Полная версия

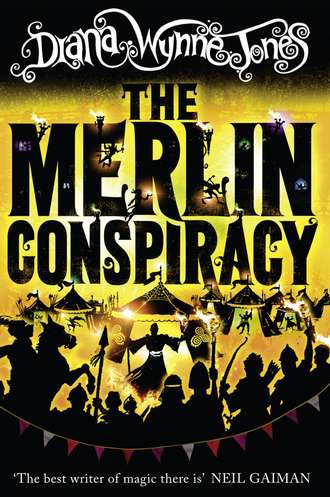

The Merlin Conspiracy

“Very well, as far as it goes,” he said in his weak, high voice. “You’ve got the King and his Court…”

“And all the other wizards. Don’t forget them,” Sybil put in pridefully.

Sir James chuckled. “None of them suspecting a thing!” he said. “They should be dancing to her tune now, shouldn’t they?”

“Yes. For a while,” the Merlin agreed, still looking around. “Is this where you put the spell on?”

“Well, no. It’s a bit strong here,” Sybil admitted. “I didn’t have time for the working it would take to do it here. I worked from the pool below the steps. That’s the first cistern the well flows out to, you see, and it feeds all the other channels from there.”

The Merlin went, “Hm.” He squatted down like a grasshopper beside the well and put his candle down by one of his gawky, bent legs. “Hm,” he went again. “I see.” Then he pulled open the lid over the well.

Grundo and I felt the power from where we stood. We found it hard not to sway. The Merlin got up and staggered backwards. Behind him, Sir James said, “Ouch!” and covered his face.

“You see?” said Sybil.

“I do,” said Sir James. “Put the lid back, man!”

The Merlin dropped the lid back with a bang. “I hadn’t realised,” he said. “That’s strong. If we’re going to use it, we’ll have to conjure some other Power to help us. Are there any available?”

“Plenty,” said Sir James. “Over in Wales particularly.” He turned to Sybil. The candlelight made his profile into a fleshy beak with pouty lips. “How about it? Can you do a working now? We ought to have this Power in and consolidate our advantage now we’ve got it.”

Sybil had pouty lips too. They put her chin in shadow as she said, “James, I’m exhausted! I’ve worked myself to the bone this evening and I can’t do any more! Even going barefoot all the time, it’ll be three days before I’ve recouped my powers.”

“How long before you can do a strong working?” the Merlin asked, picking his candle up. “My friend James is right. We do need to keep up our momentum.”

“If we both help you?” Sir James asked coaxingly.

Sybil hung her head and her hair down and thought, with her big arms planted along her large thighs. “I need three days,” she said at last, rather sulkily. “Whoever helps me, I’m not going to be able to tackle something as strong as this well before that. It won’t take just a minor Power to bespell the thing. We’ll have to summon something big.”

“But will the effect of the drink last until we do?” Sir James asked, rather tensely.

Sybil looked up at the Merlin. He said, “It struck me as firm enough for the moment. I don’t see it wearing off for at least a week, and we’ll be able to reinforce it before that.”

“Good enough.” Sir James sprang up, relieved and jolly. “Let’s get this place locked up again then and go and have a proper drink. Who fancies champagne?” He pulled keys out of his pocket and strode away down the steps, jingling them and lighting the trees to a glinting black with his candle.

“Champagne. Lovely!” said Sybil. She heaved to her feet and shoved the Merlin playfully down the steps in front of her. “Off you go, stranger boy!”

Grundo and I realised we were likely to get locked inside the garden. We nearly panicked. The moment Sybil was out of sight we surged out on to the flagstones and then realised that the only way out was down those same stone steps to the lopsided pool. That was almost the worst part of the whole thing. We had to wait for Sir James, Sybil and then the Merlin to get ahead, then follow them, and then try to get ahead of them before they got to the gate in the wall.

We were helped a lot by the queer way the space in the garden seemed to spread, and by all the stone walls and conduits and bushes. We could see Sir James and the other two easily by the light of their flickering candles – and hear them too, most of the time, talking and laughing. Sybil obviously was tired. She went quite slowly and the others waited for her. We were able to scud along behind lavender and tall, toppling flowers, or crouch down and scurry past pieces of old wall – though we couldn’t go really fast because it was quite dark by then – and finally we got in front of them and raced out through the gate just before they came merrily along under a rose arch.

