полная версия

полная версияThe Classic Myths in English Literature and in Art (2nd ed.) (1911)

Gazing amain from the marge of the flood-reverberant Dia,Chafing with ire, indignant, exasperate, – lo, Ariadne,Lorn Ariadne, beholds swift craft, swift lover retreating.Nor can be sure she sees what things she sees of a surety,When upspringing from sleep, she shakes off treacherous slumber,Lone beholds herself on a shore forlorn of the ocean.Carelessly hastens the youth, meantime, who, driving his oar-bladesHard in the waves, consigns void vows to the blustering breezes.But as, afar from the sedge, with sad eyes still the MinoïdMute as a Mænad in stone unmoving stonily gazes —Heart o'erwhelmed with woe – ah, thus, while thus she is gazing, —Down from her yellow hair slips, sudden, the weed of the fine-spunSnood, and the vesture light of her mantle down from the shouldersSlips, and the twisted scarf encircling her womanly bosom;Stealthily gliding, slip they downward into the billow,Fall, and are tossed by the buoyant flood at the feet of the fair one.Nothing she recks of the coif, of the floating garment as little,Cares not a moment then, whose care hangs only on Theseus, —Wretched of heart, soul-wrecked, dependent only on Theseus, —Desperate, woe-unselfed with a cureless sorrow incessant,Frantic, bosoming torture of thorns Erycina had planted…Then, they say, that at last, infuriate out of all measure,Once and again she poured shrill-voicèd shrieks from her bosom;Helpless, clambered steeps, sheer beetling over the surges,Whence to enrange with her eyes vast futile regions of ocean; —Lifting the folds, soft folds of her garments, baring her ankles,Dashed into edges of upward waves that trembled before her;Uttered, anguished then, one wail, her maddest and saddest, —Catching with tear-wet lips poor sobs that shivering choked her: —"Thus is it far from my home, O traitor, and far from its altars —Thus on a desert strand, – dost leave me, treacherous Theseus?Thus is it thou dost flout our vow, dost flout the Immortals, —Carelessly homeward bearest, with baleful ballast of curses?Never, could never a plea forfend thy cruelly mindedCounsel? Never a pity entreat thy bosom for shelter?..Hence, let never a maid confide in the oath of a lover,Never presume man's vows hold aught trustworthy within them!Verily, while in anguish of heart his spirit is longing,Nothing he spares to assever, nor aught makes scruple to promise:But, an his dearest desire, his nearest of heart be accorded —Nothing he recks of affiance, and reckons perjury, – nothing."Oh! what lioness whelped thee? Oh! what desolate cavern?What was the sea that spawned, that spat from its churning abysses,Thee, – what wolfish Scylla, or Syrtis, or vasty Charybdis,Thee, – thus thankful for life, dear gift of living, I gave thee?..Had it not liked thee still to acknowledge vows that we plighted,Mightest thou homeward, yet, have borne me a damsel beholden,Fain to obey thy will, and to lave thy feet like a servant,Fain to bedeck thy couch with purple coverlet for thee."But to the hollow winds why stand repeating my quarrel, —I, for sorrow unselfed, – they, but breezes insensate, —Potent neither voices to hear nor words to re-echo?..Yea, but where shall I turn? Forlorn, what succor rely on?'Haste to the Gnossian hills?' Ah, see how distantly surgingDeeps forbid, distending their gulfs abhorrent before me!'Comfort my heart, mayhap, with the loyal love of my husband?'Lo, the reluctant oar, e'en now, he plies to forsake me! —Nought but the homeless strand of an isle remote of the ocean!No, no way of escape, where the circling sea without shore is, —No, no counsel of flight, no hope, no sound of a mortal;All things desolate, dumb, yea, all things summoning deathward!Yet mine eyes shall not fade in death that sealeth the eyelids,Nor from the frame outworn shall fare my lingering senses,Ere, undone, from powers divine I claim retribution —Ere I call – in the hour supreme, on the faith of Immortals!"Come, then, Righters of Wrong, O vengeful dealers of justice,Braided with coil of the serpents, O Eumenides, ye ofBrows that blazon ire exhaling aye from the bosom,Haste, oh, haste ye, hither and hear me, vehement plaining,Destitute, fired with rage, stark-blind, demented for fury! —As with careless heart yon Theseus sailed and forgot me,So with folly of heart, may he slay himself and his household!"… Then with a nod supreme Olympian Jupiter nodded:Quaked thereat old Earth, – quaked, shuddered the terrified waters,Ay, and the constellations in Heaven that glitter were jangled.Straightway like some cloud on the inward vision of TheseusDropped oblivion down, enshrouding vows he had cherished,Hiding away all trace of the solemn behest of his father.

