полная версия

полная версияSurnames as a Science

Another difference to be noted is that whereas all our settlements seem to have been made in heathen times, those of Germany extend into Christian times, as shown by such names as Johanningen, Jagobingen, and Steveningen, containing the scriptural names John, Jacob and Stephen. There is another and a curious name, Satanasinga, which, the place to which it is applied being a waste, seems to describe the people who lived in it, or around it, perhaps in reference to their forlorn condition, as "the children of Satan." The adoption of scriptural names seems to have taken place at a later period in England than either in Germany or in France. And we have not, as I believe, a single instance in our surnames of a scriptural name in an Anglo-Saxon patronymic form, as the Germans, judging from the above, might – possibly may – have.

Another point of difference between the Anglo-Saxon and the German settlements would seem to be this, that while the German list contains a considerable proportion of compound names, such as Willimundingas and Managoldingas, the Anglo-Saxon list consists almost exclusively of names formed of a single word, and the exceptions may almost be counted upon the fingers. With this I was at first considerably puzzled, but on looking more carefully into the lists, it seemed to me apparent that many of the names assumed by Mr. Kemble from names of places were in reality compound names in a disguised and contracted form. And as Tidmington, whence he derives Tidmingas, was properly Tidhelmingtun, so I conceive that Osmingas derived from Osmington, ought properly to be Oshelmingas, and Wylmingas, found in Wilmington, to be Wilhelmingas. So also I take it that Wearblingas, found in Warblington, ought to be Warboldingas, that Weomeringas, deduced from Wymering, ought to be Wigmeringas, and that Horblingas, found in Horbling, ought to be Horbaldingas. There are several other names, such as Scymplingas, Wramplingas, Wearmingas, Galmingas, &c., that seem as they stand, to be scarcely possible for names of men, and which may also contain compounds in a corrupted or contracted form. In addition to this, I note the following, found in ancient charters, which Mr. Kemble seems to have overlooked, Ægelbyrhtingas, found in Ægelbyrtingahyrst, No. 1041, Ceolredingas, found in Colredinga gemerc, 1149, and Godhelmingas found in Godelmingum, 314. If all these were taken into account, the difference, though it would still exist, might not be so great as to be unaccountable, considering that our settlements were made to a considerable extent at an earlier date, and by tribes more or less differing from those of Germany. It raises, moreover the question, dealt with in a very thorough manner by Stark, as to the extent to which these short and simple names may be contractions of compound names. I have referred to the subject in another place, and I will only observe at present that from the instances he cites the practice seems to have been rather specially common among the Frisians. Now it will be found on comparing the names of our ancient settlers with the Frisian names past and present cited by Outzen and Wassenberg, that there is a very strong family likeness between them, though we need not take it to amount to more than this, that the Frisian names may be taken as a type of the kind of names prevalent among the other neighbouring Low German tribes, until it can be more distinctly shown that there were settlements made by the Frisians themselves. And I have brought these names into the comparison simply as being the nearest representatives that I can find.

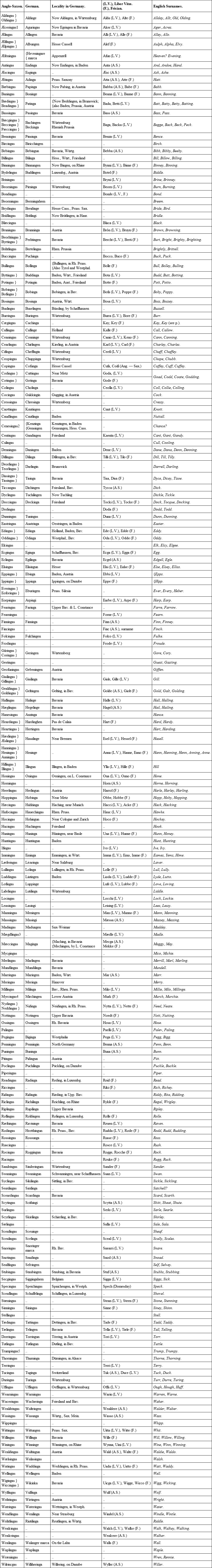

Notwithstanding the complete and valuable tables drawn up by Mr. Taylor for the purpose of comparing the Anglo-Saxon settlements with those of Germany, I have thought it useful to supplement them by another confined exclusively to the names drawn from ancient German records, and therefore, so far as they go, entirely trustworthy. And I take the opportunity to compare our existing surnames with these ancient names thus shown to be common to the great Teutonic family.

