полная версия

полная версияA New Catalogue of Vulgar Errors

VI

That exactly under the Æquator is always the hottest Climate on the Globe.

This Error by no Means ought to be called a vulgar one; because it is a Course of Philosophical Study, joined to a Want of Experience, which gives Occasion to it. It is the Result of a Knowledge of the general Cause of Heat and Cold, in different Degrees of Latitude upon the Surface of the Earth; which Knowledge is apt to apply the Rules of Astronomy, that explain the Phœnomena of Nature in general, to every Purpose that offers itself, in all Cases, without being able to search into the individual Parts of a System, on Account of the Distance of the Objects which are the Subjects of Enquiry. For though, as has been said before, for a just Astronomical Reason, the Position will hold good, that those Inhabitants who are under the Line, live in the hottest Climate in general, yet it is proved by the Experience of Navigators, that in several Parts under the Æquator there is a fine, mild, soft Climate, even excelling any of those in the temperate Zones; so happily are Things disposed for the Purposes of Animal Life, by the Author of Nature.

This is a Truth which we are constrained to believe, as we have so many living Witnesses in our own Country, who are ready to assert it.

We have one accurate Account in Anson's Voyage, where the Author reasons very Philosophically upon the Subject. This Author tells us, that the Crew of the Centurion were in some Uneasiness about the Heat of the Climate, which they expected they were to undergo, when they came to that Part of the Æquator which is near the American Coast, upon the South Sea; but that when they came under the Line, instead of those scalding Winds which sometimes blow in immensely hot Climates, they were agreeably surprized with the softest Zephyrs imaginable; and that, instead of being scorched by the perpendicular Rays of the Sun, they had a fine Covering of thin grey Clouds over their Heads, and just enough of them to serve for a Screen, without looking dark and disagreeable. Many other Beauties of the Climate the Author describes, which need not be mentioned here, as it is easy to see the Book.

He accounts for the extraordinary Mildness of the Climate in Words to this Purpose:

"There are Mountains on the Sea Coast of this Latitude, of an enormous Height and great Extent, called the Andes, the Tops and Sides of which are covered with everlasting Snow. These Mountains cast a Shade and Coolness round them, for several Leagues, and by their Influence it is, that the Climate is so temperate under that Part of the Line. But, says the Author, when we had sailed beyond the Æquator, into four or five Degrees of North Latitude, and were got out of the Influence of those Mountains covered with Snow, we then began to feel that we were near the Line, and the Climate was as hot as we could have expected to have found it at the Æquator itself."

There can be no Doubt of the Truth of this Account: No Man would have made such Assertions as these, if they had not been true, when there were so many living Witnesses to have contradicted such an idle, needless Falshood as this would have been. And indeed the Appearance of wise Design in the Author of Nature is no where more conspicuous than in these Instances of his Care for the Preservation of the animal System. What could we have expected more than Mountains of Snow in Greenland? And even in those frozen Regions we have as great Instances of the same Providence: When the Springs are all frozen up, in that severe Climate, they have sometimes, even in the middle of Winter, such mild South Winds as serve to thaw the Snow, so as to cause Water to settle in the Valleys, and to run under the Ice in Quantities large enough to serve the Purposes of animal Life; not to mention the great Quantities of Timber which the Surf of the Sea brings upon that Coast, from other Countries; without which the Inhabitants would have no Firing, nor Timber for their Huts, nor Shafts for their Arrows, as there are no Trees in that Country.

And now I hope it will not be thought too bold an Analogy if we presume to say, that as, contrary to all Expectation, at the Æquator (where intolerable Heat might be expected) the Inhabitants are provided with Mountains covered with Snow, to qualify their Atmosphere; why may not we suppose, that at the very Poles themselves there may be some Cause, unknown to us, which may render the Climate serene and mild, even in that supposed uninhabitable Part of the Globe? Why may there not be hot, burning Minerals in the Earth at the Poles, as well as snowy Mountains at the Æquator?

