полная версия

полная версияDecadence and Other Essays on the Culture of Ideas

Can one learn to write? Regarded as a question of style, this amounts to asking if, with application, M. Zola could have become Chateaubriand, or if M. Quesnay de Beaurepaire, had he taken pains, could have become Rabelais: if the man who imitates precious marbles by spraying pine panels with a sharp shake of his brush, could, properly guided, have painted the Pauvre Pêcheur, or if the stone-cutter, who chisels the depressing fronts of Parisian houses in the Corinthian manner, might not, perhaps, after twenty lessons, execute the Porte d'Enfer or the tomb of Philippe Pot?

Can one learn to write? If, on the other hand, the question be one of the elements of a trade, of what painters are taught in the academies, all that can indeed be learned. One can learn to write correctly, in the neutral manner, just as engravers used to work in the "black manner." One can learn to write badly – that is to say, properly, and so as to merit a prize for literary excellence. One may learn to write very well, which is another way of writing very ill. How melancholy they are, those books which are well-written – and nothing more!

III

M. Albalat has, then, published a manual entitled The Art of Writing Taught in Twenty Lessons. Had this work appeared at an earlier date, it would certainly have found a place in the library of M. Dumouchel, professor of literature, and he would have recommended it to his friends Bouvard and Pécuchet: "Then," as Flaubert tells us, "they sought to determine the precise constitution of style, and, thanks to the authors recommended by Dumouchel, they learned the secret of all the genres." However, the two old boys would have found M. Albalat's remarks somewhat subtle. They would have been shocked to learn that Télémaque is badly written and that Mérimée would gain by condensation. They would have rejected M. Albalat and set to work on their biography of the Duc d'Angoulême without him.

Such resistance does not surprise me. It springs, perhaps, from an obscure feeling that the unconscious writer laughs at principles, at the art of epithets, and at the artifice of the three graduated impulses. Had M. Albalat known that intellectual effort, and especially literary effort, is, in very large measure, independent of consciousness, he would have been less imprudent and hesitated to divide a writer's qualities into two classes: natural qualities and qualities that can be acquired. As if a quality – that is to say a manner of being and of feeling – were something external to be added like a colour or an odour. One becomes what he is – without wishing to even, and despite every effort to oppose it. The most enduring patience cannot turn a blind imagination into a visual imagination, and the work of a writer who sees the landscape, whose aspect he transposes into terms of literary art, is better, however awkward, than after it has been retouched by someone whose vision is void, or profoundly different. "But the master alone can give the salient stroke." I can see Pécuchet's discouragement at this. The master's stroke in artistic literature – even the salient stroke – is necessarily the very one on which stress should not have been laid. Otherwise the stroke emphasizes the detail to which it is customary to give prominence, and not that which had struck the unskilled but sincere inner eye of the apprentice. M. Albalat makes an abstraction of this almost always unconscious vision, and defines style as "the art of grasping the value of words and their interrelations." Talent, in his opinion, consists "not in making a dull, lifeless use of words, but in discovering the nuances, the images, the sensations, which result from their combinations."

Here we are, then, in the realm of pure verbalism – in the ideal region of signs. It is a question of manipulating these signs and arranging them in patterns that will give the illusion of representing the world of sensations. Thus reversed, the problem is insoluble. It may well happen, since all things are possible, that such combinations of words will evoke life – even a determinate life – but more often they will remain inert. The forest becomes petrified. A critique of style should begin with a critique of the inner vision, by an essay on the formation of images. There are, to be sure, two chapters on images in Albalat's book, but they come quite at the end. Thus the mechanism of language is there demonstrated in inverse order, since the first step is the image, the last the abstraction. A proper analysis of the natural stylistic process would begin with the sensation and end with the pure idea – so pure that it corresponded not only to nothing real, but to nothing imaginative either.

