полная версия

полная версияA. D. 2000

“And you knew that a letter would be found in that cairn?” inquired Lester, with intense surprise.

“I was told so by Brainard,” Cobb answered, with quiet unconcern.

“And you personally knew the man who left that letter here in this desolate waste?” incredulously broke in Hugh.

“Intimately.”

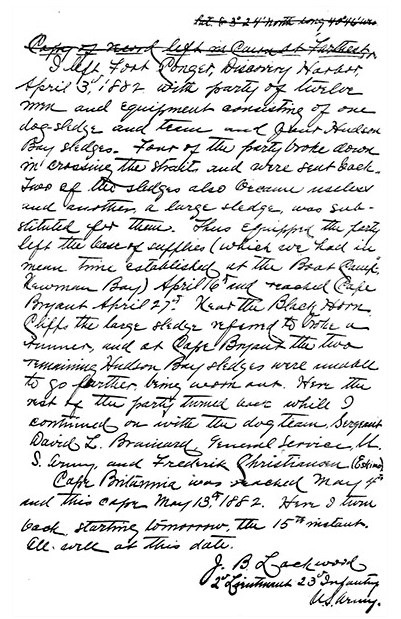

Copy of record left in Cairn at Farthest.

I left Fort Conger, Discovery Harbor, April 3d, 1882 with party of twelve men and equipment consisting of one dog-sledge and team and four Hudson Bay sledges. Four of the party broke down in crossing the straits and were sent back. Two of the sledges also became useless and another, a large sledge, was substituted for them. Thus equipped the party left the base of supplies (which we had in mean time established at the Boat Camp, Newman Bay) April 16th and reached Cape Bryant April 27th. Near the Black Horn Cliffs the large sledge referred to broke a runner, and at Cape Bryant the two remaining Hudson Bay sledges were unable to go farther, being worn out. Here the rest of the party turned back while I continued on with the dog team. Sergeant David L. Brainard, General Service, U. S. Army, and Frederik Christiansen (Eskimo).

Cape Britannia was reached May 4th and this cape May 13th, 1882. Here I turn back starting tomorrow, the 15th instant. All well at this date.

J. B. Lockwood2d Lieutenant 23d InfantryU.S. Army.Cobb then detailed all the circumstances attending the fit-out of the Greely expedition, and his personal acquaintance with Brainard and Lockwood. He narrated that they had reached this memorable spot on the 13th of May, 1882, and could go no farther, as a great sea washed the shore in front of them – the time being summer. Opening the letter which he had taken from the meat-can, he read to his astonished friends:

“Now!” he exclaimed, as he raised the letter aloft; “now, in honor to the men who suffered, and to Lockwood, who perished, the record of their search for the pole shall not rest here, but shall continue its journey, even to the pole itself, and be laid upon the pivotal axis of this mighty globe.”

An hour later the Orion was bearing due north, and the three officers were sitting in the warm cabin discussing the cairn, the letter, and the Greeley expedition of 1880.

Higher and higher rose Polaris to the zenith; onward, mile after mile, flew the ship. The cold outside had become intense, and the spirit thermometer registered 86 degrees F. The aurora filled the heavens about them as if a huge, circular tent of brilliantly colored stripes of fire had been pitched above them. No moisture in the air, no sound, save the whir of the propeller, as it rapidly revolved and sent the vessel forward. Below was ice – ice – and nothing more.

So intense was the cold that, as Cobb unthinkingly touched his bare moist hand to the sextant which had been brought in by the boy, the skin and flesh were burnt as by a red-hot iron.

“It was 18 dial when we left the cairn, in latitude 83 degrees 24 minutes,” said Cobb, after a pause in the conversation, “and the distance to the pole was just 458 miles. Our speed has been uniform, and at the rate of forty-three and-a-half miles per hour, we should cover the distance in ten hours thirty-one minutes and forty-eight seconds, and at thirty-one minutes forty-eight seconds past 4 dial ought to be directly over the pole.”

Indeed, Cobb was perfectly correct in his reckoning, for at the hour mentioned the Orion was brought to a standstill, and then gently dropped to the earth below. Excitedly jumping down the ladders, the three men sprang out upon the snow, and, in one voice, exultingly exclaimed: “The pole! the pole! the north pole!”

True, it was the vicinity of the north pole of the earth, but it was not until after five days of hard work and intricate calculations that the exact spot through which the axis of the earth passed, had been located.

