полная версия

полная версияStories of Useful Inventions

FIG. 7. – AN OLD AFRICAN LOOM.

In the old African loom represented in Fig. 7 we find several improvements upon the loom of the Pueblo woman. In the first place, it has two heddles instead of one. These are operated by the feet, leaving the hands free to do other work. In the second place, the wooden frame which the weaver holds in his right hand is not to be seen in the Pueblo loom. This frame called the batten, or lathe, contains the reed, which is a series of slats or bars between which the threads of the warp pass after they leave the heddle. When the weaver has thrown the weft through the shed he brings the batten down hard and the reed drives the last weft thread close to the woven part of the cloth. The reed takes the place of the sword-like stick used by the Pueblo woman. Last and most important: in the African's left hand is the shuttle, or little car – weaver's ship, the Germans call it – which carries the weft across (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8. – A PRIMITIVE SHUTTLE.

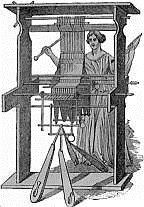

FIG. 9. – A LOOM OF THE SIXTEENTH CENTURY.

The loom described above seems to be clumsy and rude when compared with a loom of the present day, yet it is really the kind of loom which was used by nearly all civilized people from the dawn of their civilization to the middle of the eighteenth century. It is the loom of history and poetry and song. Upon a loom of this kind was woven Joseph's coat with its many colors and the garment which the fair Penelope made when she deceived her suitors. Of course as the centuries passed the parts of the loom were better made and weavers became more skilful. In Figure 9 we have the loom as it appeared in the sixteenth century. If we inspect it closely we shall find it to be merely the old African loom mounted on stout upright timbers instead of being mounted on a tripod made of poles. With her feet the weaver works the heddle, with her right hand she throws the shuttle, with her left she draws toward her the swinging batten and drives the weft home with the reed.

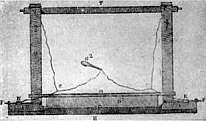

FIG. 10. – KAY'S FLYING SHUTTLE.

The year 1733 is a most important date in the development of the loom for in that year John Kay, a practical loommaker of Lancashire, England, invented the flying shuttle and thus did more for the loom than any man whom we can distinguish by name. To appreciate the great service of Kay we must recall how the shuttle was operated before his time. You remember it was thrown through the shed by one of the weaver's hands and caught and returned by the other hand. Sometimes it was caught and returned by a boy. This was at best a slow process and unless the weaver had an assistant to return the shuttle only narrow pieces could be woven. The common width of cloth, three-fourths of a yard, had its origin in necessity. The weaver's arms were not long enough to weave a wider piece. "The essence of Kay's invention was that the shuttle was thrown from side to side by a mechanical device instead of being passed from hand to hand. One hand only was required for the shuttle while the other was left free to beat up the cloth (with the batten) after each throw, and the shuttle would fly across wide cloth as well as narrow." You will be able to understand Kay's invention by studying Figure 10 which shows how the flying shuttle worked. G is a groove (shuttle-race) on which the shuttle runs as it crosses through the shed leaving its thread behind it. I and I are boxes which the shuttle (Fig. 11) enters at the end of the journey. In each box is a driver K sliding freely on the polished rod F. The weaver with his right hand pulls the handle H and K drives the shuttle to the opposite side. With his left hand he works the reed, with his feet he works the heddle.

FIG. 11. – A MODERN SHUTTLE.

The profits of Kay's invention were stolen, his house was destroyed by a mob and he himself was driven to a foreign country where he died in poverty. Yet he deserves high rank among the benefactors of mankind, for the flying shuttle doubled the power of the loom and improved the quality of the cloth woven. Kay's invention was the first step in a great industrial revolution. The increased power of the loom called for more yarn than the old spinning wheel could supply. Hargreaves and Arkwright set their wits to work and made their wonderful spinning machine, and the demands of the loom were supplied. So great was the supply of yarn that the hand loom was behind with its work. Then in order to keep up with the spinning machine the power-loom was invented. Heddle and batten and shuttle were now driven by a force of nature and all the weaver had to do was to keep the shuttle filled with thread and see that his loom worked properly. At first the water-wheel was used to drive the power-loom but later the steam-engine was made to do this work. All this was changing the face of the civilized world. Hitherto weavers and spinners had worked for themselves in their homes or in their own shops; now they were gathered in large factories where they worked as wage earners for an employer. Hitherto industry had been carried on in small villages; the great factories drew the people to large industrial centers and the era of crowded cities began.

