полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

“I inquired carefully about the shape and size of this unicorn, as I shall call it, and was told that it exactly resembled a stag.

“The horn was of a brownish colour, about one archæon or twenty-eight inches long, and twisted from the root till within a finger’s length of the tip, where it was divided, like a fork, into two points, very sharp.”

One of the most trustworthy of observers, the Abbé Huc, speaks very positively on the subject of the unicorn.295 He says: “The unicorn really exists in Thibet… We had for a long time a small Mongol Treatise on Natural History, for the use of children, in which a unicorn formed one of the pictorial illustrations… The Chinese Itinerary says, on the subject of the lake you see before your arrival at Atzder (going from east to west), ‘The unicorn, a very curious animal, is found in the vicinity of this lake, which is forty li long.’”

The unicorn is known in Thibet by the name of serou; in Mongolia, by that of kere; while in a Thibetan manuscript examined by the late Major Lattre, it is called the one-horned tsopo.

Mr. Hazlitt, in his notes appended to the statement by Huc as to the unicorn, states that Mr. Hodgson, of Nepaul, sent to Calcutta the skin and horn of a unicorn that died in the menagerie of the Rajah of Nepaul.

It was described as being very fierce, and abundant in the plains of Tingri, in the southern part of the Thibetan province of Tsang, watered by the Arroun; it assembled round salt beds. The form is graceful, colour reddish, two tufts of hair project from the exterior of each nostril, and there is much down round the hair and mouth. The hair is rough and seems hollow. Doctor Able designated it Antelope Hodgsonii.

Baron von Müller described,296 through the medium of M. Antoine d’Abbadie, a unicorn animal which he had received when at Melpes in Kordofan: —

“I met, on the 17th of April 1848, a man who was in the habit of selling to me specimens of animals. One day he asked me if I wished also for an a’nasa, which he described thus: ‘It is the size of a small donkey, has a thick body and thin bones, coarse hair, and tail like a boar. It has a long horn on its forehead, and lets it hang when alone, but erects it immediately on seeing an enemy. It is a formidable weapon, but I do not know its exact length. The a’nasa is found not far from here (Melpes), towards the south-southwest. I have seen it often in the wild grounds, where the negroes kill it, and carry it home to make shields from its skin.’ N.B.– This man was well acquainted with the rhinoceros, which he distinguished, under the name of fetit, from the a’nasa.

“On June the 14th I was at Kursi, also in Kordofan, and met there a slave merchant who was not acquainted with my first informer, and gave me spontaneously the same description of the a’nasa, adding that he had killed and eaten one long ago, and that its flesh was well flavoured.”

This creature is mentioned by Rupell, under the name of Nillekma or Arase, as indigenous to Kordofan, and, by Cavassi, as known in Congo under that of Abada.

Mr. Freeman, in the South African Christian Recorder (vol. i.), gives the native account of an animal not uncommon in Makooa, and called the Ndzoodzoo, described as being about the size of a horse, extremely fleet and strong, with a single horn from two feet to two and a half feet in length, projecting from its forehead, which is said to be flexible when the animal is asleep, and capable of being curled up at pleasure, but becoming stiff and hard under the excitement of rage. It is extremely fierce, and invariably attacks a man when it discerns him. The female is without a horn.

Our latest information as to this species comes from Prejevalski,297 who, speaking of it as the orongo, says that it has elegant black horns standing vertically above the head; the back is dun-coloured; the middle of the breast, stomach, and rump, white; seen at a distance it appears white; it is very numerous in Northern Thibet. He adds: “Another prevalent superstition is that the orongo has only one horn growing vertically from the centre of the head. In Kansu and Kokonor we were told that unicorns were rare, one or two in a thousand. The Mongols in Tsaidan deny it, but say it may be so in south-west Thibet.”

Turning to the Chinese classics and books of antiquity, we find references, sometimes vague and mythical, sometimes exact, to several distinct unicorn animals. These may be enumerated as: —

2981. The Ki-Lin, represented in Japan by the Kirin.

2. The King.

3. The Kioh Twan.

4. The Poh.

5. The Hiai Chai.

6. The Too Jon Sheu.

Besides these there are clear descriptions of the rhinoceros, which cannot in any way be confounded with the above. The only one of these popularly familiar is the Ki-Lin, the history of which is interwoven with that of remote ages. The first mention of it is made in the Bamboo Books – only in that part, however, of them which is apparently a commentary, note, or subsequent addition, though some authorities hold it to be a portion of the actual text. The work states that, during the reign of Hwang-Ti (B.C. 2697), Ki-Lins appeared in the parks.