I was a nervous wreck by then. It must have been even worse for Grundo, knowing his mother was part of a conspiracy. We went on running beside a dim path and neither of us stopped until we were well out into the lawns in the main garden and could see our camp in the distance, twinkling beyond the fence.

“What do we do now?” I panted at Grundo. “Tell my Dad?”

“Don’t be stupid!” he said. “He was there drinking with the other wizards. He’s not going to listen to you for at least a fortnight.”

“The King then,” I suggested wildly.

“He was the first one to drink,” Grundo said. “You’re not tracking.” He was right. Everything was all about in my head. I tried to pull myself together, not very successfully, while Grundo stood with his head bent and thought. “Your grandfather,” he said after a bit. “He’s the one to tell. Do you have his speaker code?”

“Oh. Right,” I said. “Mam will have his number. I can ask Dad to lend me his speaker at least, can’t I?”

Unfortunately, when we got to the camp we discovered that both Mam and Dad were up at the castle attending on the King. Though I could have asked all sorts of people to lend me a speaker, it was no good unless I knew the code. Grandad’s number is not in the directory lists.

“We’ll just have to wait till tomorrow,” I said miserably.

I spent a lot of that night tossing in my bunk in the girls’ bus, wondering how the new Merlin came to join with Sybil and Sir James, and how to explain to Grandad that he had chosen the wrong man for the post. It really worried me that Grandad had chosen this Merlin. Grandad doesn’t usually make mistakes. It worried me even more that I didn’t know what this conspiracy was up to. It had to be high treason. As far as I knew, bespelling the King was high treason anyway, and it was obvious that they meant to go on and do something worse.

I tossed and turned and tossed and thought, until Alicia suddenly sprang up and shouted, “Roddy, if you don’t stop jigging about this moment, I’ll turn you into a statue, so help me Powers Above!”

“Sorry,” I mumbled, and then, even lower, “Sneeze!” If Alicia hadn’t been there, I might have tried telling the other girls in the bus, but Alicia would go straight to Sybil. And Alicia had drunk that enchanted water along with the other pages. Heigh ho, I thought. Wait till tomorrow.

So I waited helplessly until it was too late.

I overslept. I dragged myself up and over to the food- tent, yawning. I had just got myself some juice and a cold, waxy-looking fried egg, when Grundo appeared, looking worried.

“There you are!” he said. “There’s a message for you from the Chamberlain.”

The Chamberlain had never noticed my existence before. Before I got over my surprise enough to ask Grundo what the message was, Mam dashed up to me from the other side. “Oh, there you are, Roddy! We’ve been hunting for you all over! Your grandfather wants you. He’s sent a car for you. It’s waiting for you now outside the castle.”

My first thought was that this was an answer to my prayers. Then I looked up at Mam’s face. She was so white that her eyes looked like big black holes. The hand she put on my shoulder was quivering. “Which grandfather?” I said.

“My father, of course,” she said. “It’s just like him to send a demand for you to the Chamberlain. I’m surprised he didn’t send it straight to the King! Oh, Roddy, I’m sorry! He’s insisting that you go and stay with him in that dreadful manse of his and I daren’t refuse! He’s already been dreadfully rude to the Chamberlain over the speaker. He’ll do worse than that if I don’t let you go. He’ll probably insult the King next. Forgive me.”

Poor Mam. She looked absolutely desperate. My stomach plunged about just at the sight of her. “Why does he want me?”

“Because he’s never met you, and you’re near enough to Wales here for him to send and fetch you,” Mam answered distractedly. “He’s told the entire Chamberlain’s Office that I’ve no right to keep his only grandchild from him. You’ll have to go, my love – the Chamberlain’s insisting – but be polite to him. For my sake. It’ll only be for a few days, until the Progress moves on after the Meeting of Kings. He says the car will bring you back then.”

“I see,” I said, the way you say things just to gain time. I looked at my fried egg. It looked back like a big, dead, yellow eye. Ugh. I thought of Grundo all on his own here, and Sybil discovering that he hadn’t drunk her charmed water. “I’ll go if I can take Grundo,” I said.

“Oh, really, my love, I don’t think…” Mam began.

