полная версия

полная версияThe William Henry Letters

"Harness in the colt, then," Aunt Phebe said. "No matter about their matching, if we only get there!"

That colt is about twenty years old. He's black, and short, and takes little stubby steps; and he's got a shaggy mane, that goes flop, flop, flop every step he takes. But Old Major is bony, and has a long neck, like the nose of a tunnel. Such a span as they made! What would my mother say to see that span!

They were harnessed in to the hay-cart. A hay-cart is a long cart that has stakes stuck in all round it. We put boards across for benches. Aunt Phebe brought out a whole armful of quite small flags, that they had Independent Day, and we tied one to the end of every stake.

Such a jolly time as we did have getting aboard! First all the baskets and pails full of cake and pies were stowed away under the benches, and jugs of water, and bottles of milk, and a hatchet, and some boiled eggs, and apples and pears. Then uncle called out, "Come! where is everybody? Tumble in! tumble in! Where's little Tommy?"

Then we began to look about and to call "Tommy!" "Tommy!" "Tommy!" At last Bubby Short said, "There he is, up there!" We all looked up, and saw Tommy's face part way through a broken square of glass – I mean where the glass was broken out. He said he couldn't "tum down, betause the roosted was on his feets." You see, he'd got his feet tangled up in Lucy Maria's worsteds.

"O dear!" Lucy Maria said; "all that shaded pink!"

When they brought him down, Uncle Jacob looked very sober, and said, "Why, Tommy! Did you get into all that shaded pink?"

"Didn't get in all of it," said Tommy. Then he told us he was taking down the "gimmerlut to blower a hole with." Next he began to cry for his new hat; and when he got his new hat, he began to cry for a posy to be stuck in it. That little fellow never will go anywhere without a flower stuck in his hat. Aunt Phebe says his grandmother began that notion when her damask rosebush was in bloom.

After we were all aboard, Uncle Jacob brought out the teakettle, and slung it on behind with a rope. He said maybe mother would want a cup of tea. Then they laughed at him, for he is the tea-drinker himself. Next he brought out a long pan.

"Now that's my cookie-pan!" Aunt Phebe said. "You don't cook clams in my cookie-pan!"

He made believe he was terribly afraid of Aunt Phebe, and trotted back with it just like a little boy, and then came bringing out an old sheet-iron fireboard.

"Is this anybody's cookie-pan?" said he, then stowed it away in the bottom of the cart. Bubby Short wanted to know what that was for.

"That's for the clams," Uncle Jacob said.

But we couldn't tell whether he meant so. We never can tell whether Uncle Jacob is funning or not. I haven't told you yet where we were bound. We were bound to the shore. That's about six miles off. The last thing that Uncle Jacob brought out was a stick that had strips of paper tied to the end of it.

"That's my flyflapper!" Aunt Phebe said. "What are you going to do with my flyflapper?"

He said that was to brush the snarls off little Tommy's face. Tommy is a tip-top little chap; but he's apt to make a fuss. Sometimes he teased to drive, and then he teased for a drink, and then for a sugar-cracker, and then to sit with Matilda, and then with Hannah Jane. And, every time he fretted, Uncle Jacob would take out the flyflapper, and play brush the snarls off his face, and say, "There they go! Pick 'em up! pick 'em up!" And that would set Tommy a-laughing. Tommy tumbled out once, the back end of the cart. Billy was driving, and he whipped up quick, and they started ahead, and sent Tommy out the back end, all in a heap. But first he stood on his head, for 't was quite a sandy place. I drove part of the way, and so did Bubby Short. We didn't hurrah any going. Some men that we met would laugh and call out, "What'll you take for your span?" And sometimes boys would turn round, and laugh, and holler out, "How are you, teakettle?" I think a hay-cart is the best thing to ride in that ever was. Just as we got through the woods, we looked round and saw Billy's father coming, bringing Billy's grandmother in a horse and chaise. Then we all clapped. For they said they guessed they couldn't come.

