полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

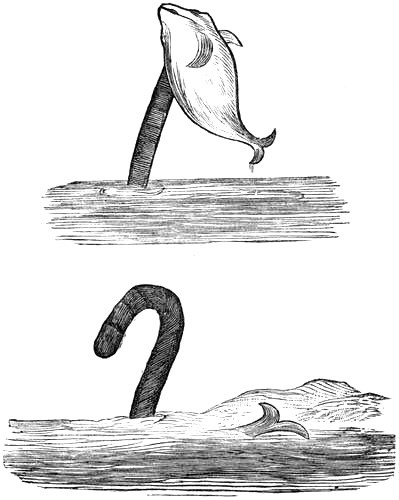

Fig. 75. – Sea-Serpent attacking Whale.

(From Sketches by Capt. Davidson, S.S. “Kiushiu-maru.”)

A remarkable and independent corroboration of modern date comes from the Japan seas. It was reported both in local papers and in the San Francisco Californian Mail-Bag for 1879, from which I extract the notice and the illustrative cuts (Fig. 75).

“The accompanying engravings are fac-similes of a sketch sent to us by Captain Davidson, of the steamship Kiushiu-maru,269 and is inserted as a specimen of the curious drawings which are frequently forwarded to us for insertion. Captain Davidson’s statement, which is countersigned by his chief officer, Mr. McKechnie, is as follows: —

“‘Saturday, April 5th, at 11.15 A.M., Cape Satano distant about nine miles, the chief officer and myself observed a whale jump clear out of the sea, about a quarter of a mile away.

“‘Shortly after it leaped out again, when I saw there was something attached to it. Got glasses, and on the next leap distinctly saw something holding on to the belly of the whale. The latter gave one more spring clear of the water, and myself and chief officer then observed what appeared to be a creature of the snake species rear itself about thirty feet out of the water. It appeared to be about the thickness of a junk’s mast, and after standing about ten seconds in an erect position, it descended into the water, the upper end going first. With my glasses I made out the colour of the beast to resemble that of a pilot fish.’”

There is an interesting story270 of a fight between a water-snake and a trout, by Mr. A. W. Chase, Assistant United States Coast Survey, which, magnis componere parva, may be accepted as an illustration of how a creature of serpentine form would have to deal with a whale; only, as on the surface or in mid-water it would be prevented from grasping any rocks by which to anchor itself, we may readily conceive it holding on with a tenacious grip of its extended jaws, and drawing itself up to the enemy until it could either embrace it in its coils or stun it with violent blows of the tail.271

“The trout, at first sight, was lying in mid-water, heading up stream. It was, as afterwards appeared, fully nine inches in length… This new enemy of the trout was a large water-snake of the common variety, striped black and yellow. He swam up the pool on the surface until over the trout, when he made a dive, and by a dexterous movement seized the trout in such a fashion that the jaws of the snake closed its mouth. The fight then commenced. The trout had the use of its tail and fins, and could drag the snake from the surface; when near the bottom, however, the snake made use of its tail by winding it round every stone or root that it could reach. After securing this tail-hold, it could drag the trout towards the bank, but on letting go the trout would have a new advantage. This battle was continued for full twenty minutes, when the snake managed to get its tail out of the water and clasped around the root of one of the willows mentioned as overhanging the pool. The battle was then up, for the snake gradually put coil after coil around the root, with each one dragging the fish toward the land. When half its body was coiled it unloosed the first hold, and stretched the end of its tail out in every direction, and finding another root, made fast; and now, using both, dragged the trout on the gravel bank. It now had it under control, and, uncoiling, the snake dragged the fish fully ten feet up on the bank, and, I suppose would have gorged him,” &c. &c.

Captain Drevar follows Pontoppidan (probably unwittingly) in identifying the sea-serpent with the leviathan of Scripture, quoting Isaiah xxvii. 1, “In that day the Lord with his sore and great and strong sword shall punish leviathan, the piercing serpent, even leviathan that crooked serpent; and he shall slay the dragon that is in the sea.” As I read the above passage, it is the dragon that is in the sea, and not the leviathan, which should be identified with the sea-serpent, unless the two, dragon and leviathan, are in apposition, which does not seem to be the case.