“Listen, Mam,” I said. “Your problem was that he’s a widower and you were all on your own with him…”

“Well, that wasn’t quite…” she began again.

“…so you ought to allow me to take some moral support with me,” I said. As she wavered, I added, “Or I shall go to the Chamberlain’s Office and use their speaker to tell him I won’t go.”

This so horrified Mam that she gave in. “All right. But I don’t dare think what he’ll say – Grundo, do you mind being dragged along to see a fearsome old man?”

“Not really,” Grundo said. “I can always use the speaker in his manse to ask for help, can’t I?”

“Then go and pack,” Mam told him frantically. “Take old clothes. He’ll make you go for walks, or even ride – Hurry up, Roddy! He’s sent his same old driver who hates to be kept waiting!”

I didn’t see why Mam needed to be scared of her father’s driver as well as her father, but I drained my juice, snatched a piece of toast and rushed off eating it. Mam rushed with me, distractedly reminding me to remember a sweater, a toothbrush, walking shoes, a comb, my address book, everything… It wasn’t exactly the right moment to start telling her of plots and treason, but I did honestly try, after I had rammed things into a bag and we were rushing up the steep path to the castle, with stones spurting from under our feet and clattering down on Grundo, who was bent over under a huge bag behind us.

“Are you listening to me?” I panted, when I’d told her what we’d overheard.

She was so upset and feeling so strongly for me getting into the clutches of her terrible old father that I don’t think she did listen, even though she nodded. I just had to hope she would remember it later.

The car was drawn up in front of the main door of the castle, as if the driver, or Mam’s father, imagined that I was staying in there with the King. It was black and uncomfortably like a hearse. The “same old driver”, who looked as if he had been carved out of a block of something white and heavy and then dressed in navy blue, got out when he saw us coming and held out his big stony hand for my bag.

“Good morning,” I panted. “I’m sorry to have kept you waiting.”

He didn’t say a word, just took my bag and stowed it in the boot. Then he took Grundo’s bag with the same carved stone look. After that, he opened the rear door and stood there holding it. I saw a little what Mam meant.

“Nice morning,” I said defiantly. No answer. I turned to Mam and hugged her. “Don’t worry,” I said. “I’m a very strong character myself and so is Grundo. We’ll see you soon.”

We climbed into the back seat of the hearse and were driven away, both of us feeling a little dizzy at the speed of events.

Then we drove and drove and drove, until we were dizzy with that too. I still have not the least idea where we went. Grundo says he lost his sense of direction completely. All we knew were astonishingly green hills towering above grey, winding roads, grey stone walls like cross-hatching on the hillsides, grey slides of rock, and woods hanging over us from time to time like dark, lacy tunnels. Dad’s good weather was getting better and better, so there was blue, blue sky with a brisk wind sliding white clouds across it, and sliding their shadows over the green hills in strange, shaggy shapes. Under the shadows, we saw heather darken and turn purple again, gorse blaze and then look a mere modest yellow, and sun and shade pass swiftly across small roaring rivers half hidden in ravines.

It was all very beautiful, but it went on so long, winding us further and further into the heart of the green mountains – until we finally began winding upwards among them. Then it was all green and grey again, with cloud shadows, and we had no sense of getting anywhere. We both jumped with surprise when the car rolled to a stop on a flat green stretch near the top of a mountain.

The stone-faced driver got out and opened the door on my side.

This obviously meant Get out now, so we scrambled to the stony green ground and stood staring about. Below us, a cleft twisted among the emerald sides of mountains until it was blue-green with distance, and beyond those green slopes were blue and grey and black peaks, peak after peak. The air was the chilliest and clearest I have ever breathed. Everything was silent. It was so quiet, I could almost hear the silence. And I realised that, up to then, I had lived my entire life close to people and their noise. It was strange to have it taken away.

The only house in sight was the manse. It was built backed against the nearest green peak, but below the top of the mountain, for shelter, though its dark chimneys stood almost as high as the green summit. It was dark and upright and squeezed into itself, all high narrow arches. You looked at it and wondered if it was a house built like a chapel, or a chapel built like a house and then squeezed narrower. There was no sign of any garden, just that house backed into the hillside and a drystone wall sticking out from one end of it.

