полная версия

полная версияA Short History of English Music

To whatever cause it may be assigned, it has to be admitted that musicians in those days had a most unenviable reputation, and were looked upon with the greatest contempt.

One qualification of this statement may be made, as there is little doubt that a great distinction was made between the composer and the "musician."

Every rogue and vagabond who scoured the country giving crude and generally offensive performances styled himself musician, so the public, having no greater genius for fine discrimination then than now, came to regard all persons who were engaged in the performance of music, if not with active aversion, at any rate with passive contempt.

It is in these early times that the foundation of the feeling was laid, only to be strengthened later on when Puritanism came with fanatic intensity to still further deepen it. How engrained in the spirit of the people this sentiment became is evident, even to this day.

That the composer of music was regarded in a different light, we shall be able to prove.

He obtained degrees at the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge, where he proceeded to the high position of Professor of the University in the Chair of Music.

Leases of Crown lands were made to him, with grants of armorial bearings in some cases; indeed, there are evidences of many kinds to show that his calling was held in high esteem. With the "musicians," as they were called, or "minstrels," as they called themselves, things went from bad to worse. Doubtless reinforced again by cast-off camp-followers from the armies of the Wars of the Roses, they became, by the reign of Queen Elizabeth, not only a source of terror to the countryside, but a nuisance and a pest to the towns. Gosson writes, about 1580: "London is so full of unprofitable pipers and fiddlers that a man can no sooner enter a tavern, than two or three cast of them hang at his heels, to give him a dance before he depart."5

In 1597 a law was passed in which they were classed as "rogues, vagabonds, and sturdy beggars," and were threatened with severe penalties.

The War of the Rebellion probably brought them still another accession to their ranks, as, so far from being harmed by this threat, things must have got even worse, to judge by the following edict issued by Cromwell only a few years later: —

"Any persons commonly called fidlers or minstrels who shall at any time be taken playing, fidling, and making music in any inn, ale-house, or tavern, or shall be taken proffering themselves, or desiring, or intreating any to hear them play or make music in any of the places aforesaid, shall be adjudged and declared to be rogues, vagabonds, and sturdy beggars."

It may be at once assumed that if they were able to evade the hands of Elizabeth, they were little likely to escape those of Cromwell, who may be said to have, at last, cleared the country of what had become a positive menace to the security of life, since under the guise of wandering minstrels, highwaymen and other criminals had long been wont to carry on their occupations with comparative immunity.

The age of Queen Elizabeth was one of transition, the Commonwealth marked the birth of the new era, and with it the final disappearance of the picturesque, even if somewhat depraved, English troubadour.

CHAPTER II

MUSIC BEFORE AND DURING THE REFORMATION – (continued)

Secular music dating from the thirteenth century – Origin lost in antiquity – Earliest specimens, dance music – Morris dance traced to Saxon times – Dancing always associated with singing – Gradual independence – Popularity of the month of May – The ballad and its antiquity – Popular specimens – "Parthenia," a collection of pieces for virginals – Life in England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth – Its happiness – Authority of Professor Thorold Rogers – Great men living at the time – Pageantry and the Queen – Her love of dancing and music – Her sympathy with the joys of her people – Queen Elizabeth as a musician – Sir James Melvil and his adventure – The masque – Its origin – Popularity – James I. and art – Masque forerunner of opera – The madrigal, catch, round and glee – Shakespeare and the catch – "Sumer is icumen in," a wonderful specimen of ancient skill and genius – The "canon" – Instrumental music – Explanation of its late development – Purcell – Conclusion.

Authentic examples of secular music in England date from the thirteenth century. It is not from this fact, though, one must suppose that it did not exist prior to that period. On the contrary, music of some kind or other has, doubtless, been a source of solace as well as amusement for untold years.

For antiquity, vocal music stands pre-eminent. Ages must have passed before instrumental music came to any position of efficacy at all correlative with it.

