полная версия

полная версияButterflies and Moths (British)

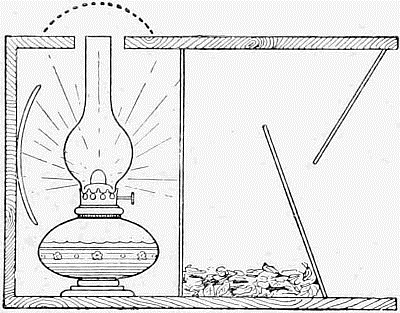

Fig. 51. – A Trap for Catching Moths.

Occasionally it happens that an entomologist is lucky enough to claim the friendship of a person who, from the nature of his calling, is peculiarly well qualified to render him great assistance. Thus a friendly lamplighter, expert and patient in the use of the cyanide bottle or pill box, is capable of giving valuable aid at times; and the keeper of a lighthouse has it in his power to capture many a gem that is seldom seen on the wing; but, although much may be done by means of these and other stationary lights, this kind of work does not compare favourably with the night rambles of a naturalist in the very haunts of the objects of his search.

For such out-door work in search of moths a good lantern is essential. An ordinary 'bull's-eye' is almost useless, for, although it concentrates a good light on certain objects, the narrow range of its rays constitutes a strong objection to its use for entomological work. For this purpose it is necessary that the rays of light not only pass in front of you, but also shoot off right and left to warn you of the approach of a moth before it is too late to wield the net. This wide range may be obtained by means of three flat glass sides, or, better still, by a bent plate glass front.

In addition to this you must go out provided with your net, killing bottle, and a number of pill boxes. Choose your night according to the hints already given, and if you are on the look-out for any particular species, be careful that the date of your outing is well timed, making any necessary allowances for the forwardness or backwardness of the season, for a moth that is generally due on a certain average time of the year may appear some weeks sooner if the preceding weeks have been unusually warm, or its emergence may be delayed considerably by the prevalence of cold east winds or a late frost.

Make up your mind as to the field of your operations before you start, and if possible choose a route that will carry you through a variety of situations, so that you may pass the favourite haunts of a number of different species. Clearings in woods with an abundant undergrowth, waste places with plenty of tall and rank vegetation, overgrown railway banks, clover fields, the flowery borders of corn fields, plantations in parks, heaths and moors, sheltered and overgrown hollows such as chalk pits and old disused quarries, reed and marsh land, all these are good localities, each one inhabited by its own peculiar species, and if your route runs through a fair variety of such places you may, other things being equally favourable, depend on a good catch.

See that your time also is well chosen. Of course you cannot say exactly what the night will be till it actually comes, and, as you have to start off before it is dark, you must consider the probabilities of the future from the present condition of the air. Let it be a night when a bright moon is not due, and if it follow a warm and moist day with a south or south-west wind, or if drizzly, so much the better; but let your feet be shod with boots that will permit you to wade through moist herbage without danger, and take a waterproof if necessary.

It is always advisable to be on your hunting ground before twilight sets in, as a number of moths venture out before the sun has disappeared; and then you can work on till midnight if you feel inclined, or even extend your labours till the early hours of the morning.

Before dusk you will meet with many of the little Tortrices (page 298) in sheltered spots, and a little later the Geometræ and Hawks will be on the wing. Thus, before dark, you may make good use of your net, dealing with your captures just in the same way as recommended in the case of butterflies.

After a time, however, the lantern will have to be brought to your assistance in making known the whereabouts of the later species, consisting chiefly of the Noctuæ, many of which do not make their appearance till it is quite dark. If now you carry your lantern in your left hand, your work will be rendered somewhat difficult and tedious, for, although one hand is sufficient to manage the net properly, you are compelled to rest your light on the ground every time you make a capture, as it is impossible to box your specimens unless both hands are quite free. This difficulty is easily overcome by suspending the lantern by means of a string or strap placed round your neck, allowing it to hang on your chest; and a further advantage is gained by having a second strap round your chest to prevent it from swaying about with every movement of your body. This arrangement gives you both hands perfectly free during the whole time, and also prevents the necessity of continually bringing yourself into a stooping or kneeling posture while you are examining or boxing the specimens you have netted.

