полная версия

полная версияA. D. 2000

“I cannot tell you much, Junius, for I am not well posted on the subject. These transatlantic life-stations are set on a line extending from St. John’s, Newfoundland, to Land’s End, England, or nearly on the fiftieth parallel of north latitude. Perhaps there may be something relating to the subject among the books in the chart-room. Excuse me but a moment, and I will look.” Saying which, he arose and passed out to the pilot’s house. A moment later he returned, bearing a pamphlet in his hand.

“Here we are, my boy,” he exclaimed, as he shut the door behind him. “Here’s quite a history of these stations. I found it among the nautical almanacs and charts in the pilot’s room.”

Opening the first page, Hugh displayed three wood-cuts of one of the transatlantic life-stations. The first cut showed the station in its normal position upon the surface of the ocean; the second showed it partially submerged, during a storm, and the third gave a cross-section of its interior. Handing the book to Cobb, he said: “You can read it yourself, for everything is explained therein, I think.” The other took the pamphlet, and settling himself back in his chair, read of this wonderful adjunct to a safe traveling of the great Atlantic highway to Europe.

There were, across the Atlantic Ocean, from Newfoundland to England, thirty-eight marine life-saving stations. These stations were, in all respects, similar; a full description of one answered for all. In the pamphlet which Cobb read, were given the details of Station No. 14, situated in longitude 37 degrees 5 minutes west, and latitude 49 degrees 50 minutes north. He read:

“HISTORY OF THE TRANSATLANTIC LIFE-SAVING SERVICE“In 1923 a joint commission of Great Britain, France and the United States, met in the city of Washington for the purpose of devising some means toward making travel across the Atlantic Ocean more safe and sure than was possible under the circumstances at the time. Vessels of the finest description and of great tonnage were traversing a well-known route continuously. Accidents had occurred, which it seemed could not have been prevented, whereby a great number of lives had been sacrificed and vast property lost.

“Great factors in the calling together of this commission were a series of terrible accidents in the years 1919, 1920, and in the fall of 1922.

“On the 15th of July, 1919, at 23 dial, or as they then reckoned time, 11 o’clock P. M., the City of New York was struck by lightning, in latitude 49 degrees 10 minutes, and longitude 31 degrees 14 minutes. Despite the endeavors of a well-trained crew and every facility for extinguishing fire, the vessel burned and sunk; 2,167 souls who were aboard of her at the time took to the boats. Of this number 914 only were rescued, or ever heard of. Those who were rescued had sailed over 450 miles before being picked up. The supposition is that the distance from land was too great for them to overcome with the limited amount of water and food aboard the boats, and had land, or some station, been within reasonable distance from the scene of the accident, all would have been saved.

“A most peculiar case was that of the City of Providence in 1920. This vessel was one of the finest of the American transatlantic passenger steamers, 600 feet in length, with a tonnage of 16,000. She left the Mersey on October 7 of that year, with 3,465 souls on board. On the morning of the 9th, at 4:12 dial, a terrible accident occurred; two of the thirty-six boilers burst, the concussion causing nine more to explode. The vessel was torn almost asunder, her bulkheads broken, and the water poured into the ship. Her engines were wrecked, and the engine-room flooded. A vessel of ordinary construction would have sunk immediately, but the Providence, having every improvement, and a great number of water-tight compartments, continued to float. Torn and broken, she lay upon the ocean perfectly helpless.

“The strange but sad continuation of this disaster follows:

“The City of Providence, making the trip across the ocean, as she usually did, in four days, carried provisions for but eight days. After the explosion the ship drifted at the mercy of the currents and wind.

“It was four weeks after the disaster when she was found by vessels sent out to look for her, in latitude 44 degrees 12 minutes, and longitude 31 degrees 16 minutes. Seven boats’ crews had left her to seek aid; her passengers had been cut down to rations, and finally every vestige of food had been consumed, and starvation and thirst commenced their deadly work. Out of that host of people on the Providence when she sailed, only fifty-four lived to tell of the terrible disaster. Four of the boats were never heard from, and only twenty-seven persons were found alive on the ship. During all these weeks that the Providence drifted about, she twice crossed the line upon which the life-stations are now situated. Had these stations then been in existence, every soul on board of the ill-fated vessel would probably have been saved. How it could be that a vessel of the Providence’s size could have escaped the notice of the hundreds of ships passing in that latitude is a problem none can solve; that she did, is a fact, for no report of her was ever made until she was sighted by the relief vessel sent out to search for her.

