Полная версия

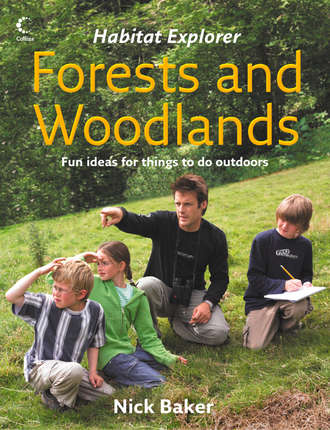

Forests and Woodlands

For my wild friend Ceri, a small token of my appreciation of you. You saved me!

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

The wildlife in woodland

Handy stuff for exploring with

The tree canopy

Is your wood ancient?

Keep a tree log

Make leaf lace

The texture of bark

How old is your tree?

Profiling your tree

Whistling in the wood

Grow your own giant

The understorey

Budding brilliant

Mapping territories

Talk with the birds

Nests and holes

Make your own nest

Hedge your bets

Seed watching!

The herb layer

See the light

Rabbit hunting

How to hide yourself

Brock watch

Know your cones

Spore points

The litter layer

Signs and reading them right

Nuts - who has nibbled them?

The fungus among us

Boring beetles

Galling

Little jumpers

Going further

Index

Author’s Acknowledgements

Keep Reading

Copyright

About the Publisher

The wildlife in woodland

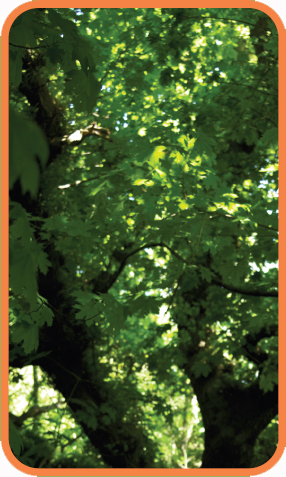

Looking up through the bright green, newly unfurled leaves of a beech woodland, you may feel like you are in a huge cathedral gazing up through the stained glass windows – ones that are made up of many shades of green. But we chop these trees down, use them as crops or as things to climb. Woodlands are places to walk the dog, they form barriers and boundaries but they are the lungs of the planet.

Trees are amazing light machines. Just like other plants, they trap the Sun’s energy by using it to combine water and carbon dioxide gas in the air to form sugars. But trees do it on a much bigger scale. Each one is a light factory, with tiny microscopic work stations inside each leaf. While looking up through the canopy, hold a leaf in your hand and imagine the scale of production. Think of the millions of little cells in the leaf and then multiply by the number of leaves you can see all around you. Just half a hectare of woodland is such an effective factory that it produces over 6,000 tonnes of roots, wood and leaves every year!

To smaller beasts, a field of grass is like a forest, but a forest, wood or copse is a unique experience for human-sized creatures. This is exactly what this book is about: exploring our woods, forests, hedgerows and some of the habitats that are associated with them.

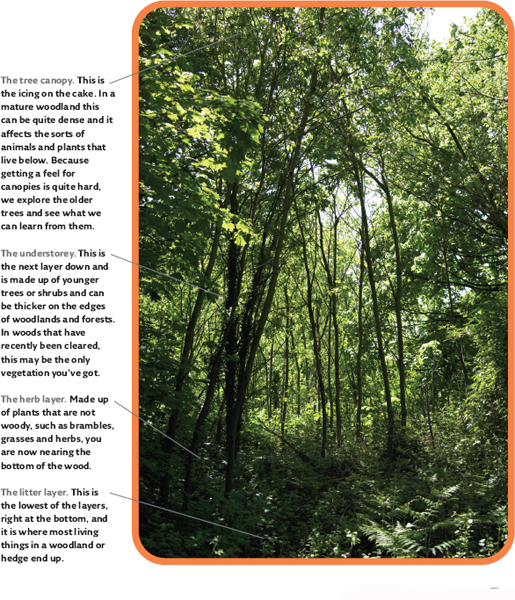

The book is divided into chapters that roughly reflect the different levels of woodland. Imagine the woodland as if it was a layer cake. If you were able to take a slice through it, you would see a pattern to the apparent tangled mass of life.