These various narratives which I have collected are, for the most part, well attested by the signature, or declaration on oath, of well-known and responsible people. Captain Drevar, in the small pamphlet which he had printed for private circulation, says: “Does any thinking person imagine I could keep command over men with a deliberate lie in our mouths?” and a similar question may be asked, with, I think, the possibility of only one reply, in the case of the narratives of Captain M’Quhœ and other officers and commanders in various navies and merchant vessels, and of the numerous other reputable witnesses who have affirmed, either as a simple statement or on oath, that they have seen sundry remarkable sea-monsters. I used the expression, “I think,” because, of course, there is the possibility of scepticism.

“Authority, in matters of opinion, divides itself (say) into three principal classes: there is the authority of witnesses; they testify to matters of fact. The judgment upon these is commonly, though not always, easy; but this testimony is always the substitution of the faculties of others for our own, which, taken largely, constitutes the essence of authority.

“This is the kind which we justly admit with the smallest jealousy. Yet not always; one man admits, another refuses, the authority of a sea-captain and a sailor or two on the existence of a sea-serpent.”272

I, for my part, belong to the former of these two categories. I believe in the statements that I have recorded, and in the following reasoning address only those who do likewise.

That mistakes have occasionally occurred is undoubted. Mr. Gosse records two instances in which long patches of sea-weed so far excited the imagination of captains of vessels as to cause them to lower boats and proceed to the attack.

The credibility of ghost stories generally is much affected when supposed apparitions are investigated and traced to some simple cause; and the hypersceptical may argue on parallel grounds that the transformation, in some few instances, of a supposed sea-serpent into sea-weed, or the admission of the plausible suggestion that it has been simulated by a seal, a string of porpoises, or some other very ordinary animals, largely affects the whole question.

And this would undoubtedly be the case if the conditions of the several examples were at all similar. But the hesitation or temporary misapprehension of captains or crews, in a thousand instances, as to the nature of a string of weed, supine on the surface, and lashed into fantastic motion by the surge of the ocean waves, has absolutely no bearing on the positive stories of a creature which is seen in calm fjords and bays to roll itself coil after coil, uplift its head high above the water, exhibit capacious jaws armed with teeth, conspicuous eyes, and paws or paddles, which pursues and menaces boats, presents a tangible object to a marksman, and when struck disappears with a mighty splash.

The probability of a gigantic seal, or of a string of porpoises, being mistaken for a sea-serpent by post-captains and their officers in the Navy is small, but becomes almost, if not quite, impossible when the observers are fishermen on coasts like those of Norway, who have been in the habit of seeing seals and porpoises almost every day of their lives. We may, therefore, freely grant that occasional mistakes have arisen, just as we have admitted that undoubtedly many hoaxes have been indulged in.

A rational and commonplace explanation is quite possible in some cases, as, for example, in that of a creature of abnormal appearance seen by the crew of Her Majesty’s yacht, the Osborne, in the Mediterranean, which was suggested, with great probability, to have been, if I remember correctly, some species of shark; while the supposed sea-serpent, washed up on the Isle of Stronsa, in 1808, proved, on scientific examination, to be a shark of the genus Selache, probably belonging to the species known as “the barking shark.”

The great oceanic bone shark, known to few except whalers, which has been stated to reach as much as sixty feet in length, may also occasionally have originated a misconception; and there must be still remaining in the depths of the ocean undescribed species of fish, of bizarre form, and probably gigantic size, the occasional appearance of which would puzzle an observer.

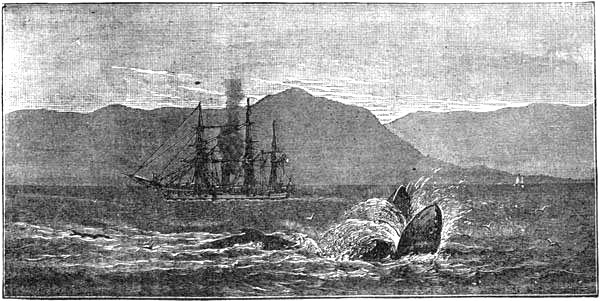

For example, in November 1879, an illustration was given in the Graphic of “another marine monster,” professing to be a sketch in the Gulf of Suez from H.M.S. Philomel, accompanied by the following descriptive letter-press: —

“This strange monster,” says Mr. W. J. Andrews, Assistant Paymaster, H.M.S. Philomel, “was seen by the officers and ship’s company of this ship at about 5.30 P.M. on October 14, when in the gulf of Suez, Cape Zafarana bearing at the time N.W. seventeen miles, lat. 28° 56′ N., long. 32° 54′ E.