******“These terrible disasters, taken in consideration with the great advantages which would accrue were there stations at intervals across the ocean, led to the creation of the commission.

“The commission met on the 19th day of June, 1923, and made proposals for plans for these stations. On the 11th of December of that year the commission selected, from the plans submitted, those of Mr. Cyril Louis, of California.

“These plans were for a huge cylindrical vessel, sitting upright in the water, and surmounted by a tower one hundred feet above the water line. The vessel proper was a cylinder; its base, a plane; its top, the frustum of a cone, surmounted by a tower upon a tower. The cylinder was eighty-three feet in length to the water line, the cone nine feet high, the first tower fifty one feet above the frustum of the cone, and the second tower forty feet above this. The cylinder was made of boiler iron in three layers of one-inch plates, and covered on the outside with aluminum plates a quarter of an inch thick; the diameter was thirty feet, and the vessel was divided into eight stories by floors of one-inch steel. The first, or lower, and second chambers were fourteen feet high; the next twelve; the four following, ten; while the top chamber, under the cone, was twelve feet to the frustum. All of these chambers, except the first, were divided into water-tight compartments by steel bulkheads. The second chamber had eight compartments; the third, two; the fourth, fifth and sixth, four; the seventh and eighth two. The first, or main tower extended down through the cylinder to the top of the third chamber, and was eight feet in diameter. It was necessary to pass through this tube to gain entrance to any of the floors. Access to the different compartments of each floor was by means of doors closing water-tight. The chambers were for use as follows: the first contained 10,000 cubic feet of fine sand – 1,300,000 pounds – or so much of it as was needed to bring the surface of the water to within three feet of the cone. This chamber was peculiarly constructed; water-holes permitted free access to the surrounding water, causing the sand to be saturated. Ten capped openings in the bottom were manipulated from the engine-room and office, and by means of which any amount of sand could be quickly dropped from the chamber into the ocean, thus decreasing the weight and increasing the buoyancy.

“The second chamber was the water-chamber, and was divided into eight separate compartments. Water could be admitted into any one, or all, by suitable levers worked in the engine-room. Pipes from each compartment were connected to the pumps in the engine-room, thus permitting of the compartment being quickly emptied of its water. The capacity of the eight compartments was 10,000 cubic feet, or 64,000 pounds of water.

“The third chamber was the engine-room. Here was all of the machinery used in operating the station: The main engines for the pumps (pipes from which ran to every compartment in the cylinder), for the fans for circulating fresh air; dynamos for electric lighting, pumps of the condensers, and, last, the three propellers, which were situated on the outside, on a level with the engine-room floor – two at 180 degrees apart, their faces parallel to the diameter of the cylinder, and the other at right angles to them and ninety degrees from either. These propellers were used to prevent any rotary motion of the cylinder.

“Until lipthalite had been discovered – and it is now used – petroleum was the fuel for these engines, the vapors escaping through a tube extending to near the top of the first tower. Within the engine-room was a set of dials and bells which would give instant warning of the entrance of water into any compartment, tubes and telephones to all parts of the vessel; dials for pressure, submergence, state of electricity; levers for opening sand and water ports, etc. The fourth and fifth chambers were for stores and material.

“The sixth contained the kitchen, mess, etc.

“The seventh was the dormitory, while the eighth was the officers’ cabin and office. Natural light was admitted into the last two chambers through bull’s-eyes.

“The office was provided with every instrument necessary in operating the station, and from it the sand and water ports could be opened.

“The first tower was eight feet in diameter, tapering to five feet at the top, and fifty-one feet high. It was made of two-inch steel rings, six feet wide, firmly riveted together, the whole covered by aluminum plates.

“The entrance to the vessel was through the tower, at the top of the frustum. A spiral stairway led to a port at the top, through which the upper balcony was reached. Bull’s-eyes admitted light to the interior during the day.

