полная версия

полная версияThe William Henry Letters

Grandmother's Letter to William Henry, in reply

My dear Little Boy, —

Your poor old grandmother was so glad to get those letters, after such long waiting! My dear child, we were anxious; but now we are pleased. I was afraid you were down with the measles, for they're about. Your aunt Phebe thinks you had 'em when you were a month old; but I know better.

Your father was anxious himself at not hearing; though he didn't show it any. But I could see it plain enough. As soon as he brought the letters in, I set a light in the window to let your aunt Phebe know she was wanted. She came running across the yard, all of a breeze. You know how your aunt Phebe always comes running in.

"What is it?" says she. "Letters from Billy? I mistrusted 't was letters from Billy. In his own handwriting? Must have had 'em pretty light. Measles commonly leave the eyes very bad."

But you know how your aunt Phebe goes running on. Your father came in, and sat down in his rocking-chair, – your mother's chair, dear. Your sister was sewing on her doll's cloak by the little table. She sews remarkably well for a little girl.

"Now, Phebe," says I, "read loud, and do speak every word plain." I put on my glasses, and drew close up, for she does speak her words so fast. I have to look her right in the face.

At the beginning, where you speak about being whipped, your father's rocking-chair stopped stock still. You might have heard a pin drop. Georgianna said, "O dear!" and down dropped the doll's cloak. "Pshaw!" said Aunt Phebe, "'t isn't very likely our Billy's been whipped."

Then she read on and on, and not one of us spoke. Your father kept his arms folded up, and never raised his eyes. I had to look away, towards the last, for I couldn't see through my glasses. Georgianna cried. And, when the end came, we all wiped our eyes.

"Now what's the use," said Aunt Phebe, "for folks to cry before they're hurt?"

"But you almost cried yourself," said Georgianna. "Your voice was different, and your nose is red now." And that was true.

After your sister was in bed, and Aunt Phebe gone, your father says to me: "Grandma, the boy's like his mother." And he took a walk around the place, and then went off to his bedroom without even opening his night's paper. If ever a man set store by his boy, that man is your father. And, O Billy, if you had done anything mean, or disgraced yourself in any way, what a dreadful blow 't would have been to us all!

The measles come with a cough. The first thing is to drive 'em out. Get a nurse. That is, if you catch them. They're a natural sickness, and one sensible old woman is better than half a dozen doctors. Saffron's good to drive 'em out.

Aunt Phebe is knitting you a comforter. As if she hadn't family enough of her own to do for!

From your lovingGrandmother.-I think this the proper place to insert the following letter from Dorry Baker to his sister. I am sorry we have so few of Dorry's letters. Two very entertaining ones will be given presently, describing a visit Dorry made to William Henry's home. The two boys, as we shall see, soon after their acquaintance, grew to be remarkably good friends. Mr. Baker, Dorry's father, hearing his son's glowing accounts of William Henry's family, took a little trip to Summer Sweeting place on purpose to see them, and was so well pleased with Grandmother, Mr. Carver, Uncle Jacob, and the rest, as to suggest to his wife that they should buy some land in the vicinity, and turn farmers. He and Grandmother had a very pleasant talk about their boys; and not long after, knowing, I suppose, that it would gratify the old lady, he sent her some of Dorry's letters, that she might have the pleasure of reading for herself what Dorry had written about her Billy, and about Billy's people and Billy's home. Perhaps, too, Mr. Baker was a little bit proud of the smart letters his son could write.

Dorry's Letter to his Sister

Dear Sis, —

If mother's real clever, I want you to ask her something right away. But if it's baking-day, or washing-day, or company's coming off, or preserves going on, or anything's upset down below; or if she's got a headache or a dress-maker, or anything else that's bad, – then wait.

I want you to ask her if I may bring home a boy to spend Saturday. Not a very big boy, – do very well to "Philopene" with you: won't put her out a bit.

If you don't like him at first, you will afterwards. When he first came we used to plague him on account of his looks. He's got a furious head of hair, and freckles. But we don't think at all about his looks now. If anything, we like his looks.

He's just as pleasant and gen'rous, and not a mean thing about him. I don't believe he would tell a lie to save his life. I know he wouldn't. He's always willing to help everybody. And had just as lief give anything away as not. And when he plays, he plays fair. Some boys cheat to make their side beat. You don't catch William Henry at any such mean business. All the boys believe every word he says. Teachers too.

