полная версия

полная версияShinto

The Shinto shrine is by no means so costly an edifice as its Buddhist counterpart. The hokora,187 as the smaller shrines are called, are in many cases so small as to be easily transportable in a cart. Even the great shrines of Ise (pp. 228, 229) are of no great size and of purposely plain and simple construction. In 771 a "greater shrine" had only eighteen feet frontage. Some of the more important yashiro have smaller buildings attached to them, such as an emadō, or gallery of votive pictures; a haiden, or oratory, where the official representative of the Mikado performed his devotions, and a stage for the sacred pantomimic dance. A number of smaller shrines (sessha or massha) dedicated to other Gods are usually to be seen within the enclosure. No accommodation is provided for the joint worship of the congregation of believers, which is indeed exceptional. The individual worshipper stands outside in front of the shrine, calls the attention of the deity by ringing a gong provided for the purpose, bows his head, claps or folds his hands, puts up his petition, and retires. A large box stands conveniently for receiving such small contributions of copper cash as he may make.

In many shrines more than one deity is worshipped. These are called ahi-dono no kami, that is to say, deities of a joint shrine. They may, like Izanagi and Izanami, have some mythical connexion with each other or they may not. The Yengishiki enumerates 3,132 officially recognized shrines. Of these 737 were maintained at the cost of the Central Government. Some had permanent endowments of lands and peasants. Many minor shrines existed in all parts of the country. The shrines are classed as great and small, the respective numbers being 492 and 2,640. They differed in the quantity of offerings and in the circumstance that in the former case the offerings were placed on an altar and in the latter on the ground. Thirty-six shrines were situated in the palace itself. The most important deities worshipped here were eight in number, comprising five obscurely differentiated Musubi, the Goddess of Food, Oho-miya-no me, and Koto-shiro-nushi. There were also several Well-Gods, a Sono no Kami, a Kara no Kami (Korean God), a Thunder-God, a pair of sake deities, and others of whom little is known.

In enumerating the officially recognized shrines throughout the rest of the country the Yengishiki unfortunately, in the great majority of cases, does not name the God, but only the locality where the shrine was situated, as when we speak of Downing Street, meaning the collective officialdom of the place. This is in accordance with the impersonal habit of the Japanese mind already referred to. Strange to say, in some even of the most popular shrines, the identity of the God is doubtful or unknown. Kompira is a conspicuous example. According to some he is a demon, the alligator of the Ganges. Others say that Buddha himself became "the boy Kompira" in order to overcome the heretics and enemies of religion who pressed upon him one day as he was preaching. The mediæval Shintoists identified him with Susa no wo. More recently it has been declared officially that he is really Kotohira, an obscure Shinto deity, whose name has a resemblance in sound to that of the Indian God. His popularity has been little affected by these changes.188

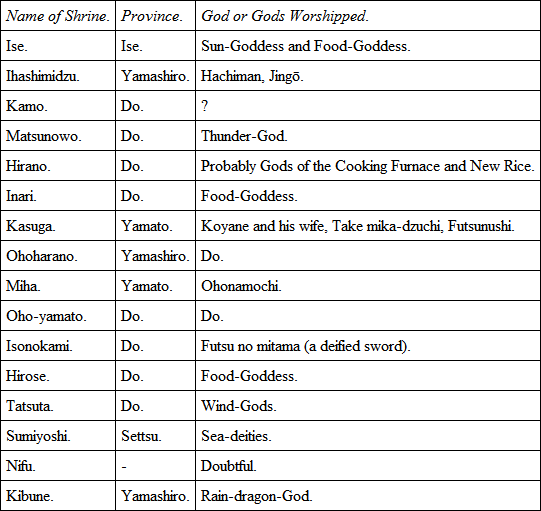

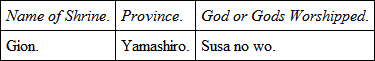

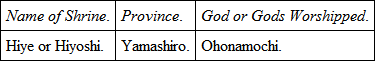

In 965 a selection of sixteen of the more important shrines was made to which special offerings were sent. These were as follows: -

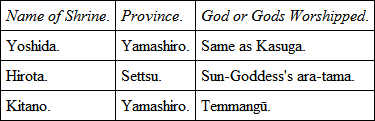

In 991 there were added the three following: -

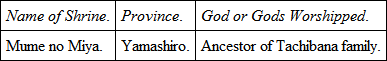

In 994 there was added

The next to be added was

The number was finally raised to twenty-two in 1039 by the addition of

Proximity to the capital no doubt influenced this selection. Idzumo, Kashima, Katori, Usa, Suha, and other important shrines are omitted. All the principal deities, however, are included in this list.

