полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

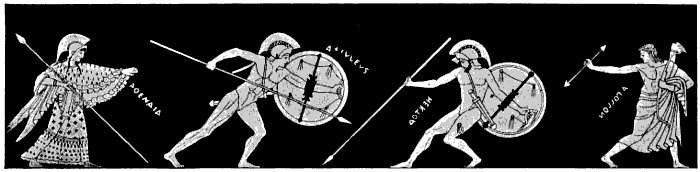

Then Achilles went forth to battle, heartened by the inspiration of Minerva and filled with a rage and thirst for vengeance that made him irresistible. As he mounted his chariot, one of his immortal coursers was, strange to say, endowed suddenly with speech from on high and, breaking into prophecy, warned the hero of his approaching doom. But, nothing daunted, Achilles pressed upon the foe. The bravest warriors fled before him or fell by his lance.304 Hector, cautioned by Apollo, kept aloof; but the god, assuming the form of one of Priam's sons, Lycaon, urged Æneas to encounter the terrible warrior. Æneas, though he felt himself unequal, did not decline the combat. He hurled his spear with all his force against the shield, the work of Vulcan. The spear pierced two plates of the shield, but was stopped in the third. Achilles threw his spear with better success. It pierced through the shield of Æneas, but glanced near his shoulder and made no wound. Then Æneas, seizing a stone, such as two men of modern times could hardly lift, was about to throw it, – and Achilles, with sword drawn, was about to rush upon him, – when Neptune, looking out upon the contest, had pity upon Æneas, who was sure to have the worst of it. The god, consequently, spread a cloud between the combatants and, lifting the Trojan from the ground, bore him over the heads of warriors and steeds to the rear of the battle. Achilles, when the mist cleared away, looked round in vain for his adversary, and acknowledging the prodigy, turned his arms against other champions. But none dared stand before him; and Priam from his city walls beheld the whole army in full flight toward the city. He gave command to open wide the gates to receive the fugitives, and to shut them as soon as the Trojans should have passed, lest the enemy should enter likewise. But Achilles was so close in pursuit that that would have been impossible if Apollo had not, in the form of Agenor, Priam's son, first encountered the swift-footed hero, then turned in flight, and taken the way apart from the city. Achilles pursued, and had chased his supposed victim far from the walls before the god disclosed himself.305

215. The Death of Hector. But when the rest had escaped into the town Hector stood without, determined to await the combat. His father called to him from the walls, begging him to retire nor tempt the encounter. His mother, Hecuba, also besought him, but all in vain. "How can I," said he to himself, "by whose command the people went to this day's contest where so many have fallen, seek refuge for myself from a single foe? Or shall I offer to yield up Helen and all her treasures and ample of our own beside? Ah no! even that is too late. He would not hear me through, but slay me while I spoke." While he thus ruminated, Achilles approached, terrible as Mars, his armor flashing lightning as he moved. At that sight Hector's heart failed him and he fled. Achilles swiftly pursued. They ran, still keeping near the walls, till they had thrice encircled the city. As often as Hector approached the walls Achilles intercepted him and forced him to keep out in a wider circle. But Apollo sustained Hector's strength and would not let him sink in weariness. Then Pallas, assuming the form of Deiphobus, Hector's bravest brother, appeared suddenly at his side. Hector saw him with delight, and thus strengthened, stopped his flight, and, turning to meet Achilles, threw his spear. It struck the shield of Achilles and bounded back. He turned to receive another from the hand of Deiphobus, but Deiphobus was gone. Then Hector understood his doom and said, "Alas! it is plain this is my hour to die! I thought Deiphobus at hand, but Pallas deceived me, and he is still in Troy. But I will not fall inglorious." So saying he drew his falchion from his side and rushed at once to combat. Achilles, secure behind his shield, waited the approach of Hector. When he came within reach of his spear, Achilles, choosing with his eye a vulnerable part where the armor leaves the neck uncovered, aimed his spear at that part, and Hector fell, death-wounded. Feebly he said, "Spare my body! Let my parents ransom it, and let me receive funeral rites from the sons and daughters of Troy." To which Achilles replied, "Dog, name not ransom nor pity to me, on whom you have brought such dire distress. No! trust me, nought shall save thy carcass from the dogs. Though twenty ransoms and thy weight in gold were offered, I should refuse it all."306

