полная версия

полная версияThe Old Riddle and the Newest Answer

There are other creatures which stand in solitary isolation, with no fragments of a bridge to connect them with the general body. Such is the rattlesnake's family, whose pedigree, Mr. Mivart declares,261 we cannot even imagine – "The ancestors of the rattlesnake are beyond our mental vision."

But the number of forms [says the same author]262 represented by many individuals, yet by no transitional ones, is so great that only two or three can be selected as examples. Thus those remarkable fossil reptiles, the Icthyosauria and Plesiosauria, extended, through the secondary period, probably over the greater part of the globe. Yet no single transitional form has yet been met with in spite of the multitudinous individuals preserved. Again, with their modern representatives the Cetacea, one or two aberrant forms alone have been found, but no series of transitional ones indicating minutely the line of descent. This group, the whales, is a very marked one, and it is curious, on Darwinian principles, that so few instances tending to indicate its mode of origin should have presented themselves. Here, as in the bats, we might surely expect that some relics of unquestionably incipient stages of its development would have been left.

Professor W. C. Williamson likewise remarks263 on these lacunæ which persistently occur at crucial points:

If [he writes] these generic types [of plants] first came before us in such clearly defined forms, when and where did the transitional states make their appearance? The extreme evolutionists constantly affirm of those who believe in special creation that they "habitually suppose the origination to occur in some region remote from human observation," and that "the conception survives only in connexion with imagined places where the order of organic phenomena is unknown." It is legitimate to retort upon them that they as habitually resort to "strata now covered by the sea" – to rocks "from which all traces of such fossils as they probably included have been obliterated by igneous action," and to mysterious "migrations from pre-existing continents to continents that were step by step emerging from the ocean." Unfortunately, so far as the vegetable kingdom is concerned, we have as yet failed to discover any traces of these mysterious strata or hypothetical continents in which the transitions from one plant-type to another were being brought about. The believers in special creations are not the only reasoners who have made free use of hypothetical possibilities.

He presently adds:

We have no evidence that unaided Nature has produced a single new type during the historic period. We can only conclude that the wonderful outburst of genetic activity which characterized the Tertiary age was due to some unknown factor, which then operated with an energy to which the earth was a stranger, both previously and subsequently. The knowledge of this factor is what we need in order to perfect our philosophy; and until we obtain that knowledge, many things must remain unaccounted for, so far as primeval vegetation is concerned.

And elsewhere Professor Williamson reiterates the same idea:264

I contend stoutly [he says] that, however numerous may be the facts that sustain the doctrine of evolution (and I am prepared to admit that there are many that do so in a remarkable manner), this unexplained outburst of new life demands the recognition of some factor not hitherto admitted into the calculations of the evolutionist school.

In the record of fossil fishes he finds some features which are particularly hard to harmonize with any theory of genetic evolution.265 Amongst the very earliest representatives of this class, even in the upper Silurian, are found remains of sharks, in his opinion the highest order of fish, and in the Devonian and Carboniferous above, of Ganoids armour clad, like the sturgeon. But nowhere below the Chalk do we find a single scale of Cycloids or Ctenoids, which in regard alike of the scales themselves, of the nervous system and of the reproductive organs, are much below the sharks, and not above the Ganoids. To complicate matters still more, however, the skeleton of Cycloids and Ctenoids is more highly organized than that of the others, and it is thus equally impossible to describe them as progressive or as retrogressive types.266

Over and above this absence of intermediate or link forms, the witnesses who have been cited insist on the fact that those earliest found are not simple or generalized representatives of their respective types, as the theory of genetic evolution requires them to be, but are as perfectly finished and specialized as those appearing in later ages. To their testimony on this point may be added that of Professor Huxley, who while frankly confessing that he would be glad enough to find evidence in favour of such progressive modification, was constrained by his love of scientific truth to bear witness as follows:267

The only safe and unquestionable testimony we can procure – positive evidence – fails to demonstrate any sort of progressive modification towards a less embryonic, or less generalized type, in a great many groups of animals of long-continued geological existence. In these groups there is abundant evidence of variation – none of what is generally understood as progression; and if the known geological record is to be regarded as even any considerable fragment of the whole, it is inconceivable that any theory of a necessarily progressive development can stand, for the numerous orders and families cited afford no trace of such a process.