We have Reason to think that the Composition of the Earth, at that Part of the Globe, is of an extraordinary Nature; as the magnetic Quality of it is to be apprehended, from it's immediate Attraction of the Needle. We are entirely ignorant of the Soil, of the Place, and of the Constitution of the Inhabitants, if there are any. We are certain that, near Greenland, there are Sands of so extraordinary a Nature, that the Wind will carry great Clouds of them several Leagues to Sea, and they will fall into the Eyes and Mouths of Navigators, who are sailing past the Coast, at a great Distance. This Instance only serves to shew, that we may be quite ignorant of the Nature of the Soil which is under the Pole; we cannot tell whether it consists of Mountains or Caverns, fiery Volcanos or craggy Rocks, of Ice, Land, or Water, cultivated Fields or barren Desarts.

What has been laid will seem less strange, if we look back into the Notions which the Ancients had of the Torrid Zone. It is not long since it was thought, that only the Temperate Zone on this Side the Æquator was habitable; so far were they from attempting to find out another Temperate Zone beyond the Æquator, that nobody dare approach near the Line, for Fear of being roasted alive. This is the true State of the Case; and if it be so that the Ancients were, for such a vast Number of Years, under a mistaken Notion, concerning the Possibility of living under or near the Line, why may not we, who are neither more daring nor more ingenious than the old Romans, be likewise mistaken, or rather totally ignorant of the Climates at the Pole?

And here I beg Leave to offer a Philosophical Reason, why it should not, according to the Nature of Things, be any colder at the Poles themselves, than ten Degrees on this Side of them. Not that I by any Means insist upon the Truth of what I am going to say; I only just offer it as a Subject to be discussed by those who are more learned, and are able to take more exact Mensurations of the Phœnomena of Nature than myself.

What I would offer is, that there is no Reason to apprehend more Cold at the Extremities of the Poles than ten Degrees on this Side of them, on Account of the Figure of the Earth. The Figure of the Earth is found, by Observations which have been made, upon the Difference of the Vibrations of Pendulums at the Æquator and near the Poles, and by other Experiments, to be not a Sphere, but a Spheroid; it is not exactly round, neither is it oval, but (if I may make Use of the Comparison) more in the Shape of a Turnip.

Now the Climate is hotter at the Æquator than in high Latitudes, on Account of the Inclination of the Poles to the Sun, as has been said before: What I would urge is, that the Surface of the Earth, at ten Degrees on this Side of the Poles, is as much or nearly as much inclined to the Plain of the Ecliptic as the Poles themselves.

If that is the Case, no Reason can be given why the Poles should be colder than Greenland, where, if we may believe the Accounts of Navigators, though in the Winter the Cold is so intense as to freeze Brandy, yet, in the middle of Summer it is sometimes so hot, that People have been glad to strip off their Cloaths, for an Hour or two in a Day, in order to go through their Work. But to return to the Surmise, that the Poles are no colder than ten Degrees on this Side of them, on Account of the Spheroidical Figure of the Earth.

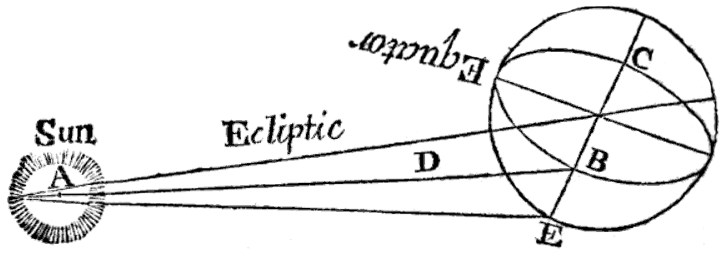

I must trouble the Reader with a very plain Figure, in order to illustrate the Meaning of this.

By this Figure we may observe, that any Rays of the Sun A, which fall upon a Place situated ten Degrees on our Side of the Pole B, and Rays which fall on the Pole itself, do not make so large an Angle, as they would if the Form of the Earth was a Sphere; for if we extend the two Points B and C so far as to make a compleat Sphere, we must be obliged likewise to move the Line D along with it to the Point E, which would make a larger Angle, and in that Case the Surface of the Earth at the Pole B would be more inclined to the Plain of the Ecliptic than it is, and consequently it would be colder, as the Cause of Heat and Cold in different Parts of the Globe is owing to the Inclination of the Poles to the Plain of the Ecliptic, and not to the Distance of the Sun from the Earth at the different Seasons of the Year; for if that was the Case, we should have colder Weather in July than we have in December, the Sun being rather nearer to us in Winter than in Summer.

