полная версия

полная версияStories of Useful Inventions

(Copyright 1911 by Underwood & Underwood, N. Y.)

FIG. 16. – ELEVATOR ARCHITECTURE.

The tower-like structure in the distance is a building more than forty stories in height.

Thus we may see in the house of to-day a long and unbroken story. Where the roof is flat it is Egyptian; where it slants gently in two directions it is Greek; where it is steep or sharply pointed it is Gothic. The columns are Greek, the rounded arches are Roman. The whole is the result of the thousands of years of effort which man has given to the task of providing for himself a safe, convenient and beautiful home.

THE CARRIAGE

We are very proud in our day of our means of transportation. If one wishes to send a present to a friend a thousand miles away a few cents spent in postage will take the article to its destination. If for the sake of higher prices a fruit grower wishes to sell his crops in a distant city, the railroad people will haul it for him at a very small cost. If you wish to visit a friend in town several blocks away, there is the electric car ready to take you for a nickel. If your friend is several hundred miles away, the steam car will take you in a few hours at a cost of not more than two or three cents a mile. I am living in the country sixteen miles from the city in which my work lies, and for nine cents I am carried to the place of my business in less than half-an-hour. What has been the history of the inventions which make transportation so comfortable, rapid and cheap? Our subject divides itself into two parts, transportation on land and transportation on water or the story of the Carriage and the story of the Boat. We will have the story of the carriage first.

FIG. 1. – A HUMAN BURDEN BEARER.

(From a Model in National Museum.)

Man's only carriage at first was of course his own feet. When he wanted to go to any place he had to take "Walker's hack," if a playful expression may be pardoned. As a traveler on foot, man soon surpassed all other animals. He could walk down the deer and wear out the horse. When it came to carrying things from place to place, in the beginning he had to rely upon his own limbs and muscles. It was not long, however, before he learned that there were good ways and bad ways of carrying things, and he soon set about finding the best way. We may believe that he began by making a snug bundle and carrying it on his shoulder. Then he found that he could carry a heavier burden upon his back, and he invented a pack or frame on which he could carry things on his back (Fig. 1) after the manner of one of our modern pack peddlers.

FIG. 2. – A SHIP OF THE DESERT.

In the course of time man tamed one or more of the wild beasts which roamed near him. Then the burden was shifted from the back of a man to the back of a beast. The first beast of burden in South America was the llama; in India it was the elephant; in Arabia it was the camel (Fig. 2). In Europe and in parts of Asia and in Egypt the horse first became man's burden bearer and the nations which had the services of this swift and strong animal outstripped the other nations of the world. "Which is the most useful of animals?" asked one Egyptian god of another. "The horse," was the reply, "because the horse enables a man to overtake and slay his enemy."

FIG. 3. – A CART WITHOUT WHEELS.

(From a Model in the National Museum.)

It is often easier to drag a thing along than it is to carry it. This fact led to the invention of what we may call the first and simplest form of carriage. This was the drag or travail (tra-vay´), a cart without wheels (Fig. 3). Two long saplings were fastened at the large end to the strap across the horse's breast and the small end upon which the burden was placed dragged upon the ground. Mr. Arthur Mitchell in his delightful book, "The Past in the Present," tells us that he saw carts of this kind in actual use in the highlands of Scotland as late as 1864! An improvement upon the travail was the sledge made of the forked limb of a tree (Fig. 4). This primitive sledge was really a travail consisting of one piece.

FIG. 4. – A PRIMITIVE SLEDGE.

(From a Model in National Museum.)

FIG. 5. – THE FIRST CART.

FIG. 6. – HAULING TOBACCO.

(From a Model in National Museum.)

