полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

The story of Baucis and Philemon has been imitated by Swift in a burlesque style, the actors in the change being two wandering saints, and the house being changed into a church, of which Philemon is made the parson:

… They scarce had spoke, when, fair and soft,The roof began to mount aloft;Aloft rose every beam and rafter;The heavy wall climbed slowly after.The chimney widened and grew higher,Became a steeple with a spire.The kettle to the top was hoist,And there stood fastened to a joist,But with the upside down, to showIts inclination for below;In vain, for a superior force,Applied at bottom, stops its course;Doomed ever in suspense to dwell,'Tis now no kettle, but a bell.A wooden jack, which had almostLost by disuse the art to roast,A sudden alteration feels,Increased by new intestine wheels;And, what exalts the wonder more,The number made the motion slower;The flier, though 't had leaden feet,Turned round so quick you scarce could see 't;But slackened by some secret power,Now hardly moves an inch an hour.The jack and chimney, near allied,Had never left each other's side.The chimney to a steeple grown,The jack would not be left alone;But up against the steeple reared,Became a clock, and still adhered;And still its love to household caresBy a shrill voice at noon declares,Warning the cook-maid not to burnThat roast meat which it cannot turn.The groaning chair began to crawl,Like a huge snail, along the wall;There stuck aloft in public view,And with small change, a pulpit grew.A bedstead of the antique mode,Compact of timber many a load,Such as our ancestors did use,Was metamorphosed into pews,Which still their ancient nature keepBy lodging folks disposed to sleep.64. Juno's Best Gift. What the queen of heaven deemed the greatest blessing reserved for mortals is narrated in the beautiful myth of Biton and Cleobis. One Cydippe, an ancient priestess of the white-armed goddess, had desired to behold the famous new statue of Hera at Argos. Her sons testified their affection for their mother by yoking themselves, since no oxen were at hand, to her chariot, and so dragging her through heat and dust many a weary league till they reached the temple, where stood the gold and ivory masterwork of Polyclitus. With admiration the devoted priestess and her pious sons were received by the populace crowding round the statue. The priest officiating in the solemn rites thought meet that so reverend a worshiper should herself approach the goddess, – ay, should ask of Hera some blessing on her faithful sons:

… Slowly old Cydippe rose and cried:"Hera, whose priestess I have been and am,Virgin and matron, at whose angry eyesZeus trembles, and the windless plain of heavenWith hyperborean echoes rings and roars,Remembering thy dread nuptials, a wise god,Golden and white in thy new-carven shape,Hear me! and grant for these my pious sons,Who saw my tears, and wound their tender armsAround me, and kissed me calm, and since no steerStayed in the byre, dragged out the chariot old,And wore themselves the galling yoke, and broughtTheir mother to the feast of her desire,Grant them, O Hera, thy best gift of gifts!"Whereat the statue from its jeweled eyesLightened, and thunder ran from cloud to cloudIn heaven, and the vast company was hushed.But when they sought for Cleobis, behold,He lay there still, and by his brother's sideLay Biton, smiling through ambrosial curls,And when the people touched them they were dead.7865. Myths of Minerva. Minerva, as we have seen,79 presided over the useful and ornamental arts, both those of men – such as agriculture and navigation – and those of women – spinning, weaving, and needlework. She was also a warlike divinity, but favored only defensive warfare. With Mars' savage love of violence and bloodshed she, therefore, had no sympathy. Athens, her chosen seat, her own city, was awarded to her as the prize of a peaceful contest with Neptune, who also aspired to it. In the reign of Cecrops, the first king of Athens, the two deities had contended for the possession of the city. The gods decreed that it should be awarded to the one who produced the gift most useful to mortals. Neptune gave the horse; Minerva produced the olive. The gods awarded the city to the goddess, and after her Greek appellation, Athena, it was named.