When we got to the shore the horses had to be hitched to the cart, for there wasn't a tree there, nor so much as a stump. Uncle Jacob called to us to come help him dig the clams. Billy carried the clam-digger, and I carried the bucket. Isn't it funny that clams live in the mud? How do you suppose they move round? Do you suppose they know anything? Uncle Jacob struck his clam-digger in everywhere where he saw holes in the mud; and as fast as he uncovered the clams we picked them up, and soon got the bucket full.

Then he told us to run like lamplighters along the shore, and pick up sticks and bits of boards. "Bring them where you see a smoke rising," says he.

O, such loads as we got, and split up the big pieces with the hatchet! Uncle Jacob had fixed some stones in a good way, and put his iron fireboard on top, and made a fire underneath. Then he spread his clams on the fireboard to roast. O, I tell you, sis, you never tasted of anything so good in your life as clams roasted on a fireboard!

And he put some stones together in another place, and set on the teakettle, and made a fire under it, – to make a cup of tea for mother, he said. Tommy kept helping making the fire, and once he joggled the teakettle over. Aunt Phebe and the girls sat on the rocks, the side where the wind wouldn't blow the smoke in their eyes. But Billy's grandmother had a soft seat made of sea-weed and the chaise cushions, and shawls all over her, and Billy's father read things out of the newspaper to her. He said they two were the invited guests, and mustn't work.

It took the girls ever so long to cut up the cakes and pies, and butter the biscuits. I know I never was so hungry before! The clams were passed round, piping hot, in box covers, and tin-pail covers, and some had to have shingles. You'd better believe those clams tasted good! Then all the other things were passed round. O, I don't believe any other woman can make things as good as Aunt Phebe's! Georgianna had a frosted plum-cake baked in a saucer; and, every time she moved her seat, Uncle Jacob would go too, and sit close up to her, and say how much he liked Georgie, she was the best little girl that ever was, – a great deal better than Aunt Phebe's girls. Then Georgianna would say, "O, I know you! you want my frosted cake!" Then Uncle Jacob would pucker his lips together, and shut up his eyes, and shake his head so solemn! He keeps every body a-laughing, even Billy's grandmother. He was just as clever to her! picked out the best mug there was to put her tea in, – Aunt Phebe don't carry her good dishes, they get broken so, – and shocked out the clams for her in a saucer. When you get this letter, I guess you'll get a good long one. After dinner we scattered about the shore. 'T was fun to see the crabs and frys and things the tide had left in the little pools of water. And I found lots of blanc-mange moss. We boys ran ever so far along shore, and went in swimming. The water wasn't very cold.

When it was time to go home, Uncle Jacob drummed loud on the six-quart pail, and waved his handkerchief. And the wind took it out of his hand, and blew it off on the water. Billy said, "Now the fishes can have a pocket-handkerchief." And that made little Tommy laugh. Tommy had been in wading without his trousers being rolled up, and got 'em sopping wet. Just as we were going to leave, a sail-boat went past, quite near the shore, with a party on board. We gave them three cheers, and they gave us three cheers and a tiger; then they waved, and then we waved. Uncle Jacob hadn't any pocket-handkerchief, so he caught Georgianna up in his arms, with her white sunbonnet on, and waved her; then the people in the boat clapped.

O, we had a jolly time coming home! In the woods we all got out and rested the horses, and I came pretty near catching a little striped squirrel. I should give it to you if I had. Did you ever see any live fences? Fences that branch out, and have leaves grow on them? Now I suppose you don't believe that! But it's true, for I've seen them. In the woods, if they want to fence off a piece, they don't go to work and build a fence, but they bend down young trees, or the branches of trees, and fasten them to the next, and so on as far as they want the fence to go. And these trees and branches keep growing, and look so funny, something like giants with their legs and arms all twisted about. And every spring they leaf out the same as other trees, and that makes a real live fence. My squirrel was on that kind of fence. I wish it was my squirrel. He had a striped back. I got close up to him that is, I got quite close up, – near enough to see his eyes. What things they are to run!