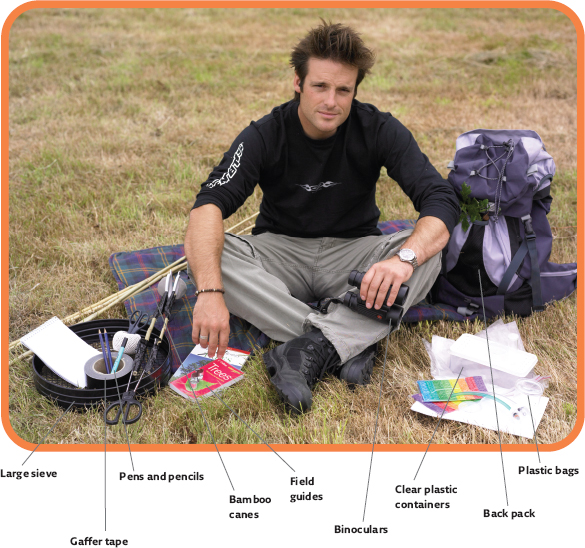

Handy stuff for exploring with

As a youthful naturalist with, I assume, little pocket money, you will be relieved to know that when it comes to specialist equipment, there really isn’t much needed! Most can be put together and constructed or improvised from items found under the sink, in the shed or under the stairs. In fact, the most important tools you need to learn to use are your own senses; but more about that later. For now, though, here is a short list of things that I find useful in an everyday kind of way when exploring woodland.

Bamboo canes These are handy things for many of the activities in this book and they are useful for creating an extention to your arms! You can tape a wire hook to the end and use it to bend down branches that were otherwise out of your reach or use it to beat branches that are in your way.

Binoculars and magnifying lens Anything with a lens in it to magnify little things or bring distant subjects closer is going to be a relatively expensive bit of kit compared with the rest of the equipment you might have with you. But if you can possibly afford it, they are really worth investing in and there are many different kinds at prices to suit all sizes of pocket.

Clear plastic containers These can be anything from purpose-made specimen tubes to old 35mm film canisters and empty jam jars. They are handy for collecting and observing specimens in. Plastic bags are also very useful and have the added advantage of being lightweight and folding flat in your pocket.

Field guides Always handy, but if you take good notes, they can be consulted once you have got home and so save you space in your pockets or your day pack.

Gaffer tape Many of the things you build or construct in this book use this wonderful stuff. It is also excellent for making repairs and quick fixes.

Pen and paper (notebook) It is a very useful skill to record your observations, never mind how seemingly insignificant they may be. All the best naturalists do it.

Sieve Useful for panning through leaf litter and soil. This is one of the best ways to find the over-wintering pupae of many moth species.

Back pack Finally, you need something to put all this stuff in! Make sure it’s large enough to carry everything, but that it’s not so heavy it spoils a day out in the woods.

The tree canopy

A tree on its own is never a tree on its own. Trees act like a life magnet. You can have a plain bare patch of grass with nothing much in the way of wild life hanging around. But stick a tree in the middle of it and it’s a whole different story. Birds will perch in it and may nest there, insects will find it attractive and nibble or even breed in it. As the tree gets bigger, it creates more living space for even more life.

Making an inventory of a tree near you is always a fun thing to do, and would be a great idea for a personal project or something you can do at school. Try to count as many living things as you can, from the microscopic algae that give the cracks in the bark a greenish tinge, to the birds and mammals that visit. You will be very surprised at what you find.

But just imagine what happens when you stick a collection of these incredible trees together! The effect is magnified, which is why woodlands are such amazing places to explore and why some people make such a fuss when they get removed.

This chapter is about the trees themselves – what they are, how they live and grow. Get to know the trees and you will begin to understand and love the heart of the wood itself.

Fab facts

Here are some BIG numbers for the big European oak:

* 40 hectares of woodland can support 300–400 birds.

* 30 different types of lichen have been found on the bark of these trees.

* 200 species of moth live on the leaves.

* 45 true bugs suck its juices and stalk other prey among its branches.

* 65 mosses and liverworts can be found on the bark.

* 40 species of galls have been found on oak trees.

An oak apple or gall may end up on the woodland floor, but while it’s alive, it grows much further up a tree, near the tree canopy.

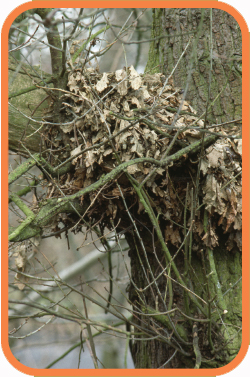

A grey squirrel’s drey, neatly perched high in the canopy.

The dappled sunshine emerging through the tree canopy is always a cheering sight.

Is your wood ancient?

Many woodlands have been a feature of our landscape for a long time while others have been cleared and have either been re-colonized or re-planted. While all woodlands offer shelter and food for certain creatures, those that have been around for longer tend to have a greater number of species. This variety of species is called biodiversity.