It must be remembered that music as we know it, is the gift that the ancient Church gave us centuries ago, and that the pangs of its birth were suffered in days of which all sense of record is lost.

That there were seculars, even in those remote days, whose ideas of musical progress would not be bound by the ties of ecclesiastical gravity may be taken for granted, and as the art progressed in the Church they would naturally take advantage of it to further their skill in the direction of a lighter and less serious type.

To seek for the earliest examples of dance music is simply to grope in the dark. As to its progress, all that can be suggested is that it fairly synchronises with that of sacred character.

This need be no matter for surprise, since seeing that the Church never did other than encourage the healthy outdoor life of the people, it may be assumed that the monks, who were responsible for the music in the Church, were as willing as able, to help in the advancement outside of it.

Research makes it certain that the first efforts at dancing were accompanied by singing, and only in its latest stages of advancement was it strong enough to dispense with this, and rely on the attraction of the rhythmic movements of the dancer.

From this it will be reasonably inferred that for countless centuries the two arts remained in combination, before the incentive genius of either proved too strong to longer brook the artificial ties that had bound them together.

It is said that the Morris dance can be traced to Saxon times, and that it is the one that has remained with the least variation from its original form. It must be admitted, however, that the difficulty of absolutely proving these assertions is almost insuperable, notwithstanding the amount of research that has been directed to the subject.

It can be traced definitely as far back as the reign of Edward III., and in its most popular form, is known as the may-pole dance.

It was particularly associated with May Day, and was danced round a may-pole to a lively and capering step.

Reminiscences of these old "round" dances may be traced in games played by children to-day, such as "Kiss in the ring," "Hunt the slipper," "Here we go round the mulberry bush," and others of a similar type.

The onlookers sang and marked the rhythm by the clapping of hands.

With increasing skill in the making of musical instruments, and increasing art in playing on them, the dance gradually became independent, as is manifestly shown by music that is still extant, and while being evidently intended for dancing, is quite unsingable. Once then separated, the art naturally developed on bolder and more original lines. As the human voice was the first medium of expression in music, all lines necessarily radiated from it. Singing induced dancing; dancing required a more certain rhythmic force than the voice could supply; hence artificial aid by means of instruments, the first, doubtless, being those of percussion.

With the arrival of instruments of a more advanced character and capable of more varied expression, the progress of the art would naturally proceed with greater rapidity, and on lines displaying greater variety.

England, in those days, was avid of pleasure. It is little to be wondered at.

We speak of the people, not of the nobles, whose wealth enabled them to combat the ordinary existing conditions.

Their day depended, in a very special sense, on the sun, in a manner surprising to those of us living in the twentieth century. It began with the rising, and ended with the setting.

Artificial light, except of the most primitive description, was a luxury entirely out of their reach.

If we, in modern times, remembering its fickle climate, wonder at the popularity of the month of May, and the adulation it received at the hands of the early poets, a little consideration will soon supply the cause. The long, weary months of winter, with its darkness and cold, had been endured; the bitter winds of March and April were over, and the long days and tempered breezes came to the people with a relief, the intensity of which is difficult to realise, with all the means of comfort that modern civilisation has placed at our disposal.

The ballad, as distinguished from the song, is peculiarly typical of the Northern races, and was, up to the time of Queen Elizabeth, a favourite feature of English music. As its name implies,6 it was danced as well as sang; later on the dance was dispensed with.

Its antiquity is unquestionable, but it is, as is so often the case, impossible to assign any definite date to it.

The early part of the eleventh century certainly knew it in England, as the following stanza proves.7 It tells of a visit paid to the city by King Canute: —

"Mery sungen the muneches binnen Ely.Tha Cnut ching reu therby:Roweth, cnites, noer the land,An here we thes muneches saeng."This may be translated for the modern reader as follows: —

"Merry sang the monks of Ely,As King Canute rowed by.Row knights, near the landAnd hear we these monks sing."The music is, unfortunately, lost.