Their appearance was generally supposed to signalise the reign of an upright monarch, and Confucius considered that the appearance of one during his epoch was a bad omen, as it did not harmonise with the troubled state of the times. The name Ki-Lin is a generic or dual word, composed of those of the Ki and the Lin, the respective male and female of the creature.

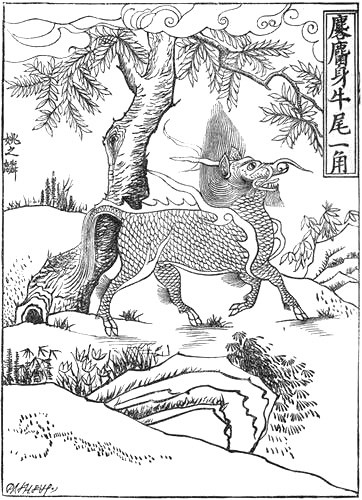

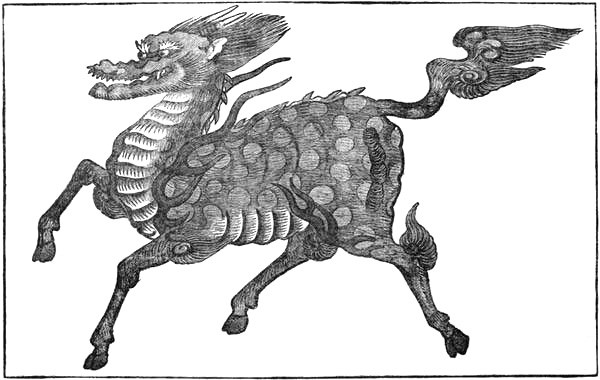

Fig. 79. – The Ki-Lin. (After a modern Chinese painting.)

This peculiar species of word formation is adopted in other instances in reference to birds and animals; thus we have the male Fung and the female Hwang united in the Fung Hwang, or so-called Chinese phœnix, and the Yuen and Yang in the Yuen Yang, or mandarin duck.

Sometimes the word Lin alone is used with the same generic meaning.

The ’Rh Ya, in the original text, defines the Lin as having a Kiun’s body (the Kiun is a kind of muntjack or deer), an ox’s tail, and one horn. The commentary states that the tip of the horn is fleshy, and that the King Yang chapter of the “Spring and Autumn Annals” of Confucius defines it as a horned Kiun.

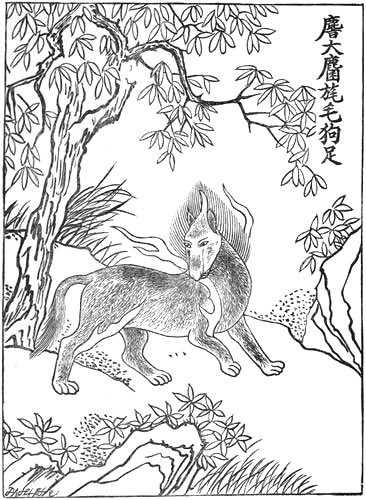

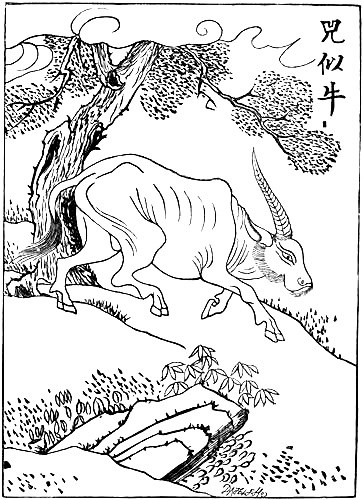

Fig. 80. – The Lin (female of the Chinese Unicorn).

(From the ’Rh Ya.)

The preface to the Shi Shu quotes Li Siün to the effect that the Lin is an auspicious and perfect beast.