In the spring, investigate your local woodland. Is it ablaze with colour, as a carpet of plants explode into flower and leaf? There is only a brief window of warmth and light in a wood before the leafy canopy closes over and returns most of the wood floor into the dappled half light. This is why so many plants in the understorey have broad leaves (see also opposite).

We humans have real trouble thinking outside of our own life expectancy. We tend to think that we have had a good innings if we get to 80 years old, but most trees at 80 have barely got going. Living at a slower speed than us is part of their fascination. As long-lived plants, they have their own stories to tell. They are like living history lessons, telling us about their own lives and the conditions to which they were exposed as they grew.

Get to know some of the truly old trees in your area. Work out their age (see pages 18–19 and the Take it further box, opposite) and learn about their history; perhaps relate it to famous historical events in human history, such as wars and invasions. You will soon get a sense of what events these trees may have stood through. This is the first step to tree appreciation and helps you to enjoy them fully. You can also maybe help a little by planting a few of your own (see pages 24–5).

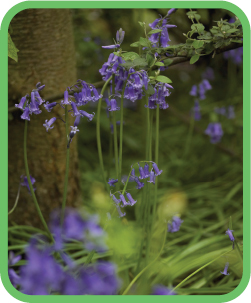

Look closely at many spring-flowering plants. They have large, broad leaves designed to steal as much of the sparse light that falls on them as possible. Many also grow in large and dense mats, a sign that they reproduce and spread mainly by bulb splitting and underground runners, rather than by seeding. The fact that they spread like this means they tend to be specialized at surviving in woodlands but are next to useless at spreading to new locations. As a result, they take many years to colonize a woodland.

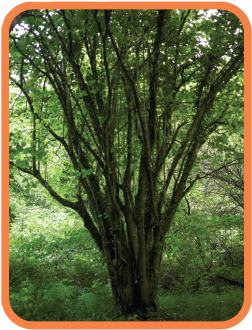

Woods were once used as a crop and their products were used in day-to-day life. Look for multi-trunked trees that seem to grow from a thick and gnarly old base. These may well have been coppiced at some time. This is the process of harvesting the straight poles that sprout from a cut stump. Some of these would be used for building poles or for making hurdles or fences, while others would be burnt to produce charcoal for smithies and home fires. Today, coppicing still goes on in some woods.

Take it further

* Other clues to the age and use of a woodland or hedgerow can be found by looking for tell-tale traces of how man has managed them.

* Old woods tend to have uneven and curved boundaries while new ones are usually straighter.

* Plants are another great way to tell if a woodland is ancient. Look for:

Bluebell

Wood anemone

Pignut

Wild garlic

Wood sorrel

Dog’s mercury

Cow wheat

Primrose

Wild daffodil

Early dog violet

Keep a tree log

Starting to identify trees can be a little daunting. Some of them are easier to tell apart. For example, conifers have cones and needles and they keep their leaves all year round. Deciduous trees have big flat leaves that turn brown, yellow and red and fall off in the winter. But learning about trees in more depth can be difficult. To help, make your own tree log. This is an excellent way to collect as much information as possible about the trees in your area, and you can start at pretty much any time of the year.

The first characteristic to look for in your tree is the shape of the leaves. Each species has its own very distinctive leaf pattern. Most are instantly recognizable from this quality alone, although there are a few that you may find a little tricky, such as hornbeam and elm, and a few of the exotic species introduced from other countries, but you will soon get the hang of the main native species.

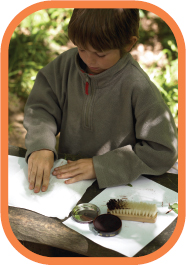

Start by collecting a selection of leaves, either from the ground or directly from the tree itself. Once you have these leaves back at home there are several ways you can incorporate them into your log – start with the ideas opposite and more are given on the following pages. You can then move onto exploring the bark (see pages 16–17), seeing how old it is (pages 18–19) and drawing its profile (pages 20–21).

To make your tree log, use a scrap book or collect some loose pages or some clear plastic pockets. You can keep adding to your file as you find more information and evidence.

YOU WILL NEED

> leaves

> sticky tape

> watercolour paint

> paintbrush

> paper

> shoe-cleaning brush

> shoe polish

> blotting paper

1 Use your leaf like a stencil. Place it on paper and fix the stem with sticky tape.

2 Carefully paint over the leaf, just going over its edges. Let it dry.

3 Slowly lift the leaf and, hey presto!, you are left with a perfect outline of your leaf.

4 You can also use a stiff brush to apply some dark shoe polish to one side of your leaf. Dead leaves that have fallen from a tree work best for this approach as they are stronger and more rigid.