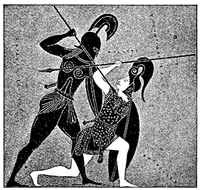

Fig. 159. Contest of Achilles and Hector

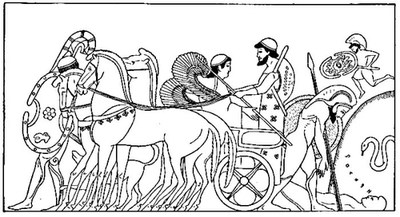

216. Achilles drags the Body of Hector. So saying, the son of Peleus stripped the body of its armor, and, fastening cords to the feet, tied them behind his chariot, leaving the body to trail along the ground. Then mounting the chariot he lashed the steeds and so dragged the body to and fro before the city. No words can tell the grief of Priam and Hecuba at this sight. His people could scarce restrain the aged king from rushing forth. He threw himself in the dust and besought them each by name to let him pass. Hecuba's distress was not less violent. The citizens stood round them weeping. The sound of the mourning reached the ears of Andromache, the wife of Hector, as she sat among her maidens at work; and anticipating evil she went forth to the wall. When she saw the horror there presented, she would have thrown herself headlong from the wall, but fainted and fell into the arms of her maidens. Recovering, she bewailed her fate, picturing to herself her country ruined, herself a captive, and her son, the youthful Astyanax, dependent for his bread on the charity of strangers.

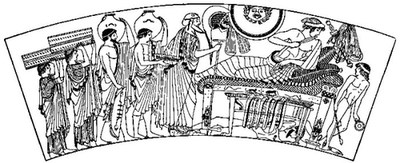

Fig. 160. Achilles over the Body of Hector at the Tomb of Patroclus

After Achilles and the Greeks had thus taken their revenge on the slayer of Patroclus, they busied themselves in paying due funeral rites to their friend.307 A pile was erected, and the body burned with due solemnity. Then ensued games of strength and skill, chariot races, wrestling, boxing, and archery. Later, the chiefs sat down to the funeral banquet, and finally retired to rest. But Achilles partook neither of the feast nor of sleep. The recollection of his lost friend kept him awake, – the memory of their companionship in toil and dangers, in battle or on the perilous deep. Before the earliest dawn he left his tent, and joining to his chariot his swift steeds, he fastened Hector's body to be dragged behind. Twice he dragged him round the tomb of Patroclus, leaving him at length stretched in the dust. But Apollo would not permit the body to be torn or disfigured with all this abuse; he preserved it free from taint or defilement.308

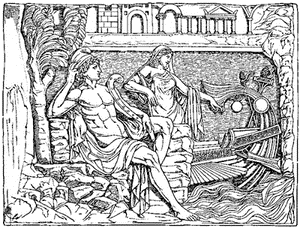

Fig. 161. Priam's Visit to Achilles

While Achilles indulged his wrath in thus disgracing Hector, Jupiter in pity summoned Thetis to his presence. Bidding her prevail on Achilles to restore the body of Hector to the Trojans, he sent Iris to encourage Priam to beg of Achilles the body of his son. Iris delivered her message, and Priam prepared to obey. He opened his treasuries and took out rich garments and cloths, with ten talents in gold and two splendid tripods and a golden cup of matchless workmanship. Then he called to his sons and bade them draw forth his litter and place in it the various articles designed for a ransom to Achilles. When all was ready, the old king with a single companion as aged as himself, the herald Idæus, drove forth from the gates, parting there with Hecuba his queen, and all his friends, who lamented him as going to certain death.