In the following table I have given then, first the Anglo-Saxon names from Kemble's lists, then the corresponding Old German from that of Foerstemann, with the district in which it is found, and, wherever identified, the existing name of the place, then names corresponding from the Liber Vitæ or elsewhere to show continued Anglo-Saxon use, with also Frisian names as already mentioned, and finally, the existing English surnames with which I compare them. It will be seen that these surnames in not a few cases retain an ancient vowel-ending in a, i, or o, as explained in a preceding chapter.

THE EARLY SAXON SETTLEMENTS COMPARED WITH THOSE OF GERMANY.

1. The reader must bear in mind that Ang. – Sax. æ is pronounced as a in "ant."

2. I take the word contained herein to be "ganz," an ancient stem in names.

3. Properly, I think, "Mædlingas," as it has nothing to do with Ang. – Sax. "mægd," maid.

4. The same, I take it, as the "Myrgingas" in the Traveller's Tale.

5. Properly, I take it, "Trumingas," Ang. – Sax. "trum" firm, strong.

I may observe with regard to the Anglo-Saxon names in the above lists that there is occasionally a little corruption in their forms. The English trouble with the letter h seems to have been present even at this early day. We have Allingas and Hallingas, Anningas and Hanningas, Eslingas and Haslingas, Illingas and Hillingas, in all of which cases the analogy of Old German names would show the h to be in all probability an intruder. And the same applies to the Hanesingas, the Honingas, and the Hoppingas. There is also an occasional intrusion of b or p, thus the Trumpingas, whence the name of Trumpington, should be properly, I take it, Trumingas, A.S. trum, firm, strong. Stark suggests a Celtic word, drumb, but the intrusion of p is so easy that I think any other explanation hardly necessary. The Sempingas, found in Sempingaham, now Sempringham, should also, I take it, be Semingas, which would be in accordance with Teutonic names, whereas semp is a scarcely possible form. Basingstoke, the original of which was Embasingastoc, owes its name to a similar mistake. It would be properly I think Emasingastoc, which would correspond with a Teutonic name-stem. A similar intrusion of t occurs in the case of Glæstingabyrig (now Glastonbury), which should I think be Glæssingabyrig; this again would correspond with an ancient name-stem, which in its present form it does not. So also I take it that Distingas, found in Distington in Cumberland, is only a phonetic corruption of Dissingas, if indeed, (which I very strongly doubt) Distington is from a tribe-name at all. Both of these intrusions are natural from a phonetic point of view, tending as they do to give a little more backbone to a word, and they frequently occur, as I shall have elsewhere occasion to note, in the range of English names.

My object in the present chapter has been more especially to show the intimate connection between our early Saxon names, and those of the general Teutonic system. But now I come to a possible point of difference. All the names of Germany would tend to come to England, but if Anglo-Saxon England made any names on her own account, they would not go back to Germany. For the tide of men flows ever west-ward, and there was no return current in those days. Now there do seem to be certain name-stems peculiar to Anglo-Saxon England, and one of these is peht or pect, which may be taken to represent Pict. The Teutonic peoples were in the habit of introducing into their nomenclature the names of neighbouring nations even when aliens or enemies. Thus the Hun and the Fin were so introduced, the latter more particularly by the Scandinavians who were their nearest neighbours. There is a tendency among men to invest an enemy upon their borders, of whom they may be in constant dread, with unusual personal characteristics of ferocity or of giant stature. Thus the word Hun, as Grimm observes, seems to have become a synonym of giant, and Ohfrid, a metrical writer of the ninth century, describes the giant Polyphemus as the "grosse hun." Something similar I have noted (in a succeeding chapter on the names of women, in voce Emma) as possibly subsisting between the Saxons and their Celtic neighbours. The Fins again, who as a peculiarly small people could not possibly be magnified into giants, were invested with magical and unearthly characteristics, and the word became almost, if not quite, synonymous with magician. This then seems to represent something of the general principle, upon which such names have found their way into the Teutonic system of nomenclature.