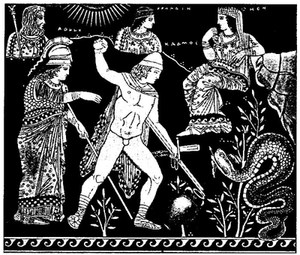

66. Arachne. In another contest, a mortal dared to come into competition with the gray-eyed daughter of Jove. This was Arachne, a maiden who had attained such skill in the arts of carding and spinning, of weaving and embroidery, that the Nymphs themselves would leave their groves and fountains to come and gaze upon her work. It was not only beautiful when it was done, but beautiful also in the doing. To watch her one would have said that Minerva herself had taught her. But this she denied, and could not bear to be thought a pupil even of a goddess. "Let Minerva try her skill with mine," said she. "If beaten, I will pay the penalty." Minerva heard this and was displeased. Assuming the form of an old woman, she appeared to Arachne and kindly advised her to challenge her fellow mortals if she would, but at once to ask forgiveness of the goddess. Arachne bade the old dame to keep her counsel for others. "I am not afraid of the goddess; let her try her skill, if she dare venture." "She comes," said Minerva, and dropping her disguise, stood confessed. The Nymphs bent low in homage and all the bystanders paid reverence. Arachne alone was unterrified. A sudden color dyed her cheek, and then she grew pale; but she stood to her resolve and rushed on her fate. They proceed to the contest. Each takes her station and attaches the web to the beam. Then the slender shuttle is passed in and out among the threads. The reed with its fine teeth strikes up the woof into its place and compacts the web. Wool of Tyrian dye is contrasted with that of other colors, shaded off into one another so adroitly that the joining deceives the eye. And the effect is like the bow whose long arch tinges the heavens, formed by sunbeams reflected from the shower,80 in which, where the colors meet they seem as one, but at a little distance from the point of contact are wholly different.

Minerva wove the scene of her contest with Neptune (Poseidon). Twelve of the heavenly powers were represented, Jupiter, with august gravity, sitting in the midst. Neptune, the ruler of the sea, held his trident and appeared to have just smitten the earth, from which a horse had leaped forth. The bright-eyed goddess depicted herself with helmed head, her ægis covering her breast, as when she had created the olive tree with its berries and its dark green leaves.

Fig. 52. Contest of Athena and Poseidon

Amongst these leaves she made a Butterfly,With excellent device and wondrous slight,Fluttering among the olives wantonly,That seemed to live, so like it was in sight;The velvet nap which on his wings doth lie,The silken down with which his back is dight,His broad outstretchèd horns, his hairy thighs,His glorious colors, and his glistering eyes.Which when Arachne saw, as overlaidAnd masterèd with workmanship so rare,She stood astonished long, ne aught gainsaid;And with fast-fixèd eyes on her did stare.81

So wonderful was the central circle of Minerva's web; and in the four corners were represented incidents illustrating the displeasure of the gods at such presumptuous mortals as had dared to contend with them. These were meant as warnings from Minerva to her rival to give up the contest before it was too late.

But Arachne did not yield. She filled her web with subjects designedly chosen to exhibit the failings and errors of the gods. One scene represented Leda caressing the swan; and another, Danaë and the golden shower. Still another depicted Europa deceived by Jupiter under the disguise of a bull. Its appearance was that of a real bull, so naturally was it wrought and so natural the water in which it swam.

With such subjects Arachne filled her canvas, wonderfully well done but strongly marking her presumption and impiety. Minerva could not forbear to admire, yet was indignant at the insult. She struck the web with her shuttle and rent it in pieces; then, touching the forehead of Arachne, she made her realize her guilt. It was more than mortal could bear; and forthwith Arachne hanged herself. "Live, guilty woman," said Minerva, "but that thou mayest preserve the memory of this lesson continue to hang, both thou and thy descendants, to all future times." Then, sprinkling her with the juices of aconite, the goddess transformed her into a spider, forever spinning the thread by which she is suspended.82

67. Myths of Mars. The relations of Mars to other deities may be best illustrated by passages from the Iliad, which, generally speaking, presents him in no very favorable light.

68. Mars and Diomede. In the war of the Greeks and the Trojans,83 the cause of the former was espoused by Minerva, of the latter by Mars. Among the chieftains of the Greeks in a certain battle, Diomede, son of Tydeus, was prominent. Now when Mars, scourge of mortals, beheld noble Diomede, he made straight at him.

… And when they were come nigh in onset on one another, first Mars thrust over the yoke and horses' reins with spear of bronze, eager to take away his life. But the bright-eyed goddess Minerva with her hand seized the spear and thrust it up over the car, to spend itself in vain. Next Diomede of the loud war cry attacked with spear of bronze; and Minerva drave it home against Mars' nethermost belly, where his taslets were girt about him. There smote he him and wounded him, rending through his fair skin, – and plucked forth the spear again. Then brazen Mars bellowed loud as nine thousand warriors or ten thousand cry in battle as they join in strife and fray. Thereat trembling gat hold of Achæans and Trojans for fear, so mightily bellowed Mars insatiate of battle.