5 When it is well covered, turn the leaf over and press it firmly onto a plain sheet of paper to leave an imprint. Press some blotting or kitchen paper over this to sop up any oily residues.

Make leaf lace

If you have been sifting around in the bottom of a pond or ditch, you may occasionally stumble across a stunningly beautiful phenomenon – that of a leaf that has had all the soft parts nibbled away to leave a net-like web of veins. These veins are all that is left of the leaf’s plumbing. The tubes and pipes are what the sap of the plant flows through, carrying essential chemicals around the plant’s body.

There is a rather simple and fun way of recreating this effect to order. Not only are they a beautiful thing to have in your tree log but they can also be mass produced, painted and used in many creative ways, such as on a collage picture and to decorate cards.

Nick’s trick

* Pressing leaves is the same as pressing flowers. You can either use a professional flower press – a stacked sandwich of alternating cardboard and blotting paper between two boards with bolts in each corner – or you can use a heavy book or two to weight down the layers.

* The most important thing is to place your leaf between some absorbent material like blotting paper or kitchen towel. Sheets of plastic will also stop any plant sap from oozing out and ruining your book cover or pages.

* Change the blotting paper every other day and after a week or so your leaves will be preserved. I like to store mine in individual plastic envelopes with a label on the outside of each one saying what it is and where the trees were growing.

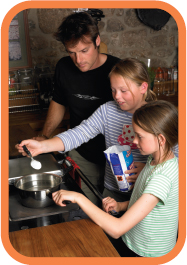

YOU WILL NEED

> leaves

> washing soda

> a pan of water

> a soft paint brush

1 Fill your pan with water and add about 2 dessert spoons of washing soda for every 500ml of water.

2 Place the pan on a gentle heat until it is simmering, then take the pan away from the heat and place your leaves in the solution.

3 Leave them submerged for a good 30 minutes, making sure all of the leaves are under the surface. Then gently wash the leaves with fresh water by placing the pan under a slowly running cold tap, letting the water flush out the soda mixture and soft debris.

4 You should now be left with beautiful transparent leaves. To remove the soft material surrounding the veins, place the leaves on a saucer and gently brush with an artist’s paintbrush. Leave to dry on some kitchen towel.

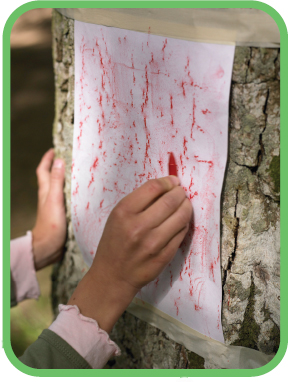

The texture of bark

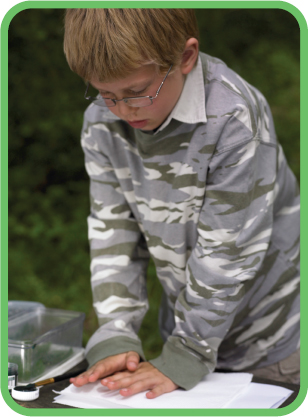

Another distinguishing feature of a tree, and one that remains even in the winter when most leaves would have dropped, is the texture of the bark. The quickest and easiest way to record this is to make a rubbing – see Nick’s trick, below. The other way of recording your tree requires a little more effort, but it produces a really smart, three-dimensional model of a section of tree trunk – and that is by making a cast of it (see opposite).

Hold the crayon or pastel on its side for the most effective technique. This really helps to bring out the textures underneath.

Nick’s trick

* Carefully tape a piece of paper to the trunk of the tree and then colour over it with a crayon or pencil (dark looks best on white paper, but white chalk on black paper is pretty stylish, too).

* In this way you record all those textures and patterns and soon you will start to recognize a combination of these features and the colours. I have a friend who is a blind naturalist and he can tell most species of tree by these very textures you will be recording with your rubbings.

YOU WILL NEED

> modelling clay

> strong cardboard box

> plaster of Paris

> water

> poster paints

> paintbrush

1 First find the tree you wish to make an impression of. Then knead and pummel your modelling clay so it is soft and free of air bubbles. This makes it much easier to work with and gives you a better impression at the end.

2 Firmly press the clay into the tree’s surface. Try to keep the clay at least 1.5cm thick and aim to keep the edges from tapering. If you are going to make many such casts for a collection, use standard dimensions at this point as it makes the casts easier to store and/or mount.

3 Peel away the clay and you will notice all the bark textures on it. You now have to get this home without damaging the mould, so this is where a stout box to transport the clay comes in handy.