Coming home we sang songs, and laughed; and every time we came to a house we cheered all together, and waved our flags. Everybody came to their windows to look, for there isn't much travelling on that road. O, I'm so out of breath, and so hoarse! But I'm sorry we've got home, I wish it had been ten miles. Now I hear them laughing and clapping over at Aunt Phebe's. What can they be doing? Now Uncle Jacob is calling us to come over. Bubby Short's jumped up. He says his throat feels better now. I wonder what Uncle Jacob wants of us. We must go and see. Good by, sis. This letter is from your

Brother Dorry.-I remember what they were clapping about. It happened that I came out from the city that day. The weather was so fine, I felt as if I must take one more look at the country, before winter came and spoiled every bright leaf and flower. I think the flowers and leaves seem very precious in the fall, when we know frost is waiting to kill them.

It was quite a disappointment to find the people all gone, and I was glad enough when at last the old hay-cart came rattling down the lane. Such a jolly set as they were! I jumped them out at the back of the cart.

That little Tommy was always such a funny chap. Just like his father for all the world. When the girls took their things off, he got himself into an old sack, and then tied on one of his mother's checked aprons, and began to parade round. When Lucy Maria saw him she took him up stairs and put more things on him, and dressed him up for Mother Goose. I don't know when I've seen anything so droll. They put skirts on him, till they made him look like a little fat old woman. He had a black silk handkerchief pinned over his shoulders, and a ruffle round his neck, and an old-fashioned, high-crowned nightcap on. Then spectacles. They put a peaked piece of dough on the end of his nose, to make it look like a hooked nose, and then set him down in the arm-chair. He kept sober as a judge. Bubby Short laughed till he tumbled down and rolled himself across the floor. Lucy Maria sent us out of the room to see something in the yard, and when we came back, there was a little old man with his hat on, and a cane, sitting opposite Mother Goose. He was made of a stuffed-out overcoat, trousers with sticks of wood in them, and boots. "That is Father Goose," Lucy Maria said. Then Bubby Short had to tumble down again; and this time he rolled way through the entry, out on the doorstep!

Then came such a pleasant evening! Aunt Phebe said 't was a pity for Grandmother to go to getting supper, they might as well all come over. Where anybody had to boil the teakettle and set the table, half a dozen more or less didn't matter much.

So we all ate supper together, and it seemed to me I never did get into such a jolly set! Uncle Jacob and Aunt Phebe were so funny that we could hardly eat. And in the evening – But 't is no use. If I begin to tell, and tell all I want to, there won't be any room left for the letters.

Now comes quite a gap in the correspondence. There must have been many letters written about this time, which were, unfortunately not preserved. The next in order I find to be a short epistle from Bubby Short, written, it would seem, soon after the winter holidays.

A Letter from Bubby Short

Dear Billy, —

My mother is all the one that I ever wrote a letter to before. So excuse poor writing, and this pen isn't a very good pen to write with I bet. I am very sorry that you can't come back quite yet. I hope that it won't be a fever that you are going to have. Does your grandma think that 't is going to be a fever? Do you take bitter medicine? I never had a fever. I take little pills every time I have anything. My mother likes little pills best now. But she used to make me take bitter stuff. Once she put it in my mouth and I wouldn't swallow it down. Then she pinched my nose together and it made me swallow it down. Once I ate up all the little pills out of the bottle, and she was very scared about it. It wasn't very full. But the doctor said that it wouldn't hurt me any if I did eat them. How many presents did you have? I had five. Dorry he says he hopes that it won't be a slow fever that you are going to have if you do have any fever, for he wants you to hurry and come back. Some new fellows have come. One is a tip-top one. And one good "pitcher." I hope you will come back very soon, 'cause I like you very much.