In Roman times a popular feature of the processions organised in honour of some newly-arrived conquering soldier was a band of dancers who, while gyrating in graceful movement, sang poems, reciting his heroic deeds.

The praise of heroes was, from the earliest, the dominant feature of the ballad, and, although far removed, as it must be from anything resembling even mediæval methods, the Greek and Roman form of it is most probably the real source from which it is derived.

There are many kinds of ballad known to England, but they are narrative, as a rule, such as "Chevy Chase," and many others of a similar style. Some are sad, some are gay; none are sentimental. One that can be seen in the Sloane Collection in the British Museum, "Joly Yankyn," is probably not much later than the one previously quoted. The name will recall Friar Tuck to the readers of Scott's "Ivanhoe."

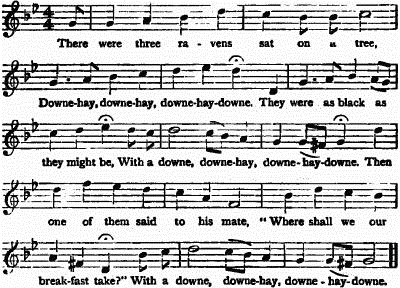

A ballad that is believed to be of Eastern origin is the following: —

"There were three ravens sat on a tree."

We are on safer ground, however, when we come to such a one as "To-morrow the Fox will come to Town," with the refrain, "I must desire you neighbours all, to hallo the fox out of the hall." This is altogether more English in character, and is filled with the spirit of open air life.

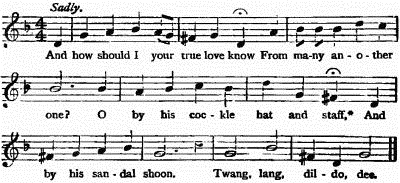

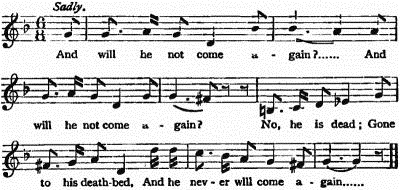

Other examples that seem inevitable of quotation, are those that Shakespeare has made immortal, by putting them into the mouth of Ophelia, in the tragic scene from Hamlet.

The music that we quote here is that which, there is every reason to believe, was sung at the original production.

The style accords with Shakespeare's time.

Unfortunately when Drury Lane Theatre was burnt down in 1812, the music library was destroyed. Happily, however, Mrs. Jordan, the celebrated actress with whose fame the part of Ophelia is for ever associated, was alive, and was able to sing to Dr. Arnold, a famous musician of the time, the melodies, as they had been rendered in the theatre in her time, and probably for centuries past.

"How should I your true love know?"

In "Parthenia," a collection of pieces for the virginals (an instrument that may be described as the ancestor of the piano), which was published in 1611, it is shewn to what a high point of development the composition of dance music had arrived.

The music was composed by the three most celebrated English musicians then living, William Byrd, John Bull, and Orlando Gibbons – Tallis had been dead over twenty years.

The pieces are of the most stately kind, in general, and would scarcely realise the modern conception of dance music, but they are beautiful specimens of the art of those days, and cannot but command our admiration.

Of the more lively and frivolous dances the one known as Trenchmore was the most popular.

"Be we young or old … we must dance Trenchmore over table, chairs and stools."10

Selden, in his "Table Talk," "Then all the company dances, lord and groom, lady and kitchen maid, no distinction."

The more one comes to learn of life in the England of those days, the more one becomes convinced that, taken as a whole, life was both happy and joyous. No less an authority than Professor Thorold Rogers, after profound research into the social conditions of the Middle Ages, says they show that a state of happiness and content prevailed.11

Dancing was advised, too, as "a goodly regimen against the fever pestilence."

The fact that there is comparatively little of old-time music extant is due to the late invention of music printing and the slow progress of musical notation. "Parthenia" was, as the title page tells, the first music for the virginals ever printed, and yet appeared as late as 1611.