“When first observed it was rather more than a mile distant on the port bow, its snout projecting from the surface of the water, and strongly marked ripples showing the position of the body. It then opened its jaws, as shown in the sketch, and shut them again several times, forcing the water from between them as it did so in all directions in large jets. From time to time a portion of the back and dorsal fin appeared at some distance from the head. After remaining some little time in the above-described position, it disappeared, and on coming to the surface again it repeated the action of elevating the head and opening the jaws several times, turning slowly from side to side as it did so.

Fig. 76. – Another Marine Monster. A Sketch in the Gulf of Suez, from

H.M.S. “Philomel,” Oct. 14, 1879. (From the “Graphic,” Nov. 1879.)

“On the approach of the ship the monster swam swiftly away, leaving a broad track like the wake of a ship, and disappeared beneath the waves.

“The colour of that portion of the body that was seen was black, as was also the upper jaw. The lower jaw was grey round the mouth, but of a bright salmon colour underneath, like the belly of some kinds of lizard, becoming redder as it approached the throat. The inside of the mouth appeared to be grey with white stripes, parallel to the edges of the jaw, very distinctly marked. These might have been rows of teeth or of some substance resembling whalebone. The height the snout was elevated above the surface of the water was at least fifteen feet, and the spread of the jaws quite twenty-five feet.”

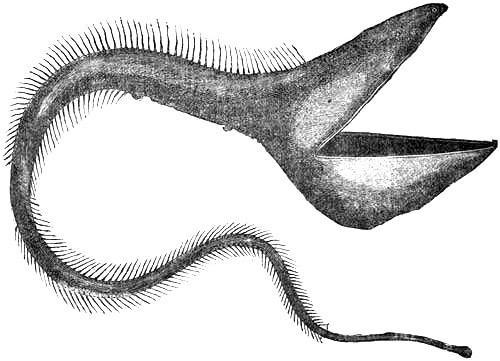

Strangely enough, a proximate counterpart of this fish, but of mimic size, was made known to science in 1882. My attention was called by Mr. Streich, of the German Consulate in Shanghai, to a description of this in the Daheim, an illustrated family paper, published in Leipzig, with an illustrative figure, from which I inferred that the monster seen by the crew of the Philomel was only a gigantic and adult specimen of a species belonging to the same order, perhaps to the same genus, as the Eurypharynx, adapted to live in the depths of the ocean, and only appearing upon the surface rarely and as the result of some abnormal conditions. I give fac-similes of both engravings, in order that my readers may draw their own comparison. The letter-press of the Daheim is as follows: —

“A New Fish.273“The deep-sea explorations of last year, which extended over eight thousand metres in depth, brought to light some very extraordinary animals, of which, up to the present date, we have no idea. The most curious one was found by the French steamer Le Travailleur, on which there was a staff of naturalists, and of the number was M. Milne Edwards. They were entirely devoted to deep-sea dredging.

“Between Morocco and the Canary Islands, at two thousand three hundred metres depth, the dredge caught a most wonderful animal, which at the first glance nobody thought to be a fish. This fish, of which we give here a picture, dwells on the bottom of the sea where the water is +5 °Celsius,274 in a kind of red slime composed of the shells of small Globigerinæ. On account of its curious mouth it has been called Eurypharynx Pelicanoides, i. e. the Pelican-like Broad-jaws. This creature is distinguished from all its class by the peculiar construction of its mouth, its under jaw being of a structure different from that of any other fish, possessing only two small teeth and a big pouch of most expansible skin, similar to the sac which a pelican has on its under jaw. In this sac it (the Broad-jaw) collects its food, and as its stomach is of very small dimensions, we may, from analogy with other fishes, conclude that it digests partly in this sac.

Fig. 77. – Eurypharynx Pelicanoides. (From the Daheim.)

“The swimming apparatus of this fish is not much developed, and reduced to a number of spines erect from the back and the belly.

“The pectoral fins, which are immediately behind the eye, are also very small, so that we may conclude from this that this fish does not move much, and is not a good swimmer.

“It only inhabits the bottom of the sea. Its body decreases gradually backwards till it finishes in a string-like tail. The organs for breathing are not much developed. Six slits (gill apertures?) allow the water to enter.

“The colour of the fish (the size of which we do not find in our authority) is velvet black.”