Do you know who 't is writing? I am that one all you fellers call

Bubby Short.-As may be gathered from the foregoing letter, William Henry did not go back to school with the rest. He was taken ill just at the close of vacation, and remained at home until spring. Grandmother said it was such a comfort that it didn't happen away. And it seemed to me that this thought really made her enjoy his being sick at home.

Indeed, the people at Summer Sweeting place seemed ready to get enjoyment from everything, even from gruel, which is usually considered flat. I passed a day there at a time when William Henry was subsisting on this very simple but wholesome food. Aunt Phebe and Uncle Jacob came in to take tea at grandmother's. The old lady was bringing out her nice things to set on the table, when Aunt Phebe said suddenly, I suppose seeing a hungry look in Billy's eyes. She said, —

"Now, Grandmother, I wouldn't bring those out. Let's have a gruel supper, and all fare alike! We'll make it in different ways, – milk porridge, oatmeal, corn-starch, – and I think 't will be a pleasant change."

"Gruel is very nourishing, well made," said Grandmother; "but what will Mr. Fry say?"

"Mr. Fry will say," I answered, "that milk porridge, with Boston crackers, is a dish fit for a king."

"I'm afraid Jacob won't think he's been to supper," said Grandmother.

"O yes," said Uncle Jacob, "I'll think I have at any rate. But I like mine the way the man in the moon did his, or part of the way."

"Yes," said Aunt Phebe, "I understand! The last part – the 'plum' part!"

"O, don't all eat gruel for me," said Billy. "Course I sha' n't be a baby, and cry for things!"

But Aunt Phebe seemed resolved to develop the gruel idea to its utmost. She made all kinds, – Indian meal, oatmeal, corn-starch, flour, mixed meals, wheat; made it sweetened, and spiced with plums, and plain. One kind, that she called "thickened milk," was delicious. "Course" we had one cup of tea, and bread and butter, and I can truly say that I have eaten many a worse supper than a "gruel supper."

Here is a letter from William Henry to Dorry, written when he began to get well: —

William Henry's Letter to Dorry

Dear Dorry, —

I'm just as hungry as anything, now, about all the time. My grandmother says she's so glad to see me eat again; and so am I glad to eat myself. Things taste better than they did before. Maybe I shall come back to school again pretty soon, my father says; but my grandmother guesses not very, because she thinks I should have a relapse if I did. A relapse is to get sick when you're getting well; and, if I should get sick again, O what should I do! for I want to go out-doors. If they'd only let me go out, I'd saw wood all day, or anything. There isn't much fun in being sick, I tell you, Dorry; but getting well, O, that's the thing! I tell you getting well's jolly! I have very good things sent to me about every day, and when I want to make molasses candy my grandmother says yes every time, if she isn't frying anything in the spider herself; and then I wait and whistle to my sister's canary-bird, or else look out the window. But she tells me to stand a yard back, because she says cold comes in the window-cracks: and my uncle Jacob he took the yardstick one day, and measured a yard, and put a chalk mark there, where my toes must come to, he said. If I hold the yardstick a foot and a half up from the floor, my sister's kitty can jump over it tip-top. My sister has made a Red-Riding-Hood cloak for her kitty, and a muff to put her fore paws in, and takes her out.