I will tell you how he made me ashamed of myself. Me and some other boys.

One day he had a box come from home. 'T was his birthday. It was full of good things. Says I to the boys, "Now, maybe, if we hadn't plagued him so, he would give us some of his goodies."

That very afternoon, when we had done playing, and ran up to brush the mud off our trousers, we found a table all spread out with a table-cloth that he had borrowed, and in the middle was a frosted cake with "W. H." on top done in red sugar. And close to that were some oranges, and a dish full of nuts, and as much as a pound of candy, and more figs than that, and four great cakes of maple-sugar, made on his father's land, as big as small johnny-cakes, and another kind of cake. And doughnuts.

"Come, boys," says he, "help yourselves."

But not a boy stirred.

I felt my face a-blushing like everything. O, we were all of us just as ashamed as we could be! We didn't dare go near the table. But he kept inviting us, and at last began to pass them round.

And I tell you the things were tip-top and more too. Such cake! And doughnuts, that his cousin made! And tarts! You must learn how. But I don't believe you ever could. Of course we had manners enough not to take as much as we wanted. I want to tell you some more things about him. But wait till I come. He's most as old as you are, and is always a laughing, the same as you are.

Ask mother what I told you. Take her at her cleverest, and don't eat up all the sweet apples.

From your brother,Dorry.P. S. Put some away in meal to mellow. Don't mellow 'em with your knuckles.

-Mrs. Baker, I imagine, was not particularly fond of boys. She gave her permission, however, for Dorry to bring a "muddy-shoed" companion home with him, as we see by the following letter from William Henry to his grandmother.

A Letter from William Henry

My dear Grandmother, —

Dorry asked his sister to ask his mother if he might ask me to go home with him. And she said yes; but to wait a week first, because the house was just got ready to have a great party, and she couldn't stand two muddy-shoed boys. May I go?

Tom Cush was sent home; but he didn't go. His father lives in the same town that Dorry does. He has been here to look for him.

I never went to make anybody a visit. I hope you will say yes. I should like to have some money. Everybody tells boys not to spend money; but if they knew how many things boys want, and everything tasted so good, I believe they would spend money themselves. Please write soon.

From your affectionate grandchild,William Henry.-To this short letter Grandmother sent at once the following reply; and in the succeeding letters from William Henry we get a pretty good idea of what sort of people Dorry's folks were, and also hear something about Tom Cush.

Grandmother's Second Letter

My dear Boy, —

Do you have clothes enough on your bed? Ask for an extra blanket. I do hope you will take care of yourself. When the rain beats against the windows, I think, "Now who will see that he stands at the fire and dries himself?" And you're very apt to hoarse up nights. We are willing you should go to see Dorry. Your uncle J. has been past his father's place, and he says there's been a pretty sum of money laid out there. Behave well. Wear your best clothes. Your aunt Phebe has bought a book for her girls that tells them how to behave. It is for boys too, or for anybody. I shall give you a little advice, and mix some of the book in with it.

Never interrupt. Some children are always putting themselves forward when grown people are talking. Put "sir" or "ma'am" to everything you say. Make a bow when introduced. If you don't know how, try it at a looking-glass. Black your shoes, and toe out if you possibly can. I hope you know enough to say "Thank you," and when to say it. Take your hat off, without fail, and step softly, and wipe your feet.

Be sure and have some woman look at you before you start, to see that you are all right. Behave properly at table. The best way will be to watch and see how others do. But don't stare. There is a way of looking without seeming to look. A sideways way.

Anybody with common sense will soon learn how to conduct properly; and even if you should make a mistake, when trying to do your best, it isn't worth while to feel very much ashamed. Wrong actions are the ones to be ashamed of. And let me say now, once for all, never be ashamed because your father is a farmer and works with his hands. Your father's a man to be proud of; he is kind to the poor; he is pleasant in his family; he is honest in his business; he reads high kind of books; he's a kind, noble Christian man; and Dorry's father can't be more than all this, let him own as much property as he may.

I mention this because young folks are apt to think a great deal more of a man that has money.

Your aunt Phebe wants to know if you won't write home from Dorry's, because her Matilda wants a stamp from that post-office. If the colt brings a very good price, you may get a very good answer to your riddle.

From your lovingGrandmother.P. S. Take your overcoat on your arm. When you come away, bid good by, and say that you have had a good time. If you have had, – not without.