The record showed the exact time of locating this spot to be 12 dial, January 23, 2001.

Then was erected, from such materials as could be spared from the Orion, a monument to mark the spot. A hollow aluminum rod was driven deep through the snow into the earth underneath, and within it were placed letters and papers, and a portion of the documents found in the cairn in latitude 83 degrees 24 minutes.

Their task completed, they contemplated their achievement; a dreary waste, with snow in every direction, contained within its center the evidence of their wonderful discovery; and that evidence was a single monument of boxes, barrels, metals, and whatever else could be spared from the Orion to mark the north point of the earth’s axis! Surely this was little reward for the years of arduous toil and physical suffering of mankind, for the vast sums expended and for the hundreds of human lives which had been sacrificed in the vain ambition of discovering the polar axis of the earth!

The Orion lay about a hundred yards from the monument which had been erected, with her great gas bag nearly empty. A large tent, however, had been set up exactly over the pole to shelter them from the cold winds as they made their observations.

On the morning of the 24th of January the three men proceeded to the tent for the last time. Hugh carried a large box in his arms, and Lester had a storage battery well wrapped in warm flannels.

“It will be gladsome news to your father, Hugh, if you can send a message to him from here,” said Cobb, as they entered the tent.

“Indeed, it will!” joyously returned the other. “I will soon have my instruments in position, and then for word from home!” He beamed with the thought, for might he not hear from Marie? Of course he would! They certainly would tell him where she was, and if she and Mollie were well!

Hugh had brought a set of sympathetic instruments with him, the mate to which was in the office of the President’s private secretary. He had cautioned that gentleman to watch at a certain hour of each day for his signals. That hour had been designated as 11 to 12 dial.

Setting his instruments on the top of the little monument, Hugh worked assiduously to get an answering click from the office in Washington, but without success. In every conceivable position that he laid the needle the result was the same – no influence from its Washington mate. Disgusted, he arose from his work, and debated the situation in his mind.

“Ah!” he suddenly exclaimed, pointing to the needle. “I see it now! The needle is directly over the pole, and moves in the plane of the equator, while every other needle of the whole system of the sympathetic telegraph points to the north star.” As he spoke, he seized the instrument, and carefully turned it on its side until the needle moved in a vertical plane; then fixing it solidly, he brought the needle into a perfectly vertical position, and raised his hands from the instrument.

“Ah!” burst sharp and quick from all. “Click – click – click,” and the needle seemed to fondly pat the little brass stud on its right. “Hurrah! we’ve got him!” cried Hugh, and wild with excitement, he sprang to the key and called, “W-W-W.” Again the joyful click, and the “I-I-I-W” of the Washington operator was heard by all. For an hour the instruments clicked, and message upon message had been sent to the President and others in the great, busy world far to the south of them; and from these messages word had been flashed to all the known nations of the globe of the great success – the discovery of the north pole by three American officers.

At last came the words, through the instrument:

“Your father says Mollie and Marie are in San Francisco yet, and have sent word for you to join them there as soon as possible. They have a surprise in store for Mr. Cobb. He says you are not to delay at the pole, but proceed direct to San Francisco, to your aunt’s. Your father further says that, as Captain Hathaway has made such a record for himself with you and Mr. Cobb, he may call upon him, on his return, in regard to a little matter which has been, heretofore, an unpleasant subject between them.”

Hugh smiled as he translated the message, and looked with a glad expression into the eyes of Lester. That gentleman, as he comprehended the meaning of the message, danced a hornpipe in the snow, and cried, with ecstasy: “She’ll be mine at last!”

“Let us be up and away!” exclaimed Hugh, as he gave the final answers to the Washington operator. “On to San Francisco, Lester! on to our girls, is our cry!”

“Then, take your bearings, Hugh, for Behring Strait,” directed Cobb. “It will be necessary for us to go that way to replenish our supply of lipthalite at Port Clarence, or else trust to the currents part of the way.”

A puzzled expression came over the face of the other, and he seemed lost in a quandary. “Easy enough to say, ‘Take your bearings,’” he returned, “but how? I will be hanged if I know one meridian from another here. In fact, we are on all of them.”

“Don’t you know in which direction south is?” asked Lester, with a laugh.

“Of course, I do. But do you know in which direction the meridian of ten degrees runs, for that is the meridian which passes through Behring Strait?”