While then England received all the names formed from peoples throughout the Teutonic area, the Goth, the Vandal, the Bavarian, the Hun, and the Fin, in the names of men, there was one such stem which she had and which the rest of Germany had not, for she alone was neighbour to the Pict. Perhaps I should qualify this statement so far as the Old Saxons of the seaboard are concerned, for they were also neighbours, though as far as we know, the Pict did not figure in their names of men. From the stem pect the Anglo-Saxons had a number of names, as Pecthun or Pehtun, Pecthath, Pectgils, Pecthelm, Pectwald, Pectwulf, all formed in accordance with the regular Teutonic system, but none of them found elsewhere than in Anglo-Saxon England. Of these names we may have one, Pecthun, in our surname Picton, perhaps also the other form Pehtun in Peyton or Paton. The Anglo-Saxons no doubt aspirated the h in Pehtun, but we seem in such cases either to drop it altogether, or else to represent it by a hard c, according perhaps as it might have been more or less strongly aspirated. Indeed the Anglo-Saxons themselves would seem to have sometimes dropped it altogether, if the name Piott, in a will of Archbishop Wulfred, A.D. 825, is the same word (which another name Piahtred about the same period would rather seem to indicate). And this suggests that our name Peat may be one of its present representatives. We have again a name Picture, which might represent an Anglo-Saxon Pecther (heri, warrior) not yet turned up, but a probable name, the compound being a very common one.

I do not think it necessary to go into the case of any other name-stem which I do not find except among the Anglo-Saxons, inasmuch as, there being in their case no such reason for the restriction as in that to which I have been referring, it may only be that they have not as yet been disinterred.

CHAPTER V.

MEN'S NAMES IN PLACE-NAMES

We have seen in a preceding chapter that the earliest Saxon place-names in England are derived from a personal name, and that the idea contained is that of a modified form of common right. We shall find that a very large proportion of the later Anglo-Saxon place-names are also derived from the name of a man, but that the idea contained is now that of individual ownership or occupation. The extent to which English place-names are derived from ancient names of men is, in my judgment, very much greater than is generally supposed. And indeed, when we come to consider it, what can be so naturally associated with a ham as the name of the man who lived in that home, of a weorth as that of the man to whom that property belonged, of a Saxon tun or a Danish by or thorp as that of the man to whom the place owed its existence? If we turn to Kemble's list of Anglo-Saxon names of places as derived from ancient charters, in the days when the individual owner had succeeded to the community, we cannot fail to remark to how large an extent this obtains, and how many of these names are in the possessive case. Now, it must be observed that there are in Anglo-Saxon two forms of the possessive, and that when a man's name had the vowel ending in a, as noted at p. 24, it formed its possessive in an, while otherwise it formed its possessive in es. Thus we have Baddan byrig, "Badda's borough," Bennan beorh, "Benna's barrow" or grave, and in the other form we have Abbodes byrig, "Abbod's borough," Bluntes ham, "Blunt's home," and Sylces wyrth, "Silk's worth" or property. And as compound names did not take a vowel ending, such names invariably form their possessive in es, as in Haywardes ham, "Hayward's home," Cynewardes gemæro, "Cyneward's boundary," &c. I am not at all sure that ing also has not, in certain cases, the force of a possessive, and that Ælfredincgtun, for instance, may not mean simply "Alfred's town" and not Alfreding's town. But I do not think that this is at any rate the general rule, and it seems scarcely possible to draw the line. From the possessive in an I take to be most probably our present place-names Puttenham, Tottenham, and Sydenham, (respecting the last of which there has been a good deal of discussion of late in Notes and Queries), containing the Anglo-Saxon names Putta, Totta, and Sida. With regard to the last I have not fallen in with the name Sida itself. But I deduce such a name from Sydanham, C.D. 379, apparently a place in Wilts, also perhaps from Sidebirig, now Sidbury, in Devon; and there is, moreover, a corresponding O.G. Sido, the origin being probably A.S. sidu, manners, morals. Further traces of such a stem are found in Sidel deduced from Sidelesham, now Sidlesham, in Sussex, and also from the name Sydemann in a charter of Edgar, these names implying a pre-existing stem sid upon which they have been formed.

