полная версия

полная версияA Short History of English Music

His tastes were, it must be said, so far as appertaining to art, of a peculiarly low order.

Ben Jonson, who supplied the literary part of the most famous of these plays, was, for a man of his genius and learning, extraordinarily coarse in his language even for those days, and his comedy, "Bartholomew Fair," which was about the worst in this respect that even he perpetrated, was King James' special favourite.

Of music the King knew little and cared less, and it had come, probably in consequence, to play a secondary or even lower part in the productions of this time. In proportion as they increased in splendour they lost in artistic value, and, similarly as they came to be the exclusive amusement of the wealthy, so they lost their hold on the people.

In the year 1616 the splendour and extravagance of these displays culminated in the representation of the masque entitled, "The Golden Age Restored." It was played by the ladies and gentlemen of the Court. George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, so pleasing his Majesty that the latter cried out in ecstasy, "By my soul, mon, thou hast done it full weel." The King is said to have contributed £1000 on the occasion. There is little need for obvious comment on this fact.

It is worthy of remark that for some years before this, most of the performances of which there is any record were given at Whitehall, or in such buildings as the Inns of Court. They had grown out of the simplicity characterising primitive popular spectacles, and had become rather a medium for the idle pastimes of the rich.

The high tide of joyousness and gaiety in the life of the people had been reached in the reign of Queen Elizabeth, and was fast receding. The spirit of the Reformation was getting hold of them and, perhaps, in its most fanatical aspect.

However, the masque had served its purpose. It had been in earlier days a source of harmless vent to the exuberant spirit of the people, and it was later to become the source of inspiration from which the primitive opera, as represented by Purcell's "Dido and Æneas," drew breath.

Of secular music, demanding more skill in invention and more proficiency in performance than the ballad, were the madrigal, catch, round, glee, and similar forms of expression. Being concerted pieces demanding the simultaneous singing of various parts, a technical training was, of course, necessary to enable one to join in them.

Their great popularity in all classes of society is sufficient proof, however, of the general training in the art that then existed. In fact, it was considered an essential thing in a gentleman's education, and the ability to take part in a "catch" or "round" was as natural to him in those days as it is to shoot or play cricket in these.

We cannot give the reader a better means to realise this than by quoting Shakespeare again, in whose words every feature in that wonderful age is held up to the mirror.

In "Twelfth Night" the following will be found: —

Sir Toby: Shall we rouse the night-owl in a catch, that will draw three souls out of one weaver12? Shall we do that?

"Sir Andrew: An you love me, let's do it: I am a dog at a catch.

"Clown: By'r lady, sir, and some dogs will catch well.

"Sir Andrew: Most certain: let our catch be 'Thou knave.'

"Clown: 'Hold thy peace, thou knave,' knight? I shall be constrained in't to call thee knave, knight.

"Sir Andrew: 'Tis not the first time I have constrain'd one to call me knave. Begin, fool; it begins, 'Hold thy peace.'

"Clown: I shall never begin, if I hold my peace.

"Sir Andrew: Good i' faith! Come, begin." (They sing a catch.)

The "catch" was a melody started by one singer and followed by another at an interval of one or more bars, singing identical notes, who would be succeeded by yet another in a similar manner. It depended upon the dexterity with which the performers would catch up their notes at the right moment as to whether harmony or chaos resulted.

It was a popular form of amusement, but we are hardly surprised when Malvolio appears on the scene and addresses the singers thus: —

"My masters, are you mad? or what are you? Have you no wit, manners, nor honesty, but to gabble like tinkers at this time of night? Do you make an ale-house of my lady's house, that ye squeak out your cozier's catches without any mitigation or remorse of voice? Is there no respect of place, persons, nor time in you?"

To all of which Sir Toby, treating it as an aspersion on his skill in music, replies, "We did keep time, sir, in our catches."

