полная версия

полная версияThe Mission to Siam, and Hué the Capital of Cochin China, in the Years 1821-2

Further proofs of the superstitious nature of this people were easily furnished. The belief in the agency of evil spirits is universal, and though disclaimed by the religion of Buddha, they are more frequently worshipped than the latter. Nor will the darker periods of German necromancy and pretended divination be found to exceed, in point of the incredible and the horrible, what is to be observed amongst the Siamese of the present day.

It is usual to inter women that have died pregnant; the popular belief is that the necromancers have the power of performing the most extraordinary things when possessed of the infant which had been thus interred in the womb of the mother: it is customary to watch the grave of such persons, in order to prevent the infant from being carried off. The Siamese tell the tale of horror in the most solemn manner. All the hobgoblins, wild and ferocious animals, all the infernal spirits are said to oppose the unhallowed deed; the perpetrator, well charged with cabalistic terms, which he must recite in a certain fixed order, and with nerves well braced to the daring task, proceeds to the grave, which he lays open. In proportion as he advances in his work the opposing sprites become more daring; he cuts off the head, hands, and feet of the infant, with which he returns home. A body of clay is adapted to these, and this new compound is placed in a sort of temple; the matter is now accomplished, the possessor has become master of the past, present, and future.

The funeral ceremonies observed on the death of a king are somewhat different from those mentioned above, but the principle is the same. All the people go into mourning. All ranks and both sexes shave the head, and this ceremony is repeated a third time. An immense concourse is assembled to witness the combustion of the body. The ceremony is said to constitute the most imposing spectacle which the country at any time can boast.

Within the first enclosure a line of priests are seated, reciting prayers from the sacred books, in a loud voice. Behind them the new king has taken his station. In the succeeding enclosures the princes of the royal family and other persons of distinction have taken their places. It will be seen by the manner in which the funeral-pile is lighted, how much attention has been bestowed upon the arrangement even of the most trivial matters. A train is laid from the pile to the place where the king stands, others to those occupied by the princes of the family, with this distinction in their distribution, that the train laid to the king’s station is the only one that directly reaches the pile. That of the next person in rank joins this at a little distance, and so of the others, in the order of rank. These trains are fired all at the same moment.

The outer circle of all is allotted to the performance of plays, gymnastic exercises, and feats of dexterity, and sleight of hand. The plays are divided into Siamese, Barman, Pegu, Laos, and Chinese; and they are so called more from the performers being of these several countries, than from any essential difference in the drama.

The external forms of reverence for the deceased king are impressive and unbounded; and the image formed from his ashes, being placed upon the altar, claims scarce less devotion than that of Buddha himself. That during life, while he yet grasped the sceptre, and made his subjects tremble, he should impiously assume the attributes of divinity, and claim from the unwilling mind the adoration due only to the Deity, seems even less strange, and less revolting, than this shameful, because voluntary prostitution of human intellect.

LAWSWhere the government is perfectly despotic, it will readily be conceived that law and right are but empty names, at least, as far as regards the king, and his under-despots; that, in fact, power is law, and right, and justice. Yet where the interests of these are not directly involved, we shall find in the system of laws a marked attention to distributive justice on the part of government. Necessity itself dictates this policy, without which no government could long exist. Under this form of administration the laws are often strictly equitable, and severely just. Yet though the laws are good, the propounders of them are in general corrupt; and where the channels of justice are tarnished, it matters little to the people that they have derived good laws from their ancestors.

ADULTERYThe laws regarding this crime have undergone considerable changes, and seem to have kept pace with the state of civilization. Anciently, the punishment was left entirely in the hands of the injured husband, the government taking no cognizance of the affair. He could put one or both of the offending parties to death in what manner he chose. Compensation in money or goods often reconciled the parties. Subsequently, this unlimited power was taken out of the hands of the individual, and the law declared that the husband had a right to put both the offending parties to death upon the spot, but not one alone. The punishment, to be legal, must have been inflicted instantly, and without deliberation. The present laws have left no part of the punishment in the hands of individuals; the crime is punishable only by fine. The amount of the fine, though fixed, is in proportion to the rank of the criminal. Thus, a man of low rank, offending in this manner, his equal, or one of superior rank, pays two catties of silver, about two hundred Bengal rupees, or twenty-five pounds sterling. A man of rank again pays six catties.