As well as with the ham or the byrig in which he resided, a man's name is often found among the Anglo-Saxons, connected with the boundary – whatever that might be – of his property, as in Abbudes mearc, Abbud's mark or boundary, and Baldrices gemæro, Baldrick's boundary. Sometimes that boundary might be a hedge, as in Leoferes haga and Danehardes hegeræw, "Leofer's hedge," and "Danehard's hedge-row." Sometimes it might be a stone, as in Sweordes stân, sometimes a ridge, as in Eppan hrycg, "Eppa's ridge," sometimes a ditch or dyke, as in Tilgares dic and Colomores sîc (North. Eng. syke, wet ditch). A tree was naturally a common boundary mark, as in Potteles treôw, Alebeardes âc (oak), Bulemæres thorn, Huttes æsc (ash), Tatmonnes apoldre (apple-tree). Sometimes, again, a man's name is found associated with the road or way that led to his abode, as in Wealdenes weg (way), Sigbrihtes anstige (stig, a footpath), Dunnes stigele (stile). Another word which seems to have something of the meaning of "stile" is hlip, found in Freobearnes hlyp and in Herewines hlipgat. In Anglo-Saxon, hlypa signified a stirrup, and a "hlipgat" must, I imagine, have been a gate furnished with some contrivance for mounting over it. Of a similar nature might be Alcherdes ford, and Brochardes ford, and also Geahes ofer, Byrhtes ora, and Æscmann's yre (ofer, contr. ore, shore or landing-place). Something more of the rights of water may be contained in Fealamares brôc (brook), Hykemeres strêm (stream), and Brihtwoldes wêre (weir); the two latter probably referring to water-power for a mill. The sense of property only seems to be that which is found in Cybles weorthig, Æscmere's weorth (land or property), Tilluces leah (lea), Rumboldes den (dene or valley), Bogeles pearruc (paddock), Ticnes feld (field). Also in Grottes grâf (grove), Sweors holt (grove), Pippenes pen (pen or fold), Willeardes hyrst (grove), Leofsiges geat (gate), Ealdermannes hæc (hatch), and Winagares stapol (stall, market, perhaps a place for the sale or interchange of produce). The site of a deserted dwelling served sometimes for a mark, as in Sceolles eald cotan (Sceolles old cot), and Dearmodes ald tun (Deormoda's old town, or inclosure, dwelling and appurtenances?).

But it is with a man's last resting-place that his name will be found in Anglo-Saxon times to be most especially associated. The principal words used to denote a grave are beorh (barrow), byrgels, and hlœw (low), in all of which the idea seems to be that of a mound raised over the spot. We have Weardes beorh, "Weard's barrow," also Lulles, Cartes, Hornes, Lidgeardes, and many others. We have Scottan byrgels, "Scotta's barrow," also Hôces, Wures, and Strenges. And we have Lortan hlæw, "Lorta's low," also Ceorles, Wintres, Hwittuces, and others. There is another word hô, which seems to be the same as the O.N. haugr, North. Eng, how, a grave-mound. It is found in Healdenes hô, Piccedes hô, Scotehô Tilmundes hô, Cægeshô, and Fingringahô. It would hardly seem, from the location of four of them, Worcester, Essex, Beds, Sussex, that they can be of Scandinavian origin. Can the two words, haugr and hlau (how, and hlow), be from the same origin, the one assuming, or the other dropping an l?

