полная версия

полная версияPastoral Days; or, Memories of a New England Year

Now comes an open level, with wide, expansive views, where every turn upon the road brings its fresh surprise, as some new combination of hazy mountain landscape towers above the distant river bend; and the flitting cloud shadows lead their capricious, undulating chase across the wooded slopes. The roadsides here are full of everchanging beauties too, with their trimmings of ornamental sunflowers, their picturesque old fences, and their clumps of purple-berried poke-weed, with here and there a yellow patch of toad-flax, and aromatic tufts of tansy hugging close against the fence. Even that clambering screen of clematis that trails over the shrubbery yonder cannot hide the scattered tips of crimson that already have appeared among the sumach leaves.

There are a thousand things one meets upon a country ride or ramble which at the time are allowed to pass with but a glance. The eye is surfeited and the mind confused with the continual pageantry. But months afterward, in the reveries about our winter fires, they all come back to us, with the added charm of reminiscence; and whether it be a crystal spring among a bank of ferns, or a thistle-top with its fluttering butterfly and inevitable bumblebee rolling in the tufted blossom, or a squirrel running along a rail, or perhaps a rattling grasshopper hovering in mid-air above the dusty road – no matter what, they all are welcome memories at our fireside, and draw our hearts still closer to the loveliness of nature.

This Housatonic road is rich in just such pastoral pictures. Two hours on such a course soon pass, when our pony whinnies at the welcome sight of the old log water-trough beyond – a landmark old and green when I was yet a boy, still nestling in its rocky bed, shadowed by the drooping hemlocks, still lavish with its overflowing bounty.

This benefactor by the way-side marks a turning-point in our journey, as we leave the grandeur of the Housatonic to pursue our way by the nooks and dingles of the wild Shepaug – a bubbling tributary whose happy waters sing of a varied experience. Now placid through the blossoming fields, now plunging down the precipice to ripple through a verdant valley, where, hemmed in at every turn, it seeks its only liberty beneath the rumbling of the old mill-wheels; and at last, ere it loses its identity in the swelling tide, leaving a mischievous and tumultuous record as it pours through the rocky cañon, and with surging, whirling volume carves huge caverns and fantastic statues in its massive bed of stone. Even now through the dark forest beyond we can hear the muffled roar, and for nearly a league farther as we ascend the long hill it comes to us in fitful whispers wafted on the changing breeze. Reaching the summit of this incline, we find ourselves on a hill-top wide and far-reaching, on right and left losing itself in wooded wold, while in front the level road diminishes to a point, surmounted by blue hills in the distance. Two miles on a pastoral hill-top, where golden-rod and tall spiræas cluster along the lichen-covered walls, where orange-lilies gleam among the alders, with now and then a blazing group of butterfly-plant or a dusty clump of milk-weed. The air is laden with the nut-like odor of the everlasting flowers all around us. The buzzing drum of the harvest-fly vibrates from every tree, and we hear the tinkling bell and lowing of the cattle in some neighboring field. Farther on, we look down from the edge of the plateau through the length of Happy Valley, with its winding stream, its barns and busy mills, its sunny homes glinting through the summer haze. On the left the lofty shadowed cliff known as “Steep-rock” towers against the evening sky, and again we catch the murmuring whiffs of the rushing stream in its sweeping bend beneath the overhanging precipice. A sharp turn round a jutting hill-side, and I meet a prospect that quickens the heart and makes the eye grow dim. There beyond, three miles “as flies the laden bee,” I linger on the welcome sight, as on its hill-top fair two steeples side by side betray the hidden town, my second home.

How lightly did I appreciate the fortunate journey when, twenty summers ago, I followed this road for the first time, when a boy of ten years, on my way to an unknown village, I looked across the landscape to the little spires on that distant hill! Little did I dream of the six years of unmixed happiness and precious experience that awaited me in that little Judea! I only knew that I was sadly quitting a happy home on my way to “boarding-school” – a school called the Snuggery, taught by a Mr. Snug, in a little village named Snug Hamlet, about twenty miles from Hometown.