Yesterday Uncle Jacob came into the house and said he had brought a carriage to carry me over to Aunt Phebe's; and when I looked out it wasn't anything but a wheelbarrow. My grandmother said I must wrap up, for 't was the first time; so she put two overcoats on me, and my father's long stockings over my shoes and stockings, and a good many comforters, and then a great shawl over my head so I needn't breathe the air; and 't was about as bad as to stay in. Uncle Jacob asked her if there was a Billy in that bundle, when he saw it. "Hallo, in there!" says he. "Hallo, out there!" says I. Then he took me up in his arms, and carried me out, and doubled me up, and put me down in the wheelbarrow, and threw the buffalo over me; but one leg got undoubled, and fell out, so I had to drag my foot most all the way. Aunt Phebe undid me, and set me close to the fire; and Lucy Maria and the rest of them brought me story-books and picture-papers; and Tommy, he kept round me all the time, making me whittle him out little boats out of a shingle, and we had some fun sailing 'em in a milk-pan. Aunt Phebe had chicken broth for dinner, and I had a very good appetite. She let me look into all her closets and boxes, and let me open all her drawers. But I had to have a little white blanket pinned on when I went round, because she was afraid her room wasn't kept so warm as my grandmother's. Soon as Uncle Jacob came in and saw that little white blanket he began to laugh. "So Aunt Phebe has got out the signal of distress," says he. He calls that blanket the "signal of distress," because when any of them don't feel well, or have the toothache or anything, she puts it on them. She says he shall have to wear it some time, and I guess he'll look funny, he's so tall, with it on. The fellers played base-ball close to Aunt Phebe's garden. I tell you I shall be glad enough to get out-doors. I tell you it isn't much fun to look out the window and see 'em play ball. But Uncle Jacob says if the ball hit me 't would knock me over now. Aunt Phebe was just as clever, and let me whittle right on the floor, and didn't care a mite. And we made corn-balls. But the best fun was finding things, when I was rummaging. I found some pictures in an old trunk that she said I might have, and I want you to give them to Bubby Short to put in the Panorama he said he was going to make. He said the price to see it would be two cents. They are true ones, for they are about Aunt Phebe's little Tommy. One day, when he was a good deal smaller feller than he is now, he went out when it had done raining one day, and the wind blew hard, and he found an old umbrella, and did just what is in the pictures. The school-teacher that boarded there, O, she could draw cows and pigs and anything; and she drew these pictures, and wrote about them underneath.

I wish you would write me a letter, and tell Benjie to and Bubby Short.

From your affectionate friend,William Henry.P. S. What are you fellers playing now?

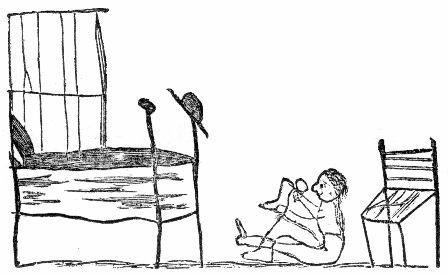

-Thinking the school-teacher's pictures might please other little Tommys, I have taken some pains to procure them for insertion here. Little "fellers" usually are fond of carrying umbrellas, – large size preferred. Nothing suited Tommy better than marching off to school of a rainy day with one up full spread, provided he could hold it. His cousin Myra once took an old umbrella and cut it down into a small one, by chopping off the ends of the sticks, supposing he would be delighted with it. But no, he wanted a "man's one."

TOMMY ON HIS TRAVELSTommy sets forth upon his travels around the house, taking with him his whip.

At the first corner he picks up an umbrella. A larger boy opens the umbrella, and shows him the way to hold it. Being an old umbrella, it shuts down again. But Tommy still keeps on in his way.

At the second corner a gust of wind takes down the umbrella, and blows his capes over his head. He pushes on, however, whip in hand, dragging the umbrella behind him.

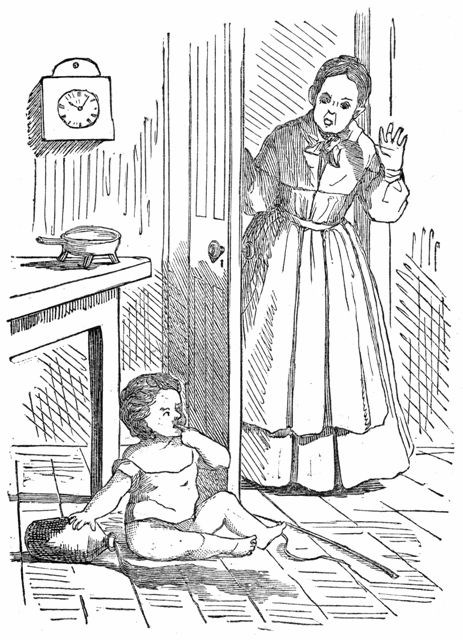

On turning the third corner a hen runs between his legs, and throws him down in the mud.

