought to Brunswick a prisoner, has this to say of him: "He was taken by a party of ours under Colonel Harcourt, who surrounded the house in which this arch-traitor was residing. Lee behaved as cowardly in this transaction as he had dishonorably in every other. After firing one or two shots from the house, he came out and entreated our troops to spare his life. Had he behaved with proper spirit I should have pitied him. I could hardly refrain from tears when I first saw him, and thought of the miserable fate in which his obstinacy has involved him. He says he has been mistaken in three things: first, that the New England men would fight; second, that America was unanimous; and third, that she could afford two men for our one."[6]

VIII

THE OUTLOOK

To all intents the campaign of 1776 had now drawn its lengthened disasters to a close. It had indeed been protracted nearly to the point of ruin, with the one result, that Philadelphia was apparently safe for the present. But with Washington thrown back across the Delaware, Lee a prisoner, Congress fled to Baltimore, Canada lost, New York lost, the Jerseys overrun, the royal army stretched out from the Hudson to the Delaware and practically intact, while the patriot army, dwindled to a few thousands, was expected to disappear in a few short weeks, the situation had grown desperate indeed.

So hopeless indeed was the outlook everywhere that the ominous cry of "Every one for himself" – that last despairing cry of the vanquished – began to be echoed throughout the colonies. We have seen that even Washington himself seriously thought of retreating behind the Alleghanies, which was virtual surrender. Even he, if report be true, began to think of the halter, and Franklin's little witticism, on signing the Declaration, of, "Come, gentlemen, we must all hang together or we shall hang separately," was getting uncomfortably like inspired prophecy.

If we turn now to the people, we shall find the same apparent consenting to the inevitable, the same tendency of all intelligent discussion toward the one result. One instance only of this feeling may be cited here, as showing how the young men – always the least despondent portion of any community – received the news of the retreat through the Jerseys.

Elkanah Watson sets down the following at Plymouth, Mass.: "We looked upon the contest as near its close, and considered ourselves a vanquished people. The young men present determined to emigrate, and seek some spot where liberty dwelt, and where the arm of British tyranny could not reach us. Major Thomas (who had brought them the dispiriting news from the army) animated our desponding spirits with the assurance that Washington was not dismayed, but evinced the same serenity and confidence as ever. Upon him rested all our hopes."

British plans.

At the British headquarters the contest, with good reason, was felt to be practically over. Unless all signs failed one short campaign would, beyond all question, end it; for at no point were the Americans able to show a respectable force. In the North a fresh army, under General Burgoyne, was getting ready to break through Ticonderoga and come down the Hudson with a rush, carrying all before them, as Cornwallis had done in the Jerseys. This would cut the rebellion in two. On the same day that Washington crossed the Delaware, Clinton had seized Newport, without firing a shot. This would hold New England in check. In short, should Howe's plans for the coming season work, as there was every reason to expect, then there would be little enough left of the Revolution in its cradle and stronghold, with the troops at New York, Albany, and Newport acting in well-devised combination.

Brilliant only when roused by the presence of danger, Howe as easily fell into his habitual indolence when the danger had passed by. In effect, what had he to fear? Washington was beyond the Delaware, with the débris of the army he had lately commanded, which served him rather as an escort than a defence. If let alone, even this would shortly disappear.

Under these circumstances Howe felt that he could well afford to give himself and his troops a breathing-spell. This was now being put in train. Cornwallis was about to sail for England, on leave of absence. The garrison of New York disposed itself to pass the winter in idleness, and even those detachments doing outpost duty in the Jerseys, after having chased Washington until they were tired, turned their attention exclusively to the disaffected inhabitants. The field had already been reaped, and these troops were the gleaners.

Chain of posts.