Fig. 143. Head of Dionysus

For, as was said before, Ægeus, on the departure of his son for Creta, had given him this command: "If Minerva, goddess of our city, grant thee victory over the Minotaur, hoist on thy return, when first the dear hills of Attica greet thy vision, white canvas to herald thy joy and mine, that mine eyes may see the propitious sign and know the glad day that restores thee safe to me."

… Even as clouds compelled by urgent push of the breezesFloat from the brow uplift of a snow-envelopèd mountain,So from Theseus passed all prayer and behest of his father.Waited the sire meanwhile, looked out from his tower over ocean,Wasted his anxious eyes in futile labor of weeping,Waited expectant, – saw to the southward sails black-bellied —Hurled him headlong down from the horrid steep to destruction, —Weening hateful Fate had severed the fortune of Theseus.Theseus, then, as he paced that gloom of the home of his father,Insolent Theseus knew himself what manner of evilHe with a careless heart had aforetime dealt Ariadne, —Fixed Ariadne that still, still stared where the ship had receded, —Wounded, revolving in heart her countless muster of sorrows.

Fig. 144. The Revels of Bacchus and Ariadne

178. Bacchus and Ariadne. But for the deserted daughter of Minos a happier fate was yet reserved. This island, on which she had been abandoned, was Naxos, loved and especially haunted by Bacchus, where with his train of reeling devotees he was wont to hold high carnival.

… Sweeping over the shore, lo, beautiful, blooming Iacchus, —Chorused of Satyrs in dance and of Nysian-born Sileni, —Seeking fair Ariadne, – afire with flame of a lover!Lightly around him leaped Bacchantès, strenuous, frenzied,Nodding their heads, "Euhoe!" to the cry, "Euhoe, O Bacchus!"Some – enwreathèd spears of Iacchus madly were waving;Some – ensanguined limbs of the bullock, quivering, brandished;Some – were twining themselves with sinuous snakes that twisted;Some – with vessels of signs mysterious, passed in procession —Symbols profound that in vain the profane may seek to decipher;Certain struck with the palms – with tapered fingers on timbrels,Others the tenuous clash of the rounded cymbals awakened; —Brayed with a raucous roar through the turmoil many a trumpet,Many a stridulous fife went, shrill, barbarian, shrieking.268So the grieving, much-wronged Ariadne was consoled for the loss of her mortal spouse by an immortal lover. The blooming god of the vine wooed and won her. After her death, the golden crown that he had given her was transferred by him to the heavens. As it mounted the ethereal spaces, its gems, growing in brightness, became stars; and still it remains fixed, as a constellation, between the kneeling Hercules and the man that holds the serpent.

179. The Amazons. As king of Athens, it is said that Theseus undertook an expedition against the Amazons. Assailing them before they had recovered from the attack of Hercules, he carried off their queen Antiope; but they in turn, invading the country of Athens, penetrated into the city itself; and there was fought the final battle in which Theseus overcame them.

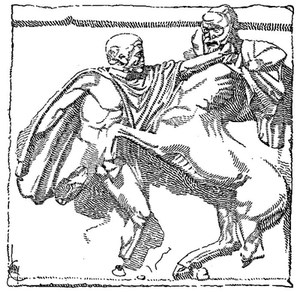

180. Theseus and Pirithoüs. A famous friendship between Theseus and Pirithoüs of Thessaly, son of Jupiter, originated in the midst of arms. Pirithoüs had made an irruption into the plain of Marathon and had carried off the herds of the king of Athens. Theseus went to repel the plunderers. The moment the Thessalian beheld him, he was seized with admiration, and stretching out his hand as a token of peace, he cried, "Be judge thyself, – what satisfaction dost thou require?" – "Thy friendship," replied the Athenian; and they swore inviolable fidelity. Their deeds corresponding to their professions, they continued true brothers in arms. When, accordingly, Pirithoüs was to marry Hippodamia, daughter of Atrax, Theseus took his friend's part in the battle that ensued between the Lapithæ (of whom Pirithoüs was king) and the Centaurs. For it happened that at the marriage feast, the Centaurs were among the guests; and one of them, Eurytion, becoming intoxicated, attempted to offer violence to the bride. Other Centaurs followed his example; combat was joined; Theseus leaped into the fray, and not a few of the guests bit the dust.