I hope that this little Philosophical Effort, which has been made here, will not be looked upon as unseasonably introduced in this Place; and I likewise hope, that while I gaze with Wonder on the stupendous Frame of the Universe, I shall not be thought presumptuous in having taken a little Survey of one of the Wheels which duly performs it's Revolutions in that glorious Machine, the Solar System; the exact and regular Movements of which inspire the curious Beholder with a more awful Idea of the Greatness of the Fabricator, than it is possible for any one to conceive, who is entirely ignorant of the Accuracy of the Construction.

VII

That the more Hay is dried in the Sun, the better it will be.

As Hay is an Herb which is dried in order to lay up all the Winter, when it cannot be found in the Fields, and as it is intended for the Food and Nourishment of Animals, that Nourishment must consist of such of the Juices as are left behind in the Herb.

It is very possible, by the Art of Chemistry, to extract from Hay all the separate Salts, Spirits, &c. of which it is composed. Now in a Chymical Preparation, there is always something left behind in the Still, out of which it is impossible to extract any more Juices; that the Chymists call Caput Mortuum. This Caput Mortuum is of no Service, and is entirely void of all those Salts and Spirits with which every other Substance on the Surface of the Earth abounds more or less.

The Sun acts upon Bodies much in the Nature of a Still. He, by his Heat, causes the Vapours of all Kinds, which any Substance contains, to ascend out of their Residences into the Atmosphere, to some little Height, from whence either the Wind carries them, if there is any, or if there is no Wind, they fall down again Upon the Earth by their own Weight, at Sun-set, and are what is called Dew.

Since this is the Case, and the Sun acts upon Bodies in the same Manner as a Still, we should take Care not to make Caput Mortuum of our Hay, by exposing it too long to his Rays; for by that Means we shall extract from it most of those Salts Spirits of which Food must consist, and of which all Animal Substance is composed.

The Botanists are sensible of this: When they dry their Herbs, they lay them in a Place where no Sun can come to them, well knowing that too much Sun would take off their Flavour, and render them unfit for their different Physical Uses. Not that Hay would be made so well without Sun, on Account of the Largeness of the Quantity, and at the same Time it ought to be dryed enough, and no more than enough; for it is as easy to roast Hay too much as a Piece of Meat.

VIII

That the Violin is a wanton Instrument, and not proper for Psalms; and that the Organ is not proper for Country-Dances, and brisk Airs.

This Error is entirely owing to Prejudice. The Violin being a light, small Instrument, easy of Conveyance, and withal much played upon in England, and at the same Time being powerful and capable of any Expression which the Performer pleases to give it, is commonly made Use of at Balls and Assemblies; by which Means it has annexed the Idea of Merriment and Jollity to itself, in the Minds of those, who have been so happy as to be Caperers to those sprightly English Airs, called Country Dances.

The Organ, on the other Hand, being not easily moved on Account of it's Size, and expensive on Account of the complicated Machinery which is necessary to the Construction of it, is not convenient for Country Dances; and at the same Time being loud, capable of playing full Pieces of Music, Choruses, Services, &c. is made Use of in most Churches where the Inhabitants can afford to purchase this fine Instrument.

Nevertheless, notwithstanding these great Advantages, two or three Violins and a Bass, are more capable of performing any solemn Hymn or Anthem than an Organ; for the Violin, as has been before observed, is capable of great Expression, but especially it is most exquisitely happy in that grave and resigned Air, which the common Singing-Psalms ought to be played with. When the Bow is properly made Use of, there is a Solemnity in the Strokes of it, which is peculiar to itself. And on the other Hand, on Account of the Convenience of Keys for the Readiness of Execution, nothing can be more adapted to the Performance of a Country-Dance, than an Organ. For the Truth of which Assertion I appeal to those who have been so often agreeably surprized with those sprightly Allegros, in the Country-Dance Style, with which many Organists think fit to entertain the Ladies, in the middle of Divine Service.

If Jack Latten is played at all, it is Jack Latten still, whether it be played in Church or in an Assembly Room; and I am only surprized, that People can so obstinately persist in the Denial of a Thing, concerning the Truth of which it lies in their Power to be convinced every Sunday.

IX

That the Organ and Harpsichord are the two Principal Instruments, and that other Instruments are inferior to them in a Concert.

Notwithstanding the great Advantage which these Instruments have of playing several Parts together, there is nevertheless one Imperfection which they have, or rather they want one, or more properly a thousand Beauties contained in one Word; which is no less material an Article than that of Expression.