FIG. 12. – THE JACQUARD LOOM.

Following the invention of the power-loom in the latter half of the eighteenth century came the invention of Joseph Jacquard of Lyons, France. This very ingenious man in 1801 invented a substitute for the heddle. We cannot readily understand the workings of Jacquard's wonderful "attachment," as his substitute for the heddle is called, but we ought to know what the great Frenchman did for the loom. In Figure 12 you see that the cloth which is exposed shows that beautiful designs have been woven into it. This is what Jacquard did for the loom. He made it weave into the cloth whatever design, color or tint one might desire. He made the loom a mechanical artist rivaling in excellence the work of a human artist. The Jacquard loom has brought about a revolution in man's, and especially in woman's dress. With the old loom, colors and designs could be woven into cloth but only very slowly, and goods with fancy patterns were made at a cost that was so great that only the rich could afford to buy. In the olden times, therefore, almost everybody wore plain clothes. With Jacquard's attachment the most beautiful figures can be cheaply woven into the commonest fabrics. As far as weaving is concerned, it costs no more to have beautiful figures in cotton goods than it does to have them in silk. As a result the poor as well as the rich can dress as their taste and fancy may suggest.

The last century brought improvements in the weaving art as every century before it brought improvements, but the changes made since Jacquard's time need not concern us. The story of the loom ends with the Jacquard "attachment." Perhaps no other of man's inventions has a more interesting development than the loom. We can see it grow, piece by piece. First a simple stick from which dangle the threads of the warp; then the heddle, then the shuttle, then the reed, then the shuttle-race and the swiftly flying shuttle, and last the Frenchman's wonderful device for weaving in colors and fancy figures.

THE HOUSE

Man has always been a builder. Like squirrels and beavers and birds he provides himself a home as by instinct. The kind of house erected by a people in the beginning depended upon the surroundings, upon the enemies that prowled about, upon the climate, upon the building materials close at hand. In a hilly, rocky region primitive folk built one kind of house, in a forest they built another kind, in a low marshy district they built still another kind. In all cases they took the materials that were the easiest to get and erected the kind of dwelling place that would afford the greatest safety and comfort.

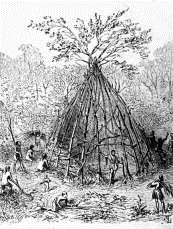

FIG. 1. – BUILDING A HOUSE WITH WOOD.

If one could have traveled over the earth during the first days of man's history one would doubtless have found that dwellings were made of wood, for in those days the greater part of the earth was covered with forests. To build a home in the forest was the simplest of tasks. All that was necessary was to fasten together the tops of several saplings, interlace the saplings with boughs (Fig. 1) and cover the frame with skins of animals or thatch it with leaves and grass. A cone-shaped structure of this pattern, a tent, or hut, or wigwam, was the first house of all primitive people who lived where there was plenty of wood.

FIG. 2. – A CAVE-DWELLING.

In many regions, especially in parts of northwestern Europe, the wigwam or hut was not always the most suitable dwelling place for early man. In hilly and mountainous districts and along streams where shores were overhung by rocks or pierced by caverns the first inhabitants found that a hollow in the earth was the best kind of house. Sometimes the house of the cave-dwellers was made by Nature (Fig. 2); sometimes it was an artificial living-place dug in the side of a hill or mountain. The cave was truly a rude and gloomy home, yet there was a time when large numbers of the human race lived in caves. The Zuni Indians of Arizona in seeking a refuge from their enemies built their homes far up in steep cliffs where it was almost impossible for a stranger to go.