FIG. 53. ATHENA

Even as gloomy mist appeareth from the clouds when after heat a stormy wind ariseth, even so to Tydeus' son Diomede brazen Mars appeared amid clouds, faring to wide Heaven. Swiftly came he to the gods' dwelling, steep Olympus, and sat beside Jupiter, son of Cronus, with grief at heart, and showed the immortal blood flowing from the wound, and piteously spake to him winged words: "Father Jupiter, hast thou no indignation to behold these violent deeds? For ever cruelly suffer we gods by one another's devices, in showing men grace. With thee are we all at variance, because thou didst beget that reckless maiden and baleful, whose thought is ever of iniquitous deeds. For all the other gods that are in Olympus hearken to thee, and we are subject every one; only her thou chaste-nest not, neither in deed nor word, but settest her on, because this pestilent one is thine own offspring. Now hath she urged on Tydeus' son, even overweening Diomede, to rage furiously against the immortal gods. The Cyprian first he wounded in close fight, in the wrist of her hand, and then assailed he me, even me, with the might of a god. Howbeit my swift feet bare me away; else had I long endured anguish there amid the grisly heaps of dead, or else had lived strengthless from the smitings of the spear."

Then Jupiter the cloud-gatherer looked sternly at him, and said: "Nay, thou renegade, sit not by me and whine. Most hateful to me art thou of all gods that dwell in Olympus; thou ever lovest strife and wars and battles. Truly thy mother's spirit is intolerable, unyielding, even Juno's; her can I scarce rule with words. Therefore I deem that by her prompting thou art in this plight. Yet will I no longer endure to see thee in anguish; mine offspring art thou, and to me thy mother bare thee. But wert thou born of any other god unto this violence, long ere this hadst thou been lower than the sons of Heaven."

So spake he and bade Pæan heal him. And Pæan laid assuaging drugs upon the wound, and healed him, seeing he was in no wise of mortal mold. Even as fig juice maketh haste to thicken white milk, that is liquid but curdleth speedily as a man stirreth, even so swiftly healed he impetuous Mars. And Hebe bathed him and clothed him in gracious raiment, and he sate down by Jupiter, son of Cronus, glorying in his might.

Then fared the twain back to the mansion of great Jupiter, even Juno and Minerva, having stayed Mars, scourge of mortals, from his man-slaying.84

69. Mars and Minerva. It would seem that the insatiate son of Juno should have learned by this sad experience to avoid measuring arms with the ægis-bearing Minerva. But he renewed the contest at a later period in the fortunes of the Trojan War:

… Jupiter knew what was coming as he sat upon Olympus, and his heart within him laughed pleasantly when he beheld that strife of gods. Then no longer stood they asunder, for Mars, piercer of shields, began the battle and first made for Minerva with his bronze spear, and spake a taunting word: "Wherefore, O dogfly, dost thou match gods with gods in strife, with stormy daring, as thy great spirit moveth thee? Rememberest thou not how thou movedst Diomede, Tydeus' son, to wound me, and thyself didst take a visible spear and thrust it straight at me and pierce through my fair skin? Therefore deem I now that thou shalt pay me for all that thou hast done."

Thus saying, he smote on the dread tasseled ægis that not even the lightning of Jupiter can overcome – thereon smote blood-stained Mars with his long spear. But she, giving back, grasped with stout hand a stone that lay upon the plain, black, rugged, huge, which men of old time set to be the landmark of a field; this hurled she, and smote impetuous Mars on the neck, and unstrung his limbs. Seven roods he covered in his fall, and soiled his hair with dust, and his armor rang upon him. And Minerva laughed, and spake to him winged words exultingly: "Fool, not even yet hast thou learnt how far better than thou I claim to be, that thus thou matchest thy might with mine. Thus shalt thou satisfy thy mother's curses, who deviseth mischief against thee in her wrath, for that thou hast left the Achæans and givest the proud Trojans aid."