If there were an art of writing, it would be nothing more or less than the art of feeling, the art of seeing, the art of hearing, the art of using all the senses, whether directly or through the imagination; and the new, serious method of a theory of style would be an attempt to show how these two separate worlds – the world of sensations and the world of words – penetrate each other. There is a great mystery in this, since they lie infinitely far apart – that is to say, they are parallel. Perhaps we should see here the operation of a sort of wireless telegraphy. We note that the needles on the two dials act in unison, and that is all. But this mutual dependence is, in reality, far from being as complete and as clear as in a mechanical device. When all is said, the accords between words and sensations are very few and very imperfect. We have no sure means of expressing our thoughts, unless perhaps it be silence. How many circumstances there are in life, when the eyes, the hands, the mute mouth, are more eloquent than any words.35

IV

M. Albalat's analysis is, then, bad, because unscientific. Yet from it he has derived a practical method of which it may be said that, while incapable of forming an original writer – he is well aware of this himself – it might possibly attenuate, not the mediocrity, but the incoherence, of speeches and publications to which custom obliges us to lend some attention. Besides, even were this manual still more useless than I believe it to be, certain of its chapters would nevertheless retain their expository and documentary interest. The detail is excellent, as, for example, the pages where it is shown that the idea is bound up in the form, and that to change the form is to modify the idea. "It means nothing to say of a piece of writing that the substance is good, but the form is bad." These are sound principles, though the idea may subsist as a residue of sensation, independently of the words and, above all, of a choice of words. But ideas stripped bare, in the state of wandering larvae, have no interest whatever. It may even be true that such ideas belong to everybody. Perhaps all ideas are common property. But how differently one of them, wandering through the world, awaiting its evocator, will be revealed according to the word that summons it from the Shades. What would Bossuet's ideas be worth, despoiled of their purple? They are the ideas of any ordinary student of theology, and, uttered by him, such a farrago of stupid nonsense would shock and shame those who had listened to it intoxicated in the Sermons and Oraisons. And the impression will be similar if, having lent a charmed ear to Michelet's lyric paradoxes, we come across them again in the miserable mouthings of some senator, or in the depressing commentaries of the partisan press. This is the reason why the Latin poets, including the greatest of them all, Virgil, cease to exist when translated, all looking exactly alike in the painful and pompous uniformity of a normal student's rhetoric. If Virgil had written in the style of M. Pessonneaux, or of M. Benoist, he would be Benoist, he would be Pessonneaux, and the monks would have scrapped his parchments to substitute for his verses some good lease of a sure and lasting interest.

Apropos of these evident truths, M. Albalat refutes Zola's opinion that "it is the form which changes and passes the most quickly," and that "immortality is gained by presenting living creatures." So far as this second sentence can be interpreted at all, it would seem to mean that what is called life, in art, is independent of form. But perhaps this is even less clear? Perhaps it will seem to have no sense whatever. Hippolytus, too, at the gates of Troezen, was "without form and without colour" only he was dead. All that can be conceded to this theory is that, if a beautiful and original work of art survives its century and, what is more, the language in which it was written, it is no longer admired except as a matter of imitation, in obedience to the traditional injunction of the educators. Were the Iliad to be discovered to-day, beneath the ruins of Herculaneum, it would give us merely archaeological sensations. It would interest us in precisely the same degree as the Chanson de Roland; but a comparison of the two poems would then reveal more clearly than at present their correspondence to extremely different moments of civilization, since one is written entirely in images (somewhat stiff, it is true) while the other contains so few that they have been counted.

There is, moreover, no necessary relation between the merit of a work and its duration. Yet, when a book has survived, the authors of "analyses and extracts conforming to the requirements of the academic programme" know very well how to prove its "inimitable" perfection, and to resuscitate (for the brief time of a lecture) the mummy which will return once more to its linen bands. The idea of glory must not be confused with that of beauty. The former is entirely dependent upon the revolutions of fashion and of taste. The second is absolute to the extent of human sensations. The one is a matter of manners and customs; the other is firmly rooted in the law.