It is reckoned a capital crime to seduce any female belonging to the palace.

THEFT – DEBTThe laws regarding theft are in many instances particularly severe. After restoring the property or its value to the rightful owner, a fine is imposed, and the culprit is cast into prison, for a longer or shorter period, during which he is obliged not only to maintain himself, but he is made to pay for light, and even for his lodging. Of the greater number of debtors, begging is the only means of existence. They are supplied with food by the people as they pass along in chains through the bazar. Their necessities impel them to greater crimes, and they ultimately become involved in perpetual slavery. Yet the Siamese are undoubtedly a very charitable people, and appear to take delight in assisting the needy, feeding the hungry, and helping the wretched. Nor is this virtue in them connected with ostentation. Wherever want exists, wherever distress is observed, there their aid is freely bestowed.

HISTORYMy information on this subject is extremely scanty, and extends back but a few years.

The principal event which has occurred of late years in the history of Siam, is the capture of the old capital Yuthia, by the Barmans, under their ambitious and enterprising leader Luong Pra, whom Captain Symes calls by the name of Alompra. This took place in the year 1767. The king was at the same time taken prisoner, and by this decisive blow, the Barmans may be said to have effected the entire conquest of the country. Yet their footing was insecure. The people were rather dispirited than subdued, and their long-cherished hatred of the Barmans had undergone no change. In this state of things, a leader soon started up amongst them, who though of foreign extraction, speedily acquired influence from success.

Pe-ya-tac, the son of a wealthy China-man, by a Siamese woman, had been brought up as a menial in the palace of the king, who became attached to him as he grew up. He obtained the government of the province called Muong-tac, where he conducted himself to the satisfaction of his master, and amassed great wealth.

The war with the Barmans was soon followed by famine. Pe-ya-tac had, on the approach of the enemy, removed with his wealth to the province of Chantibond. In this remote quarter, his generosity fed multitudes who were starving. He collected around him the dispirited inhabitants, and ventured to make head against the enemy. His first efforts were crowned with success; his followers increased in number, victory led on to victory, until he saw the enemy expelled, and himself at the head of the nation. He declared himself king, and removed the capital of the kingdom from Yuthia to Bankok. He fortified the place, and built himself a palace which is still to be seen. Every second or third year, he was involved in war with the Barmans, whom he always repulsed. He not only recovered all the former dominions of the kingdom, but added to them. Having subdued his enemies, he next turned his attention to the peaceful arts.

He readily appreciated the superior industry of his countrymen, and granted them peculiar privileges. He behaved with the greatest moderation, and is still extolled for his regard of justice.

In the latter years of his reign, his conduct became greatly changed. The combined influence of suspicion and fanaticism rendered him an object of general dread. At the same time the most sordid avarice took possession of his mind, and led to the commission of numerous acts of cruelty. The father of the present king headed a conspiracy against him, and put him to death. The massacres which took place on this occasion were less numerous than was to have been expected from the existing state of society and public opinion.

We know but little of the character of the successor to Pe-ya-tac, but that the kingdom readily yielded to him. He died in 1782, and the present king ascended the throne at the same time.

The first public act of the present king’s reign was inauspicious. He was yet scarcely seated on his throne, before he put to death his nephew, the Prince Chau-pha, with upwards of a hundred persons of rank, who were supposed to be too much attached to the latter. The pretensions of Chau-pha to the throne were, if they had any existence, but ill-supported. His popularity was the cause of his ruin. The death of so many persons of distinction, some of whom had rendered themselves famous in war against the Barmans, was displeasing to the people, and occasioned considerable discontent, which nothing but the subsequent good conduct of the king could have overcome.

The present king has been engaged in almost constant wars with the Barmans; and it is the boast of his reign that he has lost nothing in the contest. The Malay and other dependent states have made no effort to throw off the yoke. Yet the kingdom is but little indebted to the government for the tranquillity which it has enjoyed. Nothing can be conceived more weak, or more contemptible, than the measures instituted for its defence.

It would seem as if it feared its own subjects as its greatest enemies; as if it dreaded domestic sedition, more than an attack from abroad. The country lies open in every quarter, without even a shew of defence. Thus it must ever be with governments founded on despotism. All confidence must be destroyed, where the interests of the people are trampled upon.