So again he declared at a later period268 summarizing what he had said previously:

In answer to the question, What does an impartial survey of the positively ascertained truths of palæontology testify in relation to the common doctrines of progressive modification?.. I reply: It negatives these doctrines; for it either shows us no evidence of such modification, or demonstrates such modification as has occurred to have been very slight; and as to the nature of that modification, it yields no evidence whatsoever that the earliest members of a long-existing group were more generalized in structure than the later ones.

He went on, however, to say, on this latter occasion, that discoveries made in the interval afforded much ground for softening "the Brutus-like severity" which eight years before he had exhibited in this regard, by disclosing such evidence as he had declared to be lacking. From the samples, however, which he produced, it does not appear that this fresh testimony comes to very much; and in view of the observations with which he accompanied the exposition, it would seem that in only one instance did it appear to himself thoroughly satisfactory.

Every fossil [he said]269 which takes an intermediate place between forms of life already known, may be said, so far as it is intermediate, to be evidence in favour of Evolution, inasmuch as it shows a possible road by which Evolution may have taken place. But the mere discovery of such a form does not, in itself, prove that Evolution took place by and through it, nor does it constitute more than presumptive evidence in favour of Evolution in general.

It is easy270 to accumulate probabilities – hard to make out some particular case in such a way that it will stand rigorous criticism. After much search, however, I think that such a case is to be made out in favour of the pedigree of the Horse.

Of this famous instance we have already heard, and since it will be examined at length in the following chapter, we will not dwell further upon it here.

So obvious indeed is this deficiency for evolutionary requirements of the Geological record, that Professor Haeckel attempts to supply the want by boldly interpolating a number of periods during which the metamorphoses occurred, but of which no record was left. He assumes that between the epochs of depression, when fossils were deposited beneath the water, there were other epochs of elevation when the land was dry and no deposits could occur, and he supposes that the abrupt changes of flora and fauna exhibited by successive formations, are due to the lapse of time of which we have no organic record in what he styles these "Ante-periods."

As to this summary mode of loosing the Gordian knot, it will be sufficient to quote Professor Huxley's verdict: "I confess this is wholly incredible to me."271 And although in his favourable review of Haeckel's book272 he showed himself far more tolerant of gratuitous speculations, than his utterances on other occasions might have led us to expect, upon this point he declared: "I fundamentally and entirely disagree with Professor Haeckel."

We may sum up the testimonies of which the above are representative in the words of two authorities by no means hostile to Evolution. M. Edmond Perrier,273 having shewn how this theory is suggested by the successive developments of type, and how the phenomena of organic life seem to harmonize with it, thus continues:

Unfortunately, when we descend to details, such palæontological gaps present themselves that every sort of objection is possible. The chain which morphology has allowed us to piece together is continually snapped when we essay to travel back into the past… The art of distinguishing realities from phantoms of the imagination is what has made modern science so great and so mighty. She is strong enough to win honour by avowing ignorance, and because men see her always determined to speak the truth, they gradually realize that she is not dangerous.

And in his Presidential address to the Linnean Society, May 24, 1902, Professor S. H. Vines thus expressed himself as to the genealogical table of organic life, which ever since the doctrine of Evolution was accepted, it has been sought to construct:

Though here and there fragments of the mosaic seem to have been successfully pieced together, the main outlines, even, of the great picture are as yet but dimly discernible.

The fact that organic Evolution should have proceeded so far as it has within such limits of time as may reasonably be allowed, admits, to my mind, of no other interpretation than that variation is not indeterminate, but, as Lamarck and Nägeli have urged, there must exist in living matter a certain inherent tendency or bias in favour of variation in the higher direction. It is this tendency or bias that I venture to regard as the primordial factor.