Sun Yen says it is a spiritual beast. The Shwoh Wan says the Lin is the female of the K‘i and the K‘i is a beast endowed with goodness, possessing a Kiun’s body, an ox’s tail, and one horn. According to the Shwoh Wan, the Lin may be considered as a large female deer. Now the Shu King considers that many of these beasts are comprised under the Ki-Lin, only the characters, though retaining the sound, have become altered in form.

Cheu Nau calls it Lin-che-chi and Man Chw‘en says that the Lin is truthful, and reducible to rule.

The Li Yuen says: “If the unicorn can once be tamed, then the other beasts will not show terror.”

Ta Tai, in the Li Ki, quoting the Yih [King], says there are 360 kinds of hairy creatures, and the Ki-Lin is the chief of them.

The Li Ki, commenting on the King Fang I Chw‘en, says: “The Lin has a Kiun’s body, an ox’s tail, a horse’s hoof, and is of five colours. It is twelve feet high.”299

Again, in commenting on Fuh Kien’s Ho Chwen, it says: “The Lin springs from the earth’s central regions. It is a beast of superior integrity, is attached to its mother, and reducible to rule. The Shu King, quoting Luh Li, says the Lin has a Kiun’s body, an ox’s tail, a horse’s feet, and a yellow colour, round hoofs, and one horn; the tip of the horn is erect and fleshy.

“Its call in the middle part thereof is like a monastery bell. Its pace is regular; it rambles only on selected grounds and after it has examined the locality. It will not live in herds, or be accompanied in its movements. It cannot be beguiled into pitfalls, or captured in snares. When the monarch is virtuous, this beast appears.”

At present there are Lin existing on the frontiers of Ping Cheu. Even the large or small Lin are always like deer, so that this species is not the auspicious Ying Lin; although Tsz Ma Siang Su,300 in his odes on the shooting of the Mi and trapping Lin, says that it is.

The top of the horn being fleshy is a characteristic of the Lin, and Mao Chw‘en says that the Lin’s horn is an emblem of goodness. Ching Tsien says that the horn has a fleshy termination, indicating the peaceful character of the beast, and that it has no use for it.

The “Book of Rites,” quoting the Kwang Ya, says that on account of its elegant style it takes place, par excellence, among the large-horned beasts; the existing edition of the Kwang Ya omits this.

The Kung Yang Chw‘en says the Kiun also has horns.

Kung Ssun Tsz, in the annals of the fourteenth year of the Duke Ngai (State of Lu), says that the Kiun has fleshy horns.

Kwoh, in his preface, proves the Lin to have a Kiun’s body.

The ’Rh Ya gives the drawing of a unicorn animal called the Ki; but no reference to the horn is given in the text, which simply describes it as a large Kiun with a yak’s tail and dog’s feet.

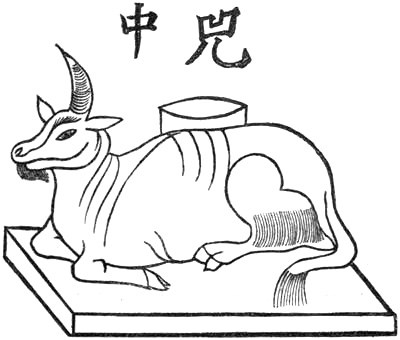

Fig. 81. – The Ki.

The Ki is not defined in the ’Rh Ya, and the only information I have as to it is derived from Williams’ dictionary, where it is stated to be “a fabulous auspicious animal, which appears when sages are born; the male of the Chinese unicorn. It is drawn like a piebald scaly horse, with one horn and a cow’s tail, and may have had a living original in some extinct equine animal.” But there is a very full account of an animal called the King. It is not impossible that it is identical with the King which, in the usual brief style of the original text of the ’Rh Ya, is epitomised as a large Biao (a kind of stag), with an ox’s tail and one horn; and the several commentaries on it are as follows: —

“In the time of the Emperor Wu, of the Han dynasty, during the worship of heaven and earth at the solstices at Yung, there was captured a unicorn beast like a Piao; it was at that time designated the Lin; it was, however, a Piao related to the Chang (a kind of deer).”