At the present day there are 193,476 Shinto shrines in Japan. Of these the great majority are very small and have no priests or revenues. Capt. Brinkley, in his 'Japan and China,' gives the following list of the ten most popular shrines in Japan at the present day: "Ise, Idzumo, Hachiman (Kyōto), Temmangū (Hakata), Inari (Kyōto), Kasuga (Nara), Atago (Kyōto), Kompira (Sanuki), Suitengū (Tōkyō), and Suwa (Shinano)."

Very many houses have their kamidana or domestic shrine, where the ujigami, the ancestor, and the trade-God, with any others whom there is some special reason for honouring, are worshipped.

Tori-wi. – The approach to a Shinto shrine is marked by one or more gateways or arches of the special form shown in the illustration (p. 233) and known as tori-wi. This word means literally "bird-perch," in the sense of a henroost. By analogy it was applied to anything of the same shape, as a clothes-horse, or the lintel of a door or gateway. As an honorary gateway, the tori-wi is a continental institution identical in purpose and resembling in form the turan of India, the pailoo of China, and the hong-sal-mun of Korea. When introduced into Japan at some unknown date (the Kojiki and Nihongi do not mention them) the Japanese called them tori-wi, which then meant simply gateway, but subsequently acquired its present more specific application. It sometimes serves the purpose of marking the direction of a distant object of worship.189

Hyaku-do ishi. – Near the front of the shrine may sometimes be seen a hyaku-do ishi, or hundred-time-stone, from which the worshipper may go back and forward to the door of the shrine a hundred times, repeating a prayer each time.

A sori-bashi or taiko-bashi, representing the mythical floating bridge of Heaven (the rainbow), is also to be seen at the approach to some shrines.

Prayer. – Private individual prayer is seldom mentioned in the old Shinto records, but of the official liturgies or norito we have abundant examples in the Yengishiki and later works. The authors are mostly unknown, but they were no doubt members of the Nakatomi House. Their literary quality is good. Motoöri observes that the elegance of their language is an offering acceptable to the Gods. The Sun-Goddess is represented in the Nihongi as expressing her satisfaction with the beauty of the norito recited in her honour.

The norito are addressed sometimes to individual deities, sometimes to categories of deities, as "the celebrated Gods" or "the Gods of Nankaido," and sometimes to all the Gods without exception. They contain petitions for rain in time of drought, good harvests, preservation from earthquake and conflagration, children, health and long life to the sovereign and enduring peace and prosperity to his rule, the safety of his ambassadors to foreign countries, the suppression of rebellion, the repulse of invasion, success to the Imperial arms, and general prosperity to the Empire. Sometimes the Mikado deprecates the wrath of deities whose services had been vitiated by ritual impurity, or whose shrines had suffered from neglect or injury.

The phrase "fulfilling of praises," which occurs frequently in the norito, must not be taken literally. It is really equivalent to "show all due honour to," and usually applies to the offerings which were made in token of respect. There is very little of praise in the ordinary meaning of the word. The language of the norito presents a striking contrast to the profusion of laudatory epithets and images of the Vedas, or the sublime eulogies of the Psalms of David. The only element of this kind is a few adjectival prefixes to the names of the Gods, such as oho, great; take, brave; taka, high; haya, swift; toyo, rich; iku, live; yori, good, and perhaps one or two more.

The do ut des principle of offerings is plainly avowed in some of the norito.

Besides petitions we find also announcements to the Gods, as of the appointment of a priestess, the bestowal on the deity of a degree of rank, and the beginning of a new reign. The Mongol invasion was notified to Ise in 1277 with the happiest results.