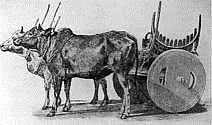

In many cases it is easier to roll a thing than it is to drag it. This fact led to another step in the development of the carriage; it led from the cart without wheels to a cart with a wheel – a most important step in the history of inventions. The first wheeled cart was simply a log from each end of which projected an axle (Fig. 5). The axle fitted in the holes of a frame upon which the body of the cart was placed and to which the horse or the ox was attached. As the cart moved along, wheel (log and axle) turned together. The very ancient method of moving a load by rolling it along was in use in the United States not so very long ago. As late as 1860 in some of the southern States hogsheads of tobacco (Fig. 6) were rolled over country roads in the manner just described and as late as 1880 the fishermen of Nantucket used as a fish cart a vehicle that had only a barrel for its wheel. (Fig. 7.) The common wheel-barrow and the one-wheeled carts which are still used in China and Japan had their origin in the rolling log.

FIG. 7. – A NANTUCKET FISH CART.

(From a Model in the National Museum.)

FIG. 8. – A CART WITH WHEELS AND AXLE IN ONE PIECE.

FIG. 9. – CART WITH A SOLID WHEEL.

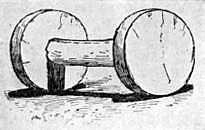

We are told by some writers that the rolling log (the one-wheeled cart) was followed by the two-wheeled cart, on which the wheels were the ends of a log and the axle was the middle portion of the log hewn down to a proper size (Fig. 8). Here wheels and axle turned together precisely like a modern car wheel. This makes a very pretty story but I am afraid the solid two-wheeled affair represented in Figure 8 is only imaginary, and that in a true account of the development of the cart it has no place. The true beginning of the two-wheeled cart may be learned from Figure 9. Here the wheels are two very short logs through the center of which are holes in which the round ends (axles) of a piece of timber (the axle-tree) fit. When the cart moves, the wheels turn upon the axle. The one-wheeled cart had at first one log turning with the axle; the two-wheeled cart at first had as its wheels two very short logs turning on the axles.

FIG. 10. – CART WITH WHEEL PARTLY SOLID.

(From a Model in the National Museum.)

FIG. 11. – WHEELS WITH SPOKES.

(From National Museum.)

FIG. 12. – AN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN CHARIOT SHOWING HUB, SPOKES, FELLY AND RIB.

(From National Museum.)

The first two-wheeled carts were a great improvement upon the single rolling log, yet they were exceedingly heavy and clumsy. The trouble was with the wheel. This was very thick and with the exception of the hole in which the axle went it was entirely solid. Wheelwrights at a very early date saw that the problem was to make the wheel light and at the same time to keep it strong. Little by little this problem was solved. At first crescent-shaped holes were made in the wheel (Fig. 10). This made the wheel lighter, but did not weaken it. In its next form the wheel was even less solid than before. It now consisted of four curved pieces of wood (Fig. 11) held together by four spokes. In this wheel there was a hub, but the spokes were not inserted in it; they were fastened about it. In the Egyptian chariot (Fig. 12) we find the wheel in the last stage of its interesting and remarkable development. Here the spokes, six in number, are inserted in the hub from which they radiate to the six pieces of the felly or inner rim. Around the felly is the outer rim or tire made of wood and fastened to the felly with thongs. The wheel of to-day has more iron in it, and has more spokes and is lighter and stronger than the old Egyptian wheel, yet in its main features it is made like it.

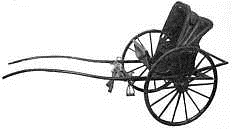

FIG. 13. – WONDERFUL ONE HOSS SHAY.

(From National Museum.)

A light running two-wheeled carriage was used by all the civilized nations of the ancient world. Three thousand years ago in the great and wicked city of Nineveh chariots raced up and down the paved streets "jostling against one another in the broad ways, with the crack of the whip, the rattle of the wheel and the prancing of horses." The chariot played an important part in the life of the Greeks and Romans, in their racing contests and in their wars, and throughout the Middle Ages it was the only vehicle in general use in Europe. As time passed it was of course made lighter and stronger and better. The doctor's gig so charmingly described by Holmes in his "Wonderful One Hoss Shay" may be taken as an illustration of the full development of the two-wheeled carriage (Fig. 13).

FIG. 14. – AN ANCIENT ROMAN CHARIOT.