The madrigal was an altogether more serious form of art, and, except for the words, might be identified with the best specimens of ecclesiastical music. It was polyphonic in treatment, and generally grave in character. Indeed, to judge by some of the most celebrated examples, it seems almost savouring of jest to describe it as secular.

Of English composers, perhaps those who most excelled in this class of composition were Byrd, Dowland, and Orlando Gibbons. The most splendid example being that entitled, "The Silver Swan," by the last-named.

The glee, although less serious in character, as its name implies, was a truly artistic type of concerted music, and there are numerous specimens of early date of great beauty and contrapuntal skill, but they are characterised by comparative simplicity.

The transition from one to the other would seem natural, seeing the extreme elaboration that rendered the madrigal difficult of interpretation to any but highly-skilled singers.

The beautiful "Since First I Saw your Face," by Thomas Ford, can hardly be described by either title, for while it is removed in tone from the glee it lacks the atmosphere of the schools that the madrigal suggests. The glee, as it is popularly known to-day, is of a later date, and came to perfection about the middle of the eighteenth century.

It is a remarkable fact that perhaps the most beautiful and certainly one of the most skilfully written specimens of mediæval music, is also one of the most ancient. The date of it must be purely conjectural, although the scholar may to some extent be guided by the words as to the actual century of its origin.

The opening words, "Sumer is icumen in," are probably familiar to most readers, since they are ever in evidence when the question of old English music is under consideration. Indeed, it would take many volumes to record what has been written about this extraordinary composition.

From whatever point of view it is judged it commands admiration and wonder.

It demonstrates that in the art of music England was then not only abreast of foreign nations, but probably in advance of them.

It shows that polyphonic writing must have reached to a high point of development even so far back as the thirteenth century, and there is every reason to believe, even long before then.

It seems to me to be only a very obvious deduction. Just as there must have been many great poets before Homer, so this work must be the fortunate survivor of a long-lost school that, unhappily for us, had no enduring medium for transmission of its genius to later ages.

It exhibits, apart from the skill that characterised ancient ecclesiastical music, from which it indubitably sprang, a rare genius in interpreting the spirit and feeling of the words. In this respect it may be said to have anticipated centuries to come. With every appreciation, sincere and even reverend, of the ancient music of the Church, it must be acknowledged that in spirit it was rigid, severe and formal. In other words, it appealed to the religious and intellectual sense rather than that of beauty. "Sumer is icumen in," on the contrary, seems to be the work of one who is able to leap over the centuries and speak in the tones of ages unborn, to be, in fact, a forerunner, a teacher of the ages then in the womb of Time.

It has, in perfection, three great qualities of the highest art – perfect skill in execution, commanding appeal to the purest emotions, and the power to leave the mind in a state of ecstatic rest or emotional contentment that makes one oblivious of the world while listening or watching. It was the outcome of an age of great religious enthusiasm. The monks had great dreams, and with them came the energy that inspired their brains to the utmost fulfilment.

The dream that led to the Crusades is the one that has most appealed to the imagination of the world; but it was only one of many.

"Sumer is icumen in" was written in a form that seems to have especially appealed to those early composers, for the canon13 was a constant medium of musical expression in mediæval times.

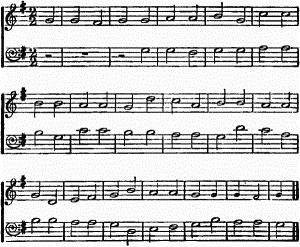

That the reader may the more readily understand, I quote here a specimen that is at once beautiful and familiar to all, and is known as the "Morning Hymn." Its simplicity will make it intelligible to the least technically instructed of musical readers: —

It will be observed that the last four notes in the treble clef indicate the repetition of the melody, which can continue indefinitely as here represented.

When we come to the consideration of instrumental music of olden times, we have little to guide us in the formation of any dear conception of its value or importance.

It is evident, however, that up to the time of Purcell or that immediately preceding it, the state of development was altogether inferior to that of vocal music.

