полная версия

полная версияPastoral Days; or, Memories of a New England Year

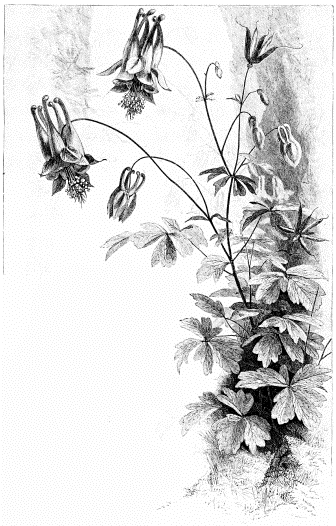

AMONG THE WILD FLOWERS.

THE COLUMBINE.

The grotesque Jack-in-the-pulpit, rising above that crumbling log, is named more to my mind. There he stands beneath his striped canopy, and preaches to me a sermon on the well-remembered rashness of my youth in trifling with that subterranean bulb from which he grows. But I ignored his warning in those early days. I only knew that a real nice boy across the way seemed very fond of those little Indian turnips, called them “sugar-roots,” and said that they were full of honey. And as he bit off his eager mouthful, and refused to let me taste, I sought one for myself, and, generous boy that he was, he showed me where to find the buried treasure. It was like a small turnip, an innocent-looking affair (and so was the nice boy’s modelled piece of apple, by-the-way). But oh! the sudden revelation of the red-hot reservoir of chain-lightning that crammed that innocent bulb! Even as I think of it, how I long once more to interview that real nice boy who opened up the mysteries of the “sugar-root” to my tempted curiosity. Let boys beware of this wild, red-hot coal; and should they be impelled by a desire to test the unknown flavor, let them solace themselves with a less dangerous mixture of four papers of cambric needles and a spoonful of pounded glass. This will give a faint suggestion of the racy pungency of the Indian turnip. Were some kind friend at the present day to seek to kill me off with poisoned food, I should forthwith have him arrested on a charge of attempted murder, and incarcerated in the county jail. But what would be wilful homicide in the man is only a guileless proof of friendship in the boy, and his affections and their symptoms present a living paradox; and those boisterous days, with all their fond caresses in the way of fights and bruises and black eyes, and even Indian turnips, we all agree were full of fun the like of which we never shall see again.

MEADOW BROOK.

How well we remember those tramps along the meadow brook: the dark, still holes beneath the overhanging rocks, where, with golden slipping loop and pole and cautious creep, we wired those lazy, unsuspecting “suckers” on the gravelly bed below! Ah! what scientific angling with the rod and reel in later years has ever brought back the keen tingle of that primitive sport? The great green bull-frogs, too, in the lily-pond, disclosing their cavernous resources as they jumped and splashed and sprawled after the tantalizing bit of red flannel on that dangling hook! We recall that rickety bridge among the willows, and the mossy nest of mud so firmly fixed upon the beam beneath. How could we be so deaf to the pleading of those little phoebe-birds that fluttered so beseechingly about us? Then there was that deep hole in the sand-bank near the brook, where the burrowing kingfisher hid away his nest, where we watched in the twilight to see him enter, and, with big round stone in readiness, “plugged” him in his den! What fun it was to dig him out, and ventilate his musty nest of fish-bones! The starling in the thicket of the swamp circled through the air with angry “Quit! quit!” as we picked our way through the bristling bogs so close upon her nest. We’ll not forget that false step that sent us sprawling in the green slimy mud, at the first electrifying glimpse of those brown spotted eggs. The high-holer, too, whose golden gleam of wing upon the bare dead tree betrayed his nesting-place in the hollow limb – was ever such a stimulus offered to the eagerness of youth? Who would give a second thought to his tender shins at the prospect of such a prize as a nest of high-hole’s eggs? How round and white they were! how the pale golden yolk floated beneath the pearly shell! Those were jolly days for us; but the poor birds had to suffer, and few, indeed, were the nests that escaped our prying search. There was the cat-bird in the evergreens, with lovely eggs of peacock blue; the pure white treasures of the swallows in the mud nests under the barn-yard eaves; the sky-blue beauties of the robin; the brown speckled eggs in the sheltered nest of song-sparrows on the grassy slope; the dear little eggs of chippies in their horse-hair bed, and in their midst the insinuated specimen of the cheeky cow-blackbird: there were eggs of every shape and hue, and we knew too well where to put our hand on them.

THE PHŒBE’S NEST.