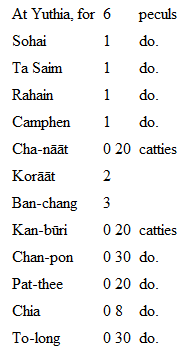

REVENUEThe land-tax is paid chiefly in kind. Besides this, a considerable revenue is derived from the privilege of fishing in rivers, and of distilling arrack. Other taxes are levied in a more odious and oppressive manner, as in the case of commercial and other monopolies. The principal of these are monopolies of sugar, pepper, benzoin, agila wood, and, in short, of all valuable commodities. They are delivered to the king at a fixed price.

Arrack is consumed almost exclusively by the Chinese, and the manufacture of it is entirely in their hands.

The privilege of distilling arrack at Bankok, is let for eighteen peculs of silver = 72,000 ticals17,

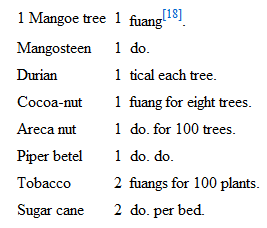

Fruit trees, &c., are taxed as follows: —

18A fuang is the eighth part of a tical.

No other fruits pay duty.

The revenue derived from fruit trees alone, is said to amount to 7000 catties of silver.

That derived from the gambling houses is said to equal that from arrack.

The privilege of fishing in rivers is said to be let for eight peculs.

NUMERALSThe notation of the Siamese seems to be exactly similar in principle to our own, and is evidently derived from the mode used in Sanskrit, from some ancient form of which the notation of Arabia and the west has branched off.

1 Nung.

2 Sōng.

3 Sāām.

4 Sēē.

5 Hāā.

6 Hōc.

7 Chāyt.

8 Pāyt.

9 Kao.

10 Seep.

11 See-bayt.

12 Seep-sōng.

13 Seep-sāām.

14 Seep-see.

15 Seep-hāā.

16 Seep-hōc.

17 Seep-chayt.

18 Seep-payt.

19 Seep-kao.

20 Y-seep.

21 Y-see-boyt.

30 Sāām-sēēp.

40 See-seep.

50 Hāā-seep.

60 Hoc-seep.

7 °Chayt-seep.

80 Payt-seep.

90 Kao-seep.

100 Roy.

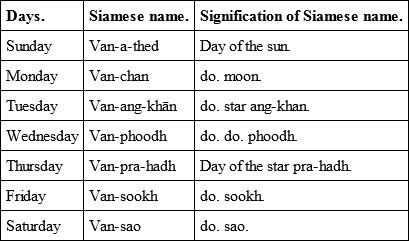

DAYS OF THE WEEK

The Siamese year commences with the first moon in December. At the close of the year there is a grand festival, called the feast of the souls of the dead. At this period also the Siamese propitiate the elements; the fire, the air, the earth, and water. Water is the favourite element. Rivers claim the greatest share in this festival. Rice and fruits are thrown into the stream; a thousand fantastic toys are set afloat on the water; thousands of floating lamps cast a flickering light upon the scene, and the approach of evening is hailed as the season of innocent amusement, as well as of religious duty.

The Siamese affect to bestow great attention upon the construction of their calendar. There is little difference between it and that of the Chinese; and it is very doubtful if they could construct one without the assistance of the latter, which they procure regularly from Pekin. Formerly a Brahman was entertained at court for the purpose of regulating the calendar. That office is now executed by a native of the country, by name Pra-hora.

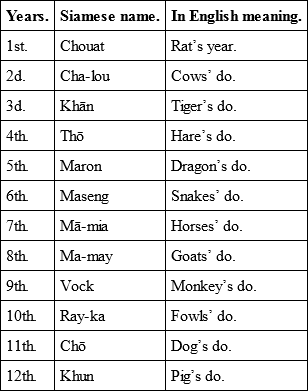

The Siamese years are divided as below into duodecennial periods, thus:

Our inquiries respecting the origin of the Bauddhic religion amongst the Siamese have been attended with but little success; nor do they leave us much ground to hope that any documents or writings they possess are calculated to throw any certain or steady light upon this interesting, but very obscure, subject.