I take the names of persons thus to be deduced from Anglo-Saxon place-names, and which are in general correspondence with the earlier names in the preceding chapter, though containing some new forms and a greater number of compound names, to give as faithful a representation as we can have of the every-day names of Anglo-Saxons. And as I have before compared the names of those primitive settlers with our existing surnames, so now I propose to extend the comparison to the names of more settled Anglo-Saxon times.

1 Cf. also Diormod, moneyer on Anglo-Saxon coins, minted at Canterbury. There is, however, an Irish Diarmaid which might in certain cases intermix, and whence we must take McDermott.

2 I take Ealdermann to be, as elsewhere noted, a corruption of Ealdmann.

3 Mr. Kemble, in default of finding Hygelac as a man's name in Anglo-Saxon times, has taken the above place-name to be from the legendary hero of that name. The fact is, however, that Hygelac occurs no fewer than four times as an early man's-name in the Liber Vitæ, so that there does not seem to be any reason whatever for looking upon it as anything else than the every-day name of an Anglo-Saxon.

4 From a similar origin is probably Shooter's Hill, near London.

5 There is also an A.S. Sæbriht, from sæ, sea, whence Seabright might be derived.

6 Upon the whole I am inclined to think that Woden is here an Anglo-Saxon man's name, though the traces of it in such use are but slight. There is a Richard Wodan in the Lib. Vit. about the 15th century. And Wotan occurs once as a man's name in the Altdeutsches Namenbuch.

The above names are deduced entirely from the names of places found by Mr. Kemble in ancient charters. The list is not by any means an exhaustive one, as I have not included a number of names taken into account in Chap. IV., and as also the same personal name enters frequently into several place-names. With very few exceptions these names may be gathered to the roll of Teutonic name-stems, notwithstanding a little disguise in some of their forms, and a great, sometimes a rather confusing, diversity of spelling. I take names such as the above to be the representatives of the every-day names of men in Anglo-Saxon times, rather than the names which come before us in history and in historical documents. For it seems to me that a kind of fashion prevailed, and that while a set of names of a longer and more dignified character were in favour among the great, the mass of the people still, to a great extent, adhered to the shorter and more simple names which their fathers had borne before them. Thus, when we find an Æthelwold who was also called Mol, an Æthelmer who was also called Dodda, and a Queen Hrothwaru who was also called Bucge, I am disposed to take the simple names, which are such as the earlier settlers brought over with them, to have been the original names, and superseded by names more in accordance with the prevailing fashion. Valuable then as is the Liber Vitæ of Durham, as a continuous record of English names for many centuries, yet I am inclined to think that inasmuch as that the persons who come before us as benefactors to the shrine of St. Cuthbert may be taken to be as a general rule of the upper ranks of life, they do not afford so faithful a representation of the every-day names of Anglo-Saxons as do the little freeholders who lived and died in their country homes. And, moreover, these are, as it will be seen, more especially the kind of names which have been handed down from Anglo-Saxon times to the present day.