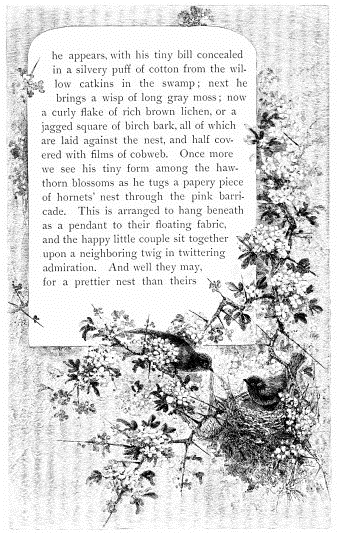

In a flowering hawthorn outside our window we watched a loving pair building their pensile nest among the thorns and blossoms. How incessant was their solicitude for that fragile framework until its strength was fully assured against the tossing breeze! Tenderly and eagerly they helped each other in the disposition of those ravellings of string and strips of bark! he stopping every now and then to whisper sweetly to his mate, as she, with drooping, trembling wings, put up her little open bill to kiss. Yes, we often saw this little tender episode, as we watched them through the shutters of the half-closed blinds! Now he flies away; and the little spouse, thus left alone, jumps into the nest, and we see its mossy meshes swell as she fits the deep hollow to her feathery breast. Presently her consort returns, trailing along a gossamer of cobweb, which he throws around the supporting thorn, and leaves for her to spread and tuck among the crevices. Again

BUILDING THE NEST.

never hung upon a thorn. Not perfect yet, it seems, however, for that little feminine eye has seen the need of one more touch. Away she flies, and in a minute more a downy feather, tipped with iridescent green, is adjusted in the cobwebs.

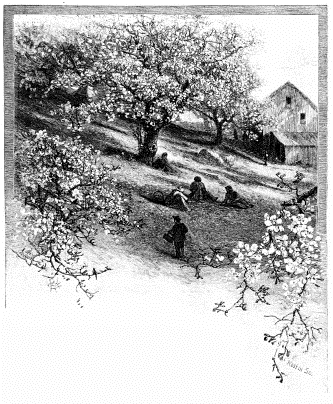

IN THE APPLE ORCHARD.

This dainty little work of art is only one of the thousands that everywhere are building in the blooming trees and thickets. These are the supreme moments of the spring, consecrated to the loves of bird and blossom. Every little winged form that scarcely bends the twig has its all-consuming passion, and every tree its wedding of the flower. Out in the orchard the apple-trees are laden in veritable domes of pink-white bloom, as if by the rare spectacle of a rosy fall of snow, and from among the dewy petals the army of bees give forth their low, continuous drone – that sympathetic chord in the universal harmony of spring. How they revel in that rich harvest! Who knows what sweet messages are borne from flower to flower upon those filmy wings?

On the green slope beneath, the scattered dandelions gleam like drops of molten gold upon the velvety sward, and a lounging family group, intent upon that savory noonday relish, gather the basketfuls of the dainty plants for that appetizing “mess of greens.” Often, while thus engaged, have I stopped to watch the antics of the festive bumblebee, tumbling around in the tufted blossom – always an amusing sight. See how he rolls and wallows in the golden fringe, even standing on his head and kicking in his glee! Presently, with his long black nose thrust deep into the yellow puff, he stops to enjoy a quiet snooze in the luxurious bed – an endless sleep, for I generally took this chance to put him out of his misery, preferring, perhaps, to watch the robin hopping across the lawn. Now he stops, and seems to listen; runs a yard or so, and listens again, and without a sign of warning dips his head, and pulls upon an unlucky angle-worm that much prefers to go the other way. It is a well-known fact that angle-worms approach the surface of their burrows at the sound of rain-drops on the earth above. I sometimes wonder if the robin in its quick running stroke of foot intends to simulate that sound, and thus decoy its prey.

I remember the wild tumult of a troop of boys upon the hill-side, tracking the swarming bees as they whirled along in a living tangle against the sky, now loosening in their dizzy meshes, now contracting in a murmuring hum around their queen, and finally settling on a branch in a pendent bunch about her. So tame and docile, too! seeming utterly to forget their fiery javelins as they hung in that brown filmy mass upon the bending bough! “A swarm of bees in May iz wuth a load o’ hay.” So said our neighbor, as with fresh clean hive he secured that prized equivalent. Here they are soon at home again, and we see their steady winged stream pouring out through the little door of their treasure-house, and the continual arrival of the little dusty plunderers, laden with their smuggled store of honey, and their saddle-bags replete with stolen gold. Down near the brook they find a land of plenty, literally flowing with honey, as the luxuriant drooping clusters of the locust-trees yield their brimful nectaries to the impetuous, murmuring swarm. But there is no lack now of flowery sweets for this buzzing colony. On every hand the meadow-sweets and milkweeds, the brambles, and the fragrant creeping-clover show their alluring colors in the universal burst of bloom, and not one escapes its tender pillaging.