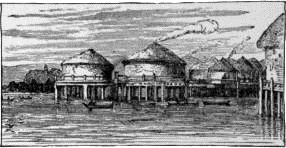

FIG. 3. – LAKE-DWELLINGS, RESTORED.

(From Troyon.)

Coming down from the highlands to the lowlands where there were swamps and marshes or where inland lakes were numerous, we find that the first houses were built upon piles driven in the water or in the mud (Fig. 3). These lake-dwellings, as houses of this kind were called, were generally connected with the mainland by gangways of wooden piers, although sometimes they could be approached only by boat. In the floors of some of these curious dwellings were trapdoors through which baskets could be lowered for catching fish in the lake below. The children of the lake-dwellers were tethered by the feet to keep them from falling into the water. The beautiful city of Venice in its infancy was a community of lake-dwellers. The rough canoe of the lake-dwelling time has developed into the graceful gondola, and the rude wooden pier has grown to be the magnificent Rialto.

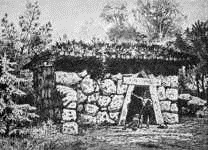

FIG. 4. – A PRIMITIVE STONE HOUSE.

In many regions the most convenient building material is stone and all over the earth there are proofs to show that building with stone began at a very early date. The stones in the earliest stone structures were rough and unhewn and were laid without mortar or cement (Fig. 4) yet they were sometimes fitted together with such nicety that a thin knife blade could not be passed between them. Remains of stone houses built many thousands of years ago may be seen in Peru, Mexico, Italy, and Greece. These primitive dwellings were humble and simple, but they were made of good material and they were well built. They have weathered the storms of ages and they have remained standing while later and more pretentious buildings have crumbled and disappeared.

The illustrations of early building which have been given will make plain the truth that the people of a particular country have taken the materials nearest at hand and have constructed their homes according to their particular needs. Now since the beginnings of house building have been different in different parts of the earth, the story of the house will not be the same in all countries. In China and Japan, where the light bamboo has always flourished and has always been used in building, the house has had one development; in countries where granite and marble and heavy timber abound it has had another and an entirely different development. What then is the story of the house as we see it in our country? Can this story be told? As one passes through an American city looking at the public buildings and churches and stores and dwellings can one go back to the beginning and trace step by step the growth of the house and tell how these came to be what they are? Let us see if this cannot be done.

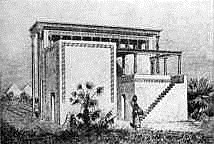

FIG. 5. – AN EGYPTIAN HOUSE.

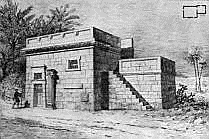

FIG. 6. – AN ANCIENT HEBREW DWELLING.

FIG. 7. – INTERIOR OF AN ANCIENT EGYPTIAN PALACE.

Our story takes us back many thousands of years to Egypt, the cradle of civilization. From Egypt it will take us to Greece, thence to Rome, thence to the countries of Northern Europe, thence to America. What kind of houses did the Egyptians first build? They built as simple a structure as can be imagined; they erected four walls and over these they placed a flat roof (Fig. 5). The roof was made flat because in Egypt there is scarcely any rain and there was no need for a roof with a slant. In all those countries where rain seldom falls, or never falls, the flat roof is the natural roof (Fig. 6). Although their buildings were simple in construction the Egyptians left behind them most remarkable specimens of the builder's art. Their pyramids and monuments and sphinxes and palaces have always been foremost among the great wonders of the world. Figure 7 shows the interior of an ancient Egyptian palace. This palace had only an awning for a roof. That was all that was necessary to keep out the rays of the sun. Notice the lofty pillars or columns of this building. You see they are adorned above or below with the figure of the lotus, the national flower of the Egyptians. The column, as we shall see, plays an important part in the history of the house and it was ancient Egypt that gave the world its first lessons in the art of making columns.

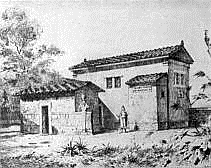

FIG. 8. – A GREEK DWELLING.