In fact, it was quite a puzzling question to answer. All the meridians centered at the pole, and the time there was the apparent time of every meridian on the globe. Standing on the pole, it seemed absolutely impossible for one to know if he were facing London or Washington, or any particular point on the earth’s surface. Hugh scratched his head in perplexity.

“Take the needle,” calmly said Cobb.

“Yes; but it don’t point north any more; it points somewhere south,” he answered.

“And where may that south point be?” inquiringly.

“Why, the north magnetic pole of the earth, of course,” with a glimmer of perception.

“And that pole is where?”

“In Boothia Felix.”

“Exactly; in 70 degrees 6 minutes north latitude, and 96 degrees 50 minutes 45 seconds west longitude, on the west coast of Boothia, facing Ross Straits. Your needle points there; so all you have to do is to lay off 73 degrees 9 minutes 15 seconds to the right, and you have the course to Port Clarence, North Alaska.”

The Orion was again made ready, the gas bag filled, a last adieu given to the north pole of the earth, and the three friends mounted the ladders, touched the electric button of the engines, and sped swiftly down the one hundred and seventieth meridian of longitude.

CHAPTER XXIII

It was the 11th of February, warm and bright, in that delightful climate of California. In the handsome residence of Mrs. Morse, on California street, reclining in a large arm-chair, sat Marie Colchis. A book lay upon the floor, where it had fallen from her hand, and she lay among the cushions with a far-away, dreamy expression in her eyes. Nearly five weeks had elapsed since she left the Island of Guadalupe and came with her two friends to San Francisco.

Care and attention and the best of nursing had saved the girl from the fever which first threatened to make her recovery slow and uncertain. She had regained her health, her flesh and beauty; her skin was exceeding fair, but the whiteness was set off by the rich red of her cheeks and lips.

Recovered from death, among friends who loved her, and expecting every moment the arrival of the one of all men whom she had ever loved, whom she adored now, she lay dreaming of the time when she should be clasped in his arms.

Marie had been informed of everything concerning Junius Cobb. She knew of his apparent infatuation with Mollie, and of his subsequent disinclination for the society of either her or Marie Hathaway. Mollie had told her of the time when he had called her by name in such words of love and endearment, and Marie believed that his heart was hers yet. She was informed of his journey to the pole, of his safe arrival there, and knew that he was expected in San Francisco at any moment.

“Oh that the time would soon come!” she had cried in her heart many times. “Will he know me? Will he still love me?” she had asked herself; “and then, if not, I shall die!” she would murmur sadly, while the beautiful eyes would fill with tears.

“They are coming, Marie! They are coming!” screamed Mollie, rushing into the room. “They are at the door!”

Marie started from her chair, gasped, and pressed her hand to her heart. He was at the door! he whom she loved, and from whom she had been separated for over a hundred years!

“Remember, Marie, your promise; you are Leona Bennett;” and with this parting instruction, Mollie shot to the door just in time to be clasped in the arms of Lester Hathaway, who was leading the way for Cobb. Hugh had stopped in the hall, hugging the plump little form of Marie Hathaway.

A moment later Mollie led Cobb toward Marie, who was standing by the window at the side of the room.

“Leona, this is our friend, Mr. Cobb, of whom you have heard us speak. Junius, my cousin, Leona Bennett.”

Mollie smiled slyly, and gave Marie a knowing look.

Cobb bowed low, and then, looking up, hesitated as if lost in admiration of the beautiful face before him. Ere a word could be spoken by either, Lester and Hugh were brought forward and presented.

“You must have thought me rude, Miss Bennett,” said Cobb, a little later, as he and Marie sat near each other, “not to have expressed the pleasure which I could not but feel at meeting one so beautiful as yourself.”

“I, equally, was unable to more than acknowledge the introduction; for you know the others were upon us, and we had no time,” and she smiled charmingly upon him, while her eyes seemed to have a longing, craving expression. “You have had a most remarkable experience in life, Mr. Cobb,” she added, after a pause.

“Yes,” sadly. “And many times I have wished my fate had ordained it otherwise; but now, Miss Bennett, it would be ungallant, and,” with a searching look, “untrue, to say that I do, for I have met you.”

“Ah, you are like all men, ever ready with a compliment.”

“But it seems as if I was drawn to you by some power I cannot express,” he continued, looking deep into her eyes.

“Do I remind you of some old friend, some old love?” she banteringly asked, though it was easy to perceive that she longed for an affirmative reply.