Thus having said, she turned from him her shining eyes. Him did Venus, daughter of Jupiter, take by the hand and lead away, groaning continually, for scarce gathered he his spirit back to him.85

70. The Fortunes of Cadmus. Toward mortals Mars could show himself, on occasion, as vindictive as his fair foe, the unwearied daughter of Jove. This fact not only Cadmus, who slew a serpent sacred to Mars, but all the family of Cadmus found out to their cost.

Fig. 54. Cadmus slaying the Dragon

When Europa was carried away by Jupiter in the guise of a bull, her father Agenor commanded his son Cadmus to go in search of her and not to return without her. Cadmus sought long and far; then, not daring to return unsuccessful, consulted the oracle of Apollo to know what country he should settle in. The oracle informed him that he would find a cow in the field, should follow her wherever she might wander, and where she stopped should build a city and call it Thebes. Cadmus had hardly left the Castalian cave, from which the oracle was delivered, when he saw a young cow slowly walking before him. He followed her close, offering at the same time his prayers to Phœbus. The cow went on till she passed the shallow channel of Cephissus and came out into the plain of Panope. There she stood still. Cadmus gave thanks, and stooping down kissed the foreign soil, then lifting his eyes, greeted the surrounding mountains. Wishing to offer a sacrifice to his protecting deity, Minerva, he sent his servants to seek pure water for a libation. Near by there stood an ancient grove which had never been profaned by the ax, in the midst of which was a cave thick covered with the growth of bushes, its roof forming a low arch from beneath which burst forth a fountain of purest water. But in the cave lurked a serpent with crested head, and scales glittering like gold; his eyes shone like fire; his body was swollen with venom; he vibrated a triple tongue and showed a triple row of teeth. No sooner had the Tyrians dipped their pitchers in the fountain and the in-gushing waters had made a sound, than the monster, twisting his scaly body in a huge coil, darted upon them and destroyed some with his fangs, others in his folds, and others with his poisonous breath.

Cadmus, having waited for the return of his men till midday, went in search of them. When he entered the wood and saw their lifeless bodies and the dragon with his bloody jaws, not knowing that the serpent was sacred to Mars, scourge of mortals, he lifted a huge stone and threw it with all his force at the monster. The blow made no impression. Minerva, however, was present, unseen, to aid her worshiper. Cadmus next threw his javelin, which penetrated the serpent's scales and pierced through to his entrails. The monster attempted to draw out the weapon with his mouth, but broke it off, leaving the iron point rankling in his flesh. His neck swelled with rage, bloody foam covered his jaws, and the breath of his nostrils poisoned the air around. As he moved onward, Cadmus retreated before him, holding his spear opposite to the serpent's opened jaws. At last, watching his chance, the hero thrust the spear at a moment when the animal's head thrown back came against the trunk of a tree, and so succeeded in pinning him to its side.

While Cadmus stood over his conquered foe, contemplating its vast size, a voice was heard (from whence he knew not, but it was Minerva's) commanding him to take the dragon's teeth and sow them in the earth. Scarce had he done so when the clods began to move and the points of spears to appear above the surface. Next, helmets with their nodding plumes came up; next, the shoulders and breasts and limbs of men with weapons, and in time a harvest of armed warriors. Cadmus prepared to encounter a new enemy, but one of them said to him, "Meddle not with our civil war." With that he who had spoken smote one of his earthborn brothers with a sword, and he himself fell pierced with an arrow from another. The latter fell victim to a fourth, and in like manner the whole crowd dealt with each other till all but five fell slain. These five joined with Cadmus in building his city, to which they gave the name appointed.