William Henry's Reply

Dear Grandmother, —

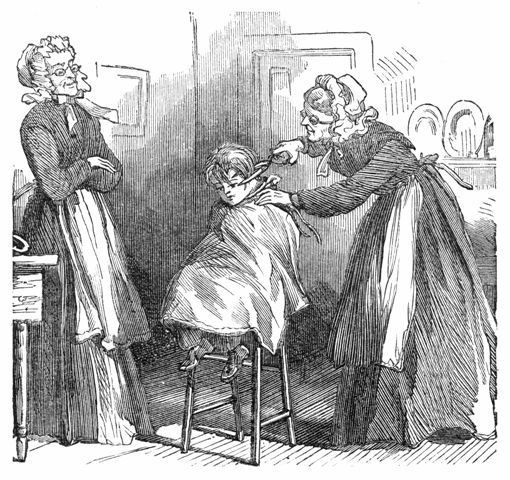

I am here. The master let us off yesterday noon, and we got here before supper, and this is Saturday night, and I have minded all the things that you said. I got all ready and went down to the Two Betseys to let some woman look at me, as you wrote. They put on both their spectacles and looked me all over, and picked off some dirt-specks, and made me gallus up one leg of my trousers shorter, and make some bows, and then walk across the room slow.

They thought I looked beautiful, only my hair was too long. Lame Betsey said she used to be the beater for cutting hair, and she tied her apron round my throat, and brought a great pair of shears out, that she used to go a-tailoring with. The Other Betsey, she kept watch to see when both sides looked even.

Lame Betsey tried very hard. First she stood off to look, and then she stood on again. She said her mother used to keep a quart-bowl on purpose to cut her boys' hairs with; she clapped it over their heads, and then clipped all round by it even. The shears were jolly shears, only they couldn't stop themselves easy, and the apron had been where snuff was, and made me sneeze in the wrong place. Says I, "If you'll only take off this apron, I'll jump up and shake myself out even." I'm so glad I'm a boy. Aprons are horrid. So are apron-strings, Dorry says.

They gave me a few peppermints, and said to be sure not to run my head out and get it knocked off in the cars, and not to get out till we stopped going, and to beware of pickpockets.

O, we did have a jolly ride in the cars! Do you think my father would let me be the boy that sells papers in the cars? I wish he would. I didn't see any pickpockets. We got out two miles before we got there. I mean to the right station. For Dorry wanted to make his sister Maggie think we hadn't come.

We took a short cut through the fields. Not very short. And went through everything. My best clothes too. But I guess 't will all rub off. There were some boggy places.

When we came out at Dorry's house, it was in the back yard. I said to Dorry, "There's your mother on the doorstep. She looks clever."

Dorry said, "She? She's the cook. I'll tell mother of that. No, I won't neither."

I suppose he saw I'd rather he wouldn't. The cook said everybody had gone out. Then Dorry took me into a jolly great room and left me. Three kinds of curtains to every window! What's the use of that? Gilt spots on the paper, and gilt things hanging down from up above. A good many kinds of chairs. I was going to sit down, but they kept sinking in. Everything sinks in here. I tried three, and this made me laugh, for I seemed to myself like the little boy that went to the bears' house and tried their chairs, and their beds, and their bowls of milk. Then I came to a looking-glass big enough for the very biggest bear. I thought I would make some bows before it, as you said. I was afraid I couldn't make a bow and toe out at the same time. Because it is hard to think up and down both at once. While I was trying to, I heard a little noise, I looked round, and – what do you think? Bears? O no. Not bears. A queen and a princess, I thought. All over bright colors and feathers and shiny silks. The queen – that's Dorry's mother you know, – couldn't think who I was, because they had been to the depot, and thought we hadn't come. So she looked at me hard, and I suppose I was very muddy. And she said, "Were you sent of an errand here?" Before I could make up any answer, Dorry came in. He had some cake, and he passed it round with a very sober face. Then he introduced me, and I made quite a good bow, and said, "Very well, I thank you, ma'am."