From Egypt we pass over "the sea" to Greece. The Greeks borrowed ideas wherever they could and in the matter of architecture they borrowed heavily from Egypt. But they did not borrow the flat roof of the Egyptians. In Greece there was some rainfall and this fact had to be taken into account when building a house; the roof had to slant so that the rain could run off. Now the Greeks taught the world the best way to make a slanting roof. They made the roof to slant in two directions from a central ridge (Fig. 8) instead of having the entire roof to slant in one direction like an ugly shed. The slant was gentle because there was no snow to be carried off. The roof of two slants formed a gable. The Greeks, then, were the inventors of the gable. The column they borrowed from Egypt. But whenever the Greeks borrowed an invention or an idea they nearly always improved upon it. Instead of slavishly imitating the Egyptian columns they tried to make better ones and they were so successful that they soon became the teachers of the world in column making.

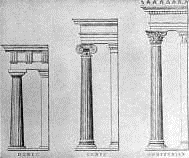

FIG. 9. – THE THREE ORDERS OF COLUMNS.

The oldest and strongest of the Greek columns belong to what is known as the Doric order (Fig. 9), a name given to them because they were first made by the Dorians, the original Greek dwellers in Europe. Aside from the flutes or channels which ran throughout its length the Doric column was perfectly plain. In the older Doric columns even the flutes are absent. Its capital or top, was without ornament. Later the graceful and elegant Ionic pillar (Fig. 9) came into fashion. We can always distinguish an Ionic column by the volute or scroll at its capital. The latest of the Greek columns was the Corinthian (Fig. 9), the lightest, the most slender and the most richly decorated of all. A cluster of acanthus leaves at its capital is the most prominent ornament of the Corinthian column. The Greeks carried the art of column making to such perfection that even to this day we imitate their patterns. A column in a modern building is almost certain to be a Greek column. It is worth one's while, therefore, to be able to tell one Greek column from another. One can do this by remembering (1) that the Doric column is perfectly plain and has no capital; (2) that the Ionic column has a scroll at the capital; (3) that the capital of the Corinthian column is adorned with a cluster of acanthus leaves.

FIG. 10. – AN OLD ROMAN ARCH.

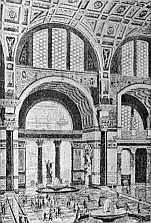

FIG. 11. – INTERIOR OF A ROMAN CLUB HOUSE.

Our story now takes us to Italy. Greece fell before the power of Rome 146 B.C., but before she fell she had taught her conquerors a great deal about architecture. Indeed the Romans took up the art of building where the Greeks left it. They needed the Greek gable for they had rains, and the Greek column recommended itself to them on account of its beauty. They used the best features of Grecian architecture and added a feature that was largely their own. This was the arch. The Greeks, like the Egyptians before them, bridged over the openings of doors and windows and the spaces between columns by means of straight wooden beams or long blocks of stone. The Romans bridged over these spaces with the arch (Fig. 10). If you will study the arch you will see that it is a curved structure which is supported by its own curve. You will also see that it is a structure of great strength. The greater the weight placed upon it, providing its bases are supported, the stronger it gets. In teaching the world how to make arches Rome added to the house an element of great strength and beauty. With the arch came the tall building. In Greece a house was never more than two stories high. In Rome arch rose upon arch (Fig. 11); the dome which is itself a kind of arch appeared and palaces were piled story upon story until they seemed to reach the skies.

FIG. 12. – A DWELLING IN NORTHERN EUROPE.

From Italy we pass to northern Europe. The power of Rome fell 476 A.D., but before that date the greater part of Europe had been Romanized, and the Roman way of building with column and arch and dome had been learned in France and Germany and England. But the climate of those countries was different from that of Italy and a slight change in the Roman way of building was necessary. In the northern countries there were heavy rains and snows and a roof with a gentle slope was not suitable for carrying off large quantities of water and snow. A gable (Fig. 12) with a sharp slant was necessary. Hence throughout northern Europe the roofs were built much steeper than they were in Italy and Greece, although in other respects the northern houses resembled more or less closely those of the older southern countries.