There are some experiences in the life of every one which, however truthful, cannot be told but to elicit the doubtful nod or the warning finger of incredulity. They were such experiences as these, however, that made up the sum of my early life in that happy refuge called in modern parlance a “boarding-school” – a name as empty, a word as weak and tame in its significance, as poverty itself; no doubt abundantly expressive in its ordinary application, but here it is a mockery and a satire. This is not a “boarding-school;” it is a household, whose memories moisten the eye and stir the soul; to which its scattered members through the fleeting years look back as to a neglected home, with father and mother dear, whom they long once more to meet as in the tenderness of boyhood days; a cherished remembrance which, like the “house upon a hill, cannot be hid,” but sends abroad its light unto many hearts who in those early days sought the loving shelter; a bright star in the horizon of the past, a glow that ne’er grows dim, but only kindles and brightens with the flood of years. Yes, yes; I know it sounds like a dash of sentiment, but words of mine are feeble and impotent indeed when sought for the expression of an attachment so fond, of a love so deep.

Fifteen years ago, with a parting full of sorrow, I rode away from Snug Hamlet yonder in the village stage – a day that brought a depression that lingered long, and lingers still. Glowing, sunset-tinted fields glide by unnoticed now, as, with eyes intent on the distant hill, I look back through the lapse of time. A mile has gone without my knowing it, when a joyous laugh awakens me from my day-dreams. Two boys approach us on the road ahead, and, what might seem very strange to you, one wears a wooden boot-jack strung around his neck and dangling on his breast; but he carries his burden lightly and cheerfully. As they near the carriage I draw the rein, and they both pause by the roadside.

“Well, boys,” I ask, “where do you hail from?”

“We’re from the Snuggery, sir.”

“I thought so,” said I, with a laugh, in which they both joined. “But what are you doing with that boot-jack?”

“Oh, you see,” said one, with a roguish smile, “Charlie and I were having a little tussle in the sitting-room, and he picked up Mr. Snug’s boot-jack in the corner and began to pummel me with it; and jest as we were having it the worst, and were rollin’ on the floor, Mr. Snug came in and caught us in the job, and now we’re payin’ for it.”

“How so?” I inquired, well knowing what would be the response.

“Oh, you see, Mr. Snug held a diagnosis over our remains, and said he thought we were suffering, for the want of a little exercise, and ordered us on a trip to Judd’s Bridge.”

“And the boot-jack?”

“Oh, he said that Charlie might want to play with that some more on the way, and that he’d better fetch it along;” and with a mischievous snicker at his encumbered companion, he led him along the road in an hilarious race, while we enjoyed a hearty laugh at their expense.

And this a punishment! Yes, here is an introduction to one phase of a system of correction as unique as the matchless institution in which it had its birth – a system without a parallel in the annals of chastisement or school government, and which for thirty years has proved its wisdom in the household management of the Snuggery.

“To Judd’s Bridge!” How natural the sound of those words! How many times have I myself been on that same pilgrimage of penance! The destination of these boys is a rickety but picturesque structure which spans the Shepaug five miles below Snug Hamlet. Through three decades it looks back to its host of acquaintances of those romping lads who, in the superfluity of exuberant spirits, made havoc and din in the household. The dose is administered with wise discrimination both as to the symptoms and the needs and strength of the patient. It always proves a sterling remedy, and sometimes, indeed, a sugar-coated one, as in the case of these two ruddy, rollicking examples.

Judd’s Bridge is but one of a score of places which serve in the administration of Snuggery discipline. It is, however, the one most remote, and its ten-mile journey is reserved as an heroic dose for extraordinary cases, after other prescriptions have been tried without avail. Next on the list comes Moody Barn, with “open doors” every day in the week to its frequent callers. This old settler, gray and weather-beaten, marks a point one mile from the Snuggery, where the still waters of the Shepaug run slow and deep – the favorite “swimming-hole” of the Snuggery.

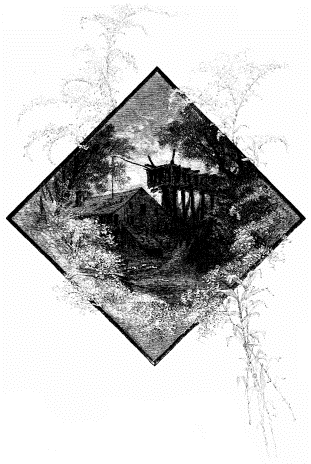

THE HAUNTED MILL.

