полная версия

полная версияThe Campaign of Trenton 1776-77

Samuel Adams Drake

The Campaign of Trenton 1776-77

PRELUDE

Seldom, in the annals of war, has a single campaign witnessed such a remarkable series of reverses as did that which began at Boston in March, 1776, and ended at Morristown in January, 1777. Only by successive defeats did our home-made generals and our rustic soldiery learn their costly lesson that war is not a game of chance, or mere masses of men an army.

Though costly, this sort of discipline, this education, gradually led to a closer equality between the combatants, as year after year they faced and fought each other. When the lesson was well learned our generals began to win battles, and our soldiers to fight with a confidence altogether new to them. In vain do we look for any other explanation of the sudden stiffening up of the backbone of the Revolutionary army, or of the equally sudden restoration of an apparently dead and buried cause after even its most devoted followers had given up all as lost. As with expiring breath that little band of hunted fugitives, miserable remnant of an army of 30,000 men, turning suddenly upon its victorious pursuers, dealt it blow after blow, the sun which seemed setting in darkness, again rose with new splendor upon the fortunes of these infant States.

Certainly the military, political, and moral effects of this brilliant finish to what had been a losing campaign, in which almost each succeeding day ushered in some new misfortune, were prodigious. But neither the importance nor the urgency of this masterly counter-stroke to the American cause can be at all appreciated, or even properly understood, unless what had gone before, what in fact had produced a crisis so dark and threatening, is brought fully into light. Washington himself says the act was prompted by a dire necessity. Coming from him, these words are full of meaning. We realize that the fate of the Revolution was staked upon this one last throw. If we would take the full measure of these words of his, spoken in the fullest conviction of their being final words, we must again go over the whole field, strewed with dead hopes, littered with exploded reputations, cumbered with cast-off traditions, over which the patriot army marched to its supreme trial out into the broad pathway which led to final success.

The campaign of 1776 is, therefore, far too instructive to be studied merely with reference to its crowning and concluding feature. In considering it the mind is irresistibly impelled toward one central, statuesque figure, rising high above the varying fortunes of the hour, like the Statue of Liberty out of the crash and roar of the surrounding storm.

Nowhere, we think, does Washington appear to such advantage as during this truly eventful campaign. Though sometimes troubled in spirit, he is always unshaken. Though his army was a miserable wreck, driven about at the will of the enemy, Washington was ever the rallying-point for the handful of officers and men who still surrounded him. If the cause was doomed to shipwreck, we feel that he would be the last to leave the wreck.

His letters, written at this trying period, are characterized by that same even tone, as they disclose in more prosperous times. He does not dare to be hopeful, yet he will not give up beaten. There is an atmosphere of stern, though dignified determination about him, at this trying hour, which, in a man of his admirable equipoise, is a thing for an enemy to beware of. In a word, Washington driven into a corner was doubly dangerous. And it is evident that his mind, roused to unwonted activity by the gravity of the crisis, the knowledge that all eyes turned to him, sought only for the opportune moment to show forth its full powers, and by a conception of genius dominate the storm of disaster around him.

Washington never claimed to be a man of destiny. He never had any nicknames among his soldiers. Napoleon was the "Little Corporal," "Marlborough" "Corporal John," Wellington the "Iron Duke," Grant the "Old Man," but there seems to have been something about the personality of Washington that forbade any thought of familiarity, even on the part of his trusty veterans. Yet their faith in him was such that, as Wellington once said of his Peninsular army, they would have gone anywhere with him, and he could have done anything with them.

THE CAMPAIGN OF TRENTON

NEW YORK THE SEAT OF WAR

New views of the war.

Upon finding that what had at first seemed only a local rebellion was spreading like wildfire throughout the length and breadth of the colonies, that bloodshed had united the people as one man, and that these people were everywhere getting ready for a most determined resistance, the British ministry awoke to the necessity of dealing with the revolt, in this its newer and more dangerous aspect, as a fact to be faced accordingly, and its military measures were, therefore, no longer directed to New England exclusively, but to the suppression of the rebellion as a whole. For this purpose New York was very judiciously chosen as the true base of operations.[1]

In the colonies, the news of great preparations then making in England to carry out this policy, inevitably led up to the same conclusions, but as the siege of Boston had not yet drawn to a close, very little could be done by way of making ready to meet this new and dangerous emergency.

