полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

The drawings made by Kwoh P‘oh appear to have been lost in the sixth century A.D.

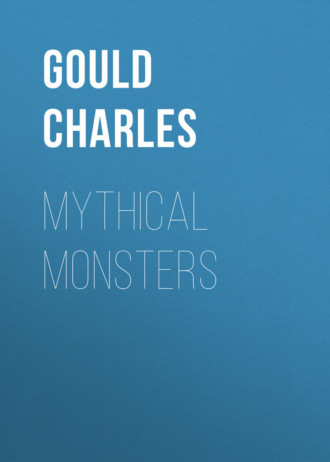

Fig. 42. – The K’i with Bells.

(From the ’Rh Ya.)

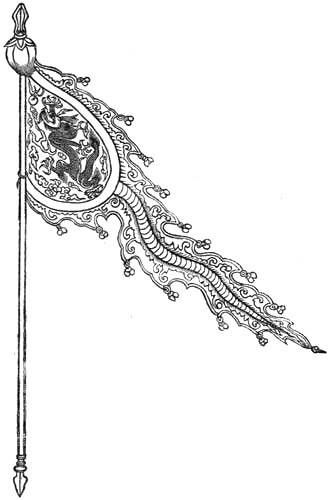

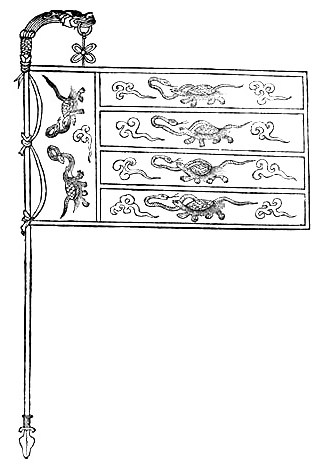

Notices of the dragon only appear incidentally in the ’Rh Ya as forming part of the decoration of banners, &c.; but descriptions and figures of the Chinese unicorn are given, and of other remarkable animals, of which I shall eventually take notice.

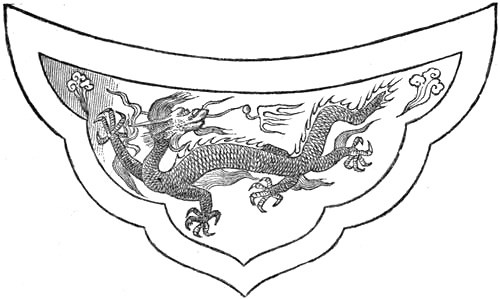

These figures of dragons in the drawings of banners (Figs. 41-44) are especially interesting; as there is fair reason to suppose that they at least have been reproduced time after time from pre-existing ones with tolerable accuracy; and that they give us a good notion of the general character of the animal they purport to represent.

Fig. 43. – The Chao Banner.

(From the ’Rh Ya.)

Fig. 44. – The K’i or KiaoLung Standard.

(From the San Li Tu.)

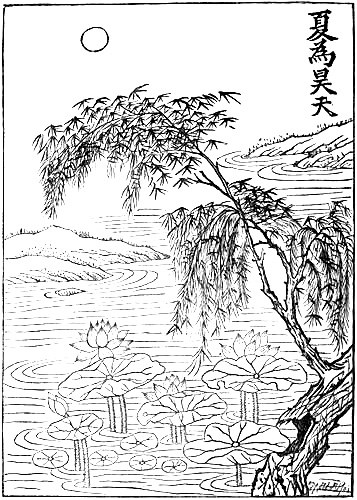

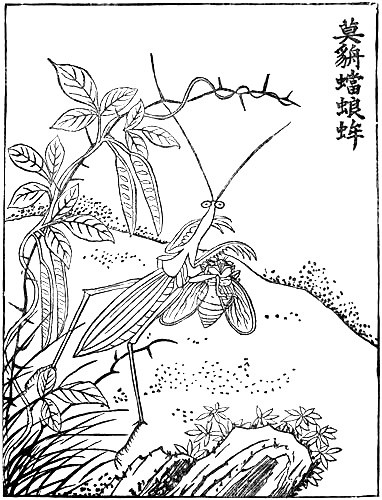

I have appended a few fac-similes of wood engravings from the ’Rh Ya on general subjects, in anticipation of others dealing with specialities, which will be found in their appropriate positions; they will serve to correct the notion that the Chinese are entirely devoid of artistic power and imagination (Figs. 46-49).