Fig. 145. Lapith and Centaur

Later, each of these friends aspired to espouse a daughter of Jupiter. Theseus fixed his choice on Leda's daughter Helen, then a child, but afterwards famous as the cause of the Trojan War; and with the aid of his friend he carried her off, only, however, to restore her at very short notice. As for Pirithoüs, he aspired to the wife of the monarch of Erebus; and Theseus, though aware of the danger, accompanied the ambitious lover to the underworld. But Pluto seized and set them on an enchanted rock at his palace gate, where fixed they remained till Hercules, arriving, liberated Theseus but left Pirithoüs to his fate.

181. Phædra and Hippolytus. After the death of Antiope, Theseus married Phædra, sister of the deserted Ariadne, daughter of Minos. But Phædra, seeing in Hippolytus, the son of Theseus, a youth endowed with all the graces and virtues of his father and of an age corresponding to her own, loved him. When, however, he repulsed her advances, her love was changed to despair and hate. Hanging herself, she left for her husband a scroll containing false charges against Hippolytus. The infatuated husband, filled, therefore, with jealousy of his son, imprecated the vengeance of Neptune upon him. As Hippolytus one day drove his chariot along the shore, a sea monster raised himself above the waters and frightened the horses so that they ran away and dashed the chariot to pieces. Hippolytus was killed, but by Æsculapius was restored to life, and then, removed by Diana from the power of his deluded father, was placed in Italy under the protection of the nymph Egeria.

In his old age, Theseus, losing the favor of his people, retired to the court of Lycomedes, king of Scyros, who at first received him kindly, but afterwards treacherously put him to death.

CHAPTER XIX

THE HOUSE OF LABDACUS

Fig. 146. Œdipus and the Sphinx

182. The Misfortunes of Thebes. Returning to the descendants of Inachus, we find that the curse which fell upon Cadmus when he slew the dragon of Mars followed nearly every scion of his house. His daughters, Semele, Ino, Autonoë, Agave, – his grandsons, Melicertes, Actæon, Pentheus, – lived sorrowful lives or suffered violent deaths. The misfortunes of one branch of his family, sprung from his son Polydorus, remain to be told. The curse seems to have spared Polydorus himself. His son Labdacus, also, lived a quiet life as king of Thebes and left a son, Laïus, upon the throne. But erelong Laïus was warned by an oracle that there was danger to his throne and life if his son, new-born, should reach man's estate. He, therefore, committed the child to a herdsman with orders for its destruction; but the herdsman, moved with pity yet not daring entirely to disobey, pierced the child's feet, purposing to expose him to the elements on Mount Cithæron.

183. Œdipus and the Sphinx. 269 In this plight the infant was given to a tender-hearted fellow-shepherd, who carried him to King Polybus of Corinth and his queen, by whom he was adopted and called Œdipus, or Swollen-foot.

Many years afterward, Œdipus, learning from an oracle that he was destined to be the death of his father, left the realm of his reputed sire, Polybus. It happened, however, that Laïus was then driving to Delphi, accompanied only by one attendant. In a narrow road he met Œdipus, also in a chariot. On the refusal of the youthful stranger to leave the way at their command, the attendant killed one of his horses. Œdipus, consumed with rage, slew both Laïus and the attendant, and thus unknowingly fulfilled both oracles.

Shortly after this event, the city of Thebes, to which Œdipus had repaired, was afflicted with a monster that infested the high-road. She was called the Sphinx. She had the body of a lion and the upper part of a woman. She lay crouched on the top of a rock and, arresting all travelers who came that way, propounded to them a riddle, with the condition that those who could solve it should pass safe, but those who failed should be killed. Not one had yet succeeded in guessing it. Œdipus, not daunted by these alarming accounts, boldly advanced to the trial. The Sphinx asked him, "What animal is it that in the morning goes on four feet, at noon on two, and in the evening upon three?" Œdipus replied, "Man, who in childhood creeps on hands and knees, in manhood walks erect, and in old age goes with the aid of a staff." The Sphinx, mortified at the collapse of her riddle, cast herself down from the rock and perished.