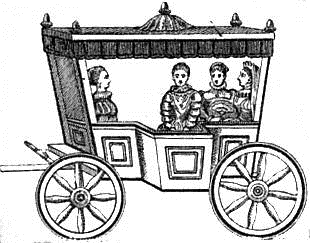

FIG. 15. – A COACH OF THE MIDDLE AGES.

Bring the hind part of one Egyptian chariot opposite to the hind part of another, lash the two chariots together, remove the tongue of one of the chariots and you have made a chariot of four wheels or a coach. The form of the most ancient of four-wheeled carriages leads to the belief that the coach was first made by joining together two two-wheeled chariots in the way just described. The ancient Egyptians had their four-wheeled chariots but only their gods and their kings had the privilege of riding in them. For centuries none but the great and the powerful rode in coaches. The Roman chariot (Fig. 14), bad imitations of which we see nowadays in circus processions, was used only in the splendid triumphal processions which entered Rome after a great victory. In the Middle Ages we get a glimpse of a four-wheeled carriage now and then, but usually the king or a queen is lounging in it (Fig. 15). The coach could not be generally used in Europe in medieval times because the roads were so bad. The excellent roads made by the Romans had not been kept in good condition. Traveling had to be done either on horseback or in the two-wheeled carriage. In 1550 there were but three coaches in Paris and in London there was but one. In 1564, however, we find Queen Elizabeth riding in a coach (Fig. 16) on her way to see her lover, Lord Leicester. Insert more spokes and lighter ones in the wheels of this coach of the queen's, put on rubber tires and mount the body on elliptical springs17 and we will have the coach of to-day.

FIG. 16. – QUEEN ELIZABETH'S COACH.

THE CARRIAGE

Continued

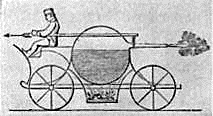

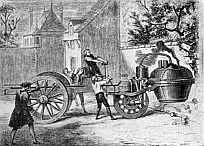

FIG. 1. – NEWTON'S STEAM CARRIAGE, 1680.

FIG. 2. – CUGNOT'S STEAM CARRIAGE, 1769.

In the last chapter the story of the Carriage was brought up to the reign of Queen Elizabeth of England. In the century following Elizabeth's reign a new and most remarkable step in the development of the carriage was taken. You remember that in the seventeenth century there was a great deal of experimenting with steam (p. 58). Among other experiments was one made by Sir Isaac Newton. This great philosopher tried in 1680 to make a steam-carriage, or locomotive, as we call it. Figure 1 shows the principle upon which he tried to make his carriage work. The steam was to react against the air, as in the case of Hero's engine (p. 56) and thus push the carriage along. Newton's experiment was not satisfactory but the idea of a steam-carriage was now in men's heads and the hope of making one continued to be cherished. In 1769 Cugnot, a French army officer, invented a steam-carriage of three wheels (Fig. 2) but it was a very poor one. It traveled only three or four miles an hour, it could carry but three persons, and it had to stop every ten minutes to get up steam. Cugnot, however, deserves to be ranked among the great inventors for he showed that a steam-engine could be attached to a carriage and could push it along. In other words he showed that steam could be used for transportation as well as for working pumps and turning the wheels of factories. And that was just what was needed most in the latter part of the eighteenth century. Man needed assistance in traveling; he especially needed help in carrying things from place to place. The steam-engine was keeping the mines dry and making it possible to mine great quantities of coal and was turning the wheels of great factories where the spinning-jenny and the new power loom (p. 119) were consuming enormous quantities of cotton and wool. Now if the steam-engine could also be made to carry the coal and cotton and wool to the factory, and the manufactured products from the factory to the market, the industrial revolution would be complete indeed.