217. Priam in the Tent of Achilles. 309 But Jupiter, beholding with compassion the venerable king, sent Mercury to be his guide and protector. Assuming the form of a young warrior, Mercury presented himself to the aged couple; and, when at the sight of him they hesitated whether to fly or yield, approaching he grasped Priam's hand and offered to be their guide to Achilles' tent. Priam gladly accepted his service, and Mercury, mounting the carriage, assumed the reins and conveyed them to the camp. Then having cast the guards into a heavy sleep, he introduced Priam into the tent where Achilles sat, attended by two of his warriors. The aged king threw himself at the feet of Achilles and kissed those terrible hands which had destroyed so many of his sons. "Think, O Achilles," he said, "of thine own father, full of days like me, and trembling on the gloomy verge of life. Even now, mayhap, some neighbor chief oppresses him and there is none at hand to succor him in his distress. Yet, knowing that Achilles lives, he doubtless still rejoices, hoping that one day he shall see thy face again. But me no comfort cheers, whose bravest sons, so late the flower of Ilium, all have fallen. Yet one I had, one more than all the rest the strength of my age, whom fighting for his country thou hast slain. His body I come to redeem, bringing inestimable ransom with me. Achilles! reverence the gods! recollect thy father! for his sake show compassion to me!" These words moved Achilles, and he wept, remembering by turns his absent father and his lost friend. Moved with pity of Priam's silver locks and beard, he raised him from the earth and spake: "Priam, I know that thou hast reached this place conducted by some god, for without aid divine no mortal even in his prime of youth had dared the attempt. I grant thy request, for I am moved thereto by the manifest will of Jove." So saying he arose, went forth with his two friends, and unloaded of its charge the litter, leaving two mantles and a robe for the covering of the body. This they placed on the litter and spread the garments over it, that not unveiled it should be borne back to Troy. Then Achilles dismissed the old king, having first pledged himself to a truce of twelve days for the funeral solemnities.

As the litter approached the city and was descried from the walls, the people poured forth to gaze once more on the face of their hero. Foremost of all, the mother and the wife of Hector came, and at the sight of the lifeless body renewed their lamentations. The people wept with them, and to the going down of the sun there was no pause or abatement of their grief.

The next day, preparations were made for the funeral solemnities. For nine days the people brought wood and built the pile; and on the tenth they placed the body on the summit and applied the torch, while all Troy, thronging forth, encompassed the pyre. When it had completely burned, they quenched the cinders with wine, and, collecting the bones, placed them in a golden urn, which they buried in the earth. Over the spot they reared a pile of stones.

Such honors Ilium to her hero paid,And peaceful slept the mighty Hector's shade.310CHAPTER XXIII

THE FALL OF TROY

Fig. 162. Achilles and Penthesilea

218. The Fall of Troy. The story of the Iliad ends with the death of Hector, and it is from the Odyssey and later poems that we learn the fate of the other heroes. After the death of Hector, Troy did not immediately fall, but receiving aid from new allies, still continued its resistance. One of these allies was Memnon, the Ethiopian prince, whose story has been already told.311 Another was Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, who came with a band of female warriors. All the authorities attest the valor of these women and the fearful effect of their war cry. Penthesilea, having slain many of the bravest Greeks, was at last slain by Achilles. But when the hero bent over his fallen foe and contemplated her beauty, youth, and valor, he bitterly regretted his victory. Thersites, the insolent brawler and demagogue, attempting to ridicule his grief, was in consequence slain by the hero.312

219. The Death of Achilles. But Achilles himself was not destined to a long life. Having by chance seen Polyxena, daughter of King Priam, – perhaps on occasion of the truce which was allowed the Trojans for the burial of Hector, – he was captivated with her charms; and to win her in marriage, it is said (but not by Homer) that he agreed to influence the Greeks to make peace with Troy. While the hero was in the temple of Apollo negotiating the marriage, Paris discharged at him a poisoned arrow,313 which, guided by Apollo, fatally wounded him in the heel. This was his only vulnerable spot; for Thetis, having dipped him when an infant in the river Styx, had rendered every part of him invulnerable except that by which she held him.314