The form passes, it is true, but it is hard to see just how it could survive the matter which is its substance. If the beauty of a style becomes effaced or falls to dust, it is because the language has modified the aggregate of its molecules – words – as well as these molecules themselves, and because this internal activity has not taken place without swellings and disturbances. If Angelico's frescos have "passed," it is not that time has rendered them less beautiful, but that the humidity has swollen the cement where the painting has become caked and coated. Languages swell and flake like cement; or rather, they are like plane-trees, which can live only by constantly changing their bark, and which, early each spring, shed on the moss at their feet the names of lovers graven in their very flesh.

But what matters the future? What matters the approval of men who will not be what we should make them, were we demiurges? What is this glory enjoyed by man the moment he quits the realm of consciousness? It is time we learned to live in the present moment, to make the best of the passing hour, bad though it may be, and to leave to children this concern for the future, which is an intellectual weakness – though the naïveté of a man of genius. It is highly illogical to desire the immortality of works, when affirming and desiring the mortality of the soul. Dante's Virgil lived beyond life, his glory grown eternal. Of this dazzling conception there is left us but a little vain illusion, which we shall do well to extinguish entirely.

This does not mean, however, that we should not write for men as if we were writing for angels, and thus realize, according to our calling and our nature, the utmost of beauty, even though passing and perishable.

V

M. Albalat shows excellent judgment in suppressing the very amusing distinctions made by the old manuals between the florid style and the simple style, the sublime and the moderate. He deems justly that there are but two sorts of style: the commonplace and the original. Were it permitted to count the degrees from the mediocre to the bad, as well as from the passable to the perfect, the scale of shades and of colours would be long. It is so far from the Légende de Saint-Julien l'Hospitalier to a parliamentary discourse, that we really wonder if it is the same language in both cases – if there are not two French languages, and below them an infinite number of dialects almost entirely independent of one another. Speaking of the political style, M. Marty-Laveaux36 thinks that the people, having remained faithful in its speech to the traditional diction, grasps this very imperfectly and in a general way only, as if it were a foreign language. He wrote this twenty-seven years ago, but the newspapers, more widely circulated at present, have scarcely modified popular habits. It is always safe to estimate in France that, out of every three persons, there is one who reads a bit of a paper now and then by chance, and another who never reads at all. At Paris the people have certain notions concerning style. They have a special predilection for violence and wit. This explains the popularity, rather literary than political, of a journalist like Rochefort, in whom the Parisians have for a long time found once more their ancient ideal of a witty and wordy cleaver of mountains.

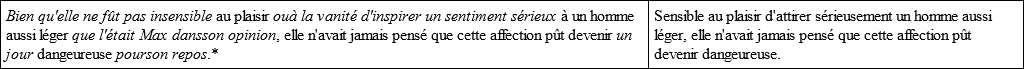

Rochefort is, moreover, an original writer – one of those who should be cited among the first to show that the substance is nothing without the form. To be convinced of this, one has only to read a little further than his own article in the paper which he edits. Yet we are perhaps fooled by him. We have been, it appears, for fully half a century, by Mérimée, from whom M. Albalat quotes a page as a specimen of the hackneyed style. Going farther, he indulges in his favourite pastime; he corrects Mérimée and juxtaposes the two texts for our inspection. Here is a sample:

* M. Albalat has italicized everything he deems "banal or useless."

It cannot, at least, be denied that the severe professor's style is economical, since it reduces the number of lines by nearly one-half. Subjected to this treatment, poor Mérimée, already far from fertile, would find himself the father of a few thin opuscules, symbolic thenceforth of his legendary dryness. Having become the Justin of all the Pompeius Troguses, Albalat places Lamartine himself upon the easel to tone down, for example, la finesse de sa peau rougissante comme à quinze ans sous les regards, to sa fine peau de jeune fille rougissante. What butchery! The words stricken out by M. Albalat are so far from being hackneyed that they would, on the contrary, correct and counteract the commonplaceness of the improved sentence. This surplusage conveys the exceedingly subtle observation of a man who has made a close study of women's faces – a man more tender than sensual, and touched by modesty rather than by carnal prestige. Good or bad, style cannot be corrected. Style is inviolable.