The Yengishiki contains no norito addressed to deceased Mikados, but several examples of this class, due no doubt to Chinese influence, have come down to us from the ninth century. In 850 Jimmu was prayed to for the Mikado, who was dangerously ill, and who died soon after. In the same year, "evil influences" (the Mikado's illness?) were attributed to his wrath, and envoys despatched to his tomb, in order to ascertain whether he might not have been offended by some pollution to it. The Empress Jingō was prayed to in 866 under similar circumstances. Other norito announce to the preceding Mikado the accession of a new sovereign or the appointment of a Prince Imperial.

The norito contain few petitions for which we might not easily find parallels in modern Europe, but a comparison with Christian, Jewish, or even Mohammedan and Buddhist formulæ reveals enormous lacunæ in the ancient Japanese conception of the scope of prayer. Moral and spiritual blessings are not even dreamt of. Such prayers as "that we may live a godly, righteous, and sober life," "to grant us true repentance and His Holy Spirit," are foreign to its character. "Lead us not into temptation" and "Thy will be done" are conspicuously absent. No Shinto God is petitioned to "endue the Sovereign with heavenly gifts," nor that "after this life he may attain everlasting joy and felicity." Indeed, there is no reference anywhere to a future life-a significant fact, in view of the circumstance that human sacrifices at the tombs of great men were at one time common. The commonly received opinion that the latter indicate a belief in a future state is, perhaps, after all, erroneous. Nor does any one beseech a Shinto deity to send down on the priesthood the healthful spirit of his grace.

Numerous specimens of norito will be found in Chap. XII.

In connexion with the attempted revival early in the last century of the pure Shinto of ancient times, Hirata composed a book of prayer entitled Tamadasuki, not for official or temple use, but as an aid to private devotion. It was not printed until some years after his death, and I doubt whether it was ever much used even by Shinto devotees. Notwithstanding the author's professed abhorrence of Buddhism and his condemnation of Chinese religious notions, the Tamadasuki owes much to these sources. He instructs his followers to "get up early, wash the face and hands, rinse the mouth, and cleanse the body. Then turn towards Yamato, clap hands twice, and bow down the head" before offering their petitions.

Prayers to the Shinto Gods, even at the present day, are mostly for material blessings. Anything more which they contain may be confidently set down to Buddhist influence. There are prayers on reclaiming a new piece of ground, building a house, sowing a rice-field, prayers for prosperity in trade and domestic happiness, prayers promising to give up sake, gambling, or profligacy (Buddhist), thanks for escape from shipwreck or other danger, &c. Sometimes the prayer is written out on paper and deposited in the shrine, perhaps accompanied by the petitioner's hair or a picture having some reference to the subject of his prayer. When it is answered, small paper nobori (flags) are set up at the shrine or its approaches. A common prayer at the present day is for "Peace to the country, safety to the family, and plentiful crops."

Oaths and Curses. – The Nihongi mentions several cases of Heaven or the Gods being appealed to for the sanction of an oath. Thus in 562 an accused person declares: "This is false and not true. If this is true, let calamity from Heaven befall me." In 581 tribes of Yemishi promised submission to the Mikado, saying: "If we break this oath, may all the Gods of Heaven and Earth and also the spirits of the Emperors destroy our race." In 644 the Mikado made an oath appealing to the Gods of Heaven and Earth, and saying: "On those who break this oath Heaven will send a curse and Earth a plague, demons will slay them, and men will smite them." The author of the Nihongi, however, is grievously open to the suspicion of adorning his narrative liberally with rhetorical ornaments of Chinese origin. The following is an example of a nonreligious oath said to have been made by a Korean king in 249: "If I spread grass for us to sit on, it might be burnt with fire; if I took wood for a seat, it might be washed away by water. Therefore, sitting on a rock, I make this solemn declaration of alliance." A curse pronounced over a well in 456 has likewise no religious quality. It is simply "This water may be drunk by the people only: royal persons alone may not drink of it." The instructions of the Sea-God to Hohodemi, "When thou givest this fishhook back to thy brother, say, 'A hook of poverty, a hook of ruin, a hook of downfall,'" are a kind of curse. On the whole, oaths and curses of a religious character are rare in Japanese literature. Profanity is almost unknown. A mild appeal to the "three holy things" (of Buddhism) or to the Sun, or a wish that divine punishment (bachi) may strike one's enemy, are almost the only things of the kind. And they are infrequent. Probably this is due to the want of a deep-seated sentiment of piety in the Japanese nation. Such expressions as "Thank God," "Good-bye," "Adieu," "God forbid," are also rare, whether in speech or in literature. The Mohammedans, with their continual use of the name of Allah, are the antipodes of the Japanese in this respect.