The stone driver was trudging across the grass with our bags to the narrow, arched front door. We followed him, through the door and into a tall, dark hallway. He had gone somewhere else by the time we got indoors. But we had only been standing a moment wondering what to do now, when a door banged echoingly further down the hall and my mother’s father came towards us.

He was tall and stiff and cold as a monument on a tomb. His black clothes – he was a priest of course – made his white face look pale as death, but his hair was black, without a trace of grey. I noticed his hair particularly because he put a chilly hand on each of my shoulders and turned me to the light from the narrow front door. His eyes were deep and black, with dark skin round them, but I saw he was a very handsome man.

“So you are the young Arianrhod,” he said, deep and solemn. “At last.” His voice made echoes in the hall and brought me out in gooseflesh. I began to feel very sorry for Mam. “You have quite a look of my Annie,” he said. “Did she let you go willingly?”

“Yes,” I said, trying not to let my teeth chatter. “I said I’d come provided my friend Gr— er… Ambrose Temple could come too. I hope you can find room for him.”

He looked at Grundo then. Grundo gave him a serious freckled stare and said “How do you do?” politely.

“I see he would be lonely without you,” my grandfather said.

He was welcome to think that, I thought, if only he would let Grundo stay. I was very relieved when he said, “Come with me, both of you, and I will show you to your rooms.”

We followed him up steep, dark stairs, where his gown flowed over the wooden treads behind his straight back, and then along dark, wooden corridors. I had a queer feeling that we were walking right into the hill at the back of the house, but the two rooms he showed us to had windows looking out over the winding green hills and they were both obviously prepared for visitors, the beds made-up and water steaming in big bowls on the washstands. As if my grandfather had known I would be bringing Grundo. My bag was in one room and Grundo’s was in the other.

“Lunch will be ready any moment,” my grandfather said, “and you will wish to wash and tidy yourselves first. But if you want a bath…” He opened the next door along and showed us a huge bathroom, where a bath stood on clawed animal feet in the middle of bare floorboards. “I hope you will give warning when you do,” he said. “Olwen has to bring up buckets from the copper.” Then he went away downstairs again.

“No taps,” said Grundo. “As bad as the bath-tent.”

We washed and got ready quickly. When we met in the corridor again, we discovered that we had both put on the warmest clothes we had with us. We would have laughed about it, but it was not the kind of house you liked to laugh in. Instead, we went demurely downstairs, to where my grandfather was waiting in a tall, chilly dining room, standing at the head of a tall, black table.

He looked at us, pointed to two chairs and said grace in Welsh. It was all rolling, thundering language. I was suddenly very ashamed not to understand a word of it. Grundo looked on calmly, almost as if he did understand, and sat quietly down when it was finished, still looking intently at my grandfather.

I was looking at the door, where a fat, stone faced woman was coming in with a tureen. I was famished by then and it smelled wonderful.

It was a very good lunch, though almost silent at first. There was the leek soup, enough for two helpings each, followed by pancakes rolled round meat in sauce. After that, there were heaps of little hot griddle cakes covered in sugar. Grundo ate so many of those that the woman had to keep making more. She seemed to like that. She almost had a smile when she brought in the third lot.

“Pancakes,” my grandfather said, deep and hollow, “are a traditional part of our diet in this country.”

I was thinking, Well, at least he didn’t starve my mother! But why is he so stiff and stern? Why doesn’t he smile at all? I’m sure my mother used to ask herself the same things several times a day. I was sorrier for her than ever.

“I know this is an awkward question,” I said, “but what should we call you?”

He looked at me in stern surprise. “My name is Gwyn,” he said.

“Should I call you Grandfather Gwyn then?” I asked.

“If you wish,” he said, not seeming to care.

“Might I call you that too, please?” Grundo asked.

He looked at Grundo long and thoughtfully, almost as if he was asking himself what Grundo’s heredity was. “I suppose you have a right to,” he said at last. “Now tell me, what do either of you know of Wales?”

The truthful answer, as far as I was concerned, was Not a lot. But I could hardly say that. Grundo came to my rescue – I was extremely glad he was there. Because Grundo has such trouble reading, he listens in lessons far more than I ever do. So he knows things. “It’s divided into cantrevs,” he said, “each with its lesser kings, and the Pendragon is High King over them all. The Pendragon rules the Laws. I know you have a different system of laws here, but I don’t know how they work.”