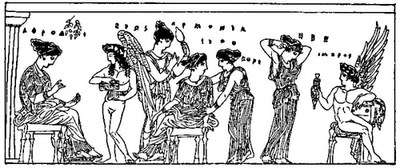

FIG. 55. Harmonia in Company of Deities

As penance for the destruction of this sacred serpent, Cadmus served Mars for a period of eight years. After he had been absolved of his impiety, Minerva set him over the realm of Thebes, and Jove gave him to wife Harmonia, the daughter of Venus and Mars. The gods left Olympus to honor the occasion with their presence; and Vulcan presented the bride with a necklace of surpassing brilliancy, his own workmanship. Of this marriage were born four daughters, Semele, Ino, Autonoë, and Agave, and one son, Polydorus. But in spite of the atonement made by Cadmus, a fatality hung over the family. The very necklace of Vulcan seemed to catch the spirit of ill luck and convey a baleful influence to such as wore it. Semele, Ino, Actæon the son of Autonoë, and Pentheus the son of Agave, all perished by violence. Cadmus and Harmonia quitted Thebes, grown odious to them, and emigrated to the country of the Enchelians, who received them with honor and made Cadmus their king. But the misfortunes of their children still weighing upon their minds, Cadmus one day exclaimed, "If a serpent's life is so dear to the gods, I would I were myself a serpent." No sooner had he uttered the words than he began to change his form. Harmonia, beholding it, prayed the gods to let her share his fate. Both became serpents. It is said that, mindful of their origin, they neither avoid the presence of man nor do they injure any one. But the curse appears not to have passed from their house until the sons of their great-great-grandson Œdipus had by fraternal strife ended themselves and the family.86

Fig. 56. The Forge of Vulcan

From the painting by Velasquez

71. Myths of Vulcan. The stories of Vulcan are few, although incidents illustrating his character are sufficiently numerous. According to an account already given, Vulcan, because of his lameness, was cast out of Heaven by his mother Juno. The sea-goddesses Eurynome and Thetis took him mercifully to themselves, and for nine years cared for him, while he plied his trade and gained proficiency in it. In order to revenge himself upon the mother who had so despitefully used him, he fashioned in the depths of the sea a throne of cunning device, which he sent to his mother. She, gladly accepting the glorious gift, sat down upon it, to find out that straightway all manner of invisible chains and fetters wound and clasped themselves about her so that she could not rise. The assistance of the gods was of no avail to release her. Then Mars sought to bring Vulcan to Heaven by force that he might undo his trickery; but before the flames of the fire-god, the impetuous warrior speedily retreated. One god, however, the jovial Bacchus, was dear to the blacksmith. He drenched Vulcan with wine, conducted him to Olympus, and by persuasion caused him to set the queen of gods and men at liberty.

FIG. 57. A Sacrifice to Apollo

That Vulcan was not permanently hostile to Juno is shown by the services that on various occasions he rendered her. He forged the shield of her favorite Achilles; and, at her instance, he undertook a contest against the river Xanthus. Homer87 describes the burning of elms and willow trees and tamarisks, the parching of the plains, the bubbling of the waters, that signalized the fight, and how the eels and other fish were afflicted by Vulcan till Xanthus in anguish cried for quarter.

72. Myths of Apollo. The myths which cluster about the name of Phœbus Apollo illustrate, first, his birth and the wanderings of his mother, Latona; secondly, his victory over darkness and winter; thirdly, his gifts to man, – youth and vigor, the sunshine of spring, and the vegetation of early summer; fourthly, his baleful influence, – the sunstroke and drought of midsummer, the miasma of autumn; fifthly, his life on earth, as friend and counselor of mankind, – healer, soothsayer, and musician, prototype of manly beauty, and lover of beautiful women.

73. The Wanderings of Latona. Persecuted by the jealousy of the white-armed Juno, Latona fled from land to land. At last, bearing in her arms the infant progeny of Jove, she reached Lycia, weary with her burden and parched with thirst. There the following adventure ensued. By chance the persecuted goddess espied in the bottom of the valley a pond of clear water, where the country people were at work gathering willows and osiers. She approached and kneeling on the bank would have slaked her thirst in the cool stream, but the rustics forbade her. "Why do you refuse me water?" said she. "Water is free to all. Yet I ask it of you as a favor. I have no intention of washing my limbs in it, weary though they be, but only of quenching my thirst. A draft of water would be nectar to me, and I would own myself indebted to you for life itself. Let these infants move your pity, who stretch out their little arms as if to plead for me."

But the clowns persisted in their rudeness; they added jeers, and threatened violence if she did not leave the place. They waded into the pond and stirred up the mud with their feet, so as to make the water unfit to drink. Enraged, the goddess no longer supplicated the clowns, but lifting her hands to Heaven exclaimed, "May they never quit that pool but pass their lives there!" And it came to pass accordingly. They still live in the water, sometimes totally submerged, then raising their heads above the surface or swimming upon it; sometimes coming out upon the bank, but soon leaping back again into the water. Their voices are harsh, their throats bloated, their mouths distended by constant railing; their necks have shrunk up and disappeared, and their heads are joined to their bodies. Their backs are green, their disproportioned bellies white. They dwell as frogs in the slimy pool.88