Before proceeding further I must point out that we may dismiss from our minds the possibility of the so-called sea-serpent being merely a large example of those marine serpents of which several species and numerous individuals are known to exist on the coast of many tropical countries, for these are rarely more than from four to six feet in length, although Dampier275 mentions one which he saw on the northern coast of Australia, which was long (but the length is not specified) and as big as a man’s leg. He gives a curious instance of these biters being bit, which he observed not far from Scoutens Island, off New Guinea: —

“On the 23rd we saw two snakes, and the next morning another passing by us, which was furiously assaulted by two fishes that had kept in company five or six days. They were shaped like mackerel, and were about that bigness and length, and of a yellow-greenish colour. The snake swam away from them very fast, keeping his head above water. The fish snapped at his tail; but when he turned himself that fish would withdraw and another would snap; so that by turns they kept him employed. Yet he still defended himself, and swam away at a great pace, till they were out of sight.”

Leguat276 speaks of a marine serpent, over sixty pounds in weight, which he and his comrades in misfortune captured and tasted, when marooned by order of the Governor of the Mauritius on some small island off the harbour, about six miles from the shore. He says: —

“It was a frightful sea-serpent, which we in our great simplicity took for a large lamprey or eel. This animal seemed to us very extraordinary, for it had fins, and we knew not that there were any such creatures as sea-serpents. Moreover, we had been so accustomed to discover creatures that were new to us, both at land and at sea, that we did not think this to be any other than an odd sort of eel that we never had seen before, yet which we could not but think more resembled a snake than an eel. In a word, the monster had a serpent or crocodile’s head, and a mouth full of hooked, long and sharp teeth… When our purveyors came we related to them what had happened to us, and showed them the eel’s head, but they only said they had never seen the like.”

In spite of Leguat’s impression, I think it was only some species of conger eel.

Marine serpents are abundant on the Malay coast, and particularly so in the Indian Ocean. Niebuhr says: —

“In the Indian Ocean, at a certain distance from land, a great many water-serpents, from twelve to fifteen inches in length, are to be seen rising above the surface of the water. When these serpents are seen they are an indication that the coast is exactly two degrees distant. We saw some of these serpents, for the first time, on the evening of the 9th of September; on the 11th we landed in the harbour of Bombay.”277

These sea-snakes are reputed to be mostly, if not entirely, venomous. Their motion in the water is by undulation in a horizontal, not in a vertical, direction; they breathe with lungs; their home is on the surface, and they would perish if confined for any considerable period beneath it.

Fig. 78. – Scoliophis Atlanticus. Killed on the Sea-shore near Boston, in 1817, and at that time supposed to be the young of the Sea-Serpent.

It is an open question whether conger eels may not exist, in the ocean depths, of far greater dimensions than those of the largest individuals with which we are acquainted. Major Wolf, who was stationed at Singapore while I was there in 1880, gave me information which seems to corroborate this idea. He stated that when dining some years before with a retired captain of the 39th Regiment, then resident at Wicklow, the latter informed him that, having upon one occasion gone to the coast with his servant in attendance on him, the latter asked permission to cease continuing on with the captain in order that he might bathe. Having received permission, he proceeded to do so, and swam out beyond the edge of the shallow water into the deep. A coastguardsman, who was watching him from the cliff above, was horrified to see something like a huge fish pursuing the man after he had turned round towards the shore. He was afraid to call out lest the man should be perplexed. The man, however, heard some splash or noise behind him, and looked round and saw a large head, like a bull-dog’s head, projecting out of the water as if to seize him. He made a frantic rush shoreways, and striking the shallow ground, clambered out as quickly as possible, but broke one of his toes from the violence with which he struck the ground. This story was confirmed by a Mr. Burbidge, a farmer, who stated that on one occasion when he himself was bathing within a mile or so of the same spot, the water commenced swirling around him, and that, being alarmed, he swam rapidly in, and was pursued by something perfectly corresponding with that described by the other narrator, and which he supposed to be a large conger eel. In each case the length was estimated at twenty feet. Mr. Gosse gives the greatest length recorded at ten feet.

Were we only acquainted with a small and certain proportion of the sea-serpent stories, we might readily imagine that they had been originated by a sight of some monstrous conger, but there are details exhibited by them, taken as a whole, which forbid that idea. We must therefore search elsewhere for the affinities of the sea-serpent.

And first as to those authorities who believe and who disbelieve in its existence.

Professor Owen, in 1848, attacked the Dædalus story in a very masterly manner, and extended his arguments so as to embrace the general non-probability of other stories which had previously affirmed it. He was, in fact, its main scientific opponent.