But it is precisely such an inherent tendency of organic life to develop on predetermined lines, which Darwinians and other advocates of Evolution by the agency of physical forces alone, vehemently repudiate as fatal to their whole system.

[Since Professor Williamson wrote, the opinion has been adopted that for the very reason which induced him to place the Sharks above the Cycloids and Ctenoids, their relative positions should be reversed. The Sharks being a more "generalized" type, with features more akin to those of land-dwelling reptiles, and the others more "specialized" for purely aquatic conditions, the latter, it is argued, are a higher evolutionary product. As a necessary corollary it is assumed that vertebrate life originated, not, as had been supposed, in the sea, but in swamps or lagoons on the shore-line. It must, however, remain a question how far the facility with which theories can thus be modified according to requirements, is calculated to inspire confidence in them.]

XVII

"AUDI ALTERAM PARTEM"

WE have heard Mr. Carruthers' declaration, based upon his survey of palæontological botany, "The whole evidence is against Evolution, and there is none in favour of it."

Remarkably enough, at almost the same period274 Professor Huxley concluded a discussion of palæontological evidence with a precisely contrary pronouncement – "The whole evidence is in favour of Evolution, and there is none against it." On other occasions, also, he distinctly maintained that it is just this line of enquiry which conclusively establishes Evolution as no longer a theory, but an historical fact. To such a conclusion, he tells us,275 "an acute and critical-minded investigator is led by the facts of palæontology;" – and, again, "If the doctrine of Evolution had not existed, palæontologists must have invented it, so irresistibly is it forced upon the mind by the study of the remains of the Tertiary mammalia."

Such declarations clearly challenge consideration, especially when it is remembered how strict were the views which Professor Huxley professed as to the necessity of proofs for our beliefs, – "that it is wrong for a man to say he is certain of the objective truth of any proposition unless he can produce evidence which logically justifies that certainty."276

We therefore turn naturally to his lectures on Evolution, wherein he treats the palæontological argument ex professo, and we find that his verdict is based upon a few selected instances, such as that of the reptilian birds already mentioned, which he considers favourable to Evolution, and one which he terms demonstrative, – namely that of the Horse. This he treats in some detail; in regard of it he delivers the positive judgment which we have just heard, and it therefore in a special manner demands our attention.

As furnishing evidence for the history of the horse, two features are of special importance, his limbs, and his teeth. Of these we may confine our attention to the former, as being, at once, sufficient for our purpose, and within the scope of ordinary observation.

The horse family, or Equidae, belong to the tribe of Ungulates, or hoofed animals, some points of whose anatomy require to be considered in relation to our own.

Taking first the fore-limbs. What we call the "knee" of a horse is in reality the wrist, – the true knee, or rather elbow, being what we call the "shoulder." Below the knee comes the "cannon bone," corresponding to the middle bone of the hand, and below it the "pastern," "coronary," and "coffin" bones, representing the joints of the solitary middle-finger, while the hoof is its greatly enlarged and thickened nail. Similarly, in the hind-limbs; the "hock" is veritably the ankle, and again the lateral digits are suppressed, the middle toe alone remaining.

It thus appears that an Ungulate such as the horse, is an extreme modification of the general Mammalian plan, his members being highly specialized for a certain kind of work. His leg and hoof, as the theory of genetic Evolution declares, have been gradually fashioned to their present shape from an original limb in the common Mammalian ancestor, which by other modifications has equally produced the totally different members possessed by other mammals.

That the horse is descended from a race bearing more than one digit on each extremity, seems to be indicated by the splint-bones which are found on the cannon-bone of both fore and hind legs, and which represent the second and fourth finger and toe, and also by recorded occurrences of polydactyle horses, one of which has a distinguished place in history as Julius Cæsar's charger.277

That the animal as we now know him is the lineal descendant of various other ungulates, in whom the digits were gradually reduced from the normal number of five, to their present solitary representative, Professor Huxley and other Evolutionists hold to be demonstrated by the discovery in due succession of various equine specimens, in which this diminution is gradually exhibited.