M. Albalat gives some very amusing lists of clichés, or hackneyed phrases; but this criticism, at times, lacks measure. I cannot accept as clichés "kindly warmth," "precocious perversity," "restrained emotion," "retreating forehead," "abundant hair," or even "bitter tears," for tears can be "bitter" and can be "sweet." It should be understood, also, that the expression which exists as a cliché in one style, can occur as a renewed image in another. "Restrained emotion" is no more ridiculous than "simulated emotion," while, as for "retreating forehead," this is a scientific and quite accurate expression, which one has only to be careful about employing in the proper place. It is the same with the others. If such locutions were banished, literature would become a kind of algebra and could no longer be understood without the aid of long analytical operations. If the objection to them is that they have been overworked, it would be necessary to forego all words in common use as well as those devoid of mystery. But that would be a delusion. The commonest words and most current expressions can surprise us. Finally, the true cliché, as I have previously explained, may be recognized by this, that, whereas the image which it conveys, already faded, is halfway on the road to abstraction, it is not yet sufficiently insignificant to pass unperceived and to take its place among the signs which owe whatever life they may possess to the will of the intelligence.37 Very often, in the cliché, one of the words has kept a concrete sense, and what makes us smile is less its triteness than the coupling of a living word with one from which the life has vanished. This can be seen clearly in such formulas as: "in the bosom of the Academy," "devouring activity," "open his heart," "sadness was painted on his face," "break the monotony," "embrace principles." However, there are clichés in which all the words seem alive —une rougeur colora ses joues; others in which all seem dead —il était au comble des ses vœux. But this last was formed at a time when the word comble was thoroughly alive and quite concrete. It is because it still contains the residue of a sensible image that its union with vœux displeases us. In the preceding example the word colorer has become abstract, since the concrete verb expressing this idea is colorier, and goes badly with rougeur and joues. I do not know just where a minute work on this part of the language, in which the fermentation is still unfinished, would lead us; but no doubt in the end it would be quite easy to demonstrate that, in the true notion of the cliché, incoherence has its place by the side of triteness. There would be matter in such a study for reasoned opinions that M. Albalat might render fruitful for the practice of style.

VI

It is to be regretted that he has dismissed the subject of periphrasis in a few lines. We expected an analysis of this curious tendency to replace by a description the word which is the sign of the thing in question. This malady, which is very ancient, since enigmas have been found on Babylonian cylinders (that of the wind very nearly in the terms employed by our children), is perhaps the very origin of all poetry. If the secret of being a bore consists of saying everything, the secret of pleasing lies in saying just enough to be, not understood even, but divined. Periphrasis, as handled by the didactic poets, is perhaps ridiculous only because of the lack of poetic power which it indicates; for there are many agreeable ways of not naming what it is desired to suggest. The true poet, master of his speech, employs only periphrases at once so new and so clear in their shadowy half-light, that any slightly sensual intelligence prefers them to the too absolute word. He wishes neither to describe, to pique the curiosity, nor to show off his learning; but, whatever he does, he employs periphrases, and it is by no means certain that all those he creates will remain fresh long. The periphrasis is a metaphor, and thus has the same life-span as a metaphor. It is far indeed from the vague and purely musical periphrases of Verlaine:

Parfois aussi le dard d'un insecte jaloux

Inquiétait le col des belles sous les branches,

to the mythological enigmas of a Lebrun, who calls the silkworm

"L'amant des feuilles de Thisbé."