220. Contest for the Arms of Achilles. The body of Achilles so treacherously slain was rescued by Ajax and Ulysses. Thetis directed the Greeks to bestow her son's armor on that hero who of all survivors should be judged most deserving of it. Ajax and Ulysses were the only claimants. A select number of the other chiefs were appointed to award the prize. By the will of Minerva it was awarded to Ulysses, – wisdom being thus rated above valor. Ajax, enraged, set forth from his tent to wreak vengeance upon the Atridæ and Ulysses. But the goddess robbed him of reason and turned his hand against the flocks and herds of the Argives, which he slaughtered or led captive to his tent, counting them the rivals who had wronged him. Then the cruel goddess restored to him his wits. And he, fixing his sword in the ground, prepared to take his own life:

"Come and look on me,O Death, O Death, – and yet in yonder worldI shall dwell with thee, speak enough with thee;And thee I call, thou light of golden day,Thou Sun, who drivest on thy glorious car,Thee, for this last time, – never more again!O Light, O sacred land that was my home;O Salamis, where stands my father's hearth,Thou glorious Athens, with thy kindred race;Ye streams and rivers here, and Troïa's plains,To you that fed my life I bid farewell;This last, last word does Ajax speak to you;All else, I speak in Hades to the dead."[3]Then, falling upon his sword, he died. So, in the words of his magnanimous foe, Ulysses, passed to the god that ruleth in gloom

The best and bravest of the Argive host,Of all that came to Troïa, saving one,Achilles' self.315On the spot where his blood sank into the earth a hyacinth sprang up, bearing on its leaves the first two letters of his name, Ai, the Greek interjection of woe.316

Fig. 163. Œnone warning Paris

It was now discovered that Troy could not be taken but by the aid of the arrows of Hercules. They were in possession of Philoctetes, the friend who had been with Hercules at the last and had lighted his funeral pyre. Philoctetes317 had joined the Grecian expedition against Troy; but he accidentally wounded his foot with one of the poisoned arrows, and the smell from the wound proved so offensive that his companions carried him to the isle of Lemnos and left him there. Diomede and Ulysses, or Ulysses and Neoptolemus (son of Achilles), were now sent to induce him to rejoin the army. They succeeded. Philoctetes was cured of his wound by Machaon, and Paris was the first victim of the fatal arrows.

221. Paris and Œnone. In his distress Paris bethought him of one whom in his prosperity he had forgotten. This was the nymph Œnone, whom he had married when a youth and had abandoned for the fatal beauty of Helen. Œnone, remembering the wrongs she had suffered, refused to heal the wound; and Paris went back to Troy and died. Œnone quickly repented and hastened after him with remedies, but came too late, and in her grief hanged herself.

222. The Palladium. There was in Troy a celebrated statue of Minerva called the Palladium. It was said to have fallen from heaven, and the belief was that the city could not be taken so long as this statue remained within it. Ulysses and Diomede entered the city in disguise and succeeded in obtaining the Palladium, which they carried off to the Grecian camp.