I tried to pull my feet behind me, and wished I was sitting down, for she kept looking towards them; and I wanted to sit down on the lounge, but I was afraid 't wouldn't bear. She was quite glad to see Dorry. But didn't hug him very hard. I know why. Because she had those good things on. Dorry's grandmother lives here. She can't bear to hear a door slam. She wears her black silk dress every day. And her best cap too. 'T is a stunner of a cap. White as anything. And a good deal of white strings to it. Everything makes her head ache. I'd a good deal rather have you. When boys come nigh, she puts her hand out to keep them off. This is because she has nerves. Dorry says his mother has 'em sometimes. I like his father. Because he talks to me some. But he's very tired. His office tires him. He isn't a very big man. He doesn't laugh any. If Maggie was a boy she'd be jolly. She'll fly kites, or anything, if her mother isn't looking. Her mother don't seem a bit like Aunt Phebe. I don't believe she could lift a teakettle. Not a real one. When she catches hold of her fork, she sticks her little finger right up in the air. She makes very pretty bows to the company. Sinks way down, almost out of sight. She gave us a dollar to spend; wasn't she clever? Dorry says she likes him tip-top. If he'll only keep out of the way.

I guess I'd rather live at our house. About every room in this house is too good for a boy. But I tell you they have tip-top things here. Great pictures and silver dishes! Now, I'll tell you what I mean to do when I'm a man. I shall have a great nice house like this, and nice things in it. But the folks shall be like our folks. I shall have horses, and a good many silver dishes. And great pictures, and gilt books for children that come a-visiting. And you shall have a blue easy-chair, and sit down to rest.

Now, maybe you'll say, "But, Billy, Billy, where are you going to get all these fine things?" O you silly grandmother! Don't you remember your own saying that you wrote down? – "What a man wants he can get, if he tries hard enough." Or a boy either, you said. I shall try hard enough. There's more to write about. But I'm sleepy. I would tell you about Tom Cush's father coming here, only my eyes can't keep open. Isn't it funny that when you are sleepy your eyes keep shutting up and your mouth keeps coming open? Please excuse the lines that go crooked. There's another gape! I guess Aunt Phebe will be tired reading all this. I'm on her side. I mean about measles. I'd rather have 'em when I was a month old. I suppose I was a month old once. Don't seem as if 't was the same one I am now. But if I do have 'em, – there I go gaping again, – if I catch 'em, and all the doctors do come, I'll – O dear! There I go again. I do believe I'm asleep – I'll – I'll get some natural-born old woman to drive 'em out, as you said, and good night.

William Henry.-My dear Grandmother, —

I am back again, and had a good time; but came back hungry. I'll tell you why. The first time I sat down to table I felt bashful, and Dorry's mother said a great deal about my having a small appetite, and afterwards I didn't like to make her think it was a large one.

I guess I behaved quite well at the table. But I couldn't look the way you said. It made me feel squint-eyed. Once I almost laughed at table. The day they had roast duck, it smelt nice. I thought it wouldn't go round, for they had company besides me; and I said, "No, I thank you, ma'am." Dorry whispered to me, "You must be a goose not to love duck"; and that was when I almost laughed at table. His grandmother shook her head at him.

Now I'll tell about Tom Cush's father. That Saturday, when we were eating dinner, somebody came to the front door, and inquired for us two, – Dorry and me. It was Tom Cush's father. He wanted to ask us about Tom, and whether we knew anything about him. But we knew no more than he did. He talked some with us. The next evening, – Sunday evening, – Tom Cush's mother sent for Dorry and me to come and see her. His father came after us. She said they wanted to know more about what I wrote to you in those letters.

O, I don't want ever again to go where the folks are so sober. The room was just as still as anything, not much light burning, and great curtains hanging way down, and she looked like a sick woman. Just as pale! Only sometimes she stood up and walked, and then sat down again, and leaned way forward, and asked a question, and looked into our faces so. We didn't know what to do. Dorry talked more than I could. Tom's father kept just as sober! He said to Dorry: "It is true, then, that my boy wouldn't own up to his own actions?" or something like that.

Dorry said, "Yes, sir."

Tom's father said, "And he was willing to sit still and see another boy whipped in his place?"

"Yes, sir," Dorry said. But he didn't say it very loud.

Then they stopped asking questions, and not one of us spoke for ever so long. O, 't was so still! At last Dorry said, just as softly, "Can't you find him anywhere?" And then I said that I didn't believe he was lost.

Then Tom's father got up from his chair and said, "Lost? That's not it. That's not it. 'T is his not being honorable! 'T is his not being true! Lost? Why, he was lost before he left the school." Says he: "When he did a mean thing, then he lost himself. For he lost his truth. He lost his honor. There's nothing left worth having when they are gone."