“The upper tower was forty feet high in the clear, setting down fifteen feet in the first tower, and was twenty inches in diameter, of one-inch cast steel. The interior of this tower was divided into a central pipe of ten inches diameter, surrounded by four pipes in the quadrants of its area. The central pipe was used for raising the electric lamp, of 25,000 candle power; the other pipes were, two for the engines, to carry off the vapors, etc., one for receiving fresh air into the vessel, and the other for carrying off the vitiated air.

“Upon the side of the cone was a complete life raft, provisioned and ready for instant use, and so fastened that it could be launched at a moment’s notice.

“The station was anchored by a three-inch cable, pivoted at both ends to prevent twisting. In the center of the cable were electric wires terminating at the bottom of the ocean in a large coil. This coil was laid upon one of the old Atlantic cables which had been abandoned after the invention of the sympathetic telegraph.

“In the office were a set of instruments, and communication was by induction to the cable below, and thence to each end and to each station.

“The normal submergence of the vessel was to within three feet of the cone. The exceptional, or rough weather, submergence was to within two feet of the top of the tower.

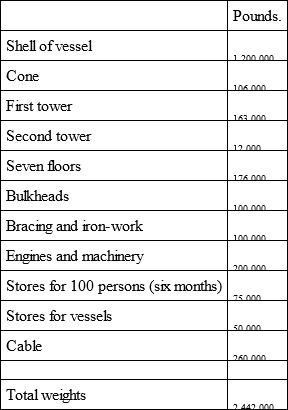

“The weights were as follows:

“The normal displacement of the vessel was 57,225 cubic feet, or 3,664,000 pounds. This displacement, less the weights, gave an excess of 1,200,000 pounds, which was compensated for by the sand in the sand-chamber – the capacity of that chamber being 1,300,000 pounds.

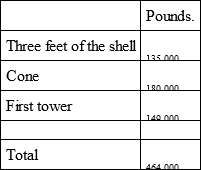

“During stormy and rough weather, to decrease the pressure of the winds and waves upon the towers, and to increase the stability of the vessel, water could be admitted into the water-chambers, and the vessel would sink until the water line was within two feet of the top of the first tower, for the displacements to be overcome were:

“The capacity of the water-chamber being 677,000 pounds, there was a large excess over this displacement; this excess was to compensate for loss of weight by stores being used, taken out, etc.

******“The station carries a flag at its peak, by day, with its station number thereon; at night it shows a 25,000 candle-power light; its interior, also, is lighted by electricity.

******“The plans of Mr. Louis were accepted, and in less than three years a line of thirty-eight stations were placed across the Atlantic Ocean.

******“It was agreed between the nations that each should contribute a third of the cost ($12,000,000), and that salvage for person and property, at a fixed and just rate, should be demanded from every nation whose flag may be succored by one of these stations; and further, that should war intervene between any of the nations contracting, the line of stations should remain unmolested, and should not be used for purposes of war.”

Cobb dropped the pamphlet by his side, and pondered over the great invention of which he had just read, and which he had seen.

“And have no accidents ever happened to these stations from ice-floes, collisions, or faulty construction?” he finally asked, turning toward Hugh.

“I believe there has been but one noteworthy accident,” the other returned. “An immense ice-floe caused Station No. 5 to slip her cable, and run away – an easy matter for her, as her propellers give her a speed of about five miles an hour. Of course her cable was lost; but she was saved, and was picked up and reset by the lipthalener which continuously plies along the line.”

It was now nearly 23 dial, and Cobb arose, and consulted the speed dial of the Orion.

“Hugh,” he said, “please have the course changed to due north; we are nearly on the fortieth meridian, and should now make direct for Cape Farewell.”

The other passed up to the pilot’s house.

CHAPTER XXII

The cold was increasing, and the snug, warm cabin of the Orion was a most acceptable substitute for the frost-covered deck of the vessel. At 7 dial breakfast was laid, and the three officers partook of a hearty meal; then lighting their cigars – the necessity for fires aboard the vessel being removed by the substitution of meteorlene for hydrogen – they lay back and enjoyed the hour.

“Why did you bring so much meteorite and acid?” suddenly asked Lester.

“Because,” answered Cobb, “I wished to have enough to meet all emergencies which may arise. I have enough to fully inflate the balloon four times.”