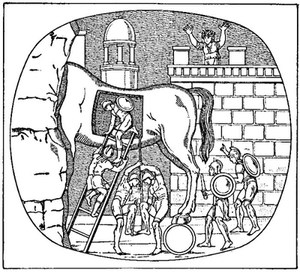

Fig. 164. The Wooden Horse

223. The Wooden Horse. But Troy still held out. The Greeks began to despair of subduing it by force, and by advice of Ulysses they resorted to stratagem.318 They pretended to be making preparations to abandon the siege; and a number of the ships were withdrawn and concealed behind a neighboring island. They then constructed an immense wooden horse, which they gave out was intended as a propitiatory offering to Minerva; but it was, in fact, filled with armed men. The rest of the Greeks then betook themselves to their ships and sailed away, as if for a final departure. The Trojans, seeing the encampment broken up and the fleet gone, concluded that the enemy had abandoned the siege. The gates of the city were thrown open, and the whole population issued forth, rejoicing at the long-prohibited liberty of passing freely over the scene of the late encampment. The great horse was the chief object of curiosity. Some recommended that it be taken into the city as a trophy; others felt afraid of it. While they hesitated, Laocoön, the priest of Neptune, exclaimed, "What madness, citizens, is this! Have you not learned enough of Grecian fraud to be on your guard against it? For my part, I fear the Greeks even when they offer gifts."319 So saying, he threw his lance at the horse's side. It struck, and a hollow sound reverberated like a groan. Then perhaps the people might have taken his advice and destroyed the fatal horse with its contents, but just at that moment a group of people appeared dragging forward one who seemed a prisoner and a Greek. Stupefied with terror, the captive was brought before the chiefs. He informed them that he was a Greek, Sinon by name; and that in consequence of the malice of Ulysses, he had been left behind by his countrymen at their departure. With regard to the wooden horse, he told them that it was a propitiatory offering to Minerva, and had been made so huge for the express purpose of preventing its being carried within the city; for Calchas the prophet had told them that if the Trojans took possession of it, they would assuredly triumph over the Greeks.

LAOCOÖN

224. Laocoön and the Serpents. This language turned the tide of the people's feelings, and they began to think how they might best secure the monstrous horse and the favorable auguries connected with it, when suddenly a prodigy occurred which left no room for doubt. There appeared advancing over the sea two immense serpents. They came upon the land and the crowd fled in all directions. The serpents advanced directly to the spot where Laocoön stood with his two sons. They first attacked the children, winding round their bodies and breathing pestilential breath in their faces. The father, attempting to rescue them, was next seized and involved in the serpent's coils.

… VainThe struggle; vain, against the coiling strainAnd gripe, and deepening of the dragon's grasp,The old man's clinch; the long envenomed chainRivets the living links, – the enormous aspEnforces pang on pang, and stifles gasp on gasp.320He struggled to tear them away, but they overpowered all his efforts and strangled him and the children in their poisonous folds. The event was regarded as a clear indication of the displeasure of the gods at Laocoön's irreverent treatment of the wooden horse, which they no longer hesitated to regard as a sacred object and prepared to introduce with due solemnity into the city. They did so with songs and triumphal acclamations, and the day closed with festivity. In the night the armed men who were inclosed in the body of the horse, being let out by the traitor Sinon, opened the gates of the city to their friends who had returned under cover of the night. The city was set on fire; the people, overcome with feasting and sleep, were put to the sword, and Troy completely subdued.

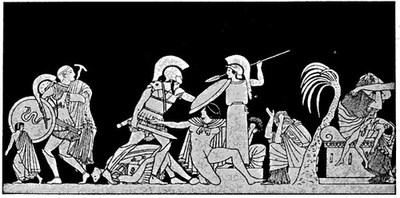

Fig. 165. The Sack of Troy

(Left half)

225. The Death of Priam. Priam lived to see the downfall of his kingdom and was slain at last on the fatal night when the Greeks took the city. He had armed himself and was about to mingle with the combatants,321 but was prevailed on by Hecuba to take refuge with his daughters and herself as a suppliant at the altar of Jupiter. While there, his youngest son, Polites, pursued by Pyrrhus, the son of Achilles, rushed in wounded and expired at the feet of his father; whereupon Priam, overcome with indignation, hurled his spear with feeble hand against Pyrrhus and was forthwith slain by him.