The remains of these animals are all found in Tertiary strata, of which, it will be remembered, there are three great divisions, the Eocene, Miocene, and Pliocene, the first named being the most ancient, and the last the most recent.

The genus Equus, or at least our modern horse, Equus caballus, can be traced no further back than the Post-tertiary period. The succession of forms leading up thither commences at the bottom of the Eocene, and extends to the upper Pliocene.

Following Professor Huxley's guidance, we trace the pedigree downwards, thus:

Firstly, there is the true horse. Next we have the American Pliocene form, Pliohippus. In the conformation of its limbs it presents some very slight deviations from the ordinary horse. Then comes Protohippus, which represents the European Hipparion, having one large digit and two small ones on each foot… But it is more valuable than Hipparion, for certain peculiarities tend to show that the latter is rather a member of a collateral branch, than a form in the direct line of succession. Next, in the backward order in time, is the Miohippus, [Miocene], which corresponds pretty nearly with the Anchitherium of Europe. It presents three complete toes – one large median and two smaller lateral ones; and there is a rudiment of that digit which answers to the little finger of the human hand. The European record stops here: in the American Tertiaries, the series of ancestral equine forms is continued into the Eocene. An older Miocene form, Mesohippus, has three toes in front, with a large splint-like rudiment representing the little finger, and three toes behind. The radius and ulna, tibia and fibula,278 are distinct. Most important of all is the Orohippus, from the Eocene. Here we find four complete toes on the front limb, three toes on the hind-limb, a well developed ulna, a well developed fibula.

Here, when the lecture which we are considering was delivered, the series terminated: – and upon the facts as above given Professor Huxley thus commented:

Thus, it has become evident that, so far as our present knowledge extends, the history of the horse-type is exactly and precisely that which could have been predicted from a knowledge of the principles of Evolution. And the knowledge we now possess justifies us completely in the anticipation, that when the still lower Eocene deposits, and those which belong to the Cretaceous Epoch have yielded up their remains, we shall find, first, a form with four complete toes and a rudiment of the innermost or first digit in front, with probably a rudiment of the fifth digit in the hind foot; while, in still older forms, the series of the digits will be more and more complete, until we come to the five-toed animals, in which, if the doctrine of Evolution is well founded, the whole series must have taken its origin.

Finally he was able to add in a note that since the delivery of the lecture, Professor Marsh had discovered a new genus of Equine Mammals, Eohippus, corresponding very nearly to his description of what might first be looked for. "This," adds Professor Huxley, "is what I mean by demonstrative evidence of Evolution… In fact, the whole evidence is in favour of Evolution, and there is none against it."

That these facts are indeed most remarkable and deserving of all attention, cannot be questioned. But before we can agree that they are conclusive and demonstrative in Professor Huxley's sense a good many considerations require to be carefully weighed.

(i.) It is obvious, in the first place, that here as in all other instances which we have seen, the one thing is lacking which is really wanted in order to prove Evolution, namely evidence of one species gradually shading off into another. The creatures of which we have heard, are each isolated from the rest, and indeed very much isolated, for each belongs to a different genus,279 which shows that the differences between them are substantial. They are, in fact, farther apart from one another, than the zebra or the donkey from the horse, for both of these are classed in the genus equus, – or than the Bengal tiger is from the domestic pussy-cat, both belonging to the genus felis.

These various ungulate forms thus stand a long way from one another, and if they were once connected together by a bridge, or rather a causeway, we ought certainly to find some traces of it, and not always of those particular types which require to be united. If we suppose the very distinct species actually known to have been the piers of such a bridge, yet what has become of the arches? Till some vestiges of these be found, or, at least, some positive evidence that arches there actually were, can it be said that the story of the fossil equidae furnishes convincing testimony on behalf of the supposed evolution? Affinities these various forms undoubtedly exhibit: it has yet to be shown that affinities necessarily imply descent.