There are now two courses open to you. Either you can kill and pin the moths as you catch them, fixing each one securely in the collecting box, or you may simply shut each one in a separate pill box and leave the remainder of the work to be done at home. If the ordinary collecting box only is used, a little of your time is necessarily occupied in pinning and transferring, and if many insects are about such an occupation may appear to you to be a waste of valuable time. But this is not all. Often and often will you find that while thus engaged a splendid moth will come and flutter round your light; and, before you have time to drop your collecting box and pick up the net, the fine creature you would have prized has darted off again. This certainly seems to speak in favour of the pill-boxing method, but it must be remembered that a few of the moths will continue to flutter after they have been boxed, so that when you arrive home they are more or less damaged, a large number of the scales that once adorned the wings now lying on the sides and bottom of the boxes. Perhaps the best plan is to take both the collecting box and also a quantity of pill boxes, and a little experience will soon show you which is the better accommodation for certain kinds.

Particular attention must be paid to flowers, some of which are very attractive to the Noctuæ especially. Sallow blossom in spring and ivy bloom in autumn should be carefully and frequently watched, and at other times the blossoms of heather, ragwort, bramble, clover, and various other flowers must be searched.

As you cast the rays of the lantern on the feasting moths some will prove themselves very wary, and dart away at your approach; but others will take but little notice of your advance, and will continue to suck the sweet nectar, their eyes glaring like living sparks.

As a rule the Noctuæ thus engaged are easily pill-boxed or caught direct in the cyanide bottle; but a few of the more restless species are to be made sure of only by a sweep of the net. Some will feign death as soon as disturbed, and allow themselves to drop among the foliage, where further search is generally fruitless.

Another common difficulty arises from the inconvenient height of many of the attractive blossoms – often so great that it is impossible to reach them with the net, and very difficult to direct the rays of your lantern on them. This is particularly the case with sallow and ivy, the flowers of which are two rich sources of supply to the entomologist.

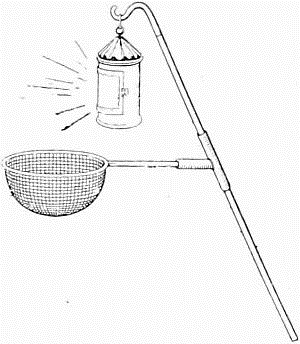

Fig. 52.

Fig. 53. – Net and Lantern for Taking Moths from High Blossoms.

Those who intend giving special attention to these blossoms should be provided with some form of apparatus that will enable them to extend their operations as high as possible. Perhaps the most effective arrangement is the well-known combination here figured. It consists of a long and stout stick, at the top of which is a tubular joint (fig. 52) that might be termed a T-piece were it not that the smaller part does not stand out at right angles to the other. In this is fixed, in a straight line with the stick, a short rod on which hangs a lantern – an ordinary bull's-eye answers well here; and in the smaller tube is another short rod carrying a shallow basin-shaped net, and of such a length that the net is just in advance of the lantern.

At first sight this arrangement will strike you as being very unsatisfactory, there being no kind of trap to prevent the escape of the insects. But it must be remembered that moths are more or less addicted to habits of intemperance – that they will hold on to the supply of the sweet fluid they enjoy till they are ready to drop with intoxication. This being the case, some will fall into your net as soon as they are startled by the sudden and near approach of the glare of your lamp, and others are easily made to fall therein by gently tapping the flower-bearing stems from below with the edge of the ring.

Having become acquainted with this very sad propensity, which thus brings ruin to so many unfortunate moths, can we not yet further turn their evil doings to our own profit in our endeavours to become acquainted with their structure and history? Most certainly we can. All we have to do is to distribute in their haunts a bountiful supply of some artificial intoxicant such as they love, and then lie in wait for the victims that fall a prey to our snare. This process is known to entomologists as 'sugaring,' and is a splendid means of securing an abundance of species, often including some rare ones that are scarcely to be obtained by any other plan. Let us now inquire into the modus operandi of this interesting operation.