The general persuasion amongst the priests, however, is, that it had its origin in the country called Lanka18, which they acknowledge to be Ceylon, for which island they still entertain the highest reverence, and imagine that there the doctrines of their faith are contained in their greatest purity. Others maintain that it had its origin in the country called Kabillah Path, the common name amongst the Siamese for Europe; while others again assert it to be of domestic origin, and taught by a man sent from God.

The person who taught them this religion is known under various names, as,

Ong-Sam-ma, Sam Puttho, which is said to mean Omnipotens.

Sommonokodam, i. e., one who steals cattle. Phut, and Phuti. (Pati, a lord?)

Prā-phut, the high Lord.

Pra-phuti-roop, i. e., the image of the high Lord.

Before he was considered sacred, his name was Prā-si Thāāt.

He is said to have been born of a father called Soori-soo-thoght, and of a mother called Pra-Soori-maha-maya.

Other names of Buddha: —

Y-thee-pee-so. Pā-kā-wā. Ora-hang.

They state that 2340 years have elapsed since the religion was first introduced; a date which is said to be stated in their sacred books, and particularly in that called Pra-sak-ka-rah, which was written by Buddha himself, or at least under his direction.

He commenced the task of converting men, by teaching them a more civilized mode of life, directing them to avoid rapine and plunder; to cultivate the soil and to lay aside their ferocious manners, and to live in peace with each other, and with all other animals of the creation.

His commands were, at first, but five; they were afterwards increased to eight. The five first alone are essential to the salvation of man, and he who observes them will assuredly merit heaven. These five are more particularly calculated for the lower orders; but it is very meritorious to observe the other three.

Commands of Buddha: —

1.19 Panna Thi-bāt, ham-mi kha Satt.

You shall not kill an animal or living creature of any kind.

2. Ad thi ma than, ham-mi hai lac sab.

You shall not steal any thing.

3. Kham-mi sumi cha-chān, ham-mi hai somg sel năi phi ri yan than puun.

You shall not have intercourse with the wives of other men.

4. Moo-sa va tha, ham mi hai phût kohoc sab plab.

You shall not speak an untruth or any falsehood on any occasion.

5. Sura me rai, hai mi hai dūūm kin sung nam maou.

You shall not drink any intoxicating liquor, or any substance calculated to intoxicate.

6. Ka me sumitsa cham, ham-mi hai non kab mia.

During the increase of the moon, you shall not, on the 8th, or on the 15th, have connexion with woman.

N.B. These two days are called von-prā, i. e., Dies Domini, the days of the Pra.

7. Vi ka la po chana, ham-mi hai kin khong nōek vela.

You shall not eat after mid-day.

8. Oocha se jana, ham mi hai nōn nūa thiang an vi chit ang gnam.

It is not becoming to sleep on costly, soft, rich, and elevated beds. You shall sleep on a clean mat.

There are, as has been already observed, set days, on which it is proper to worship at the temples, as on the 8th and 15th of the moon. There are also other days that are held sacred, and they are pointed out as such by persons who profess to be acquainted with judicial astrology. This sort of divination, however, is not cultivated by the priests, who affect to consider it as profane and improper. Yet when the astrologers have pointed out particular days as proper for devotion, or as being lucky or the contrary, the priests observe them.

It is customary for every Siamese to enter the rank of priests in the course of his life. He may remain in it or leave it at pleasure.

PROVINCE OF CHANTIBOONA, or CHANTIBONDThe reverses of fortune which this province has undergone, within a comparatively short period, have been remarkable. It for a long time belonged to the ancient kingdom of Cambodia, but on the partition of that admired and beautiful, but unfortunate country, was seized upon by the Cochin-Chinese. It has since passed into the hands of the king of Siam, and has constituted an integral part of his dominions since the reign of the Chinese king.