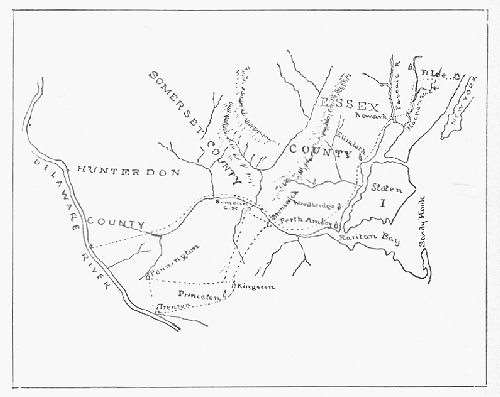

To hold what had been gained a chain of posts was now stretched across the Jerseys from Perth Amboy to the Delaware, with Trenton, Bordentown, and Burlington as the outposts and New Brunswick as the dépôt, the first being well placed either for making an advance, or for checking any attempts by the Americans to recross the river. Washington believed that the British would be in Philadelphia just as soon as the ice was strong enough to bear artillery. If the expected dissolution of his army had happened, no doubt the enemy's advanced troops would have taken possession of the city at once. And it is even quite probable that this contingency was considered a foregone conclusion, since British agents were now actively at work in Washington's own camp, undermining the feeble authority which everybody believed was tottering to its fall. Be that as it may, the fact remains that active operations were for the present wholly suspended. At the officers' messes or in the barracks all the talk was of going home. Besides, if Howe had really wanted to take Philadelphia there was nothing to prevent his doing so. There were no defences. If saved at all, the city must be defended in the field, not in the streets.

Bordentown being rather the most exposed, Count Donop was left there with some 2,000 Hessians, and Colonel Rall at Trenton with 1,200 to 1,300 more. Both were veterans. As these Hessians were about equally hated and feared, it was well reasoned that they would be all the more watchful against a surprise.

THE ATTACK ON TRENTON.

Rall and Donop.

As soon as he had time to look about him, Donop at once extended his outposts down to Burlington, on the river, and to Black Horse, on the back-road leading south to Mt. Holly, thus establishing himself at the base point of a triangle from which his outposts could be speedily reënforced, either from Bordentown or each other. The post at Burlington was only eighteen miles from Philadelphia.

In order to understand the efforts subsequently made to break through it this line should be carefully traced out on the map. In spots it was weak, yet the long gaps, like that between Princeton and Trenton, and between Princeton and Brunswick, were thought sufficiently secured by occasional patrols.

To meet these dispositions of the enemy Washington stretched out the remnant of his force along the opposite bank of the Delaware, from above Trenton to below Bordentown, looking chiefly to the usual crossing places, which were being vigilantly watched.

OPERATIONS IN THE JERSEYS.

Under date of December 16 a British officer writes home as follows: "Winter quarters are now fixed. Our army forms a chain of about ninety miles in length from Fort Lee, where our baggage crossed, to Trenton on the Delaware, which river, I believe, we shall not cross till next campaign, as General Howe is returning to New York. I understand we are to winter at a small village near the Raritan River, and are to form a sort of advanced picket. There is mountainous ground very near this post where the rebels are still in arms, and are expected to be troublesome during the winter."

Cruelties of troops.

He then goes on to speak of the deplorable condition in which the inhabitants had been left by the rival armies, dividing the blame with impartial hand, and moralizing a little, as follows: "A civil war is a dreadful thing; what with the devastation of the rebels, and that of the English and Hessian troops, every part of the country where the scene of the action has been looks deplorable. Furniture is broken to pieces, good houses deserted and almost destroyed, others burnt; cattle, horses, and poultry carried off; and the old plundered of their all. The rebels everywhere left their sick behind, and most of them have died for want of care."

This telling piece of testimony is introduced here not only because it comes from an eye-witness, but from an enemy. Beneath the uniform the man speaks out. But his omissions are still more eloquent. It was not so much the loss of property, bad as that was, as the nameless atrocities everywhere perpetrated by the royal troops upon the young, the helpless, and the innocent, that makes the tale too revolting to be told. In truth, all that part of the Jerseys held by the enemy had been given up to indiscriminate rapine and plunder. It was in vain that the victims pleaded the king's protection. As vainly did they appeal to the humanity of the invaders. The brutal soldiery defied the one and laughed at the other. Finding that the promised pardon and mercy were synonymous with murder, arson, and rapine, such a revulsion of feeling had taken place that the authors of these cruelties were literally sleeping on a volcano; and where patriotism had so lately been invoked in vain, hope of revenge was now turning every man, woman, and child into either an open or a secret foe to the despoilers of their homes. One little breath only was wanting to fan the revolt to a flame; one little spark to fire the train. All eyes, therefore, were instinctively turned to the banks of the Delaware.

IX

THE MARCH TO TRENTON

Spirit of the officers.

Post at Bristol.

Enough has been said to show that only heroic measures could now save the American cause. Fortunately Washington was surrounded by a little knot of officers of approved fidelity, whose spirit no reverses could subdue. And though a calm retrospect of so many disasters, with all the jealousies, the defections, and the terror which had followed in their wake, might well have carried discouragement to the stoutest hearts, this little band of heroes now closed up around their careworn chief, and like the ever-famous Guard at Waterloo, were fully resolved to die rather than surrender. This was much. It was still more when Washington found his officers inspired by the same hope of striking the enemy unawares which he himself had all along secretly entertained. The hope was still further encouraged by a reënforcement of Pennsylvania militia, whose pride had been aroused at seeing the invader's vedettes in sight of their capital. These were posted at Bristol, under Cadwalader,[1] as a check to Count Donop, while what was left of the old army was guarding the crossings above, as a check to Rall.