“That is just what puzzles me, Miss Bennett. It seems as if your face was familiar, and yet I could never have met you before.”

“Are you sure?” She looked up with one of those expressions of childhood days when she had clung to him and begged him to come again to her in Duke’s Lane.

His eyes scanned her; his thoughts traveled back many years. “How like Marie Colchis was that expression,” he said to himself; yet he gave no utterance to his thoughts.

“She was dead, dead long years ago!” Then, aloud, he slowly said: “Yes; I am sure.”

“Then, how can you account for the power of attraction which draws you to me?” she persisted.

“I know not its cause,” he smilingly returned, “unless it be that perhaps all men are similarly attracted. I am but mortal, Miss Bennett, and consequently cannot resist the loadstone of so much grace and loveliness.”

Thus they met, and thus they talked. He knew her not, nor did she reveal her identity. She wished to test the man she loved; and why? Ask a woman!

Two weeks passed, and still they all remained in San Francisco; but the next day was to see them on their way to Washington; the President had sent an imperative summons for all to join him at once.

Junius Cobb had seen Marie every one of these days; had walked and driven and been her escort everywhere. In fact, he had been by her side during every moment that propriety would allow. A new life seemed opened to him; he laughed and chatted like the gayest; he was witty and bright, and the old expression of sorrow had vanished from his face.

He seemed to live in her smiles, to be supremely happy in her presence. He was in love; this time he knew it. Did he ever think of little Marie Colchis? Yes, often and often, and the divinity he now worshiped seemed to him as if risen from the soul of her, and that in loving the former he still maintained his allegiance to the latter. Leona, to him, was his old love Marie. He could not explain the semblance, yet he saw that it existed. He loved Leona Bennett; he thought of Marie Colchis.

Sitting by her side that evening, in the small, cozy library, whither he had gently led her, and whither she had gladly, willingly gone, he quietly said, “Miss Bennett, you return to Washington to-morrow?”

Turning her large blue eyes upon him, she asked, “And do you not go, too, Mr. Cobb?”

“It all depends,” he answered, nervously.

“Why, I thought it was all settled. Mollie told me that you were to go. Have you changed your mind, Mr. Cobb?”

“I dislike to return to Washington,” he continued, not heeding her question, “unless I can do so with a lighter heart than I took away with me when I left.”

“You ought to go there with the greatest pleasure. Your name is famous throughout the world,” and she looked proudly upon him; proud of the man she loved.

“But fame is not all that man craves,” he returned.

“What more can man desire than a name great to the world; a name honored, respected and loved?” Her eyes had dropped, while his were fastened upon her with love intense.

“Love.” He whispered the word lowly and sweetly in her ear as he bent over her drooping form.

Raising her eyes, now full of all that deep love of her aching, patient heart, she met his ardent gaze.

“And can you not have that?” she asked, in tones so low as to be almost inaudible.

“Miss Bennett,” he sadly returned, “mine is a peculiar position. Listen but a moment, and let me tell you my history.”

Junius Cobb then narrated his meeting with Marie Colchis; how he had loved her, but as a child; how he had promised to be her husband, and how he had forsaken her to gratify his ambition. He told her how this love of his little Marie had come to him in all its intensity since his return to life, yet he knew that she was lost to him forever. He informed her of his supposed love for Mollie Craft, and of his sudden discovery that his heart could never be given to her. He related the vision he had wherein Marie had been led to him by an angel. And during all this recital his listener had sat, with tears in her eyes, but a holy feeling of adoration for the man who had remembered her with such love. It was only by a supreme effort that she refrained from declaring herself and falling into the arms of this noble man.

“Miss Bennett – Leona,” gently and slowly; “since my eyes have beheld you, I have seen but one form, have known but one name – Marie Colchis. Yours is the face, the voice, the grace and loveliness that would have been hers at your age. It seems that in your form reposes her soul; that through your eyes beams her sweet and loving nature. Never could two beings be more alike.”

As he spoke the words, Marie’s overflowing heart gave vent to its fullness in a deep sob.

“I know, Leona,” proceeded Cobb, as he noticed her agitation, “that you feel sad at the recital of my story; your great heart – her heart – responds in sympathy to the sufferings of others. I feel that the vision of her coming has been realized; that though departed from this earth and among the angels in heaven, she has sent her soul, her form, her mortal being, back again to earth that I might meet my just reward – life or death. Marie Colchis – for by that name are you henceforth in my heart – I love you, I adore you. Is it to be life or death?”