The first thing to do is to prepare the luring sweetmeat. Supply yourself with a quantity of strong, dark treacle, and also some dark brown sugar; always remembering, in the selection of these viands, that odour rather than purity is to be the guide. The best kinds of sugar are those very dark and moist brands imported in a raw state from the West Indies, nothing being better than that known as 'Jamaica Foots.'

Mix about equal quantities of these with a little stale beer, and boil and stir till all the sugar is dissolved. The consistency of the mixture should be such that it will work well with a brush when used as a paint – not too thick, nor so thin that it is easily absorbed by the substance on which it is 'painted,' nor must it be in such a fluid condition that it easily runs.

When satisfied on these points, transfer the mixture to a tin canister, see it properly covered, and set it aside as your 'stock' from which you can draw supplies as required. Now secure an ordinary painter's brush of convenient size, and a number of strips of linen or other rag, each one of which is fastened to a hook formed of bent wire. These items, together with the usual lantern, collecting box, pill boxes, and killing bottle, complete your outfit for the sugaring expedition.

When the selected time for operations has arrived, take sufficient 'sugar' for your night's work, mix it well with sufficient strong rum to give it a very decided odour, and start off at dusk with this and the other requisites just mentioned.

The night chosen should be warm and calm, with a rather damp atmosphere, and no moon preferred. Let your locality be a well-wooded one; abounding, if possible, with giant oaks and other trees, and containing open spaces with plenty of underwood and rank herbage. Such localities are to be met with at their best in forest lands, and if you would do wonders at sugaring you cannot do better than arrange for spending your holidays in such a spot as the New Forest, taking with you sufficient 'sugar' for several nights' work.

Having reached a likely spot of no very great extent, you prepare for real work. Light up the lamp, and get out your sugaring tin and brush ready for action. Take your course along some definite track that you are sure to remember, painting vertical strips of sugar, about a foot long, on the trunks of trees or on palings, and hanging strips of rag that have just been steeped in the sugar on the branches of small trees and shrubs where you do not find good surfaces for the brush.

After satisfying yourself concerning the amount of sugar distributed, retrace your steps, examining every patch of sugar as you go. It will not be long before signs of life appear. Earwigs, spiders, centipedes and slugs will soon search out the luscious feast, but unless the time and the locality are ill chosen, the lantern will soon reveal a goodly number of moths, with eyes glaring like little balls of fire, greedily devouring the bounteous repast. These will consist chiefly of Noctuæ, but Sphinges, Geometræ and numerous small species also join the company.

Some will exhibit a restless disposition, either darting off before you make a close approach, or keeping their wings in rapid vibration as if to be fully prepared for a hasty retreat when occasion demands. These must receive your attention first; and, having secured them, proceed to box as many as you require of the more lazy and gluttonous species.

As a rule, moths thus engaged are easily pill-boxed, but the livelier ones will not submit to such treatment without attempting to escape. The best way to secure these is either to cover them with the opened cyanide bottle (or its substitute), and replace the cork as soon as a favourable opportunity occurs; or to perform the same feat with a glass-bottomed pill box.

The advantage of the latter over the ordinary boxes will be seen at once. After the insect is covered, its movements can be watched, and so a favourable opportunity can be seized for snapping on the lid.

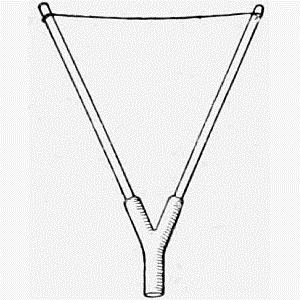

As already stated, some moths feign death when in danger, allowing themselves to fall in places where they are often quite safe from capture. Others allow themselves to fall simply because they have so gorged themselves with the intoxicating sweet that they can no longer maintain their hold. Both these classes of sugar seekers may easily be secured by means of a net commonly known as the 'sugaring net.'

Fig. 54. – Frame for the Sugaring Net.