We must now first look at the ways and means.

The new Continental Army.

A new army had been enlisted in the trenches before Boston to take the place of that first one, whose term of service expired with the new year, 1776. On paper it consisted of twenty-eight battalions, with an aggregate of 20,372 officers and men. By the actual returns, made up shortly before the army marched for New York, there were 13,145 men of all arms then enrolled, of whom not more than 9,500 were reported as fit for duty. These were all Continentals,[2] as the regular troops were then called, to distinguish them from the militia.

It marches to New York.

Immediately upon the evacuation of Boston by the British (March 17, 1776), the army marched by divisions to New York, the last brigade, with the commander-in-chief, leaving Cambridge on April 4.3 This move distinctly foreshadows the general opinion that the seat of war was about to be transferred to New York and its environs.

There is no need to discuss the general proposition, so quickly accepted by both belligerents, as regards the strategic value of New York for combined operations by land and sea. Hence the Americans were naturally unwilling to abandon it to the enemy. A successful defence was really beyond their abilities, however, against such a powerful fleet as was now coming to attack them, because this fleet could not be prevented from forcing its way into the upper bay without strong fortifications at the Narrows to stop it, and these the Americans did not have. Once in possession of the navigable waters, the enemy could cut off communication in every direction, as well as choose his own point of attack. Afraid, however, of the moral effect of giving up the city without a struggle, the Americans were led into the fatal error of squandering their resources upon a defence which could end only in one way, instead of holding the royal army besieged, as had been so successfully done at Boston.

Having arrived at New York, Washington's force was increased by the two or three thousand men who had been hastily summoned for its defence,[4] and who were then busily employed in throwing up works at various points, under the direction of the engineers.

Make-up of the army.

Now, it is usual to call such a large body of raw recruits, badly armed, and without discipline, an army, in the same breath as a well armed and thoroughly disciplined body. This one had done good service behind entrenchments, and in some minor operations at Boston had shown itself possessed of the best material, but the situation was now to be wholly reversed, the besiegers were to become the besieged, their mistakes were to be turned against them, the experiments of inexperience were to be tested at the risk of total failure, and the morale severely tried by the grumbling and discontent arising for the most part from laxity of discipline, but somewhat so, too, from the wretched administration of the various civil departments of the army.[5] The officers did not know how to instruct their men, and the men could not be made to take proper care of themselves. In consequence of this state of things, inseparable perhaps from the existing conditions, General Heath tells us that by the first week of August the number of sick amounted to near 10,000 men, who were to be met with lying "in almost every barn, stable, shed, and even under the fences and bushes," about the camps. This primary element of disintegration is always one of the worst possible to deal with in an army of citizen soldiers, and the present case proved no exception.

Except a troop of Connecticut light-horse, who had been curtly and imprudently dismissed because they showed sufficient esprit de corps to demur against doing guard duty as infantry, and whose absence was only too soon to be dearly atoned for, there was no cavalry, not even for patrols, outposts, or vedettes. These being thus of necessity drawn from the infantry, it was usual to see them come back into camp with the enemy close at their heels, instead of giving the alarm in season to get the troops under arms.

As for the infantry, it was truly a motley assemblage. A few of the regiments, raised in the cities, were tolerably well armed and equipped, and some few were in uniform. But in general they wore the same homespun in which they had left their homes, even to the field officers, who were only distinguished by their red cockades. In few regiments were the arms all of one kind, not a few had only a sprinkling of bayonets, while some companies, whom it had been found impracticable to furnish with fire-arms at the home rendezvous, carried the old-fashioned pikes of by-gone days. Among the good, bad, and indifferent, Washington had had two thousand militia poured in upon him, without any arms whatever. But these men could use pick and spade.