There is, however, something even more remarkable. We have seen that Professor Huxley prognosticated beforehand the discovery of Eohippus, and specified pretty nearly the features it would be found to present. In the same way, Professor Marsh280 anticipates and describes a still more remote ancestral form, for which, though it has not yet been found, he has provided an appellation, Hippops. But if either Professor really believes in Evolution, why does he take for granted that we shall chance upon one particular form, standing like a solitary outpost by itself, and not upon any other trace of the stream of life whereof it was but one transient phase? Such predictions may be evidence that the occurrence of these progressive forms is regulated by something analogous to Bode's Law of interplanetary distances, and that their discovery may be looked for at certain intervals. But the very fact that their actual position can be so accurately specified serves to show that it is very definitely fixed.

(ii.) Moreover, a very grave difficulty at once suggests itself, of which Professor Huxley makes no mention. The horse as we now have him, Equus caballus, is a native of the Old World, and has been introduced to America only since the time of Columbus. There had, it is true, been horses in America previously, – belonging to the genus Equus, perhaps even to the species caballus, – they had, however, been long extinct, and no memory of them remained. But, as will be noticed, the pedigree given by Professor Huxley consists almost entirely of American animals, to which category belong all whose names terminate in -hippus, and these cannot with any reason be assigned as progenitors to the European horse. As Sir J. W. Dawson observes:281

In America a series of horse-like animals has been selected, beginning with the Eohippus of the Eocene – an animal the size of a fox, and with four toes in front and three behind – and these have been marshalled as the ancestors of the fossil horses of America… Yet all this is purely arbitrary, and dependent merely on a succession of genera more and more closely resembling the modern horse being procurable from successive Tertiary deposits often widely separated in time and place. In Europe, on the other hand, the ancestry of the horse has been traced back to Palæotherium– an entirely different form – by just as likely indications, the truth being that as the group to which the horse belongs culminated in the early Tertiary times, the animal has too many imaginary ancestors. Both genealogies can scarcely be true, and there is no actual proof of either. The existing American horses, which are of European origin, are, according to the theory, descendants of Palæotherium, not of Eohippus; but if we had not known this on historical evidence, there would have been nothing to prevent us from tracing them to the latter animal. This simple consideration alone is sufficient to show that such genealogies are not of the nature of scientific evidence.

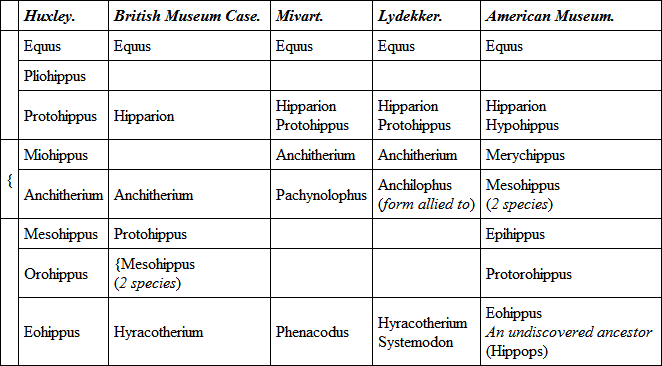

(iii.) Even apart from this fundamental difficulty, there is much diversity as to the precise genealogy. We may compare together the lines of ancestry favoured – (1) by Professor Huxley, (2) In a case exhibited in our Museum of Natural History to illustrate the subject, (3) By Mr. Mivart,282 (4) By Mr. Lydekker,283 (5) In The Evolution of the Horse, a pamphlet issued, January, 1903, by the American Museum. This last gives the very latest version of the pedigree, but, naturally, of the American Horse alone.

It will be observed, that whereas Hipparion is disallowed by Professor Huxley as not being in the direct line of descent, in all the other genealogies he appears as the immediate ancestor of Equus. Also that in all these tables, Old World and New World forms are used indifferently to supply progenitors for the same successor. Also that there is no agreement at all as to the earlier ancestry. It would likewise appear that even the existence of Eohippus himself is not beyond question, for in our Museum galleries and guide-book his name always has a note of interrogation appended. The American authorities give an anticipatory sketch of the limbs of the ancestor which still remains to be discovered.