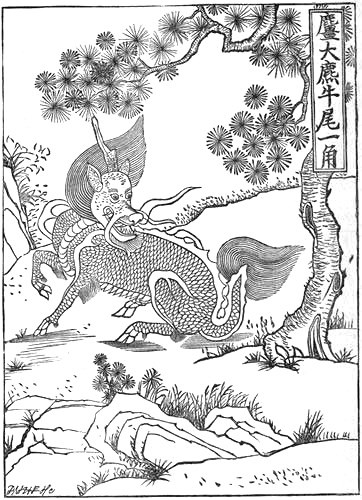

Fig. 82. – The King. (From the ’Rh Ya.)

The Shwoh Wan says: “The King is a large stag with an ox’s tail and one horn.” It may be a large form of the Piao. The Wang Hwu Analects say that the Piao is an object of the chase, and that it is as swift as a stag.

Kwan Tsz, in the Ti Yuen volume, says that as there are Mi and Piao and many species of deer, so also the Piao is a species of deer.

The “Shi Ki,” in the book Fung Shen, says that during the worship at the solstices at Yung, there was captured a one-horned beast like a Piao, and that the local authorities assert that as His Majesty was making reverential invocations on the country altar to the Supreme Being, he was recompensed for the sacrifice by a beast which was a unicorn.

Wu Chao’s preface to the Loh Yiu says: “The body is like that of a muntjack, and it has one horn”; while the Spring and Autumn (Annals) allude to this animal in speaking of the horned Kiun.

The inhabitants of Ch‘u say the Kiun is a Piao. Kwoh, in his preface, says that the capture made in the time of Wu, of the Han dynasty, was actually a Piao, as demonstrated by the Han books. The Chung Kiun narrative states that in Shang Yung was captured a white Lin bearing one horn, of which the tip was fleshy. At the present day nothing has been heard of a Piao with a fleshy tip, therefore these must be different beasts.

Kwoh also says that the Piao is identical with the Chang, and the Chang with the Kiun. This corresponds with what Wei Chao So had already stated, that the people of Ch‘u assert that the Kiun is a Piao, and that the Piao is certainly a kind of deer.

Its meat is eminently savoury.

Luh Ki says that of all four-footed creatures, the Piao is the most excellent.

Yeu Shi states in the Kiao Sz annals (“Sacrifices to Heaven and Earth”), that the Piao is a kind of deer. Its body exactly resembles that of the Chang.

Finally, the explanatory prefaces of many classical works, when commenting on the ’Rh Ya, say that the Piao is identical with the Chang and of a black colour; and they confirm Kwoh’s opinion, although the ’Rh Ya forgets to allude to the three characters denoting the black colour.

Fig. 83. – The Ki-Rin. (From a Japanese Drawing in a Temple at Kioto.)

It was probably some unicorn animal which is referred to in the General History of China, called the Tong Kien Kang Mu (vide Père de Mailla’s translation), as having been presented to the Emperor Yung Loh of the Ming dynasty, in A.D. 1415, by envoys from Bengal. De Mailla says it was called a Ki-Lin by the Chinese out of flattery.

Again, the same History says that in the succeeding year the kingdom of Malin sent as tribute a Ki-Lin similar to that from Bengal.

The Ki-Rin, a Japanese version of the Ki-Lin, is simply borrowed from Chinese sources. It is figured in the illustrated edition of the great Japanese Encyclopædia Kasira gaki zou vo Sin mou dzu wi tai sei,301 and represented, as in the Chinese drawings, as covered with scales; but it must be noted that nothing in any of the texts of either country warrants this furniture of the body.302

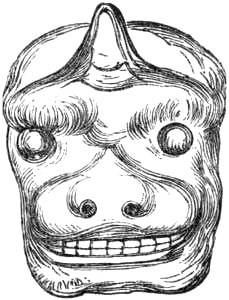

The same encyclopædia figures another unicorn beast under the name of the Kai Tsi, and describes it as being an animal of foreign countries, resembling a lion, and having a single horn. It is also called the Sin You or divine sheep. It is able to distinguish between right and wrong. When Kau You exercised criminal jurisdiction, he handed over those whose crime was doubtful to the Kai Tsu, and it is said that this animal destroyed the guilty and spared the innocent.