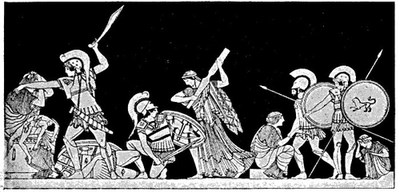

Fig. 166. The Sack of Troy

(Right half)

226. The Survivors. 322 Queen Hecuba and her daughter Cassandra were carried captives to Greece. Cassandra had been loved by Apollo, who gave her the gift of prophecy; but afterwards offended with her, he had rendered the gift unavailing by ordaining that her predictions should never be believed. Polyxena, another daughter, who had been loved by Achilles, was demanded by the ghost of that warrior and was sacrificed by the Greeks upon his tomb. Of the fate of the white-armed Andromache we have already spoken. She was carried off as the wife of Neoptolemus, but he was faithful to her for only a short time. After he had cast her aside she married Helenus, a brother of Hector, and still later returned to Asia Minor.

227. Helen, Menelaüs, and Agamemnon. On the fall of Troy, Menelaüs recovered possession of his wife, who, it seems, had not ceased to love him, though she had yielded to the might of Venus and deserted him for another.323 After the death of Paris, she aided the Greeks secretly on several occasions: in particular when Ulysses and Diomede entered the city in disguise to carry off the Palladium. She then saw and recognized Ulysses, but kept the secret and even assisted them in obtaining the image. Thus she became reconciled to Menelaüs, and they were among the first to leave the shores of Troy for their native land. But having incurred the displeasure of the gods, they were driven by storms from shore to shore of the Mediterranean, visiting Cyprus, Phœnicia, and Egypt. In Egypt they were kindly treated and presented with rich gifts, of which Helen's share was a golden spindle and a basket on wheels.

… Many yet adhereTo the ancient distaff at the bosom fixed,Casting the whirling spindle as they walk.… This was of old, in no inglorious days,The mode of spinning, when the Egyptian princeA golden distaff gave that beauteous nymph,Too beauteous Helen; no uncourtly gift.324Milton also alludes to a famous recipe for an invigorating draft, called Nepenthe, which the Egyptian queen gave to Helen:

Not that Nepenthes which the wife of ThoneIn Egypt gave to Jove-born Helena,Is of such power to stir up joy as this,To life so friendly or so cool to thirst.325At last, arriving in safety at Sparta, Menelaüs and Helen resumed their royal dignity, and lived and reigned in splendor; and when Telemachus, the son of Ulysses, in search of his father, arrived at Sparta, he found them celebrating the marriage of their daughter Hermione to Neoptolemus, son of Achilles.

Agamemnon326 was not so fortunate in the issue. During his absence his wife Clytemnestra had been false to him; and when his return was expected, she with her paramour, Ægisthus, son of Thyestes, laid a plan for his destruction. Cassandra warned the king, but as usual her prophecy was not regarded. While Agamemnon was bathing previous to the banquet given to celebrate his return, the conspirators murdered him.

Fig. 167. Orestes and Electra at the Tomb of Agamemnon

228. Electra and Orestes. It was the intention of the conspirators to slay his son Orestes also, a lad not yet old enough to be an object of apprehension, but from whom, if he should be suffered to grow up, there might be danger. Electra, the sister of Orestes, saved her brother's life by sending him secretly to his uncle Strophius, king of Phocis. In the palace of Strophius, Orestes grew up with the king's son Pylades, and formed with him a friendship which has become proverbial. Electra frequently reminded her brother by messengers of the duty of avenging his father's death; he, too, when he reached maturity, consulted the oracle of Delphi, which confirmed him in the design. He therefore repaired in disguise to Argos, pretending to be a messenger from Strophius, who would announce the death of Orestes. He brought with him what purported to be the ashes of the deceased in a funeral urn. After visiting his father's tomb and sacrificing upon it, according to the rites of the ancients, he met by the way his sister Electra. Mistaking her for one of the domestics, and desirous of keeping his arrival a secret till the hour of vengeance should arrive, he produced the urn. At once his sister, believing Orestes to be really dead, took the urn from him, and, embracing it, poured forth her grief in language full of tenderness and despair. Soon a recognition was effected, and the prince, with the aid of his sister, slew both Ægisthus and Clytemnestra.327