Up in the woods the gray has turned to tender green. The flowering dog-wood has spread its layers of creamy blossoms, giving the signal for the planting of the corn, and in the furrowed field we see that dislocated “man of straw,” with old plug hat jammed down upon his face, with wooden backbone sticking through his neck-band, and dirty thatch for a shirt bosom – a mocking outrage on any crow’s sagacity. Those glittering strips of tin, too! Could you but interpret the low croaking of the leader of that sable gang in yonder tree, you might hear of the appalling effect of these precautions. I heard him once as I sat quietly beneath a forest tree, and in the light of later events I readily recalled his remarks upon the occasion: “Say, fellers! look at that old fool down there hanging out those tins to show us where his corn is planted. Haw! haw! I swaw! cawn! cawn! we’ll go down thaw and take a chaw!” And they did; and they perched upon that old plug hat, and looked around for something to get scared about. A single look at a crow shows that he has a long head, and it is not all mouth either.

Every day now makes a transformation in the landscape. The golden stars upon the lawn are nearly all burnt out: we see their downy ashes in the grass. Their virgin flame is quenched, and naught remains but those ethereal globes of smoke that rise up and float away with every breeze. Where is there in all nature’s marvels a more exquisite creation than this evanescent phœnix of the dandelion? Beautiful in life, it is even more beautiful in death. And now the high-grown grass is cloudy with its puffs, whose little fairy parachutes are sailing everywhere, over mountain-top and field. Here the corn has appeared in little waving plumes, and the horse and cultivator are seen breaking up the soil between the rows. Great snowy piles of cloud throw their gliding shadows across the patchwork of ploughed fields and meadows, fresh and

BLUE-FLAGS.

The chickadees are here, and scarlet tanagers gleam like living bits of fire among the tantalizing leaves. Pert little vireos hop inquisitively about you, and the bell note of the wood-thrush echoes from the hidden tree-top overhead. Perhaps, too, you may chance upon a downy brood of quail cuddling among the dry leaves; but, even though you should, you might pass them by unnoticed, except as a mildewed spot of fungus at the edge of a fallen log or tree-stump, perhaps. The loamy ground is shaded knee-deep with rank growth of wood plants. The mossy, speckled rock is set in a fringe of ferns. Palmate sprays of ginseng spread in mid-air a luxurious carpet of intermingled leaves, interspersed with yellow spikes of loosestrife and pale lilac blooms of crane’s-bill; and the poison-ivy, creeping like a snake around that marbled beech, has screened its hairy trunk beneath its three-cleft shiny leaves. The mountain-laurel, with its deep green foliage and showy clusters, peers above that rocky crag; and in the bog near by a thicket of wild azalea is crowned with a profusion of pink blossoms.

Out in the swamp meadow the tall clumps of boneset show their dull white crests, and the blue flowers of the flag, the mint, and pickerel weed deck the borders of the lily pond. The waddling geese let off their shrieking calliopes as they sail out into the stream, or browse with nodding twitch along the grassy bank. Swarms of yellow butterflies disgrace their kind as they huddle around the greenish mud-holes, and we hear on every side the “z-zip, z-zip,” amidst the din of a thousand crickets and singing locusts among the reeds and rushes. The meadows roll and swell in billowy waves, bearing like a white-speckled foam upon their crests a sea of daisies, with here and there a floating patch of crimson clover, or a golden haze of butter-cups. Rising suddenly from the tall grass near by, the gushing brimful bobolink crowds a half-hour’s song into a brief pell-mell rapture, beating time in mid-air with his trembling wings, and alighting on the tall fence-rail to regain his breath. A coy meadow-lark shows his yellow-breast and crescent above the windrow yonder, and we hear the ringing beats of whetted scythes, and see the mowers cut their circling swath.

Mowing! Why, how is this? This surely is not Spring. But even thus the Springtime leads us into Summer. No eye can mark the soft transition, and ere we are aware the sweet fragrance of the new-mown hay breathes its perfumed whisper, “Behold, the Spring has fled!”