For many centuries, except as regards its use in the Church, it occupied the humble position of handmaiden to the sister art of dancing.

Such of it as still exists is, practically, all written in dance measure. The dances were, it is true, in varied forms and rhythms. Some were stately and even serious in character, and offered the composer an opportunity to display his skill in a more thankful task than in furnishing accompaniments to the lighter and more frivolous ones.

Beautiful specimens of these are found in the compositions of William Byrd, John Ball, Orlando Gibbons, and others of the same period; they were mostly written for the virginals.

To those living in this age of stupendous achievement in the art, the comparative simplicity and ineffectiveness of instrumentation may well seem strange, seeing to what a point of splendour vocal music had attained.

The explanation is, I think, to be found in the defective nature of the instrument on which the composer had to rely to provide the sounds that his consciousness urged him to produce.

The violin had yet to be brought to perfection through the genius of a Stradivarius, and time was needed to show its full capacities in the hands of a Paganini.

The wind instruments, too, of the modern orchestra are of incomparable possibilities to those in use in the sixteenth century.

However, with the improvement and perfecting in their manufacture came a decided step towards a higher and independent form of art, and that this advance was not slowly taken advantage of is shown in the most extraordinary way in the works of Purcell.

Again, the very imperfect forms of musical notation must have always proved a stumbling-block to those early musicians. Even to-day, with its advanced methods, the act of putting on paper a modern orchestral composition is a work of enormous labour. The reader will understand this, when I say that music which takes but merely a few minutes in performance may easily take the composer as many hours to translate on to the pages of his score.

That this obstacle to musical progress was signally true as applied to organ music, I am convinced.

An organ is known to have been used in a French cathedral as early as the sixth century.

Primitive in its structure as it must have been, it probably had sufficient pipes to aid the congregation in the singing of the plain-song.

As time advanced, the monks, ever restless in their desire to add glory to the Church, made unceasing efforts to improve this great adjunct to her service, and by the fifteenth century an instrument had been constructed that was secure in the promise of untold possibilities, and had already become a verification of their early dreams.

The sixteenth century saw the organ come into general use, and in the early days of the seventeenth it arrived at maturity. The immense advance in the structural appliances in modern times are, it would seem, simply scientific application to ancient ideas.

One cannot help thinking how many must have been the inspired strains that rang through cathedral aisles in those early days as the hands of the monks wandered over the organ keys, the double incentives of religious fervour and love of art urging them on to higher achievement: a strange and yet fascinating figure of saint and artist.

By the time of Purcell instrumental music had advanced beyond the dance measure, and arrived at a state of independence. It could stand by itself without the aid of singer or dancer to sustain it. The process of emerging from the parasitic stage of clinging to these arts for sustenance was completed, and it had struck its roots so deep down that future ages might well, with wondering amazement at its magnificent growth, find it difficult to grasp the idea of its humble origin. The compositions left, in this kind, by Purcell, such as the fantasias, sonatas, incidental music to plays, harpsichord and organ music, indicate only, it is true, the first offshoots of the wonderful tree that was destined to so fascinate the world, but they gave birth to many noble branches that helped to invigorate the initial life in its struggles for existence, and were the most prolific of the tendrils that make for healthy growth.

In conjunction with his sacred music, these amply justify the claim made for Purcell that he was, from whatever point of view he may be judged, the greatest of all English composers.

CHAPTER III

EARLY ENGLISH COMPOSERS

THOMAS TALLIS (OR TALLYS)Most of the pre-Reformation music destroyed – Tallis, the oldest English musician of which anything certain is known – Organist of Waltham Abbey at time of the suppression of the monasteries – Date of his birth unknown – Favourite of King Henry VIII. and Queen Elizabeth – State of difficulty and danger in intervening reigns – Chaotic state of things in the Church – Queen Elizabeth's policy – View of it taken by the present Dean of St. Paul's Cathedral – Greatness of Tallis as a composer – His death.