184. Œdipus, the King. In gratitude for their deliverance, the Thebans made Œdipus their king, giving him in marriage their queen, Jocasta. He, ignorant of his parentage, had already become the slayer of his father; in marrying the queen he became the husband of his mother. These horrors remained undiscovered till, after many years, Thebes being afflicted with famine and pestilence, the oracle was consulted, and, by a series of coincidences, the double crime of Œdipus came to light. At once, Jocasta put an end to her life by hanging herself. As for Œdipus, horror-struck, —

When her formHe saw, poor wretch! with one wild fearful cry,The twisted rope he loosens, and she fell,Ill-starred one, on the ground. Then came a sightMost fearful. Tearing from her robe the clasps,All chased with gold, with which she decked herself,He with them struck the pupils of his eyes,With words like these: "Because they had not seenWhat ills he suffered, and what ills he did,They in the dark should look, in time to come,On those whom they ought never to have seen,Nor know the dear ones whom he fain had known."With suchlike wails, not once or twice alone,Raising his eyes he smote them, and the balls,All bleeding, stained his cheek.270185. Œdipus at Colonus. After these sad events Œdipus would have left Thebes, but the oracle forbade the people to let him go. Jocasta's brother, Creon, was made regent of the realm for the two sons of Œdipus. But after Œdipus had grown content to stay, these sons of his, with Creon, thrust him into exile. Accompanied by his daughter Antigone, he went begging through the land. His other daughter, Ismene, at first stayed at home. Cursing the sons who had abandoned him, but bowing his own will in submission to the ways of God, Œdipus approached the hour of his death in Colonus, a village near Athens. His friend Theseus, king of Athens, comforted and sustained him to the last. Both his daughters were also with him:

And then he called his girls, and bade them fetchClear water from the stream, and bring to himFor cleansing and libation. And they went,Both of them, to yon hill we look upon,Owned by Demeter of the fair green corn,And quickly did his bidding, bathed his limbs,And clothed them in the garment that is meet.And when he had his will in all they did,And not one wish continued unfulfilled,Zeus from the dark depths thundered, and the girlsHeard it, and shuddering, at their father's knees,Falling they wept; nor did they then forbearSmiting their breasts, nor groanings lengthened out;And when he heard their bitter cry, forthwithFolding his arms around them, thus he spake:"My children, on this day ye cease to haveA father. All my days are spent and gone;And ye no more shall lead your wretched life,Caring for me. Hard was it, that I know,My children! Yet one word is strong to loose,Although alone, the burden of these toils,For love in larger store ye could not haveFrom any than from him who standeth here,Of whom bereaved ye now shall live your life."271There was sobbing, then silence. Then a voice called him, – and he followed. God took him from his troubles. Antigone returned to Thebes, – where, as we shall see, her sisterly fidelity showed itself as true as, aforetime, her filial affection.

Her brothers, Eteocles and Polynices, had meanwhile agreed to share the kingdom between them and to reign alternately year by year. The first year fell to the lot of Eteocles, who, when his time expired, refused to surrender the kingdom to his brother. Polynices, accordingly, fled to Adrastus, king of Argos, who gave him his daughter in marriage and aided him with an army to enforce his claim to the kingdom. These causes led to the celebrated expedition of the "Seven against Thebes," which furnished ample materials for the epic and tragic poets of Greece. And here the younger heroes of Greece make their appearance.

CHAPTER XX

MYTHS OF THE YOUNGER HEROES: THE SEVEN AGAINST THEBES

186. Their Exploits. The exploits of the sons and grandsons of the chieftains engaged in the Calydonian Hunt and the Quest of the Golden Fleece are narrated in four stories, – the Seven against Thebes, the Siege of Troy, the Wanderings of Ulysses, and the Adventures of Æneas.

187. The Seven against Thebes. 272 The allies of Adrastus and Polynices in the enterprise against Thebes were Tydeus of Calydon, half brother of Meleager, Parthenopæus of Arcadia, son of Atalanta and Mars, Capaneus of Argos, Hippomedon of Argos, and Amphiaraüs, the brother-in-law of Adrastus. Amphiaraüs opposed the expedition for, being a soothsayer, he knew that none of the leaders except Adrastus would live to return from Thebes; but on his marriage to Eriphyle, the king's sister, he had agreed that whenever he and Adrastus should differ in opinion, the decision should be left to Eriphyle. Polynices, knowing this, gave Eriphyle the necklace of Harmonia and thereby gained her to his interest. This was the selfsame necklace that Vulcan had given to Harmonia on her marriage with Cadmus; Polynices had taken it with him on his flight from Thebes. It seems to have been still fraught with the curse of the house of Cadmus. But Eriphyle could not resist so tempting a bribe. By her decision the war was resolved on, and Amphiaraüs went to his fate. He bore his part bravely in the contest, but still could not avert his destiny. While, pursued by the enemy, he was fleeing along the river, a thunderbolt launched by Jupiter opened the ground, and he, his chariot, and his charioteer were swallowed up.