O, I never saw Dorry so sober as he was that night going home. And when we went to bed, he hardly spoke a word, and didn't throw pillows, or anything. I shut my eyes up tight and thought about you all at home, and Aunt Phebe, and Aunt Phebe's little Tommy, and about school, and about Bubby Short, and all the time Tom's mother's eyes kept looking at me just as they did; and when I was asleep I seemed back again in that lonesome room, and they two sitting there.

From your affectionate grandchild,William Henry.P. S. I want to tell that when I was at Dorry's I let a little vase fall down and break. I didn't think it was so rotten. I felt sorry; but didn't say so; I didn't know how to say it very well. I wish grown-up folks would know that boys feel sorry very often when they don't say so, and sometimes they think about doing right, too. And mean to, but don't tell of it. Next time I shall tell about Bubby Short and me going to ride in Gapper's donkey-cart. He's going to lend it to us. I should like to buy them a new vase.

W. H.P. S. Benjie's had a letter, and one twin fell down stairs.

-There is one sentence in the first paragraph of the following letter which reminds me of a very windy day, when I was staying at Summer Sweeting place.

In returning from a walk, by a short cut across the field, I met a boy who was running just about as fast as he could.

Soon after I came to another and much smaller boy, who was not running at all, but was sitting flat upon the ground, under a tree, and crying with might and main. This smaller boy proved to be Tommy. On a branch of the tree, just out of his reach, hung a broom, towards which his weeping eyes were turned in despair. A paper of peanuts which I happened to have soon quieted him, because, in order to crack them, he had to shut his mouth. At the first of it, however, he went on with his crying while picking out the meats, which so amused me that I was obliged to turn aside and laugh.

It appeared that Tommy had been riding horseback on his mother's broom "to see Billy," and when he had made believe get there, he wanted to hitch his horse. A larger boy, out of mischief, or rather in mischief, bent down a branch of the tree, telling Tommy there was a tiptop thing to tie up to. He helped Tommy to tie the horse to the branch, and then ran off across the field. It is very plain what happened when the branch sprang back to its place.

I unhitched the animal, and then Tommy and I mounted it, he behind me, and away we cantered to the house, my amazing gallops causing the little chap to laugh as loudly as he had cried.

-My dear Grandmother, —

Please to tell my sister I am much obliged to her for picking up that old iron for me. But that old rusty fire-shovel handle, I guess that will not do to put in again. For my father said, the last time, that he had bought that old fire-shovel handle half a dozen times. But Aunt Phebe's Tommy, he pulls it out again to ride horseback on.

I know a little girl just about as big as my sister, named Rosy. Maybe that is not her name. Maybe it is, because her face is so rosy. She had a lamb. And she's lost it. It ate out of her hand, and it followed her. It was a pet lamb. But it's lost. Gapper came up to inquire about it. Mr. Augustus wrote a notice and nailed it on to the Liberty Pole, and then Dorry chalked out a white lamb on black pasteboard, and painted a blue ribbon around its neck, and hung that up there too.

Gapper let Bubby Short and me have his donkey-cart to go to ride in. He kicked up when we licked him, and broke something. But a man came by and mended it. So we didn't get back till after dark. But the master didn't say anything after we told the reason why. Did you ever see a ghost? Do you believe they can whistle? I'll tell you what I ask such a question for.

There is an old house, and part of it is torn down, and nobody lives in it. It is built close to where the woods begin. The boys say there is a ghost in it. I'll tell you why. They say that if anybody goes by there whistling, something inside of that house whistles the same tune. Dorry says it's a jolly old ghost. Mr. Augustus thinks 'tis all very silly. Now I'll tell you something.

The night Bubby Short and I were coming back from taking a ride in Gapper's donkey-cart, we tried it. We didn't dare to lick him again, for fear he would kick up, so we rode just as slow! – and it was a lonesome road, but the moon was shining bright.

Says Bubby Short, "Do you believe that's the honeymoon?"

"No," says I. "That's what shines when a man is married to his wife."

"Are you scared of ghosts?" said Bubby Short.

"Can't tell till I see one," says I.

"How far off do you suppose they can see a fellow?" says he.

Says I, "I don't know. They can see best in the dark."

"Do you think they'd hurt a fellow?" says he.

"Maybe," says I. "There's the old house."