“Do you intend to make direct for the pole from Cape Farewell?” broke in Hugh.

“No. I wish to satisfy myself about the northern extremity of Smith’s Sound first. I shall pass west when on the eightieth parallel of latitude.”

“Can you explain why it is that the pole has never been reached by land parties?” inquired Lester.

“My opinion,” replied Cobb, “is that they have never proceeded upon the proper course. I think that Smith’s Sound leads the waters of an immense polar ocean into Baffin’s Bay; that the sea is a moving sea of ice, and that any northward progress upon it would be more than counterbalanced by its southward movement. I have long believed that the only route lay along the backbone of Greenland.”

“Well,” with satisfaction, “we can soon ascertain the truth or fallacy of your hypothesis,” exclaimed Hugh.

“Yes; for we will pass up on the fortieth meridian of longitude to the eightieth parallel; this course will take us over the central length of Greenland,” and Cobb blew a cloud of smoke about him, and closed his eyes in meditation.

At precisely 4:15 dial the following day the Orion stood poised above the southern extremity of Greenland. The earth below them lay like a white sheet, extending as far to the north as the eye could reach; the waters to the south were covered with floating ice, while great, towering icebergs were visible in many directions. The cold had become very great, and it was necessary to change their clothing for fur. But, despite the freezing atmosphere, they were warm and cozy in the ship. Hugh had worked hard during the two days given him to complete their arrangements; the canvas exterior of the car had been given a thorough coating of heavy varnish, and the interior lined with blankets throughout, while heavy, thick carpets covered all the floors. The electric heaters, except in the pilot’s house and three staterooms, had been replaced by oil-stoves of superior heating properties. Ten barrels of oil had been placed on board, and one hundred cells of storage battery added to the plant. With these wise provisions and the forethought to provide an abundance of the warmest flannel, and fur clothing for all, the severity of the weather had little effect upon the welfare and comfort of those aboard the Orion.

A strong wind was blowing off the coast, and the vessel made but little headway; the barometer marked 26.64 inches, and the elevation was 3,200 feet.

“Lester,” said Cobb, after a pause, and looking through the frosted window, “I wish you would increase the gas; we must rise above this current of air, or we will be blown off the coast.”

Hathaway passed out, and filled the receivers, and soon the Orion was rapidly ascending. Watching the barometer carefully, Cobb soon put his lips to the speaking-tube, and called to Lester: “That will do.” The barometer registered 18.2 inches, and the elevation had been increased to 13,000 feet, striking a strong current which immediately took the vessel swiftly due north.

Cape Farewell was in latitude sixty degrees, and on the forty-fourth meridian from Greenwich. It was over 1,200 miles to the eightieth degree, from which Cobb intended to move west to Smith’s Sound.

The days had become shorter and shorter as they progressed northward.

“It’s a bad time of the year,” said Hugh, “to make the voyage. The cold will be intense, and there will be no sun north of the seventy-fourth degree after to-day.”

“Yes; I know it,” returned Cobb. “But we will have the aurora, and that will give a sufficiency of light for all our purposes.”

In the steady, strong northerly current, the Orion made rapid progress. The great glaciers of Southern Greenland were passed, and then the chain of mountains which traverses the land from north to south were reached. Keeping exactly along the backbone of the range, the Orion sped northward.

On either side great canyons opened toward the west and east; immense rivers of ice and slow-moving glaciers extended toward the sea. The land was white with snow, save here and there where the black rocks of the mountains broke through. A barren, dreary waste was upon every side, and a scene of utter desolation presented itself to these few mortals far up in the clouds.

Still the vessel moved northward; degree after degree was passed, and it was 12 dial when they reached the seventy-fifth degree of latitude. The sun lay like a ball of fire upon the plain of snow to the south, its disc just visible as it seemed to rest on the horizon. The three officers stood at the rail, and raised their fur caps in salutation.

“Good-bye, old Sol; good-bye to your bright light!” cried Cobb, as he waved his cap. “It will be many an hour – days, even, and perhaps years, ere your face is seen by us again!”

“Let us say days only, Junius,” the others exclaimed, together. “We hope soon to see its glorious face again.”