Inventors everywhere put their wits together to construct an engine that would draw a load. The great Watt tried to make one, but having failed, he came to the conclusion that the steam-engine could do good work only when standing still. Among those who entered the contest was Richard Trevithick, a Cornish miner, born in 1771. Trevithick when a lad at school was able to work six examples in arithmetic while his teacher worked one. He proved to be as quick in mechanics as he was in mathematics. He began his experiments with steam when a mere boy, and as early as 1796 he had built a steam-locomotive which would run on a table. By 1801 he had constructed a steam-carriage (Fig. 7). Three years later (1804) Trevithick exhibited a locomotive which carried ten tons of iron, seventy men, and five wagons a distance of nine and one-half miles at the rate of five miles an hour. This was the first steam carriage that actually performed useful work. The honor of inventing the first successful locomotive, therefore, belongs to Richard Trevithick, although he never received the honor that was due him.

FIG. 3. – STEVENSON'S LOCOMOTIVE, 1828.

FIG. 4. – THE "BEST FRIEND." THE FIRST LOCOMOTIVE BUILT FOR ACTUAL SERVICE IN THE UNITED STATES.

The honor went to George Stephenson, of Wylam, near Newcastle, England. Stephenson's parents were so poor that they could not afford to send him to school long enough for him to learn to read and write. In his eighteenth year, however, he attended a night school and learned something of the common branches. In his childhood Stephenson lived among steam-engines. He began as an engine boy in a colliery and was soon promoted to the position of fireman. At an early age he was trying to build the locomotive that the world needed so badly, one that would do good work at a small cost. Trevithick's locomotive was too expensive. Stephenson wanted a locomotive that would pay its owner a profit. At the age of thirty-three he had solved his problem. In 1814 he exhibited a locomotive that would run ten or twelve miles an hour and carry passengers and freight cheaper than horses could carry them. Eleven years later he was operating a railroad between Stockton and Darlington, England. The steam carriage was now a success (Fig. 3). The iron horse was soon transporting passengers and freight in all the civilized countries of the world (Fig. 4). Observe that the first passenger car was simply the old coach joined to a locomotive.

FIG. 5. – A TROLLEY CAR.

The locomotive worked wonders in travel and in carrying loads, yet men were not satisfied with it. We never are satisfied with our means of transportation. No matter how comfortably or cheaply or fast we may travel we always want something better. In the latter part of the nineteenth century the great cities of the world were becoming over-crowded. The people could not be carried from one part of a city to another without great discomfort. The street cars drawn by horses could not carry the crowds and the elevated steam cars were not satisfactory. Wits were set to work to relieve the situation and about thirty years ago the electric car (Fig. 5) was invented. Without horse or locomotive this quick-moving car not only successfully handles the crowds which move about the city but it also relieves over-crowding by enabling thousands to reach conveniently and cheaply their suburban homes. It also does the work of the steam car and carries passengers long distances from city to city.

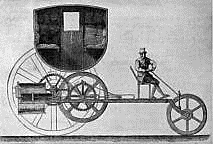

FIG. 6. – A HORSELESS CARRIAGE OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

FIG. 7. – THE FIRST AUTOMOBILE.

FIG. 8. – GOOD-BY TO THE HORSE.

A late development in carriage making is seen in the automobile. As far back as the sixteenth century a horseless carriage was invented (Fig. 6) and was operated on the streets of a German city. But here the power was furnished by human muscle. The first real automobile (Fig. 7) was invented in 1801, by the man who invented the first successful locomotive. Trevithick's road locomotive – for that is what an automobile really is – did not work well because the roads upon which he tried it were in very bad condition. Inventors after Trevithick for a long time paid but little attention to the road locomotive; they bestowed their best thought upon the locomotive that was to be run upon rails – the railroad locomotive. In recent years, however, they have been working on the so-called automobile and they have already given us a horseless carriage that can run on a railless road at a rate as great as that of the fastest railroad locomotives. To what extent is this newest of carriages likely to be used? It is already driving out the horse. Will it also drive out the electric car and the railroad locomotive? Are we coming to the time when the railroad will be no more and when all travel and all hauling of freight will be done by carriages and wagons without horses on roads without rails? The answers to these questions can of course only be guessed.