It is unnecessary here to detail all the acts of heroism or atrocity which marked this contest. The fidelity, however, of Evadne stands out as an offset to the weakness of Eriphyle. Her husband, Capaneus, having in the ardor of the fight declared that he would force his way into the city in spite of Jove himself, placed a ladder against the wall and mounted; but Jupiter, offended at his impious language, struck him with a thunderbolt. When his obsequies were celebrated, Evadne cast herself on his funeral pile and perished.

Fig. 147. Eteocles and Polynices kill each other

It seems that early in the contest Eteocles consulted the soothsayer Tiresias as to the issue. Now, this Tiresias in his youth had by chance seen Minerva bathing, and had been deprived by her of his sight, but afterwards had obtained of her the knowledge of future events. When consulted by Eteocles, he declared that victory should fall to Thebes if Menœceus, the son of Creon, gave himself a voluntary victim. The heroic youth, learning the response, threw away his life in the first encounter.

The siege continued long, with varying success. At length both hosts agreed that the brothers should decide their quarrel by single combat. They fought, and fell each by the hand of the other. The armies then renewed the fight; and at last the invaders were forced to yield, and fled, leaving their dead unburied. Creon, the uncle of the fallen princes, now became king, caused Eteocles to be buried with distinguished honor, but suffered the body of Polynices to lie where it fell, forbidding any one, on pain of death, to give it burial.

188. Antigone,273 the sister of Polynices, heard with indignation the revolting edict which, consigning her brother's body to the dogs and vultures, deprived it of the rites that were considered essential to the repose of the dead. Unmoved by the dissuading counsel of her affectionate but timid sister, and unable to procure assistance, she determined to brave the hazard and to bury the body with her own hands. She was detected in the act. When Creon asked the fearless woman whether she dared disobey the laws, she answered:

Yes, for it was not Zeus who gave them forth,Nor justice, dwelling with the gods below,Who traced these laws for all the sons of men;Nor did I deem thy edicts strong enough,That thou, a mortal man, should'st overpassThe unwritten laws of God that know no change.They are not of to-day nor yesterday,But live forever, nor can man assignWhen first they sprang to being. Not through fearOf any man's resolve was I preparedBefore the gods to bear the penaltyOf sinning against these. That I should dieI knew (how should I not?), though thy decreeHad never spoken. And before my timeIf I shall die, I reckon this a gain;For whoso lives, as I, in many woes,How can it be but he shall gain by death?And so for me to bear this doom of thineHas nothing fearful. But, if I had leftMy mother's son unburied on his death,In that I should have suffered; but in thisI suffer not.274Creon, unyielding and unable to conceive of a law higher than that he knew, gave orders that she should be buried alive, as having deliberately set at nought the solemn edict of the city. Her lover, Hæmon, the son of Creon, unable to avert her fate, would not survive her, and fell by his own hand. It is only after his son's death and as he gazes upon the corpses of the lovers, that the aged Creon recognizes the insolence of his narrow judgment. And those that stand beside him say:

Man's highest blessednessIn wisdom chiefly stands;And in the things that touch upon the gods,'T is best in word or deed,To shun unholy pride;Great words of boasting bring great punishments,And so to gray-haired ageTeach wisdom at the last.275189. The Epigoni. 276 Such was the fall of the house of Labdacus. The bane of Cadmus expires with the family of Œdipus. But the wedding gear of Harmonia has not yet fulfilled its baleful mission. Amphiaraüs had, with his last breath, enjoined his son Alcmæon to avenge him on the faithless Eriphyle. Alcmæon engaged his word, but before accomplishing the fell purpose, he was ordered by an oracle of Delphi to conduct against Thebes a new expedition. Thereto his mother Eriphyle, influenced by Thersander, the son of Polynices, and bribed this time by the gift of Harmonia's wedding garment, impelled not only Alcmæon but her other son, Amphilochus. The descendants (Epigoni) of the former Seven thus renewed the war against Thebes. They leveled the city to the ground. Its inhabitants, counseled by Tiresias, took refuge in foreign lands. Tiresias himself perished during the flight. Alcmæon, returning to Argos, put his mother to death but, in consequence, repeated in his own experience the penalty of Orestes. The outfit of Harmonia preserved its malign influence until, at last, it was devoted to the temple at Delphi and removed from the sphere of mortal jealousies.