There is no Word more frequently in the Mouths of all Sorts of Performers, than this of Expression; and we may venture to affirm, that it is as little understood as any one Term which is made Use of, in the Science of Music.

Above three Parts in four make Use of it, without having any Meaning of their own, only having heard some one else observe, that such or such a Person plays with great Expression, they take a Fancy to this new adopted Child, and become as fond of it, as if it was the legitimate Offspring of their own Brain. Some who are more considerate, think that the Meaning of it entirely consists in playing Staccato; and indeed these People come nearer the Mark than the others, but they have not picked up all the Meaning of the Word.

One who plays with Expression, is he who, in his Performance, gives the Air or Piece of Music (let it be what it will) such a Turn, as conveys that Passion into the Hearts of the Audience, which the Composer intended to excite by it. Dryden, in that masterly Poem, his Ode in Honour of St. Cecilia's Day, has given us a true Idea of the Meaning of the Word; the Beauties of which Poem, though they are enough to hurry any Man away from his Subject, shall not be discussed at present, not being to the Point in Hand. We shall only make Use of an Instance or two out of it, to illustrate what has been said.

Handel was so sensible of it's being capable, by the Help of Musical Sounds, of raising those very Passions in the Hearts of the Audience, which Dryden fables Alexander to have felt by the masterly Hand of Timotheus, that, by setting it to Music, he has himself boldly stepped into the Place of Timotheus.

In this Performance called Alexander's Feast, it may easily be discerned, that Expression does not consist in the Staccato only, or in any one Power or Manner of playing. For Instance this Air,

Softly sweet in Lydian Measures, &c.

would be quite ruined by playing it Staccato; and again,

Revenge, Revenge, Timotheus cries, &c.

requires to be played in a very different Style from the foregoing Air.

Passions are to be expressed in Music, as well as in the other Sister Arts, Poetry and Painting.

Having thus explained what is meant by Expression in Music, we will return to the Point, viz. that the Organ and Harpsichord, though they have many other Advantages, yet want that great Excellence of Music, Expression. Surely it may not be thought a Straining of the Meaning of St. Paul's Words too far, when I surmise, that he, who had a fine Education, and in all Probability knew Music well, might have an Eye to the Want of Meaning or Expression of the ancient Cymbal, when he says, "Tho' I speak with the Tongues of Men and of Angels, and have not Charity, I am become as a sounding Brass, and a tinkling Cymbal." That is, though I have ever so much Skill in Languages, and the Arts and Sciences, my Knowledge is vain if I am without the Virtue of Charity, and my Works will have no Force, and will in that Respect resemble the Cymbal, which, though it makes a tinkling, and plays the Notes, yet is destitute of the main Article Expression. For we must not suppose, that so refined a Scholar as St. Paul was, could have such a settled Contempt for the Science of Music, as to make Use of it even as a Simile for what is trifling. We may venture to think, that the Apostle alluded to that Want of Power in the Cymbal to move the Passions, which other Instruments have.

This is the very Case with the modern Harpsichord; it is very pretty, notwithstanding it's Imperfections, with Regard to the Change of Keys, (of which more in it's Place.) But no one can say, that it speaks to his Passions like those Instruments which have so immediate a Connection with the Finger of the Performer, as to sound just in the Manner which he directs.

In that Case the Powers are great; you have the Numbers of Graces which have Names to them, and the still greater Number which have none; you have the Staccato and the Slur, the Swell and the Smotzato, and the Sostenuto, and a great Variety of other Embellishments, which are as necessary as Light and Shade in Painting.

To convince the Reader of this, let him hear any Master play Handel's Song, Pious Orgies, pious Airs, upon the Organ or Harpsichord, and he will find, that, though it will appear to be Harmony, yet it will want that Meaning, and (not to make Use of the Word too often) Expression, which it is intended to have given it by the Word Sostenuto, which Mr. Handel has placed at the Beginning of the Symphony.

Now a fine Performer upon the Violin or Hautboy, with a Bass to accompany him, will give it that Sostenuto, even with greater Strength than the human Voice itself, if possible.

I by no Means intend to debase that noble and solemn Instrument the Organ, nor the Wonders that are done upon it, nor the great Merit of the Performers who execute them, by what has been here said; only to discuss a little upon the Perfections and Imperfections of different Instruments, as the more the Imperfections of an Instrument are looked into, the more likely is the Ingenuity of Mechanics one Day or other to rectify them.