The single regiment of artillery this "rabble army," as Knox calls it, could boast was unquestionably its most reliable arm. Under Knox's able direction it was getting into fairly good shape, though the guns were of very light metal. In the early conflicts around New York it was rather too lavishly used, and suffered accordingly, but its efficiency was so marked as to draw forth the admission from a British officer of rank that the rebel artillery officers were at least equal to their own.

These plain facts speak for themselves. If radical defects of organization lay behind them, it was not the fault of Washington or the army, but is rather attributable to the want of any settled policy or firm grasp of the situation on the part of the Congress.

Washington had no illusions either with regard to himself or his soldiers. His letters of this date prove this. He was as well aware of his own shortcomings as a general, as of those of his men as soldiers. There could, perhaps, be no greater proof of the solidity of his judgment than this capacity to estimate himself correctly, free from all the prickings of personal vanity or popular praise. With reference to the army he probably thought that if raw militia would fight so well behind breastworks at Bunker Hill, they could be depended upon to do so elsewhere, under the same conditions. His idea, therefore, was to fight only in intrenched positions, and this was the general plan of campaign for 1776.[6]

II

PLANS FOR DEFENCE

Troops sent to Canada.

Washington's army had no sooner reached the Hudson than ten of the best battalions[1] were hurried off to Albany, if possible, to retrieve the disasters which had recently overwhelmed the army of Canada, where three generals, two of whom, Montgomery and Thomas, were of the highest promise, with upwards of 5,000 men, had been lost. The departure of these seasoned troops made a gap not easily filled, and should not be lost sight of in reckoning the effectiveness of what were left.

Strength of the army.

This large depletion was, however, more than made good, in numbers at least, by the reinforcements now arriving from the middle colonies, who, with troops forming the garrison of the city, presently raised the whole force under Washington's orders[2] to a much larger number than were ever assembled in one body again. A very large proportion, however, were militiamen, called out for a few weeks only, who indeed served to swell the ranks, without adding much real strength to the army.

Plans for defence.

It being fully decided upon that New York should be held, two entirely distinct sets of measures were found indispensable. First the city was commanded by Brooklyn Heights, rising at short cannon-shot across the East River. These heights were now being strongly fortified on the water-side against the enemy's fleet, and on the land-side against a possible attack by his land forces.[3]

New York in 1776.

The second measure looked to defending the city from an attack in the rear. At this time New York City occupied only a very small section of the southern part of the island which it has since outgrown. A few farms and country seats stretched up beyond Harlem, but the major part of the island was to the city below as the country to the town, retaining all its natural features of hill and dale unimpaired. At this time, too, the only exit from the island was by way of King's Bridge,[4] twelve miles above the city, where the great roads to Albany and New England turned off, the one to the north, the other to the east, making this passage fully as important in a military sense, as was the heavy drawbridge thrown across the moat of some ancient castle.

Fort Washington.

Fort Washington[5] was, therefore, built on a commanding height two and a half miles below King's Bridge, with outworks covering the approaches to the bridge, either by the country roads coming in from the north or from Harlem River at the east. These works were never finished, but even if they had been they could not solve the problem of a successful defence, because it lay always in the power of the strongest army to cut off all communication with the country beyond – and that means the passing in of reënforcements or supplies – by merely throwing itself across the roads just referred to. This done, the army in New York must either be shut up in the island, or come out and fight, provided the enemy had not already put it out of their power to do so by promptly seizing King's Bridge. And in that case there was no escape except by water, under fire of the enemy's ships of war.

One watchful eye, therefore, had to be kept constantly to the front, and another to the rear, between positions lying twelve to thirteen miles apart, and separated by a wide and deep river.