FIG. 13. – POINTED STYLE.

Typical scheme of a fully developed French cathedral of the 13th century. (From Viollet-le-Duc's "Dict. de l'Architecture.")

The pointed roof which was made necessary by the climate of the north prepared the way for a new style of building, the pointed or Gothic style. This style began to appear in the twelfth century and by the end of the thirteenth century – that remarkable century again – the buildings of all northern Europe were Gothic. The new style began with a change in the arch. The Roman arch was a semi-circle and was therefore described from one center. The Gothic arch was formed by describing it from two centers instead of one and was therefore a pointed arch. As the pointed arch grew in favor it became the fashion to shape other parts of the building into points wherever it was possible to do this. The rounding dome became a spire "pointing heavenward"; the windows and doors were pointed and so were the ornaments and decorations. For several centuries buildings fairly bristled with points (Fig. 13). The finest example of Gothic architecture is the glorious cathedral at Cologne.

FIG. 14. – A RENAISSANCE DWELLING.

During the thousand years of the Dark Ages (476-1453) the glories of the civilization of ancient Greece and Rome faded almost completely from human vision. Events of the sixteenth century brought those glories again into view and Europe was dazzled by them. Men everywhere became dissatisfied with the things around them. They longed for ancient things. They read ancient authors, they imitated ancient artists, they imbibed the wisdom of ancient teachers. This was the period of the Renaissance, the time when the world was born anew – as it pleased men to think and say. The world of the present died and the old world of Greece and Rome was brought to life. Of course in the new order of things architecture underwent a change. It was born again; it experienced a renaissance. The pointed style grew less pleasing to the builder's eye, and wherever he could he placed in his building something that was Greek or Roman, here an arched doorway, there a Greek column. There resulted from these changes a style that was neither Gothic, Grecian nor Roman, but a mixture of all these. This mixed style was named after the period in which it arose. When you see a building that strongly resembles the buildings of ancient Greece and Rome and at the same time has features which belong to other styles you may safely say that the building belongs to the renaissance style. (Fig. 14.) The most noble and beautiful examples of renaissance architecture are the church of St. Peter's at Rome and the church of St. Paul at London.

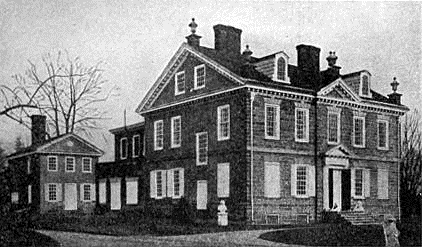

FIG. 15. – A COLONIAL MANSION.

The Cliveden Chew Mansion, where the Battle of Germantown was fought.

We now pass over to America. About the time the old world was born anew the new world was found. The houses of the first settlers in America were of course rude and ugly but as the colonies grew in population and wealth more expensive and beautiful houses were built. As we should expect, the colonists built their best houses in the style that was then in fashion in the old world and that was the renaissance style. They did not, however, copy the old world architecture outright. They had different materials, a different climate and a different class of workmen and they had to build according to these changed conditions. The result was a style of building that has been called colonial (Fig. 15). Colonial architecture was simply American renaissance. And that is what it is to-day. To say that a house is in the colonial style is to say that it represents a certain architect's ideas as to what is best and most beautiful in all styles.

The story of the house really ends with the period of the renaissance. Since the sixteenth century nothing really new in architecture has been discovered and men have been wedded to no particular style. When we want to build a house we choose from all the styles and build according to our tastes. Our story of the house, however, will not be complete without a brief account of what has been called elevator architecture. The high price of land in large cities makes it necessary to run buildings up to a considerable height if they are to be profitable. Now if a building is more than five stories high it must have an elevator, or lift, and if an elevator is to be put in, the building might as well be run up nine or ten stories. American business men learned this thirty or forty years ago and began to build high, and they have been building higher and higher ever since. There are tall buildings in other countries but the "sky-scraper" of twenty-five and thirty stories is found only in the United States (Fig. 16).