This is described in the Chinese work Yuen Kien Léi Han,303 under the name of the Hiai Chai, and similar powers of discrimination are there attributed to it.

Fig. 84. – The Sz, or Malayan Rhinoceros.

(From the ’Rh Ya.)

A synonym for it was the Chiai Tung. It states that, according to the Si Yang Y Shu, a one-horned spiritual lamb was born in the Ping Shen district, and in the twenty-first year of Kai Yuen. The horn was fleshy, and the top of the head covered with white hair. The second chapter on the same subject says that, in ancient times, if parties were at law, the judge brought this animal out, and it would gore at the guilty one.

The Kioh Twan is yet another unicorn animal described in the Yuen Kien Léi Han,304 which is said to have the appearance of a deer with the tail of a horse, but to be of a greenish colour, with one horn above the nose, and to be capable of traversing eighteen thousand li in one day.

The Li Kau Sing Sha Shao says that the Emperor Yuen Ti Su sent his ambassadors to the western part of India, who procured animals several tens of feet in height,305 unicorn, like the rhinoceros. The rumour went that these were inauspicious for the Emperor, and they were immediately returned.

The PohThe Shan Hai King describes an animal as existing among the plains of Mongolia, having the appearance of a horse, with a white body, black tail, one horn, teeth and claws like a tiger, which howls like the roll of a drum, devours tigers and leopards, and is capable of being used instead of soldiers; it is called Poh.

The ’Rh Ya describes the same animal as like a horse, with saw teeth, existing on tigers and leopards.

The “History of the North” says that in the Kingdom of Peh Chi (?) a magistrate named Chung Wa held office, who was very equitable in his rule. His district was invaded by some ferocious animals. Suddenly six of the Poh came and killed and devoured them as a reward for his good rule.

The Sung History says that a man named Leu Chang, an ambassador, arrived at a district called Shen Su, where the mountains contained a strange animal, in appearance like a horse, but capable of eating tigers and leopards. The people were unacquainted with it, and asked Leu Chang what it was, who said it was called the Poh, and referred them to the Shan Hai King for a description of it.

Fig. 85. – Target in the form of a Sphynx. (From the Sun Li T’u.).

The arrows were discharged upwards and fell into the cylinder behind the figure.

Among other remarkable and interesting drawings which have come down from antiquity in the San Li T’u,306 or illustrated edition of the three (ceremonial) rituals, are some representing the various targets used by officials of different ranks in the military examinations, in which the arrows had to be lodged by shooting upwards from a distance. These are fashioned in the form of animals, one realising the idea of the sphynx, and two representing unicorn animals, called respectively the Lu – which, according to some, is like an ass with one horn, but, according to others, differing from a donkey in having a cleft hoof – and the Sz, which is said to be like an ox with one horn.

Fig. 86. – The Lu Target. (From the San Li T’u.)

Fig. 87. – The Sz Target. (From the San Li T’u.)

Fig. 88. – The Too Jou Shen. (From the Ming Tombs.)

Fig. 89. – The Too Jou Shen.

(From the Ming Tombs.)

The Too Jou Shen is the name of an animal with a lion-like body and head, cloven hoofs, and a blunt short horn projecting from the centre of the forehead. Two pairs of these form a portion of the avenue of stone figures of animals leading up to the Ming tombs, about eighty miles north of Pekin. I have not found it described in any book.

A writer in the China Review307 endeavours to prove that the Ki-Lin is a reminiscence of the giraffe, which he supposes may once have spread over Asia, and, in addition to various passages included among those which I have quoted above, adduces one from the Wu Tsah Tsu, which states that, “In the period Yung Loh of the Ming dynasty (1403-1425) a Ki-Lin was caught, and a painter was ordered to make a sketch and hand it up to the high magistrates. According to the picture, the body was perfectly shaped like that of a deer, but the neck was very long, perhaps three or four feet.” I must admit that I cannot agree with him in his conclusions. Harris308 has given much better arguments in favour of the unicorn being merely a species of oryx. He appears to me, however, to speak too absolutely, to make his facts too pliant, and to base his main belief on the untenable theory that the myth, tradition, or theory is based on the profile drawing of an oryx, exhibiting one horn only. We might just as soon expect people to start stories of two-legged cows or horses, or one-legged races of men, if so slender a basis for forging a species were sufficient. What the zoological status of the unicorn may be I am not prepared to show, but I find it impossible to believe that a creature whose existence has been affirmed by so many authors, at so many different dates, and from so many different countries, can be, as mythologists demand, merely the symbol of a myth. There is a possible solution, which does not appear to have struck previous writers on the subject, viz., that the unicorn may be merely a hybrid produced occasionally and at more or less rare intervals.