Here M. Albalat appropriately quotes Buffon to the effect that nothing does more to degrade a writer than the pains he takes to "express common or ordinary things in an eccentric or pompous manner. We pity him for having spent so much time making new combinations of syllables only to say what is said by everybody." Delille won fame by his fondness for the didactic periphrasis, but I think he has been misjudged. It is not fear of the right word that makes him describe what he should have named, but rather his rigid system of poetics, and his mediocre talent. He lacks precision because he lacks power, and he is very bad only when he is not precise. But whether as a result of method or emasculation, we are indebted to him for some amusing enigmas:

Ces monstres qui de loin semblent un vaste écueil.

L'animal recouvert de son épaisse croûte,

Celui dont la coquille est arrondie en voûte.

L'équivoque habitant de la terre et des ondes.

Et cet oiseau parleur que sa triste beauté

Ne dédommage pas de sa stérilité.

It should not, however, be thought that the Homme des Champs, from which these charades are taken, is a poem entirely to be despised. The Abbé Delille had his merits and, once our ears, deprived of the pleasures of rhythm and of number, have become exhausted by the new versification, we may recover a certain charm in full and sonorous verses which are by no means tiresome, and in landscapes which, while somewhat severe, are broad and full of air.

… Soit qu'une fraîche aurore

Donne la vie aux fleurs qui s'empressent d'éclore,

Soit que l'astre du monde, en achevant son tour,

Jette languissamment les restes d'un beau jour.

VII

Yet M. Albalat asks how it is possible to be personal and original. His answer is not very clear. He counsels hard work and concludes that originality implies an incessant effort. This is a very regrettable illusion. Secondary qualities would, doubtless, be easier to acquire, but is concision, for example, an absolute quality? Are Rabelais and Victor Hugo, who were great accumulators of words, to be blamed because M. de Pontmartin was also in the habit of stringing together all the words that came into his head, and of heaping up as many as a dozen or fifteen epithets in a single sentence? The examples given by Albalat are very amusing; but if Gargantua had not played as many as two hundred and sixteen different and agreeable games under the eye of Ponocrates, we should feel very sorry, though "the great rules of the game are eternal."

Concision is sometimes the merit of dull imaginations. Harmony is a rarer and more decisive quality. There is no comment to be made on what Albalat says in this connection, unless it be that he believes a trifle too much in the necessary relations between the lightness or heaviness of a word, for example, and the idea which it expresses. This is an illusion which springs from our habits of thought, and an analysis of the sounds destroys it completely. It is not merely, says Villemain, imitation of the Greek or the Latin fremere that has given us the word frémir; it is also the relation of its sound to the emotion expressed. Horreur, terreur, doux, suave, rugir, soupirer, pesant, léger, come to us not only from Latin, but from an intimate sense which has recognized and adopted them as analogous to the impression produced by the object.38 If Villemain, whose opinion M. Albalat accepted, had been better versed in linguistics, he would doubtless have invoked the theory of roots, which at one time gave to his nonsense an appearance of scientific force. As it stands, the celebrated orator's brief paragraph would afford very agreeable matter for discussion. It is quite evident that if suave and suaire invoke impressions generally remote from each other, this is not because of the quality of their sound. In English, sweet and sweat are words which resemble each other. Doux is not more doux than toux and the other monosyllables of the same tone. Is rugir more violent than rougir or vagir? Léger is the contraction of a Latin word of five syllables, leviarium. If légère carries with it its own meaning, does mégère likewise? Pesant is neither more nor less heavy than pensant, the two forms being, moreover, doublets of a single Latin original, pensare. As for lourd, this is luridus, which meant many things: yellow, wild, savage, strange, peasant, heavy – such, doubtless, is its genealogy. Lourd is no more heavy than fauve is cruel. Think also of mauve and velours. If the English thin means the same as the French mince, how does it happen that the idea of its opposite, épais, is expressed by thick? Words are negative sounds which the mind charges with whatever sense it pleases. There are coincidences, chance agreements, between certain sounds and certain ideas. There are frémir, frayeur, froid, frileux, frisson. Yes; but there are also: frein, frère, frêle, frêne, fret, frime, and twenty other analogous sonorities, each of which is provided with a very different meaning.