Sir Charles Lyell, upon the other hand, was, I believe, persuaded of its existence from the numerous accounts which he accumulated on the occasion of his second visit to America, especially evidence procured for him by Mr. J. W. Dawson, of Pictou, as to one seen, in 1844, at Arisaig, near the north-east end of Nova Scotia, and as to another, in August 1845, at Merigomish, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Agassiz also gave in his adhesion to it. “I have asked myself, in connection with this subject, whether there is not such an animal as the sea-serpent. There are many who will doubt the existence of such a creature until it can be brought under the dissecting knife; but it has been seen by so many on whom we may rely, that it is wrong to doubt any longer. The truth is, however, that if a naturalist had to sketch the outlines of an icthyosaurus or plesiosaurus from the remains we have of them, he would make a drawing very similar to the sea-serpent as it has been described. There is reason to think that the parts are soft and perishable, but I still consider it probable that it will be the good fortune of some person on the coast of Norway or North America to find a living representative of this type of reptile, which is thought to have died out.”

Mr. Z. Newman was the first scientific man to absolutely affirm his belief in its existence, and to indicate its probable zoological affinities; and he was ably followed by Mr. Gosse, who, in the charming work278 already frequently quoted, exhaustively discusses the whole question.

Mr. Gosse, however, to my mind, forgoes a great portion of the advantage of his argument by a too limited acceptance of authorities, and leaves untouched, as have all who preceded him, the question of the breathing apparatus of the creature, and also omits insisting, as he might well have done, on the remarkable coincidence of the seasons and climatic conditions at and under which the creature ordinarily exhibits itself, which may be quoted first as an argument in favour of the reality of the different stories, and, secondly, as affording indications of the nature and habits of the creature to which they relate.

Both Mr. Newman and Mr. Gosse, moreover, laboured under the disadvantage of being unacquainted with some of the later stories, such as that of the Nestor sea-serpent seen in the Straits of Malacca, which appears to amply substantiate the general conclusion at which they had already, happily, as I conceive, arrived.

In nearly all the cases quoted, and in all of those where the creature has appeared in the deep fjords of Norway or in the bays of other coasts, the date of its appearance has been some time during the months of July and August, and the weather calm and hot. These last summer conditions, in high latitudes, do not obtain for long together, so that the auspices favourable to the appearance of the creature would probably not exist for more than a few weeks in each season, and during the remainder of the year it would rest secluded in the depths of the fjords, presuming those to be its permanent habitation, or in some oceanic home, if, as would seem more likely to be the case, its appearance in the bays and fjords was simply due to a temporary visit, made possibly in connection with its reproduction; for, were its habitation in the fjords constant, we should expect it to make its appearance annually, instead of at irregular and distant intervals.

We must also infer that it is a non-air-breathing creature.

Professor Owen, in his very able discussion of the Dædalus story, bases his main argument against the serpentine character of the creature seen in this and other instances on there being either no undulation at all of the body, or a vertical one, which is not a characteristic of serpents, and on the fact of no remains having ever been discovered washed up on the Norway coasts. He says: —

“Now, a serpent, being an air-breathing animal, with long vesicular and receptacular lungs, dives with an effort, and commonly floats when dead, and so would the sea-serpent, until decomposition or accident had opened the tough integument and let out the imprisoned gases… During life the exigencies of the respiration of the great sea-serpent would always compel him frequently to the surface; and, when dead and swollen, it would

Prone on the flood, extended long and large,Lie floating many a rood.Such a spectacle, demonstrative of the species if it existed, has not hitherto met the gaze of any of the countless voyagers who have traversed the seas in so many directions.”

But, assuming it to be neither a serpent nor an air-breathing creature, the very cogent arguments which he applied so powerfully fall to the ground, and I may at once state that a review of the whole of the reported cases of its appearance entirely favours the first assumption, while a little reflection will show the necessity of the latter. No air-breathing creature, or rather a creature furnished with lungs, could possibly exist, even for a season only, in the inland bays of populous countries like Norway and Scotland without continually exposing itself to observation; but this is not the case. Whereas there is no difficulty in conceiving that a creature adapted to live in the depths of the ocean could breathe readily enough at the surface, even for considerable periods; for we know that fish of many kinds, and notably carp, can retain life for days, and even weeks, when removed from the water, provided they happen to be in a moist situation.