The “Shan Hai King” or Classic of Mountain and SeasShort notices of this remarkable work are given by Mr. Alexander Wylie236 and Dr. Bretschneider,237 and a more exhaustive one by M. Bazin.238

Fig. 45. – One of the Eave Tiles from the Old Imperial Palace of Nankin, showing the Five-clawed or Imperial Dragon, an emblem which cannot be borne by any outside of the Imperial service, under the penalty of death. Commoners have to be satisfied with a four-clawed dragon.

Fig. 46. – Return from the Chase. (From the ’Rh Ya.)

It is also largely quoted by Williams in his valuable Chinese dictionary. Otherwise Sinologues appear to have entirely ignored it.

Mr. Wylie remarks that “it has long been looked upon with distrust; but some scholars of great ability have recently investigated its contents, and come to the conclusion that it is at least as old as the Chow dynasty, and probably of a date even anterior to that period.”

M. Bazin speaks of it as a fabulous description of the world, and attributes it to Taouist writers in the fourth century of our era, who forged the authority of the great Yü and Peh Yi. He thinks it would be useless to attempt the identification of the localities given in it, and offers a translation of a portion of the first chapter in support of his views.

The value of his translation is impaired by his making no distinction between the text and the commentary, and he appears to have possessed an inferior and incomplete version.

In an editorial article in the North China Herald of May 9, 1884 (presumably by Mr. Balfour, an excellent Sinologue), it is referred to the date of Ch’in Shih Huang, who connected the Heptarchy into a single kingdom, and conquered Cochin China about B.C. 222.

Kwoh Po‘h239 (A.D. 276-324), who prepared an edition which has descended to us, ascribes a date to it 3,000 years anterior to his time.

Liu Hsiu,[241] of the Han dynasty (B.C. 206 to A.D. 25), states that the Emperor Yü, the founder of the Hia dynasty (B.C. 2205), employed Yih and Peh Yi as geographers and natural historians, who produced the “Book of Wonders by Land and Sea.” While Yang Sun,[241] of the Ming dynasty (commencing A.D. 1368), states in his after-preface that the Emperor Yü had nine metal vases cast, on which all wonderful or rare animals were engraved, the commoner ones being recorded in the annals of Yü; and that K‘ung Kiah (of the Hia dynasty, B.C. 1879), included this varied information in the present work.

Fig. 47. – One Mode of capturing Fish. (From the ’Rh Ya.)

Fig. 48. – Summer. (From the ’Rh Ya.)

It is to be hoped that at no distant date some competent Sinologue will be induced to furnish a full translation of this remarkable work, with an adequate commentary.

There is no doubt that many would be deterred from doing so by an impression that a collection of fabulous stories, treating of supernatural beings and apparently impossible monsters, is unworthy the consideration of mature intellect, and only fit to be relegated to the domain of Jack the Giant Killer and other childish stories. After a close examination of the book, I apprehend that this view of it can hardly be maintained. That such stories or descriptions are interspersed throughout the work is not to be disputed; but a large proportion of it consists of apparently authentic geographical records, including, as is customary with all works of a similar nature in China, descriptions of the most remarkable objects of natural history occurring in the different regions. I think it will be found possible to identify many of these at the present day, some may be conjectured at, and the residue are not more numerous in proportion than the similar fables or perverted accounts which figure in the western classic volumes of Ctesias, Aristotle, Pliny, and even much later writers. So far as the supernatural portions are concerned, it must be remembered that, even so late as the days of the childhood of Sir Humphrey Davy, pixies were still supposed by the lower classes to trace the fairy rings in Cornwall; that quite lately, and perhaps among certain classes to the present day, the existence of the banshee in Ireland, of the kelpie in Scotland, and of persons gifted with the mysterious and awe-inspiring power of second sight, was religiously believed in. There are few important houses in England whose ancestral walls have not concealed an apparition connected with the destinies of the family, appearing only on fatal or eventful occasions; and in the days of the sapient James I. in England, and among the Pilgrim Fathers in the American States, the existence of wizards and witches was universally accepted as an undeniable fact, proved by hundreds of instances of extorted or voluntary confession, and supplemented by the concurrent testimony of a still greater number of witnesses who genuinely believed themselves to have been the spectators or victims of the supernatural powers of the accused.

Fig. 49. – Mantis (a very characteristic figure).

(From the ’Rh Ya.)

An historian of these later times might well have described such things as realities, and we should not be disposed, on account of his having done so, to question the validity of his description of other objects or creatures existing at the period, presuming them to be more consistent with our present notions of possibility.