It thus appears that the defence of New York was a much more formidable task than had, at first, been supposed, and that an army of 40,000 men was none too large for the purpose, especially as it was wholly impracticable to reënforce King's Bridge from Brooklyn, or vice versa. But from one or another cause the army had fallen below 25,000 effectives by midsummer, counting also the militia, who formed a floating and most uncertain constituent of it. For the present, therefore, King's Bridge was held as an outpost, or until the enemy's plan of attack should be clearly developed; for whether Howe would first assail the works at Brooklyn, Bunker Hill fashion, or land his troops beyond King's Bridge, bringing them around by way of Long Island Sound, were questions most anxiously debated in the American camp.

However, the belief in a successful defence was much encouraged by the recent crushing defeat that the British fleet had met with in attempting to pass the American batteries at Charleston. Thrice welcome after the disasters of the unlucky Canada campaign, this success tended greatly to stiffen the backbone of the army, in the face of the steady and ominous accumulation of the British land and naval forces in the lower bay. Then again, the Declaration of Independence, read to every brigade in the army (July 9), was received with much enthusiasm. Now, for the first time since hostilities began, officers and men knew exactly what they were fighting for. There was at least an end to suspense, a term to all talk of compromise, and that was much.

The British army.

Thus matters stood in the American camps, when the British army that had been driven from Boston, heavily reënforced from Europe, and by calling in detachments from South Carolina, Florida, and the West Indies, so bringing the whole force in round numbers up to 30,000 men,6 cast anchor in the lower bay. Never before had such an armament been seen in American waters. Backed by this imposing display of force, royal commissioners had come to tender the olive branch, as it were, on the point of the bayonet. They were told, in effect, that those who have committed no crime want no pardon. Washington was next approached. As the representative soldier of the new nation, he refused to be addressed except by the title it had conferred upon him. The etiquette of the contest must be asserted in his person. Failing to find any common ground, upon which negotiations could proceed, resort was had to the bayonet again.

III

LONG ISLAND TAKEN

British move to L. Island.

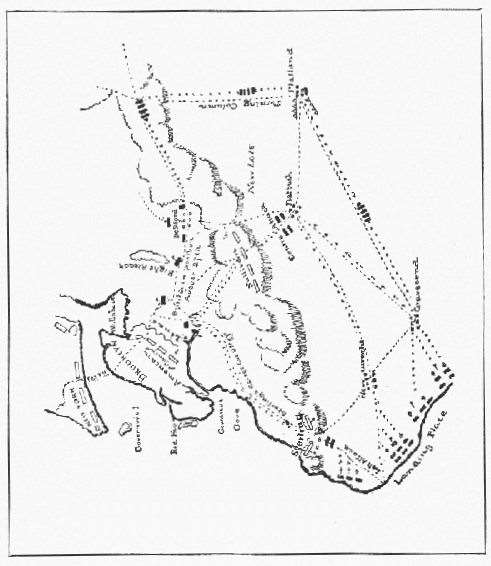

Up to August 22, the British army made no move from its camps at Staten Island. On their part, the Americans could only watch and wait. On this day, however, active operations began with the landing of Howe's troops, in great force, on the Long Island shore, opposite. This force immediately spread itself out through the neighboring villages from Gravesend, to Flatbush and Flatlands, driving the American skirmishers before them into a range of wooded hills,[1] which formed their outer line of defence. Howe had determined to attack in front, clearing the way as he went.

Plan of attack.

As the enemy would have to force his way across these hills, before he could reach the American intrenched lines around Brooklyn, all the roads leading over them were strongly guarded, except out at the extreme left, beyond Bedford village, where only a patrol was posted.[2] This fatal oversight, of which Howe was well informed, suggested the British plan of attack, which was quickly matured and successfully carried out. It included a demonstration on the American left, to draw attention to that point, while another corps was turning the right, at its unguarded point.

A third column was held in readiness to move upon the American centre from Flatbush, just as soon as the other attacks were well in progress. When the flanking corps was in position, these demonstrations were to be turned into real attacks, which, if successful, would throw the Americans back upon the flanking column, which, in its turn, would cut off their retreat to their intrenchments.

This clever combination, showing a perfect knowledge of the ground, worked exactly as planned.