And then there’s Kirby Corners, a mere stroll of a few minutes round the square of a rock-bound pasture – just enough to give yourself time to think a bit and congratulate yourself on what you have escaped. All these, and several more, are vivid in my memory; friends, old and intimate. And here’s another, right before us by the roadside. For several minutes through the tantalizing trees we have heard its rumbling wheel, its reiterating clank, and busy saw; and now, as its familiar outline looms up against the evening sky, the vision seems to darken, as on that night of long ago, when through the shadowy mystery of the moonlit gloom I stole my way among the sheltering golden-rod; when the lofty flume, like a huge horned creature, seemed to stride athwart me in the darkness, and the fitful boyish fancy saw strange phantoms in the floating, melting mist. This ancient structure reposes in a verdant dell at the foot of Snug Hamlet Hill. A choice of two roads lies before us – one short and direct, the other a roundabout approach. A sudden impulse leads me into the latter. On right and left I see the same old rocks and trees. There stands the aged beech to whose gnarled and hollow trunk I traced the agile flying-squirrel, and with suffocating flame and smoke drove him from his hiding-place. Here between large rocks and stones the trout-stream runs its course, now pouring in small cataracts, now eddying into still, dark nooks, where in those by-gone times I dropped the line of expectancy, but showed the clumsiness of adversity. A few minutes later, and we are gliding again by the dark Shepaug, now flowing calm and silent beneath a rugged bank, wild and umbrageous, where the swarm of katydids, with grating discord, maintain their old dispute, that never-ending feud. The wheels turn noiselessly in the shifting sand as we pursue our way. The low gray fog steals lightly over the lily-pads, floating into seclusion beneath the sheltering boughs, or, like an evanescent spirit, borne upon the evening breath, is lifted from the gloom, and slowly melts into the twilight sky. The solitary whippoorwill from his mysterious haunt, perhaps in yonder tree, perhaps in the mountain loneliness beyond, proclaims with dismal cry his oft-repeated wail. And as we ascend the darkening path, through the still night air, in measured cadence long and sad, we hear the toll of the distant knell. Threescore-and-ten its numbers tell of the earthly years – a curfew requiem for the dead. Even as we pass the little chapel at the summit of the hill, and the bell has scarcely ceased its melancholy tidings, we hear the shouts and merry laughs of the boys on the village green. Presently its broad expanse, shut in by twinkling windows and massive trees, spreads out before us, as a clear and ringing voice, like that of old, echoes through the growing darkness, “One hundred! Nothing said, coming ahead!” and a dim figure steals cautiously from the steps of the old white church to seek in the sequestered hiding-places. With a heart that fairly thumps, I urge my pony onward across the green, and ere he slackens his pace I am at my journey’s end. The dear old Snuggery, with its gables manifold and quaint, its fantastic wings and towers, stands there before me, the glowing windows beaming through the maples. Leaving our pony in willing hands, we enter the gate, and are soon upon the wide porch.

PURSUERS AND PURSUED.

It is eight o’clock, and the Snuggery is hushed in the quiet of the study hour, and as we look through the windows we see the little groups of studious lads bending over their books. Turning a corner on the piazza, we are confronted with a tall hexagonal structure at its farther end. This is the Tower, the lower room of which is consecrated to the cosy retirement of Mr. and Mrs. Snug. The door leading to the porch is open, and, as if awakening from a nap in which the past fifteen years have been a dream, I listen to the same dear voice. I approach nearer. Under the glow of a student’s lamp I look upon the beloved face, the flowing hair and beard now silvered with the lapse of years – a face of unusual firmness, but whose every line marks the expression of a tender, loving nature, and of a large and noble heart. Near him another sits – a helpmeet kind and true, cherished companion in a happy, useful life. Into her lap a nestling lad has climbed; and as she strokes the curly head and looks into the chubby face, I see the same expression as of old, the same motherly tenderness and love beaming from the large gray eyes.

Mr. Snug is leaning back in his easy-chair, and two boys are standing up before him; one of them is speaking, evidently in answer to a question.

“I called him a galoot, sir.”

“You called George a galoot, and then he threw the base-ball club at you – is that it?”

“Yes, sir,” interrupted George; “but I was only playing, sir.”