Rank of Deities. – A system of official ranks, borrowed from China, was introduced into Japan in the seventh century. There were at one time forty-eight different grades, each with its distinct costume, insignia, and privileges. The first notice of deities being granted such ranks occurs in 672, when we are told that three deities were "raised in quality" on account of useful military information supplied by their oracles. This practice became systematized in the period 749-757, and was very prevalent for several centuries longer. A rain of volcanic ashes which fell in many of the eastern provinces in 838 was attributed by the diviners to the jealousy of a Goddess, the true wife of a God, and mother by him of five children, at a step of official rank granted by the Mikado to a younger rival. Tantæ ne animis cælestibus iræ! In 851 Susa no wo and Oho-kuni-nushi received the lower third rank and in 859 were promoted to the upper third rank. The Mikado Daigo, on his accession in 898, raised the rank of 340 shrines. In 1076 and 1172 wholesale promotions of deities took place. After this time the custom fell into neglect, owing partly to the circumstance that many of the Gods had reached the highest class and could not be promoted any further. Several of the most important deities were not honoured in this way. The Sun-Goddess and the Food-Goddess were among this number. The same deity might have different ranks in different places. The lowness of the ranks with which the inferior deities were thought to be gratified is rather surprising. It throws a light on the mental attitude of the Japanese towards them. Beings who could be supposed to take pleasure in a D.S.O. or a brevet majority must have seemed to them not very far exalted above humanity.

Kagura. – This word is written with two Chinese characters which mean "God-pleasure." It is a pantomimic dance with music, usually representing some incident of the mythical narrative. Uzume's dance before the cave to which the Sun-Goddess had retired is supposed to be its prototype. Important shrines have a stage and a corps of trained girl-dancers (miko), for the purpose of these representations. Kagura was also performed in the Naishidokoro (the chamber in the Palace where the Regalia were kept), and under Chinese influences became a very solemn function, in which numerous officials were concerned. Many kinds of music, song, and dance are included in this term. It was the parent in the fourteenth century of the No, a sort of religious lyrical drama, and less directly of the modern popular drama.

Some authorities say that the music of the Kagura consisted at first of flutes made by opening holes between the joints of a bamboo, of wooden castanets, and of a stringed instrument made by placing six bows together.

Pilgrimages. – Paying visits is a recognized mode of showing respect to Gods as it is to men. The Mikado himself formerly paid frequent visits to the shrines of Kiōto and the vicinity, and in all periods of history embassies were continually despatched by him to the great shrines of the Empire. The private worshipper, besides visiting the shrine of his local deity, generally makes it his business, at least once in his lifetime, to pay his respects to more distant Gods, such as those of Ise, Miha, Ontake, Nantai (at Nikko), Kompira, Fujiyama, Miyajima, &c. Intending pilgrims associate themselves in clubs called Kō, whose members each contribute five sen a month to the pilgrimage fund. When the proper time of year comes round, a certain number of members are chosen by lot to represent the club at the shrine of their devotion, all expenses being defrayed out of the common fund. One of the number who has made the pilgrimage before acts as leader and cicerone. As a general rule the pilgrims wear no special garb, but those bound for Fuji, Ontake, or other high mountains may be distinguished by their white clothes and sloping broad hats. While making an ascent, they often ring a bell and chant the prayer, "May our six senses be pure and the weather fair on the honourable mountain."190 Many thousand pilgrims annually ascend Fuji, and over 11,000 paid their devotions at Ise on a recent New Year's day. Almost all Japanese cherish the hope of visiting this shrine at least once in their lives, and many a Tokio merchant thinks that his success in business depends largely on his doing so. Pilgrimages are an ancient institution in Japan. It is recorded that in the ninth month of 934, 10,000,000 pilgrims of all classes visited the shrines of Ise.

Boys and even girls often run away from their homes and beg their way to Ise. This is regarded as a pardonable escapade.