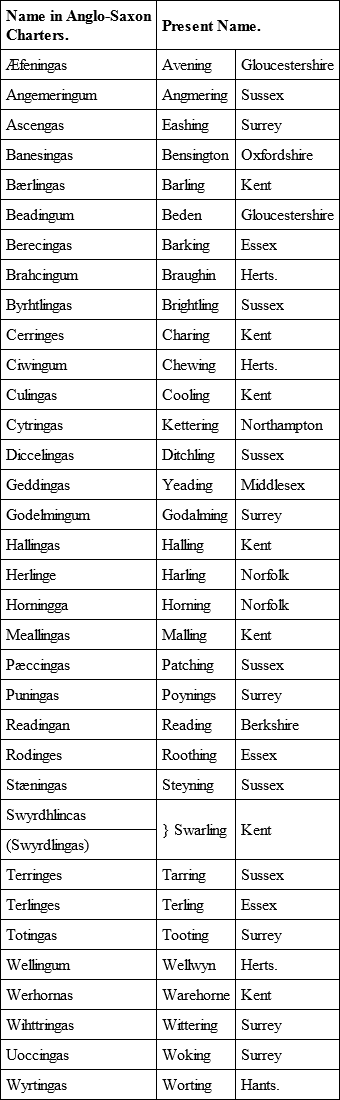

In connection with this subject, it may be of interest to present a list of existing names of places formed from an Anglo-Saxon personal name, as derived from the same ancient charters dealt with in the previous list. And in so doing I confine myself exclusively to the places of which the present names have been positively identified by Mr. Kemble. And in the first place I will take the place-names which consist simply of the name of a tribe or family unqualified by any local term whatever.

I will now take the places which in a later and more settled time have been derived from the name of a single man, as representing his dwelling, his domain, or in not a few cases his grave.

1. Or Cyneburg; see p. 71.

2. It seems clear from the names collated by German writers that ramn, remn, and ram in ancient names are contractions of raven. Compare the names of the ports, Soderhamn, Nyhamn, and Sandhamn, for, no doubt, Soderhaven, Nyhaven, and Sandhaven.

The last name, Windsor, is an amusing instance of the older attempts at local etymology. First it was supposed, as being an exposed spot, to have taken its name from the "wind is sore;" then it was presumed that it must have been a ferry, and that the name arose from the constant cry of "wind us o'er" from those waiting to be ferried across. It was a great step in advance when the next etymologist referred to the ancient name and found it to be Windelsora, from ora, shore, (a contraction of ofer?) Still, the etymon he deduced therefrom of "winding shore" is one that could not be adopted without doing great violence to the word; whereas, without the change of a letter, we have Windels ore, "Windel's shore," most probably in the sense of landing-place. The name Windel forms several other place-names; it was common in ancient times, and it has been taken to mean Vandal. I refer to this more especially to illustrate the importance of taking men's names into account in considering the origin of a place-name.

The above names are confined entirely, as I have before mentioned, to the places that have been positively identified by Mr. Kemble. And as these constitute but a small proportion of the whole number, the comparison will serve to give an idea of the very great extent to which place-names are formed from men's names.

CHAPTER VI.

CORRUPTIONS AND CONTRACTIONS

Corruptions may be divided broadly into two kinds, those which proceed from a desire to improve the sound of a name, and those which proceed from a desire to make some kind of sense out of it. The former, which we may call phonetic, generally consists in the introduction of a letter, either to give more of what we may call "backbone" to a word, or else to make it run more smoothly. For the former purpose b or p is often used – thus we have, even in Anglo-Saxon times, trum made into trump, sem into semp, and emas into embas. So among our names we have Dumplin, no doubt for Dumlin (O.G. Domlin), Gamble for Gamel, and Ambler for Ameler, though in these names something of both the two principles may apply. In a similar manner we have glas made into glast in Glæstingabyrig, now Glastonbury (p. 88). So d seems sometimes to be brought in to strengthen the end of a word, and this, it appears to me, may be the origin of our names Field, Fielding, Fielder. The forms seem to show an ancient stem, but as the word stands, it is difficult to make anything out of it, whereas, as Fiell, Fielling, &c., the names would fall in with a regular stem, as at p. 50. So also our name Hind may perhaps be the same, assuming a final d, as another name, Hine, which, presuming the h not to be organic, may be from the unexplained stem in or ine, as in the name of Ina, King of Wessex. In which case Hyndman might be the same name as Inman. Upon the same principle it may be that we have the name Nield formed upon the Celtic Niel. So also f appears to be sometimes changed for a similar purpose into p, as in Asprey and Lamprey for Asfrid (or Osfrid) and Landfrid. The ending frid commonly becomes frey (as in Godfrey, Humphrey, Geoffrey), and when we have got Asfrey and Lanfrey (and we have Lanfrei in the Liber Vitæ), the rest is easy.