He is taken inside, stripped and washed, and left sitting upon the floor in his knit shirt, waiting for clean clothes. He can reach the handle of the molasses-jug. He does reach the handle, and tips over the jug. His mother finds him eating molasses off the floor with his forefinger. Tommy looks up with a sweet smile.

Here we have William Henry back at school again.

William Henry to his Grandmother

My dear Grandmother, —

I've been here three days now. I came safe all the way, but that glass vial you put that medicine into, down in the corner of the trunk, broke, and some white stockings down there, they soaked it all up; but I sha' n't have to take it now, and no matter, I guess, for I feel well, all but my legs feeling weak so I can't run hardly any. When I got here, the boys were playing ball; but they all ran to shake hands, and slapped my shoulders so they almost slapped me down, and hollered out, "How are you, Billy?" "How fares ye?" "Welcome back!" "Got well?" "Good for you, Billy!" Gus Beals – he's the great tall one we call "Mr. Augustus" – he called out, "How are you, red-top?" And then Dorry called out to him, "How are you, hay-pole?" Dorry and Bubby Short want me to tell you to thank Aunt Phebe for their doughnuts, and you, too, for that molasses candy. The candy got soft, and the paper jammed itself all into the candy, but Bubby Short says he loves paper when it has molasses candy all over it. I gave some of the things to Benjie. Something hurt me all the way coming, in the toe of my boot; and when I got here I looked, and 't was a five-cent piece right in the toe! I know who 't was! 'T was Uncle Jacob when he made believe look to see if that boot-top wasn't made of mighty poor leather. I went to spend it yesterday, down to the Two Betseys' shop. Lame Betsey called me a poor little dear, and was just going to kiss me, but I twisted my face round. I'm too big for all that now, I guess. She looked for something to give me, and was just going to give me a stick of candy; but the other Betsey said 't was no use to give little boys candy, for they'd only swallow it right down, so she gave me a row of pins, for she said pins were proper handy things when your buttons ripped off. Just when I was coming back from the Two Betseys' shop I met Gapper Skyblue. He goes about selling cakes now. A good many boys were round him, in a hurry to buy first, and all you could hear was, "Here, Gapper!"

"This way, Gapper!" "You know me, Gapper!" "Me, me, me!" One boy – he's a new boy – spoke up loud and said, "Mr. Skyblue, please attend to me, if you please, for I have five pennies to spend!" He came from Jersey. The fellers call him "Old Wonder Boy," because he brags and tells such big stories. But now, just as soon as he begins to tell, Dorry begins too, and always tells the biggest, – makes them up, you know. O, I tell you, Dorry gives it to him good! You'd die a laughing to hear Dorry, and so do all the fellers. W. B., – that's what we call Old Wonder Boy sometimes, – W stands for Wonder, and B stands for Boy, – he says cents are not cents; says they are pennies, for the Jersey folks call them pennies, and he guesses they know. He says he gets his double handful of pennies to spend every day down in Jersey. But Bubby Short says he knows that's a whopper, for he knows there wouldn't anybody's mother give them their double handful of pennies to spend every day, nor cents either, nor their father either. And then Dorry told Old Wonder Boy that he supposed it took his double handful of pennies to buy a roll of lozenges down in Jersey. Then W. B. said that our lozenges were all flour and water, but down in Jersey they were clear sugar, and just as plenty as huckleberries. Dorry said he didn't believe any huckleberries grew out there, or if they did, they'd be nothing but red ones, for the ground was red out in Jersey. But W. B. said no matter if the ground was red, the huckleberries were just as black as Yankee huckleberries, and blacker too, and three times bigger, and ten times thicker. Said he picked twenty quarts one day.