When an actual visit to a shrine is inconvenient or impossible, the worshipper may offer his devotions from a distance. This is called em-pai, or distant worship. Special shrines are provided in some places where the God will accept such substituted service. Processions may be joint formal visits of the worshippers to the God's shrine, but they oftener consist in attending him on an excursion from it to some place in the neighbourhood and back again. They much resemble in character the carnival processions of Southern Europe.

Circumambulation. – The Brahmanic and Buddhist ceremony of pradakchina, that is, going round a holy object with one's right side turned to it, is not found in Shinto. The principle, however, on which it rests-namely, that of following or imitating the course of the Sun-is recognized in the Jimmu legend. Jimmu says:191 "If I should proceed against the Sun to attack the enemy, I should act contrary to the way of Heaven… Bringing on our backs the might of the Sun-Goddess, let us follow her rays and trample them down." It is difficult to reconcile with this a passage in the Kojiki192 where it is counted unlucky for the Mikado to travel from East to West, because in so doing he must turn his back upon the Sun.

Horses presented to shrines were led round them eight times.

CHAPTER XI.

MORALS, LAW, AND PURITY

In the previous chapter we dealt with the positive side of religious conduct. We have now to examine its negative aspect, namely, those prohibitions which fall under the general description of morality and ceremonial purity.

Morals. – Before proceeding to examine the relation of morals to religion in Shinto, let us note some general considerations. Right conduct has three motives: first, selfish prudence; second, altruism, in the various forms of domestic affection, sympathy with others and respect for their rights, public spirit, patriotism and philanthropy; and third, the love of God. Conduct which is opposed to these three sanctions is called in the case of the first folly, of the second crime, and of the third sin; to which are opposed prudence, morality, and holiness. With the infant and the savage the first motive predominates. With advancing age in the individual, and civilization in the race, the second and third assume more and more importance. All but the lowest grades of animals have some idea of prudential restraint. Many are influenced by the domestic affections, while the higher, and especially the gregarious species, have some rudiments of the feeling of obligation towards the community, on which altruistic morality and eventually law are based. But in the lower animals, and even in many men, the religious sanction is wanting.

Right conduct may usually be easily referred to an origin in one or other of these three classes of motives. The duty of refraining from excess in eating and drinking belongs primarily to the first, the care of children and the avoidance of theft, murder, or adultery to the second, acts of worship and abstinence from impiety and blasphemy to the third. There is, however, a tendency for these motives to encroach on each other's provinces without relinquishing their own. Acts which belong at first to one category end by receiving the sanction of the other motives. Drunkenness, at first thought harmless, is soon recognized as folly, though harming nobody but the drunkard himself. It is eventually seen to be also a crime against the community, and last of all a sin in the eyes of God. Criminal Law is a systematic enforcement of the rights of others by adding prudential motives for respecting them. It also punishes blasphemy and heresy, no doubt for the protection of the interests of the community against the curse which such offences bring down. With ourselves religion condemns not only direct offences against the Deity as in the first three commandments, but selfish folly, and throws its ægis over the rights of our neighbour, by prohibiting theft, murder, adultery, lying, disrespect to parents, &c. Can it be doubted that these were already offences before the ten commandments were delivered from Mount Sinai?

There is no stronger proof of the rudimentary character of Shinto than the exceedingly casual and imperfect sanction which it extends to altruistic morality. It has scarcely anything in the nature of a code of ethics. Zeus had not yet wedded Themis. There is no direct moral teaching in its sacred books. A schedule of offences against the Gods, to absolve which the ceremony of Great Purification was performed twice a year,193 contains no one of the sins of the Decalogue.194 Incest, bestiality, wounding, witchcraft, and certain interferences with agricultural operations are the only offences against the moral law which it enumerates. The Kojiki speaks of a case of homicide being followed by a purification of the actor in it. But the homicide is represented as justifiable, and the offence was therefore not so much moral as ritual.195 Modern Japanese boldly claim this feature of their religion as a merit. Motoöri thought that moral codes were good for Chinese, whose inferior natures required such artificial means of restraint. His pupil Hirata denounced systems of morality as a disgrace to the country which produced them. In 'Japan,' a recent work published in English by Japanese authors, we are told that "Shinto provides no moral code, and relies solely on the promptings of conscience for ethical guidance. If man derives the first principles of his duties from intuition, a schedule of rules and regulations for the direction of everyday conduct becomes not only superfluous but illogical."