This implement is so simple in its construction that anyone can easily make his own. The frame may consist of two straight wires or canes fixed in a metal Y, and the other ends joined by a piece of strong string or catgut as shown in fig. 54. The net itself need not be deep. As soon as you reach a tree where moths are feeding on the sugar, press the string of the net against the bark just below them. The string at once assumes the form of the trunk so well that you may be sure of every insect that falls while you are boxing.

For this work both hands must be free, and this is easily managed in spite of the number of appliances called into service. The lantern is slung round your neck and secured by a strap round the chest. The 'sugaring net' has a very short stick, and just while you are engaged in boxing specimens, it may be gently held against the trunk by a slight pressure of the body. But such precautions as these are necessary only when the night worker is out alone. There are many circumstances, however, that render the work of two or more in company much more enjoyable than that of a single-handed entomologist. The labours are considerably expedited where a division enables each one of the night ramblers to take a particular portion of the work; and if there is such a person as a nervous entomologist, that individual should on no account go a sugaring in lonely spots on dark nights. Every rustling leaf gives such a one a start; all footsteps are those of approaching disturbers of the peace; and when at last the invisible landowner or his keeper, attracted by the mysterious movements of the lamp, greets him with his gruff 'What's your business here?' then for the moment he forgets his enchanting hobby and wishes he were safely at home.

It is certainly advisable to take a friend, whether an entomologist or not, on such expeditions; and if you intend working on private grounds, always make previous arrangements with the property owner, that you may fear no foes and dread no surprises; for a sugarer is far more sure of success in his work if he keeps a cool head and has nothing to think about for the time being but his moths and his boxes.

A few hours at this interesting employment pass away very rapidly, and when midnight arrives there is often no great desire to leave off, especially when it is known that some species of moths are not very busy till very late at night. Still it is not advisable to surfeit oneself with even the sweets of life. Perhaps it is better as a rule to work the early species only on one night, and reserve another for the later ones. The searchings are then always carried on with vigour throughout, and the labours that are thus never made laborious ever retain their attractiveness in the future.

It has often been observed that, when sugaring has been carried on for a few successive nights in the same locality, the success is greater each night than on the one preceding it. Hence it is a common practice to work a chosen 'run' for two, three, or more nights in succession; and some collectors even go so far as to lay on the bait for a night or two previous to starting work. For the same reason it is often advisable to continue the use of a fairly productive beat rather than to wander in search of a new one.

In the neighbourhood of large towns one may often meet with patches of sugared bark that mark the course and extent of a brother entomologist's beat, and such are valuable to an inexperienced amateur in that they give him some idea of the nature of the localities that are chosen by more expert collectors. But it must be remembered that each entomologist has a moral right to a run he has baited, and that it is considered ungentlemanly, if not unjust, to take insects from sugar laid by another. I have sometimes seen cards, bearing the names of the collectors and the date of working, tacked on to baited trees and fences, thus establishing their temporary exclusive rights to the use of their runs. Such precautions are not necessary in large tracts of forest land, where the choice of runs is practically unlimited.

There are two other modes of capture available to the moth collector – the use of decoy females, and the employment of 'sugar traps' – and both these may be used on the sugaring run, or at other times either in the woods or in your own garden.

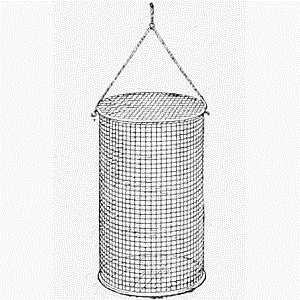

Fig. 55. – Cage for Decoy Females.

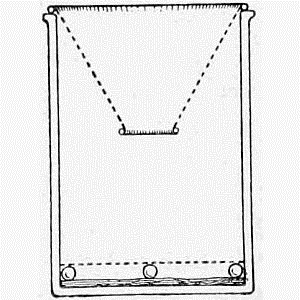

Fig. 56. – A Sugar Trap.