By making a night march, the turning column got quite around the American flank and rear unperceived, and on the morning of the 27th was in position, near Bedford, at an early hour, waiting for the signal-guns to announce the beginning of the battle at the British left.

BATTLE OF LONG ISLAND.

Battle of Long Island.

Both columns then advanced to the attack. Being strongly posted, and well commanded, the Americans made an obstinate resistance and did hold the enemy in check for some hours at one end of the line, only to find themselves cut off by the hurried retreat of all the troops posted at the passes on their left; for as soon as the firing there showed that the turning column had come up in their rear, these troops, with great difficulty, fought their way back to the Brooklyn lines, leaving three generals and upwards of 1,000 men in the enemy's hands.

The resistance met with by the enemy's turning corps may be guessed from what an officer[3] who took part has to say of it. "We have had," he goes on to relate, "what some call a battle, but if it deserves that name it was the pleasantest I ever heard of, as we had not received more than a dozen shots from the enemy, when they ran away with the utmost precipitation."

Washington re-enforces.

Though not in personal command when the action began, Washington crossed over to Brooklyn in time to see his broken and dispirited battalions come streaming back into their works. Fearing the worst, he had called down two of his best regiments (Shee's and Magaw's) from Harlem Heights, and Glover's from the city, to reënforce the troops then engaged on Long Island, but as has already been pointed out, reënforcing in this manner was out of the question. By making a rapid march, the Harlem troops reached the ferry in the afternoon, after firing had ceased. They were, however, ferried across the next morning.

28th and 29th.

These movements would indicate a resolution to hold the Brooklyn lines at all hazards, and were so regarded, but during the two days subsequent to the battle, while the enemy was closing in upon him, Washington changed his mind, preparations were quietly made to withdraw the troops, while still keeping up a bold front to the enemy, and on the night of the 29th the army repassed the East River without accident or molestation.

Having thus cleared Long Island, the British extended themselves along the East River as far as Newtown, that river thus dividing the hostile camps throughout its whole extent. And though New York now lay quite at his mercy, Howe refrained from cannonading it, for the same reason as Washington did from shelling Boston; namely, that of securing the city intact a little later.

In spite of this brilliant opening of the campaign, and outside of the noisy subalterns who were making their début in war, it was felt that the British army, fresh, numerous, and splendidly equipped, had acquitted itself most ingloriously in permitting the Americans to make their retreat from the island as they had, when the event of an assault must probably have been most disastrous to them.

Losses so far.

On the other side defeat had seriously affected the morale of the Americans. Fifteen hundred men had been lost on Long Island. A great many more were now being lost through desertion. In Washington's own words the unruly militia left him by companies, half regiments or whole regiments, leaving the infection of their evil example to work its will among the well-disposed.

New York to be held.

Although the defence of New York had thus broken down at its vital point, a majority of generals favored still holding the city. To this end Washington now divided his forces, leaving 4,000 in the city, posting 6,500 at Harlem Heights, and 12,000 at Fort Washington and King's Bridge. Though furnished by a general officer,[4] these figures really include the sick, who were estimated at nearly 10,000, as well as the large number detached on extra duty. Washington, himself, vaguely estimated his effective force at under 20,000 at this time.

As thus arranged, Harlem Heights, in the centre, became the army headquarters for the time being, Washington, by one of those little accidents that sometimes arrest a passing thought, occupying the house[5] of the same lady who had formerly refused the offer of his hand in marriage, Miss Mary Phillipse, later to accept that of Colonel Roger Morris, his old companion in arms during Braddock's fatal campaign.

IV

NEW YORK EVACUATED

Howe seems to have thought that so long as Washington remained in New York he might be bagged at leisure. In no other way can his dilatory proceedings be accounted for. Sixteen days passed without any demonstration on his part whatever. Meantime, however, the steady extension of his lines toward Hell Gate had operated such a change of opinion in the American camp that the decision to hold the city was now reconsidered, and the evacuation fixed for September 15. It was seen that the storm centre was now shifting over toward the American communications, but just where it would break forth was still a matter of conjecture.