From that time, naturally, records of everything written of any importance, exist.

In the reign of Queen Elizabeth the typical life of the England of old, is shown at its best, and in its most characteristic state of development.

Soon afterwards, foreign influence, aided by a foreign Court, added to the depressing element of Puritanism, was to shake to its foundations this character and to mould it into that type which for centuries it retained.

The Wars of the Roses had long been over, and economic conditions greatly modified and improved. The genius of the people seemed to burst out as if relieved from intolerable repression.

The absence of the unceasing scares and horrors of war gave them the opportunity that had so long been denied.

To think that such men as Shakespeare, Bacon, Burleigh, Drake, Raleigh, Tallis, Byrd, and Orlando Gibbons were living at the same time, and may have often passed each other in the streets of London!

There can be little doubt that the reign of Queen Elizabeth was the happiest the people had ever experienced, and it may be truly said that the Queen was the very incarnation of the spirit of the age.

Her love of pageantry and display was an unfailing source of joy to them, all the more, since they were frequently called upon to assist at many of the great functions that were organised in her honour by the great nobles. Her frequent progresses through the country were occasions, not only of gratification to herself, but excitement to them, relieving as they did the monotony of toil and the sense of isolation incidental to country communities in those days of difficult communications. The Reformation had not been sufficiently long in progress to affect the spirit of the people. It had not really reached them. If England ever deserved the appellation of "merrie," those were the days.

The sports were, if rough and coarse, joyous and frank.

To the Englishman of to-day their amusements may seem childish enough, but education was then, it must be remembered, entirely confined to the few, and the amenities of life, such as we know, were practically absent. A favourite feature was a procession of musicians and dancers dressed to represent such popular characters as Robin Hood and Friar Tuck, and bedecked with bells on elbow and knee that jingled as they danced.

The badinage that passed between the performers and onlookers was of a kind, it must be confessed, that would fall strangely on the ear at the present day, but still, there is every evidence that although the manners were rough and the language guileless of restraint, the heart of the people was sound at the core, and the deep-seated sense of religion in the Anglo-Saxon race was as present then as at any time in its history. The exuberant spirit is ever evidenced by the wealth of drinking songs. These seem to have been as much in vogue in those days as the monotonous frequency of love songs, from which we suffer, is in these.

Shakespeare makes good-humoured fun of the propensity in "Twelfth Night: or What you Will." In the famous drinking scene between Sir Toby Belch and Sir Andrew Aguecheek he satirises their foibles, it is true, but in the most delightful and even sympathetic manner, and certainly gives Sir Toby a telling rejoinder to the upbraiding of the sober-minded Malvolio, who had come with the intention of putting an end to the carousal: "Dost thou think that because thou art virtuous, there shall be no more cakes and ale?"

Music was everywhere apparent. Wherever the monarch went, it was made a special feature at all functions. Whatever entertainments were devised by her courtiers, it ever had a principal place. Of the most gorgeous and notorious of them, the one given by the Earl of Leicester in her honour at Kenilworth Castle takes the first rank. Bishop Creighton, in his "Life of Queen Elizabeth," gives so vivid a description of it that, as one reads, the imagination seems, as it were, to become vitalised.

The Queen especially enjoyed these pageants, as they seemed to symbolise at once the greatness of her position and her personal dignity.

Those who entertained her, well knew both her haughty Tudor temper and intense femininity. To evade the one and satisfy the cravings of the other was the end ever held in view.

Hence, all kinds of contrivances were devised to glorify her person in allegory. In one, Triton is represented as rising from the water and imploring her to deliver an enchanted lady from the wiles of a cruel knight; upon which the lady straightway appears accompanied by a band of nymphs, Proteus following, riding on a dolphin. Suddenly, from the heart of the dolphin springs a choir of ocean gods, who sing the praises of the beautiful and all-powerful Queen!