To do something, and to do it quickly, were equally imperative, because the term of the regular troops would expire in a few days more, and no one realized better than the commander-in-chief that the militia could not long be held together inactive in camp.

Rall's danger.

The isolated situation of Rall and Donop seemed to invite attack. Their fancied security seemed also to presage success. An inexorable necessity called loudly for action before conditions so favorable should be changed by the freezing up of the Delaware when, if the enemy had any enterprise whatever, the river would no longer prevent, but assist, his marching into Philadelphia, and perhaps dictating a peace from the halls of Congress.

Donop being considerably nearer Philadelphia than Rall, was, as we have seen, being closely watched by Cadwalader, whose force being largely drawn from the city had the best reasons for wishing to be rid of so troublesome a neighbor.

Gates sulking.

More especially in view of possible contingencies, which he could not be on the ground to direct, Washington sent his able adjutant-general, Reed,[2] down to aid Cadwalader. This action, too, removed a difficulty which had arisen out of Gates' excusing himself from taking this command on the plea of ill-health.

In Philadelphia.

Below Cadwalader, again, Putnam was in command at Philadelphia, with a fluctuating force of local militia, only sufficiently numerous to furnish guards for the public property, protect the friends, and watch the enemies, of the cause, between whom the city was thought to be about equally divided. Most reluctantly the conclusion had been reached that the appearance of the British in force, on the opposite bank of the Delaware, would be the signal for a revolt. Here, then, was another rock of danger, upon which the losing cause was now steadily drifting, – another warning not to delay action.

It was then that Washington resolved on making one of those sudden movements so disconcerting to a self-confident enemy. It had been some time maturing, but could not be sooner put in execution on account of the wretched condition of Sullivan's (lately Lee's) troops, who had come off their long march, as Washington expresses it, in want of everything.

A first move.

Putnam was the first to beard the lion by throwing part of his force across the Delaware.3 Whether this was done to mask any purposed movement from above, or not, it certainly had that result. After crossing into the Jerseys Griffin marched straight to Mt. Holly, where he was halted on the 22d, waiting for the reënforcements he had asked for from Cadwalader. Donop having promptly accepted the challenge, marched against Griffin, who, having effected his purpose of drawing Donop's attention to himself, fell back beyond striking distance.

It was Washington's plan to throw Cadwalader's and Ewing's[4] forces in between Donop and Rall, while Griffin or Putnam was threatening Donop from below; and he was striking Rall from above. Had these blows fallen in quick succession there is little room to doubt that a much greater measure of success would have resulted.

Orders for the intended movement were sent out from headquarters on the 23d. They ran to this effect:

Rall the object.

Cadwalader at Bristol, Ewing at Trenton Ferry, and Washington himself at McKonkey's Ferry, were to cross the Delaware simultaneously on the night of the 25th and attack the enemy's posts in their front. Cadwalader and Ewing having spent the night in vain efforts to cross their commands, returned to their encampments. It only remains to follow the movements of the commander-in-chief, who was fortunately ignorant of these failures.

Twenty-four hundred men, with eighteen cannon, were drawn up on the bank of the river at sunset. Tolstoi claims that the real problem of the science of war "is to ascertain and formulate the value of the spirit of the men, and their willingness and eagerness to fight." This little band was all on fire to be led against the enemy. No holiday march lay before them, yet every officer and man instinctively felt that the last hope of the Republic lay in the might of his own good right arm.

Did we need any further proof of the desperate nature of these undertakings, it is found in the matchless group of officers that now gathered round the commander-in-chief to stand or fall with him. With such chiefs and such soldiers the fight was sure to be conducted with skill and energy.

Strong array of officers.

Greene, Sullivan, St. Clair, Sterling, Knox, Mercer, Stephen, Glover, Hand, Stark, Poor, and Patterson were there to lead these slender columns to victory. Among the subordinates who were treading this rugged pathway to renown were Hull, Monroe, Hamilton, and Wilkinson. Rank disappeared in the soldier. Major-generals commanded weak brigades, brigadiers, half battalions, colonels, broken companies. Some sudden inspiration must have nerved these men to face the dangers of that terrible night. History fails to show a more sublime devotion to an apparently lost cause.

The Delaware crossed.