We are, unfortunately, not able to write of the earliest English composers, as much of their work (and with their work their very names) perished at the time of the destruction of the monasteries by King Henry VIII. in 1540, and what was left of it was destroyed by fire during the sacking of the cathedrals by the Puritans in the Commonwealth period. We are, then, obliged to begin with the early English composers, who date no further back than the sixteenth century and the Reformation.

In dealing with these and their music, it is impossible to think without emotion of the terrible sacrifice of treasures of art caused by the veritable holocaust made of them by the Puritans, for, of the work of centuries, there is, practically, little or no trace left. What we do know of the works of those composers who lived before and during the early Reformation period, shews that ecclesiastical music had arrived at a point of great splendour, and if Tallis may be considered as the descendant of a great school of composers, which he undoubtedly was, it can help us to realize the extent of our loss.

He was, fortunately, able to protect his own work, or, doubtless, that would have perished with the rest, since all of his early music (and some of the noblest specimens) was written for the monastery at Waltham Abbey.

Tallis stands out pre-eminent among the early Church composers, and, indeed, has been generally called the father of English music. The date of his birth is not known, but as he was organist and composer to an important monastery at the time of its dissolution in 1540, it is not only evident that he must have been born early in the century, but that his genius was decidedly precocious. Some authorities give the date as about 1529; Grove's Dictionary, on the other hand, as supposedly in the second decade of the century: this seems more probable, as the former would have found him holding such a conspicuous appointment at the age of eleven. It is a fact of much significance that he was a prominent composer before the Reformation, and thus a descendant of the ancient school of English Church music, pure and unalloyed.

His earliest compositions were, of course, written to Latin words, and the publication of his motets in that language in 1575, more than thirty years after its suppression, suggests that the call of his early training and associations was greater than he could resist, for it must be borne in mind that those were days of fierce bigotry, and many had been undone for acts much less provocative of "suspicion."

Indeed, of all the immediate changes in the Church services effected under Henry VIII., perhaps the most important, after those asserting severance from Rome, was the substitution of English in place of Latin in their administration, and on no point were the reformers more jealous, since it implied complete freedom from outside interference and, above all, that of the Pope.

That Tallis escaped trouble on this occasion shews that he was a decidedly fortunate, or as some unkind critics suggest, a decidedly adroit being. They even go to the length of comparing him to the "Vicar of Bray," because of the continuity of his employment in the Church during four reigns, in which such diverging views were inculcated and, outwardly at least, demanded of acceptance. Thus Henry VIII., who broke the Roman connection, but generally upheld its doctrines; Edward VI., who repudiated them; Mary, who not only enforced them, but restored, as far as she was able, the status quo before the act of separation from Rome; and Elizabeth, who reverted, practically, to the position as it was at the death of her father, additional alterations in the liturgy excepted.

The "Vicar of Bray" theory seems to me to be quite easy of demolition. With regard to King Henry and Queen Elizabeth, they were, both, skilled musicians and perfectly capable to appreciate the genius of Tallis in its highest aspects, and were, therefore, little likely to rid the Church of so brilliant an ornament.

In the intervening reigns, it seems only natural to suppose that many who still adhered to their Catholic principles, while bowing to the inevitable for the time being, and, knowing the precarious state of the health of the young Prince, foresaw the probable accession of Queen Mary and the consequent restoration of the ancient Church. Of these, Tallis may have been one.

On the actual accession their hopes seemed justified to the fullest extent, and only the fact of the Queen proving childless rendered them futile.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to say with any approach to exactitude what were, precisely, the immediate changes in the forms of the Church services insisted on at the moment of King Henry's rebellion against Papal supremacy. It is, however, only natural to assume that all reference to that supremacy would be eliminated, and that the use of the English language would be insisted upon, so as to mark, once and for all time, the absolutely irrevocable nature of the act.