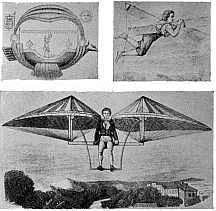

FIG. 9. – SOME UNSUCCESSFUL FLYING MACHINES OF A HUNDRED YEARS AGO.

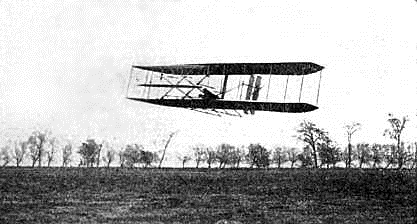

The last and latest form of the carriage is seen in the flying-machine, the automobile of the air. In all ages men have watched with envy the movements of birds and have dreamed of flying-machines, but only in modern times has man dared to take wings and glide in bird-like fashion through the air. The first actual flying by a human being was done by a Frenchman named Bresnier, who, in 1675, constructed a machine similar to that shown in the right hand picture at the top of Figure 9. Bresnier worked his wings with his feet and hands. Once he jumped from a second story window and flew over the roof of a cottage. From the days of Bresnier on to the present time man has taxed his wits to the utmost to conquer the air, and in his efforts to do this he has invented almost every conceivable kind of machine. About the middle of the nineteenth century inventors began to apply steam to the flying-machine, and it is said that in 1842 a man named Philips was able, by the aid of revolving fans driven by steam, to elevate a machine to a considerable distance and fly across two fields. In 1896 Professor Langley, with a flying-machine driven by a small steam-engine, made three flights of about three-fourths of a mile each over the Potomac River, near Washington. This was the first time a flying-machine was propelled a long distance by its own power; it was the first aerial automobile. But the aerial steam carriage was never a success; the steam engine was too heavy. In the early years of the twentieth century inventors began to use the light gasoline engine to drive their flying-machines and then real progress in the art of flying began, and so great has been that progress that the automobiles of the air are becoming rivals of those on the land.

FIG. 10. – A SUCCESSFUL FLYING MACHINE OF TO-DAY.

THE BOAT

FIG. 1. – THE FIRST BOAT.

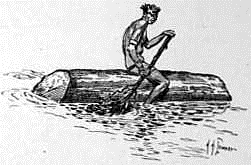

FIG. 2. – THE INVENTION OF THE CANOE.

At first, when a man wanted to cross a deep stream, he was compelled to swim across. But man at his best is a poor swimmer, and it was not long before he invented a better method of traveling on water. A log drifting in a stream furnished the hint. By resting his body upon the log and plashing with his hands and feet he found he could move along faster and easier. Thus the log was the first boat and the human arm was the first oar. Experience soon taught our primitive boatman to get on top of the log and paddle along, using the limb of a tree for an oar (Fig. 1). But the round log would turn with the least provocation and its passenger suffered many unceremonious duckings. So the boatman made his log flat on top. It now floated better and did not turn over so easily. Then the log was made hollow, either by burning (Fig. 2), or by means of a cutting instrument. Thus the canoe was invented. Very often if the nature of the tree permitted it, the log was stripped of its bark, and this bark was used as a canoe.

FIG. 3. – THE RAFT – SHOWING ALSO EARLY USE OF THE SAIL.

FIG. 4. – A PRIMITIVE OARLOCK.

The canoe was one of the earliest of boats, but it is not in line with the later growth. The ancestry of the modern boat begins with the log and is traced through the raft rather than through the canoe. By lashing together several logs it was found that larger burdens could be carried. Therefore the boat of a single log grew into one of several logs – a raft (Fig. 3). By the time man had learned to make a raft he had learned something else: he had learned to row his boat along by pulling at an oar instead of pushing it along with a paddle. But in order to row there must be something against which the oar may rest; so the oarlock (Fig. 4) was invented. Rafts were used by nearly all the nations of antiquity. Herodotus, the father of history, tells us that they were in use in ancient Chaldea. In Figure 3 we have a kind of raft that may still be seen on some of the rivers of South America. Here a most important step in boat-building has been taken. A sail has been hoisted and one of the forces of nature has been bidden to assist man in moving his boat along.