“Yes,” resumed the voice of Mr. Snug, “but that club went with considerable force, and landed over the fence, and made havoc in Deacon Farish’s onion-bed; and that reminds me that the deacon’s onion-bed is overrun with weeds. Now, Willie,” continued Mr. Snug, after a moment’s hesitation, with eyes closed, and head thrown back against the chair, “Saturday morning – to-morrow, that is – directly after breakfast, you go out into the grove and call names to the big rock for half an hour. Don’t stop to take breath; and don’t call the same name twice. Your vocabulary will easily stand the drain. You understand?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And, George,” continued Mr. Snug, with deliberate, easy intonation, “to-morrow morning, at the same time, you present yourself politely to Deacon Farish, tell him that I sent you, and ask him to escort you to his onion-bed. After which you will go carefully to work and pull out all the weeds. You understand, sir?”

“Yes, sir.”

“And then you will both report to me as usual.” And with a pleasant smile, which was reflected in both their faces, the erring youngsters were dismissed. Before the door has closed behind them we are standing in the door-way. Here I draw the curtain; for who but one of its own household could understand a welcome at the Snuggery?

Those of my old school-mates who read this meagre sketch will know the happiness of such a meeting; but others less fortunate in the recollections of school-life can only look for its counterpart in an affectionate welcome in their own homes, for the Snuggery is a home to all who ever dwelt within its gates. Seated in the familiar cosiness, and surrounded by the friends of my school-days, the hours fly fast and pleasantly. There is plenty to talk about. Here is a village full of good people of whom I wish to learn, and there are many far-off chums of whom I carry tidings. A bell rings in the cupola as one by one, from the buzz in the outer rooms, boys large and small seek our seclusion for the accustomed good-night adieu; and ere another hour has passed forty sleepy urchins are packed away in their snug quarters. The evening runs on into midnight, as with stories of the past, its pains and penalties, its remembrances, now humorous now sad by turns, we recall the good old times; and the “wee sma’ hours” are already upon us as we reluctantly retire from the goodly company to our rooms across the way.

TOLLING FOR THE DEAD.

The next morning finds us in the midst of a merry load, with Mr. Snug as a driver; and many and varied were the beauties that opened up before us on that charming ride! Snug Hamlet, once called Judea, in the qualities of its landscape as well as in everything else, is unique. Stripped of all its old associations, it presents to the artistic eye a combination of attractions scarcely to be equalled in the boundaries of New England. Situated itself on the brow of an abrupt hill, where its picturesque homes cluster about a broad open green, a few minutes’ drive in any direction reveals a surrounding panorama of the rarest loveliness. Five hundred feet below us, winding in and out, now beneath leafy tangles, now under quaint little bridges, and again reposing placidly in broad mill-ponds, the happy Shepaug lends to a lovely valley its usefulness and beauty. Turning in another direction, we pass the Snuggery ball-ground, animated with the shouts of victory; and descending into a vale of almost primeval wildness, we continue our way up the ascent of “Artist’s Hill,” from whose summit on every side, as far as the eye can reach, the landscape softens into the hazy horizon. Returning, we pass through a ruined waste, where, three months before, the fierce tornado swooped down in its fiendish fury. On every side we see its awful evidences. Huge oaks, like brittle pipe-stems, snapped from their moorings; sturdy hickories, mere play-things in the gale, twisted into shreds.

WRECKS OF THE TORNADO.

Every morning saw me on some new drive, either with a wagon full of merry company, or as alone with Mr. Snug we held our quiet tête-à-tête on wheels, living over the olden times. In the afternoon I strolled by myself through the old and eloquent scenes. A volume could not hold the memories they revived – no, not even those of yonder barn alone. Even as I sit making my pencil-sketch, its reminiscences seem to float across the vision. Distinctly it recalls the events of one evening years ago. It was at about the sunset hour one Friday. I was quietly sitting on a lounge in the parlor talking to Cuthbert Harding, who was standing in front of me. Presently the door opens, and the tall figure of Dick Shin enters. Dick and I were antipodes in every sense of the word. Physically we were as a match and a billiard ball, he being the lucifer. He was also my bête noire, and he never missed an opportunity to vent his spite. Accordingly he stalked toward us, and with a violent push sent Cuthbert pell-mell on to me. In falling, he stepped heavily on my foot, and hurt me severely, which accounted for my excited expression as I threw him from me.