The state of affairs in the Church must have been absolutely chaotic, what with those who, while remaining Catholic in principle, were willing to accept such changes as were not inconsistent with their faith, and others who were anti-Catholic by conviction and desirous of banishing all traces of the past, so far as it might be possible.

It was to these that the young King extended his sympathy and help, on his accession to the throne.

His death after a short reign and the consequent accession of Queen Mary, simply made "confusion worse confounded." Although strenuous in her methods, she had not time to achieve what she had at heart, and her death put an end for ever to the hopes of the extreme Catholic party. However much had been carried out that Queen Elizabeth at once settled herself to undo, and thus prolonged, perhaps inevitably, the crisis through which the Church was passing.

It is not difficult to imagine the delicate position in which musicians found themselves at various times during this crucial period. Let me quote Mr. Myles B. Foster in his interesting book, "Anthems and Anthem Composers"14: "Can we not picture the puzzled state of these poor composers, never knowing whether, by setting their music to the new English words, they would be burned alive, or, by using the old Latin ones, they would be hanged!"

With the accession of Queen Elizabeth these critical times may be said to have become a thing of the past – at least for the musician. The policy of the wonderful Queen was based on compromise, by which she endeavoured to so broaden the lines of the Church as to make it possible for the two factions to remain within its boundaries. So far as the extremists on either side are concerned, the idea was doomed to failure, but while she lived she pursued the policy with characteristic pertinacity, and unenviable was the fate of the too-reforming Bishop who encountered her displeasure. The state of the Church of England to-day seems, at once, a tribute to her genius and foresight, for while the trend of feeling and opinion certainly continued to move in the direction of Protestantism, the opposing principles never became quite extinct.15

It was, undoubtedly, under circumstances of great uncertainty that Tallis was called upon to write music for a reformed liturgy that was at once novel and, probably, seeing his early training, distasteful to him. How he met the emergency is evident to-day, for his "Preces and Responses" not only remain in use, but are a priceless possession of the English Church. On the greatness of Tallis as a composer it is needless to insist, for it has been universally acknowledged. His contrapuntal skill was amazing, his fertility and originality equally so, and everything he wrote bears the impress of a nobility of mind difficult of description. That he remained in high favour with the Queen until his death, is shewn by the grants of land and other proofs of her regard that she bestowed on him. A complete list of his compositions (so far as can be known) is given in Grove's "Dictionary of Music and Musicians," and is a striking proof of his immense activity.

To secular music he seems to have been quite indifferent, for, to all appearances, he wrote little or none.

He died in 1585 when, probably, about seventy years of age, and was buried in the parish church of Greenwich. We have other of the early English musicians to deal with, but none, I think, of such unique interest, as he was the first of whom we have any reliable record, the works of his predecessors having been literally burnt out of existence.

WILLIAM BYRDDate of Byrd's birth unknown – Pupil of Tallis – Strict Catholic, yet employed in the English Church – Explanation – Queen Elizabeth's protection – Organist of Lincoln Cathedral – Member of the Chapel Royal – Granted sole privilege of publishing music in conjunction with Tallis – Greatness as composer, both sacred and secular music – His masses – His character – His death.

The date of the birth of this composer is quite unknown. Many speculations have been made on the subject, but they are purely conjectural. It seems certain, however, that he was born late in the first half of the sixteenth century, and thus at the time of the highest development of the ancient English ecclesiastical school of music. He had the inestimable privilege of being a pupil of Tallis, and remained his friend and colleague until the death of the latter dissolved the connection in 1585.

Unlike most of his contemporaries, he sturdily refused to change his religious views at the capricious behests of any monarch, and, strange to say, he does not seem to have suffered for his constancy materially, for he continued in official employment and the favour of Elizabeth as long as the Queen lived.

This fact has often evoked expression of astonishment, and has been cited as a proof, not only of the unstable position in the Church itself, but of instability in the character of its rulers.