Now Elizabeth was neither beautiful in person or character, but she possessed the very genius of sovereignty.

The imperious Tudor temper to which she constantly yielded, certainly detracted from her womanly qualities, but what she lacked as woman, it is only just to say, she more than made up for as Queen.

On this occasion, besides the great pageant, rustic sports of every kind, including bull baiting, were indulged in, and "a play was acted by the men of Coventry."

That she shared her people's love of dancing is again shewn by the following: "We are in frolic here at Court," writes Lord Worcester in 1602, "much dancing of country dances in the Privy Chamber before the Queen's Majesty, who is exceedingly pleased therewith."

In fact, her sympathy with the amusements of the people, and her encouragement of every healthy enjoyment, are certainly great factors in the hold her memory has retained in the minds of the English race.

There are other reasons, of course, of graver import, but they do not enter into our immediate consideration.

All the Tudor monarchs were essentially musical, as being Welsh they well might be. Henry VIII. was a composer of both sacred and secular music. I well remember that the first of an old volume of anthems in the library of Salisbury Cathedral was by no less a personage than that monarch himself. It was not, however, so far as my experience went, ever sung.

Queen Elizabeth was also an accomplished musician and an expert performer on the virginals, as the following quotation goes to prove. Its interest is peculiarly striking as it shows yet another side of the character of this many-sided, wonderful woman. It is from the memoirs of Sir James Melvil, at the time Scottish Ambassador: —

"The same day after dinner, my Lord of Hunsden drew me up to a quiet gallery that I might hear some music (but he said he durst not avow it), where I might hear the Queen play upon the virginals. After I had harkened awhile I took by the tapestry that hung by the door of the chamber, and seeing her back was toward the door, I entered within the chamber and stood a pretty space, hearing her play excellently well; but she left off immediately so soon as she turned her about and saw me. She appeared to be surprised to see me, and came forward, seeming to strike me with her hand, alleging she was not used to play before men, but when she was solitary, to shun melancholy. She asked me how I came there? I answered, as I was walking with my Lord Hunsden, as we passed by the chamber door, I heard such a melody as ravished me, whereby I was drawn in ere I knew how; excusing my fault of homeliness as being brought up in the Court of France, where such freedom was allowed; declaring myself willing to endure what kind of punishment her Majesty should be pleased to inflict upon me for so great offence. Then she sate down low upon a cushion, and I upon my knees by her; but with her own hand she gave me a cushion to lay under my knee; which at first I refused, but she compelled me to take it. She enquired whether my Queen or she played best. In that I found myself obliged to give her the praise."

Perhaps the most important form of musical and dramatic art that came into prominence during the Tudor period was the masque.

It was a combination of the various arts of music, acting, dancing and mimicry. Simple and unpretentious in its primitive form, it became subsequently, an entertainment of the most elaborate and gorgeous kind, and one that was conspicuously encouraged and patronised by Royalty. It attained to the highest pitch of artistic splendour and efficiency in the reign of James I.

From nearly every point of view it may be reasonably described as the forerunner of modern opera.

Its origin, like all that has to do with music in England, is obscure and dates back to centuries of which we have little or no record. In all probability it was the outcome of the early performances encouraged by the Church, of representations of biblical subjects, to which we refer in another chapter.

By the time of Henry VIII. it had become as popular a feature in the life of the people as cricket or football is to-day.

Not only did the simple people take part in the performances, but the principal characters were frequently performed by members of the nobility and of the Court, Royalty itself not having altogether resisted their fascination.

The explanation of the vogue to which they attained in the reign of James I. is probably that the monarch was much less in touch generally with art, and particularly that akin to the Shakespearean drama, than was his more enlightened and intellectual predecessor. In fact, the drama proper was altogether beyond his region of intelligence, and since the masque, while making sufficient appeal to the senses, made less demand on his mental capacity, it suited him and enjoyed his particular favour.