Of course Mr. Snug had to come in just at this time, and seeing us in what looked to him very like a fight, he took us firmly by the ears and stood us side by side, while I ventured to explain.

“Not a word!” exclaimed he, in a tone there was no mistaking. “You two boys may cool off on a trip to Moody Barn, after which you will report to me in the Tower. Now go.”

Whatever may have been the state of my mind a few moments before, I was now mad in earnest, and with every bit of my latent obstinacy aroused, I sauntered out on to the porch.

“Cool off, old boy,” whispered a grating voice at my side, as I turned and met the gaze of Dick Shin, motioning with his thumb in the direction of Moody Barn – “cool off; you need it;” and his ample mouth stretched into a sneering grin.

I had already formed an intention, but now it was a resolve.

“Cuthbert,” said I to my quiet and less choleric companion, when some distance down the road, “I am not going on that trip.”

“Not going!” replied he, with surprise; “why, you’ll have to go.”

“But I won’t go, and that settles it. It’s confounded unjust that we’re sent, anyhow, and I don’t propose to stand it.”

“I think so too,” answered Cuthbert, with hesitating emphasis; “but what’ll we do? We’ll have to report to Mr. Snug, you know; that’s the worst of it.”

“Well, I’ll be spokesman, and I’ll lie before I’ll go on that trip.”

I was boiling over with righteous wrath, but Cuthbert never was known to boil; he only simmered a little, but readily seconded my plan. We stopped at Kirby Corners, and there, secluded from view in the bushes, we spent the interval. Cuthbert had a watch, and by the light of the rising moon we were enabled to fix the full period for the trip. One hour and a half we allowed – an abundant limit. During this time I had completely “cooled off,” and had schooled myself to that point where I could tell a lie with a smooth face and a clear conscience. Accordingly, when the time came, we appeared at the door of the Tower. Mr. Snug was sitting in his accustomed place, and we entered and stood before him.

PASSING THOUGHTS.

“Well, sir,” said he, with a polite bow of the head, dropping his paper and looking up at us.

“Mr. Snug, we have come to report,” said I, fearlessly. “We have been to Moody Barn.”

Instantly Mr. Snug straightened himself up in his chair, pushed back the gray locks from his high forehead, and, with an expression that I never shall forget, glared at me from under the frowning eyebrows.

“You lie, sir!” he exclaimed, in thundering tones that fairly made my hair stand on end, while Cuthbert trembled from head to foot; then followed a brief moment of consternation that seemed an age. “Now go!” continued he, as with an emphatic nod of the head he motioned toward the door. Sheepish and crest-fallen, we slunk away from the room. It is needless to say that we went this time. Through the darkness, by the aid of a lantern, we picked our way, as with theories numerous and ingenious we strove to account for that vociferous reception.

Late that night we held an experience meeting with Mr. and Mrs. Snug in the Tower, and if I remember right there were a few tears that fell, and many apologies and good resolves, and as the true state of the case dawned on Mr. Snug there was an evident twinge of regret on his kind face.

On the following morning (Saturday) there was a jolly party of youths leaving the Snuggery for a day’s boating at the lake. Dick Shin was among them; and just as he was passing out the gate, a youngster approaches him and taps him on the shoulder. “You are hereby arrested, sir, on the orders of Mr. Snug.”

With an anxious and innocent expression Dick follows his juvenile constable into the Tower, and his companions stroll along after to ascertain the cause of the detention. We pass over the brief but amusing trial, in which the prisoner, with the innocence of a little lamb, pleaded his cause.

“You stumbled, did you?” said Mr. Snug. “Well, you ought to know, sir, by this time that I don’t allow young men to stumble in that way in my house. These two boys have suffered through your admitted clumsiness.” Here Mr. Snug paused in a moment’s thought. “Dick Shin,” he continued, “I sent these innocent young gentlemen on two trips to Moody Barn – that makes four miles for Bigson and four miles for Harding, together making eight that they walked on your account. Now you may put down your fishing-pole, and ‘stumble’ along on the road to Judd’s Bridge, which will give you two extra miles in which to think over your sins. And to make sure” – here Mr. Snug arose and went to the closet – “you may take this hatchet along with you, and bring me back a good big chip from the end of the long bridge beam. I shall ride over that way to-morrow and see whether it fits. You understand?”