By accepting this view we could explain the extraordinary combinations of character assigned to it, and the discrepancy which exists between the qualities of courage and gentleness ascribed to it by Western and Chinese authors. A valuable chapter remains to be written by naturalists and progressionists on the limits within which hybridization exists in a state of nature among the higher animals; its prevalence among the lower and among plants is, of course, well known. A cross between some equine and cervine species might readily result in a unicorn offspring, and either the courageous qualities of the sire309 or the gentleness of the dam might preponderate, according to the relations of the species in each of the instances.

As an alternative, we may speculate on the unicorn being a generic name for several distinct species of (probably) now extinct animals; missing links between the three families, the Equidæ, Cervidæ, and Bovidæ; creatures which were the contemporaries of prehistoric man, and which, before they finally expired, attracted the attention of his descendants, during early historic times, by the rare appearance of a few surviving individuals.

The supernatural qualities ascribed to these by various nations must be considered merely the embroidery of fancy, designed to enrich and adorn an article esteemed rare and valuable.

CHAPTER XI.

THE CHINESE PHŒNIX

From the date of the earliest examination of the literature of China, it has been customary among Sinologues to trace a fancied resemblance between a somewhat remarkable bird, which occupies an important position in the early traditions of that Empire, and the phœnix of Western authors. Some mythologists have even subsequently concluded that the Fung Hwang of the Chinese, the phœnix of the Greeks, the Roc of the Arabs, and the Garuda of the Hindoos, are merely national modifications of the same myth. I do not hold this opinion, and, in opposing it, purpose, in the future, to discuss each of these birds in detail, although in the present volume I treat only of the Fung Hwang.

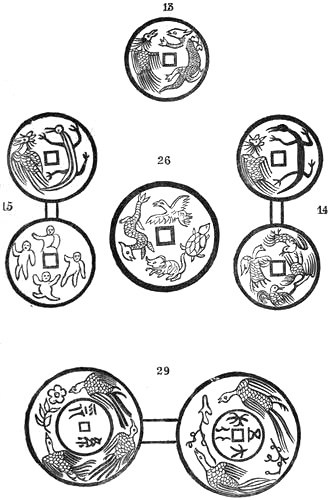

Fig. 90. – Temple Medals from China: Dragon and Phœnix.

The earliest notice of it is contained in the ’Rh Ya, which, with its usual brevity, simply informs us that the male is called Fung and the female Hwang; the commentator, Kwoh P‘oh, adding that the Shui Ying bird (felicitous and perfect – a synonym for it) has a cock’s head, a snake’s neck, a swallow’s beak, a tortoise’s back, is of five different colours, and more than six feet high. The ’Rh Ya Chen I, a later and supplementary edition of the former work, quotes the Shwoh Wan to the effect that the united name of the male and female bird is Fung Hwang, and that Tso’s commentary on the 17th year of the Chao, says one appeared in the time of the Emperor Che (dynastic title, Shaou Haou). The original passage in the Tso Chuen is so interesting that I quote in extenso Dr. Legge’s translation of it: —

“When my ancestor, Shaou-Haou Che, succeeded to the kingdom, there appeared at that time a phœnix, and therefore he arranged his government under the nomenclature of birds, making bird officers, and naming them after birds. There were so and so Phœnix bird, minister of the calendar; so and so Dark bird [the swallow], master of the equinoxes; so and so Pih Chaou [the shrike], master of the solstices; so and so Green bird [a kind of sparrow], master of the beginning (of spring and autumn); and so and so Carnation bird [the golden pheasant], master of the close (of spring and autumn)… The five Che [Pheasants] presided over the five classes of mechanics.