“Perhaps!” With this single word, Cobb turned and entered the cabin, where he spread out before him a chart of the arctic regions, and examined it intently. Five degrees more and he would turn to the west!

Dinner was soon announced, and eaten with a relish, as the bracing air had given each a good appetite. The sunlight had given place to twilight, and that, in turn, had been followed by night. The stars shone out with brilliancy, and studded the heavens in every direction. The Orion, being in an upper current, moved with surprising evenness. The pole-star was high in the sky, and the great bear directly over their heads.

It was 18 dial by their chronometers, and they should be near the eightieth parallel.

“Hugh,” said Cobb, rising from his chair, “will you take the latitude from Polaris? Never mind the refraction; I want it only to within a few minutes.” Hugh took the sextant, and left the cabin, while Cobb turned to Hathaway, and remarked: “Lester, this is a very comfortable room, this one of ours in the arctic regions, is it not?”

“Indeed, it is,” the other replied.

“And we are going north, to the extremity of the earth?”

“I understand such to be your intention.”

“It would be sad for you and Hugh if we never returned!”

“I do not think of it in that light,” smilingly returned his companion, as he lighted a fresh cigar. “There is no reason why we should not return, and return in a halo of glory.”

“I hope so.”

At this moment Hugh came, and announced that he made the latitude 79 degrees 55 minutes. Seven minutes later the course of the Orion was laid due west.

On the 17th of January, at 1 dial, the vessel lay to over Napoleon Island. From this point they proceeded due north, Cobb carefully watching the earth below them. For three degrees the course of Smith’s Sound was plainly visible, then it terminated in a great sea of floating ice to the north. “As I thought,” he murmured: “There is no road to the pole from the continent of North America.”

At 6 dial the Orion’s course was still due north.

Returning to the cabin, breakfast was served, and all enjoyed the good things which had been prepared, and, also, the warmth of the interior. As the hour of 10 dial drew near, Cobb took the sextant, and passed out of the cabin, and stationed himself at the rail near the pilot’s house. There, with instrument in hand, he carefully watched Polaris rise toward the zenith as the ship moved north. Suddenly he dropped the instrument to his side, and cried, in a quick, sharp voice: “Ninety degrees to the right; quick!”

The Orion turned in a graceful curve, and bore due east.

At 16 dial Cobb again came on deck and consulted his sextant. After a moment he laid aside the instrument, and took his watch in his fur-covered hand, and noted the revolution-counter on the side of the pilot’s house. “We are moving due east on the parallel of 83 degrees 24 minutes,” he replied to Hugh and Lester, as the two men came from the cabin and inquired why he was consulting his watch, “and if I am not mistaken, will be on the meridian of 40 degrees 46 minutes in five minutes,” and he put the telescope to his eye and intently examined the earth below them. “Ha! As I thought!” he suddenly cried, excitedly: “Stop her! Stop her! Stop the engines!”

The pilot threw over the electric switch, and the great propeller gradually ceased to revolve. Jumping quickly to the escape-valve, Cobb carefully allowed the gas to escape, and the Orion began gently to settle. Hugh and Lester looked at the man in amazement. Was he crazy? Why was he thus descending into a barren, icy plain miles yet from the pole?

“Make ready, Hugh, to alight,” cried Cobb. “I will explain all afterward.”

The Orion touched the snowy plain. Still discharging gas that the vessel might not ascend, when relieved of the weight of himself and companions, he pointed to a cone of rocks standing high and bare above the snow, some four hundred yards away.

“That is why I have landed,” he quietly said: “Come; follow me, and I will explain.”

Stepping down the ladders, the three men made their way over the snow toward the spot pointed out, and found a pile of rocks about thirty feet high standing on the shore of the icy sea. As Lester and Hugh examined the monument, Cobb, saying nothing, commenced to pull aside the stones. A moment later and he had unearthed an old rusty meat-can, and was excitedly tearing it open. Its contents was a letter. Without waiting to hear the questions which he knew the two men were about to ask, he said: “This is the cairn left by Brainard and Lockwood in 1882. This is the spot, 83 degrees 24 minutes north latitude, and 40 degrees 46 minutes west longitude, which they reached on that day, memorable in history, when the highest latitude on the globe was reached by a human being.”