Amid the sobs which came from her heart, she asked: “And will I always be Marie Colchis to you, Junius? Will you always bear me the love you profess for that other?”

“Yes; a thousand times yes,” he cried, as he arose and took her hand in his. “As my life, will I love you; as my life do I now adore you. O Marie, my darling, my own. Will you give me life? Can you love me in return, for her sake?” pleadingly, as he gently turned the beautiful face toward him and looked into her tear-bedimmed eyes.

Her heart was overflowing; the flood-gates of her love, so long closed and barred, were about to break asunder; her soul had passed out into his keeping. With a passionate cry, she threw her arms about him, and wept tears of joy. Gently he drew her closer to him, and kissed her lips; kissed away the tear-drops in her eyes.

“You love me, my own, my darling!” he cried. “Tell me that you do.”

“O Junius; as I love my God!” Again the tears of joy and happiness flowed fast and furious from her eyes.

“And you reproach me not that I see in you my former love?”

“No. No more is my name Leona Bennett. To you, my own, my noble heart, it shall ever be Marie Colchis. By that name alone shall you henceforth know me, love me, and be my husband.” Thus she spoke the truth, yet kept the promise she had made.

CHAPTER XXIV

“Home again, at last,” gleefully exclaimed Mollie, as the double drag brought the whole party from the depot to the executive mansion.

The President and Mrs. Craft met them at the private entrance, and gave to each a cordial welcome. Marie Colchis was received by the old people as a beloved niece, for Mollie had, in a letter written some weeks before to her father, partially explained the situation of Marie, whom she wished to be called Leona Bennett.

Once in the house, the several members, excepting Mollie, went directly to their rooms to change their traveling clothes; but she, taking her father by the hand, asked him and her mother to give her a few moments of their time, as she had something of importance to relate. Once in the library, she knelt at her father’s feet, and related the whole story concerning Marie Colchis. She told of finding the letter in Cobb’s room, and of her journey to Guadalupe Island, and the rescue of the girl; she dwelt upon all the wonderful incidents of the finding of the cavern and its contents; and then she told him of the letter which was found with Marie, and the relations which had existed between Marie and Junius Cobb, years ago; that Junius was ignorant of Marie’s identity, but was in love with her, and had asked her to marry him.

The iron box which was found in the cavern, and which was now in the trunk, was next spoken of. Finally, she admitted to her parents her love for Lester, and his adoration of her, and asked for their consent to their union. “And this is not all, dear papa and mamma,” she said: “Marie Colchester is Marie Hathaway, Lester’s sister; I brought her here to win the love of Junius, but it was not to be, for” – and she hesitated – “for she is engaged to Hugh.”

It was several minutes ere Mr. and Mrs. Craft could grasp the whole situation, the revelations had come so fast and free; but, finally, the old man took his wife’s hand in his, and slowly, but with a smile of pleasure, said: “Mamma, we were young once.”

Mollie accepted the words and expression of his face as evidence that a happy termination would end the hide-and-seek courtship of herself and Lester; she kissed them both, and ran to communicate the good news to her lover.

It was evening of that day. A happy, jolly, bright party was congregated in the private parlor of the executive mansion. In the corner, by the great mirror, sat Junius Cobb and Marie Colchis, his eyes drinking in the beauty of her being, and his thoughts wrapped in a contemplation of her grace and loveliness. On the sofa, across from them, sat Hugh and Marie Hathaway; Lester was alone in a big arm-chair near the window, while Mollie stood in the center of the room under the electric lights, bright, radiant and vivacious.

“Three spooney couples!” she cried. “No; I mean two and a half – and you are the half, Lester,” slyly turning her head toward him. “Six hearts beating as one; all in unison, but none engaged. He is coming, papa is coming; and I advise some young gentlemen whom I could name to step boldly to the front and ask – well, I think I’ll say no more, but I pity you. Papa holds his daughters in an iron fist,” and she clenched her little hand to emphasize her words.

A moment later and the President and his wife entered the room, and all arose to meet them.

“Be seated, my children,” he kindly said. “For the first time in my life I feel that I have three beautiful daughters and three noble sons. I have asked you to meet me here that I might bring complete happiness to three pairs of loving hearts. I know all your secrets, dear children; everything is known to me.”