The wonderful acuteness of the sense by which the males of certain species are enabled to seek out the females has already been alluded to, and the possession of a suitable decoy will often bring you a number of beautiful admirers without the least trouble, except that taken in securing the decoy and preparing her temporary abode. It is absolutely necessary that the female moth be one that has recently emerged, and consequently you had better secure her in one of her earlier stages, either by previous rearing or by collecting the pupæ.

A little cage composed of a framework of wire covered with gauze must now be made. Perhaps the simplest pattern is that illustrated. Here the gauze is attached to two wire rings, only a few inches in diameter, and suspended by a string. Such a cage answers every purpose in the field, and has the advantage of folding into an exceedingly small space when not in use. It may be suspended in your garden or taken into the field whenever you have a suitable decoy at your disposal.

The sugar trap may be of much the same pattern as that in which a light is used, but if intended for field work it should be of a convenient size for portability. A lighter and far more convenient form may be constructed as follows:

Procure a large cylindrical tin box, and cut a circular piece of perforated zinc just small enough to drop into it. Then make two wire rings, one a little larger than the top of the tin, and the other only about an inch in diameter. Next make a conical net of leno, open at both ends, and of such a size that the two rings may form the frames of its two extremities. When the trap is required for use, cut a circular piece of flannel or other absorbent, steep it in sugar that has just been flavoured with rum, and place it in the bottom of the tin. Then place a few pebbles of equal size around the sides to support the zinc partition, drop in the partition, and then allow the net to hang on the rim as shown in the sketch.

This arrangement will explain itself. The moths, attracted by the sweet perfume, flutter about in the net till at last they find their way through the small ring. Once in, they make further attempts to reach the sugar; and, at last, finding all efforts fruitless, and, like Paddy at the fair, not being able to discover the 'entrance out,' they finally settle down in a disappointed mood awaiting your pleasure.

Perhaps another word of explanation is necessary here. Why not allow the poor creatures to reach the sugar that attracted them to the spot? The reason is this. They sometimes gorge themselves to such an extent that their bodies, dilated to the fullest capacity with syrup, are a bit troublesome when the insects are placed in the cabinet. It is therefore advisable to see that the zinc is so far above the sugar that the moths are unable to reach the latter by thrusting their extended proboscides through the perforations. A few dead leaves scattered on the zinc is also a useful addition, since it affords shelter to such of the insects as prefer it.

This is a very useful trap to keep in one's garden throughout the season. It may not attract large numbers, but it has the advantage that it requires no watching. It is simply necessary to set it at dusk, and remove the captives in the morning or at your leisure.

CHAPTER VII

COLLECTING OVA, LARVÆ, AND PUPÆ

We have already observed that insects should, as a rule, be set as soon as possible after their capture; and it would therefore seem that this is the proper place for instructions in this part of the work. But it so happens that butterflies and moths are to be obtained by means other than those already described, and we shall therefore consider these previous to the study of the various processes connected with the setting and preserving of our specimens.

Were we to confine our attention to the capture of the perfect forms only, our knowledge of the Lepidoptera would be scanty indeed, for we should then be ignorant of the earlier stages of the creatures' lives, and have no opportunity of witnessing the wonderful transformations through which they have to pass.

Such an imperfect acquaintance with butterflies and moths will, I hope, not satisfy the readers of these pages; so it is intended, in the next two chapters, to give a little assistance to those who would like to know how to set to work at the collection of their eggs and larvæ, how to search for the pupæ, and how to rear the insects from the stage at which they are acquired till they finally emerge in the perfect form.

These portions of an entomologist's work certainly take up a great deal of his time, and also require much patience and perseverance; but the advantages derived cannot be over-estimated, for in addition to the knowledge gained of the early stages of insect life, this kind of work will enable him to place in his cabinet a number of gems he would otherwise have not and probably know not. Occasionally a prize may be obtained in the form of a cluster of eggs (ova) of a rare species, in many instances the larvæ are to be obtained with comparative ease, while the perfect insects of the same species are not often seen or not easily captured, and many a rare pupa has been dug out of its hiding place during a season when the entomologist had but little other work to occupy his time.