Boats being held in readiness the troops began their memorable crossing. Its difficulties and dangers may be estimated by the failure of the two coöperating; corps to surmount them. Of this part of the work Glover[5] took charge. Again his Marblehead men manned the boats, as they had done at Long Island; and though it was necessary to force a passage by main strength through the floating ice, which the strong current and high wind steadily drove against them, the transfer from the friendly to the hostile shore slowly went on in the thickening darkness and gloom of the waiting hours.

Little by little the group on the eastern shore began to grow larger as the hours wore on. Washington was there wrapped in his cloak, and in that inscrutable silence denoting the crisis of a lifetime. Did his thoughts go back to that eventful hour when he was guiding a frail raft through the surging ice of the Monongahela? Knox was there animating the utterly cheerless scene by his loud commands to the men in charge of his precious artillery, for which the shivering troops were impatiently waiting. At three o'clock the last gun was landed. The crossing had required three hours more than had been allowed for it. Nearly another hour was used up in forming the troops for the march of nine miles to Trenton, which could hardly be reached over such a wretched road, and in such weather, in less than from three to four hours more. To make matters worse, rain, hail, and sleet began falling heavily, and freezing as it fell.

To surround and surprise Trenton before daybreak was now out of the question. Nevertheless, Washington decided to push on as rapidly as possible; and the troops having been formed in two columns, were now put in motion toward the enemy.

The march was horrible. A more severe winter's night had never been experienced even by the oldest campaigners. To keep moving was the only defence against freezing. Enveloped in whirling snow-flakes, encompassed in blackest darkness, the little column toiled steadily on through sludge ankle-deep, those in the rear judging by the quantity of snow lodged on the hats and coats of those in front, the load that they themselves were carrying. Not a word, a jest, or a snatch of song broke the silence of that fearful march.

At a cross-road four and a half miles from Trenton the word was passed along the line to halt. Here the columns divided. With one Greene filed off on a road bearing to the left, which, after making a considerable circuit, struck into Trenton more to the east. Washington rode with this division. The other column kept the road on which it had been marching. Sullivan led this division with Stark in the van. At this moment Sullivan was informed that the muskets were too wet to be depended upon. He instantly sent off an aid to Washington for further orders. The aid came galloping back with the order to "go on," delivered in a tone which he said he should never forget. With grim determination Sullivan again moved forward, and the word ran through the ranks, "We have our bayonets left."

All this time Ewing was supposed to be nearing Trenton from the south. In that case the town would be assaulted from three points at once, and a retreat to Bordentown be cut off.

X

TRENTON

Very early in the evening there had been firing at Rall's outposts, but the careless enemy hardly gave it his attention. Some lost detachment had probably fired on the pickets out of mere bravado. The night had been spent in carousal, and the storm had quieted Rall's mind as regards any danger of an attack.[1]

The attack.

But in the gray dawn of that dark December morning the two assaulting columns, emerging like phantoms from the midst of the storm, were rapidly approaching the Hessian pickets. All was quiet. The newly fallen snow deadened the rumble of the artillery. The pickets were enjoying the warmth of the houses in which they had taken post, half a mile out of town, when the alarm was raised that the enemy were upon them. They turned out only to be swept away before the eager rush of the Americans, who came pouring on after them into the town, as it seemed in all directions, shouting and firing at the flying enemy. That long night of exposure, of suspense, the fatigue of that rapid march, were forgotten in the rattle of musketry and the din of battle.

Street combats.

Roused by the uproar the bewildered Hessians ran out of their barracks and attempted to form in the streets. The hurry, fright, and confusion were said to be like to that with which the imagination conjures up the sounding of the last trump.[2] Grape and canister cleared the streets in the twinkling of an eye. The houses were then resorted to for shelter. From these the musketry soon dislodged the fugitives. Turned again into the streets the Hessians were driven headlong through the town into an open plain beyond it. Here they were formed in an instant, and Rall, brave enough in the smoke and flame of combat, even thought of forcing his way back into the town.

Sullivan in action.

But Washington was again thundering away in their front with his cannon. In person he directed their fire like a simple lieutenant of artillery. Off at the right the roll of Sullivan's musketry announced his steady advance toward the bridge leading to Bordentown. The road to Princeton was held by a regiment of riflemen. Those troops, whom Sullivan had been driving before him, saved themselves by a rapid flight across the Assanpink. Why was not Ewing there to stop them! Sullivan promptly seized the bridge in time to intercept a disorderly mass of Hessian infantry, who had broken away from the main body in a panic, hoping to make their escape that way.