Chantibond is a mountainous country, forming the eastern boundary of the kingdom of Siam, dividing it from Cambodia, and situated at the head of the Gulf of Siam. It is said to be one of the richest and most valuable provinces of the king of Siam. It is singularly beautiful and picturesque, diversified by lofty mountains, extensive forests, and fertile vallies and plains. The passage thence to Cambodia is of short distance, a ridge of mountains dividing the two countries. It possesses a good and convenient harbour, well protected by numerous beautiful islands in front. The river is obstructed in a great measure at its mouth, but affords convenient and safe navigation to small vessels and boats. It once possessed an extensive and profitable commerce, which has been upon the decline since the place fell into the hands of the Siamese. The produce of the country is annually removed to Bankok, and the commerce with foreign ships is prohibited.

The principal productions are pepper, the cultivation of which may be increased almost to an unlimited extent, benzoin, lac, ivory, agila wood, rhinoceros’ horns, hides of cows, buffaloes, deer, &c., gamboge, some cardamoms, and precious stones, the latter of inferior quality. The forests abound in excellent timber, and afford the best materials for ship-building: accordingly, many junks are built at this place. Many of the islands in front of the port, and particularly that called Bangga-cha, produce abundance of precious stones. The island Sa-ma-ra-yat, to the east of the harbour, is said to produce gold. In the former of these islands, there is a safe and convenient harbour.

At a short distance from the coast, there is a very high mountain, called Bomba-soi, commanding an extensive view both of Chantibond and of Cambodia.

The amount of population is uncertain, some stating that it amounts to nearly one million, while others reckon it under half that number. It is composed of Chinese, Cochin Chinese, Cambodians, and Siamese; but by far the greater number are Chinese, in whose hands are all the wealth, and the richest products of the country. There are also from two to three hundred native Christians in the place, who, like those in other parts of Siam, are placed under the care of the bishop of Metellopolis, Joseph Florens, a Frenchman.

The place is governed by a man of Chinese extraction, appointed by the king of Siam.

Of pepper, the principal object of culture, the annual produce, at the present time, is said to amount to 20,000 peculs. It is sold to the king on the spot, for eight ticals a pecul. The price in Bankok is eighteen.

The cardamoms produced in Chantibond are reckoned of inferior quality. Those of Cambodia are reckoned the best. They are purchased on the spot by the king, for 120 or 140 ticals, and re-sold at Bankok for 270, 280, and even 300. They are carried exclusively to China, where they are held in high esteem.

The agila wood of Chantibond is reckoned among the best, and is only equalled by that of Cochin China.

The consumption of this highly odoriferous substance is very considerable even in Siam, but the greatest part is exported to China. Its use is of the highest antiquity, and it has in general been allotted chiefly for sacred purposes, for the service of the temple, and the solemn ceremonies of funeral rites. Much of it is consumed in the combustion of bodies of persons of distinction. The Chinese would appear to use it chiefly in their temples, both public and private, and as every Chinese house is furnished with a small temple for the reception of their household gods, the consumption of this wood by them must be very extensive. It is used in a very economical and neat mode. A quantity of the wood is first reduced to a fine powder, which, being mixed with a gummy substance, is laid over a small slip of soft wood, about the size of a bull-rush, so as to form a tolerably thick coating. These small sticks are stuck on end in the temple, and being lighted, give out a feeble but grateful perfume, the substance burning with a slow and smothered flame. This sort of taper is made up into bundles, wrapt up in fine paper, and sold in almost every shop.

The odoriferous principle in agila wood resides in a black, thick, concrete oil, resembling tar or resin while burning20. It is disposed in numerous cells, and gives to the wood a blackish, dotted appearance. It is generally asserted that this is the effect of a disease in the tree; but the opinion may well be called in question. It would rather seem to be the natural effect of a necessary modification of the living principle of the plant itself, no more partaking of the nature of disease than an inevitable and destined change and termination of life can be said to constitute such a state.

The odoriferous part is found in comparatively few trees, and those chiefly where the trees have either died, or have been possessed of feeble remains of vitality. The perfect trees, those bearing leaves, or fruit in perfection, rarely possess any part of it: neither does it appear to depend much upon the size of the tree, small ones often affording it in large quantity, while large ones yield very little or none at all. Is it not probable that it proceeds from an effort of nature to support the feeble remains of vegetable life? In this case, the juices of the plant, like the blood of animals, retreat towards the centre, where they still, for a time, maintain the feeble spark. The oil, in the case of this plant, is secreted in larger quantity; and accumulating in the thicker and central parts of the tree, and towards the root, forms the substance in question.