My grandfather looked almost approving. “And the meaning of the High King’s title?” he asked.

It felt just like having a test during lessons, but I thought I knew the answer to that. “Son of the dragon,” I said. “Because there is said to be a dragon roosting in the heart of Wales.”

This didn’t seem to be right. My grandfather said frigidly, “After a fashion. Pendragon is a title given to him by the English. By rights, it should be the title of the English King, but the English have forgotten about their dragons.”

“There aren’t any dragons in England!” I said.

He turned a face full of stern disapproval on me. “That is not true. Have you never heard of the red dragon and the white? There were times in the past when there were great battles between the two, in the days before the Islands of Blest were at peace.”

I couldn’t seem to stop saying the wrong thing, somehow. I protested, “But that’s just a way of saying the Welsh and the English fought one another.”

His black eyebrows rose slightly in his marble face. I had never known so much scorn expressed with so little effort. He turned away from me and back to Grundo. “There are several dragons in England,” he said to him. “The white is only the greatest. There are said to be more in Scotland, both in the waters and in the mountains, but I have no personal knowledge of these.”

Grundo looked utterly fascinated. “What about Ireland?” he asked.

“Ireland,” said my grandfather, “is in most places low and green and unsuitable for dragons. If there were any, Saint Patrick expelled them. But to go back to the Laws of Wales. We do not have Judges, as you do. Courts are called when necessary…”

He went into a long explanation. Grundo was still fascinated. I sat and watched their two profiles as they talked, Grundo’s all pale, long nose and freckles, and my grandfather’s like a statue from classical antiquity. My grandfather had quite a long nose too, but his face was so perfectly proportioned that you hardly noticed. They both had great, deep voices, though where Grundo’s grated and grunted, my grandfather’s voice rolled and boomed.

Soulmates! I thought. I was glad I’d brought Grundo.

At the same time, I began to see some more of my mother’s problem. If my grandfather had been simply cold and strict and distant, it would have been easy to hate him and stop there. But the trouble was that he was also one of those people you wanted to please. There was a sort of grandness to him that made you ache to have him think well of you. Before long, I was quite desperate for him to stop talking just to Grundo and notice me – or at least not disapprove of me so much. Mam must have felt exactly the same. But I could see that, no matter how hard she tried, Mam was too soft-hearted and emotional for her father, and so he treated her with utter scorn. He scorned me for different reasons. I sat at the tall table almost in pain, because I knew I was a courtier born and bred, and that I was smart and good-mannered and used to summing people up so that I could take advantage of their faults, and I could see that my grandfather had nothing but contempt for people like me. It really hurt. Grundo may have been peculiar, but he was not like that and my grandfather liked him.

It was an enormous relief to me when we were allowed to get up from the table and leave the tall cold room. My grandfather took us outside, through the front door, into a blast of sunlight and cold, clean air. While I stood blinking, he said to us, “Now, where would you say the red dragon lies?”

Grundo and I looked at one another. Then we pointed, hesitating a bit, to the most distant brown mountains, lying against the horizon in a misty, jagged row.

“Correct,” said my grandfather. “That is a part of his back. He is asleep for now. He will only arouse in extreme need, to those who know how to call him, and he does not like to be roused. The consequences are usually grave. The same is true of the white dragon of England. You call him too at your peril.” The way he said this made us shiver. Then he said, in a much more normal way, “You will want to explore now. Go anywhere you like, but don’t try to ride the mare and be back at six. We have tea then, not the dinner you are used to. I’ll see you at tea. I have work to do before then.”

He went back into the house. He had a study at the back of the hall, as we learnt later, though we never saw inside it. It was a bit puzzling really. We never saw him do any religious duties or see parishioners – there were no other houses for miles anyway – but as Grundo said, dubiously, we were not there on a Sunday or any other holy day, so how could we know?

We did find the chapel. It was downhill to the left of the house, very tiny and grey, with a little arch of stone on its roof with a bell hanging in it. It was surrounded in green, and there was a hump of green turf beside it like a big beehive, that had water trickling inside it. The whole place gave us an awed, uncertain feeling, so we went uphill again and round to the back of the house, where we came upon a stone shed with the car inside it. Beyond that, things were normal.