X

That every different Key in Music ought to have a different Effect or Sound.

This is an Error which belongs chiefly to those who play a little upon the Harpsichord; it arises from the Imperfection of their Instrument. As a greater Number of Keys would be inconvenient to the Performer, they are obliged to make one Note serve for another, such as B flat for A sharp, and many others, which necessarily renders some of the Keys imperfect. But we are not to take Notice of the Imperfection of any one Instrument, and regulate our Ear by that alone; we are to consider what is the real Scheme of Music, and what was the Intent of having different Keys introduced into Harmony.

It was intended for the Sake of Variety. When the Ear begins to be surfeited with too much of the Cantilenam eandem Canis, as Terence expresses it, then Contrivances are made, without infringing upon the Laws of Harmony, to have the Burthen of the Song upon a different Note; not that this Key is to differ from the former in it's Mensurations from one Note to another, unless it changes from a flat third Key to a sharp third, or vice versa. For notwithstanding all the different Sounds which an imperfect Instrument will give, in different Keys, there are in Reality but two Keys, viz. a flat third Key, and a sharp third Key; and however the different Keys upon any particular Instrument may sound, we will venture to affirm, that any Piece of Music, let it be set in what Key it will, either is not true Composition, or is performed badly, if it does not sound smooth and harmonious.

For though we do agree, that Variety is grateful in this Case as well as in others, yet that Variety ought to be introduced with as little Inconvenience as possible. When we shift our Scenes, we should order the Carpenters to make as little Noise in the Execution of it as they can help, and take Care that the Pullies are all well oiled. For shall any Man entertain me, by making a most hideous jarring Discord before he begins what he intends to be Harmony? It is as absurd as for a Lady to take you half a dozen Boxes on the Ear, before she permits you to salute her, and then to tell you she only did it, that you might have a more lively Apprehension of the exquisite Happiness which her unparallelled Charms should very soon make you sensible of.

We may apprehend the Difference of perfect and imperfect Instruments, by listening to a Harpsichord, when any Music, where the Key changes often, is played, and to a fine Band, such as the Playhouse or the Opera. We shall find, in the latter, that the Composer has taken Care to make every Transition quite smooth and harmonious; and that tho' the Music be ever so cromatic, yet it never departs from it's melodious Effect. Whereas in an Organ or Harpsichord, even the greatest Performers cannot avoid a disagreeable Roughness in complicated Harmony. Nevertheless, as has been before observed, we must acknowledge the Organ to have Powers which other Instruments have not.

XI

That a Piece of Music which has Flats set before it, is in a Flat Key on that Account, and vice versa with Sharps.

This is so well known to be an Error, by all those who have arrived at any Proficiency in Music, that very little need be said about it; however, it is a very common Error.

A Key is not constituted flat or sharp, by having Flats or Sharps at the Beginning of the Piece of Music; but it depends upon the third Note upwards from that Note in which the Music is composed. For Instance, if the Piece is composed in D, and we find that F is natural, or only half a Note from E, then it is in a flat, or flat third, Key; if F is sharp, or a whole Note above E, then the Piece of Music is composed in a sharp third Key. But as there are so many Books extant about Thorough Bass, which give a full Account of this, it will be needless to say any more about it, only to mention it as an Error, among other Errors. The Reader shall not be tired any more with Music at present, but for Variety we will shift the Scene a little while.

XII

That apparitions or Spectres do exist; or that the Ghosts of Men do appear at, before, or after their Deaths.

We would not be thought, in the following Discourse, to call in Question that great Miracle of our Saviour's rising again the third Day, and appearing to the Twelve: What shall be here said, will rather prove the Miracle to be the greater, and therefore more worthy the interfering Hand of Omnipotence.

But we must not suppose that the Supreme Being will condescend to pervert the Order of Nature for Individuals. The ancient Heathens had a true Notion of the Greatness of him, qui Templa Cœli summa sonitu concutit. Ter. Eun. And Horace observes,

Nec Deus intersit, nisi dignus vindice nodus.Art. Poet.Since it must be no less than a Miracle which causes an Apparition, I shall proceed, without any Scruple, to prove that there is no such Thing in Nature really existing.