SUMMER

“ALL out for Hometown.” There is an epidemic of eagerness, a general bustle for satchels and bundles, and the car is soon almost without a passenger; and, indeed, it would really seem as though the whole train had landed its entire human burden upon this platform; for Hometown is a popular place, and every Saturday evening brings just such an exodus as this: Husbands and fathers who fly from the hot and crowded city for a Sunday of quiet and content with their families, who year after year have found a refuge of peace and comfort in this charming New England town. Where is it? Talk with almost any one familiar with the picturesque boroughs of the Housatonic, and your curiosity will be gratified, for this village will be among the first to be described.

From the platform of the car we step into the midst of a motley assemblage, rustic peasantry and fashionable aristocracy intermingled. Anxious and eager faces meet you at every turn. For a few minutes the air fairly rings with kisses, as children welcome fathers, and fathers children. Strange vehicles crowd the depot – vehicles of all sizes and descriptions, from the veritable “one-hoss shay” to the dainty basket-phaeton of fashion. One by one the merry loads depart, while I, a pilgrim to my old home, stand almost unrecognized by the familiar faces around me. Leaning up against the porch near by, stands a character which, once seen, could never be forgotten. His face is turned from me, but the old straw hat I recognize as the hat of ten years ago, with brim pulled down to a slope in front, and pushed up vertically behind, and the identical hole in the side with the long hair sticking through. Yes, there he stands – Amos Shoopegg. I step up to him and lay my hand upon his shoulder. With creditable skill he unwinds the twist of his intricate legs, and with an inquiring gaze turns his good-natured face toward me.

“Is it possible that you don’t remember me, Shoop?”

With an expression of surprise he raises both his arms. “Wa’al, thar! I swaiou! I didn’t cal’late on runnin’ agin yeu. I was jes drivin’ hum from taown-meetin’, an’ thought as haow I’d take a turn in, jest out o’ cur’osity. Wa’al, naow, it’s pesky good to see yeu agin arter sech a long spell. I didn’t recognize ye at fust, but I swan when ye began a-talkin’, that was enuf fer me. Hello! fetched yer woman ’long tew, hey? Haow air yeu, ma’am? hope ye’er perty tol’ble. Don’t see but what yeu look’s nateral’s ever; but yer man here, I declar for’t, he got the best on me at fust;” and after having thus delivered himself, he swallowed up our hands in his ample fists.

“Yes, Shoop, I thought I’d just run up to the old home for a few days.”

“Wa’al, I swar! I’m tarnal glad to see ye, and that’s a fact. Anybody cum up arter ye? No? Well, then, s’posin’ ye jest highst into my team.” So saying, he unhitched a corrugated shackle-jointed steed, and backed around his indescribable impromptu covered wagon – a sort of a hybrid between a “one-hoss shay” and a truck.

“’Tain’t much of a kerridge fer city folks to ride in, that’s a fact,” he continued, “but I cal’late it’s a little better’n shinnin’ it.” After some little manœuvring in the way of climbing over the front seat, we were soon wedged in the narrow compass, and, with an old horse-blanket over our knees, we went rattling down the hill toward the village and home of my boyhood.

Years have passed since those days when, as a united family, we dwelt under that old roof; but those who once were children are now men and women, with divided interests and individual homes. The old New England mansion is now a homestead only in name, known so only in recollections of the past and the possibilities of the future.

“Wa’al, thar’s the old house,” presently exclaimed Amos, as we neared the brow of a declivity looking down into the valley below. “Don’t look quite so spruce as’t did in the old times, but Warner’s a good keerful tenant, ’tain’t no use talkin’. I cal’late yeu might dig a pleggy long spell afore yeu could git another feller like him in this ’ere patch.”

In the vale below, in its nest of old maples and elms, almost screened from view by the foliage, we look upon the familiar outlines of the old mansion, its diamond window in the gable peering through the branches at us. “Skedup!” cried Amos, as he urged his pet nag into a jog-trot down the hill, through the main street of the town. The long fence in front of the homestead is soon reached, a sharp turn into the drive, a “Whoa, January!” and we are extricated from the wagon.

“Wa’al, I’ll leave ye naow. I guess ye kin find yer way around,” said Shoop, as with one outlandish geometrical stride he lifted himself into the wagon. Cordially greeted by our hostess, with repeated urgings to “make ourselves at home,” we were shown to our room. The house, though clad in a new dress, still retained the same hospitable and cosy look as of old.

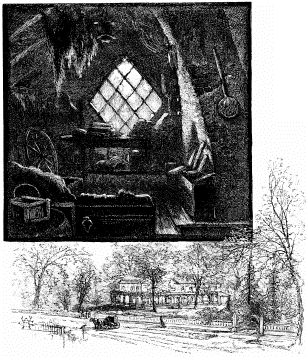

OLD HOMESTEAD AND GARRET.

Hometown, owing to some early local faction, is divided into two sections, forming two distinct towns. One, Newborough, a hill-top hamlet, with its picturesque long street, a hundred feet in width, and shaded with great weeping elms that almost meet overhead; and the other, Hometown proper, a picturesque little village in the valley, cuddling close around the foot of a precipitous bluff, known as Mount Pisgah. A mile’s distance separates the two centres. The old homestead is situated in the heart of Hometown, fronting on the main street. The house itself is a series of after-thoughts, wing after wing and gable after gable having clustered around the old nucleus, as the growth of new generations necessitated increased accommodation. Its outward aspect is rather modern, but the interior, with its broad open fireplaces, and accessaries in the shape of cranes and fire-dogs, is rich with all the features of typical New England; and the two gables of the main roof enclose the dearest old garret imaginable – at present an asylum for the quaint possessions of antique furniture and bric-à-brac, removed from their accustomed quarters on the advent of the new host. It is to this sanctuary that my footsteps first lead me, and, with a longing that will not be withstood, I find myself in front of the great white door. I lift the latch; a cool pungent odor of oak wood greets me as I ascend the steep stairs – an odor that awakens, like magic, a hundred fancies, and recalls a host of memories long forgotten. Every stair seems to creak a welcome, as when, on the rainy days of long ago, we sought the cosy refuge to hear the patter on the roof, or to nestle in the dark, obscure corners in our childish games. At the head of the stairs rises the ancient chimney, cleft in twain at the foot, with the quaint little cuddy between. Above me stretch the great beams of oak, like iron in their hardness. Yonder is the queer old diamond window looking out upon the village church, its panes half obscured by the dusty maze of webs. To the left, in a shadowy corner, stands the antiquated wheel – a relic of past generations. Long gray cobwebs festoon the rafters overhead, and the low buzzing of a wasp betrays its mud nest in the gable above. A sense of sadness steals over me as I sit gazing into this still chamber. On every side are mementos of a happy past, and all, though mute, speaking to me in a language whose power stirs the depths of my soul. Wherever the eye may turn, it meets with a silent greeting from an old friend, and the whole shrouded in a weird gloom that lends to the most common object an air of melancholy mystery. And yet it is only a garret. There are some, no doubt, for whom this word finds its fitting synonyme in the dictionary, but there are others to whom it sings a poem of infinite sweetness.

Looking through the dingy window between the maple boughs, my eye extends over lawn and shrubberies, three acres in extent – a little park, overrun with paths in every direction, through ancient orchard and embowered dells, while far beyond are glimpses of the wooded knolls, the winding brook, and meadows dotted with waving willows, and farther still the ample undulating farm.

It is in such a place as this that I have sought recreation and change of scene. My wife and I have run away from the city for a month or so. A vacation we call it; but to an artist such a thing is rarely known in its ordinary sense, and often, indeed, it means an increase of labor rather than a respite. My first week, however, I had consecrated to luxurious idleness. Together we wandered through the old familiar rambles where as boy and girl in earlier days we had been so oft together. Day after day found us in some new retreat. There were dark cool nooks by sheltered

AMONG THE GRASSES.

mist all through the blossoming maze. We heard the music of the scythe, and, sitting in the deep cool grass beneath the maple shade, we watched the circling motion of the mowers in the field – saw the forkfuls of the hay tossed in the drying sun, and breathed the perfumed air that floated from the windrows. We sauntered by the meadow brook where willows gleamed along the bank, and overhanging alders threw their sombre shadows in the quiet pools: where the ground-nut, and the meadow-rue, and the creeping madder fringed the tangled brink, and every footstep started up some agile frog that plunged into the unseen water. We stood where rippling shallows gurgled under festooned canopies of fox-grape, and the leaning linden-trees shut out the sky o’erhead and intertwined their drooping branches above the gliding current. Here, too, the weather-beaten crossing-pole makes its tottering span across the stream, and deep down beneath the bank the rainbow-tinted sunfish floats on filmy fins above his yellow bed of gravel, and we catch a flashing gleam of a silvery dace or shiner turning in the water.