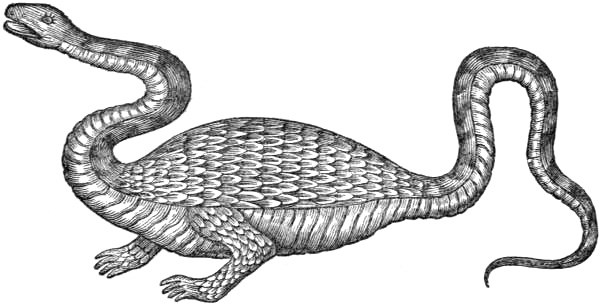

No one, now-a-days, would discredit the veracity of Marco Polo because he speaks of enormous serpents in Carajan, possessing two feet, each armed with a single claw. That there was a solid foundation for his story is admitted, and commentators are only at variance as to whether the basis was a large species of python, such as still exists in Southern China, or a gigantic alligator, of which he might have seen a mutilated specimen.

It must also be borne in mind that the existence of some gigantic saurian, now extinct, possessing two limbs only, in place of four, is not an impossibility; as the small lizard, Chirotes, is in that condition, and also the North American genus Siren, belonging to the Newts.

Fig. 50. – Tools of Husbandry. (From the ’Rh Ya.)

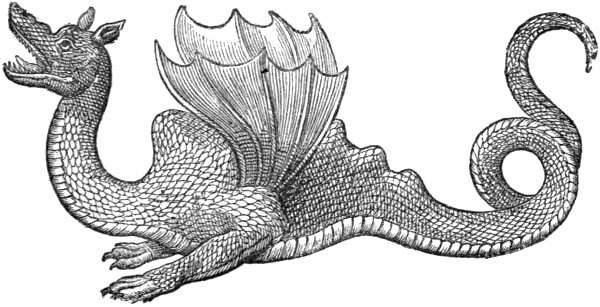

I notice that Retzoch, in his designs to illustrate Schiller’s poem, “The Fight with the Dragon,” makes the monster have only two fore-legs, and this appears to have been a common mediæval conception of it. Aldrovandus and Gesner both give figures of biped dragons. There is also a curious drawing in the Gentleman’s Magazine for 1749 – which is transferred into the pages of the Encyclopædia of Philadelphia, apparently a piracy of an English Cyclopædia, of what is styled a sea-dragon, four feet long, which stands bolt upright on two legs, and, like Barnum’s mermaid, was probably a triumph of art.

Fig. 51. – Draco bipes apteros captus in Agro Bononiensi. (Aldrovandus.)

Aldrovandus was probably imposed on by some waggish friend, in reference to the biped dragon without wings, two cubits long, which was said to have been killed by a countryman near Bonn in 1572 A.D., and which he first figured and then placed in his museum; and he evidently fully believed in the Ethiopian winged biped dragon, of which he gives two figures, but without quoting his authority.

Fig. 52. – Draco Æthiopicus. (Aldrovandus.)

Gesner gives a similar figure, after Belon, of the winged dragon of Mount Sinai; but Athanasius Kircher is more liberal, and gives his dragon not only wings but four legs.

Fig. 53. – The Four-footed Winged Dragon. (Kircher.)

In poetry we find Ashtaroth described as appearing to Faust in the form of a serpent with two little feet.

As to the mysterious powers imputed throughout the Shan Hai King to different creatures, of controlling drought, rain, and fire, or acting, when partaken of, as remedies for sundry ills and ailments, it may be asked whether we ourselves are free from analogous superstitious beliefs? Will a sailor view without uneasiness the destruction of a Mother Carey’s chicken, or a Dutchman, of a stork? Or is the Chinese pharmacopœia of the present day much more trustworthy as to many of its items?

As to the human-visaged creatures, both snakes and four-footed beasts, may we not perhaps put them on a par with other fancied resemblances, which hold to the present day, of (for example) the hippopotamus, to a river-horse, of the pipe-fish, known as the hippocampus, to a sea-horse; of the manatee to a merman, and the like?

And, lastly, are the composite creatures, partly bird and partly reptilian, occasionally referred to, so entirely incredible? Is it not barely possible that some of those intervening types which we know from the teaching of Darwin, must have existed; which we know, from the researches of palæontology have existed; types intermediate to the Struthionidæ, the most reptilian of birds, and the Chlamydæ, the most avian of reptiles – is it not possible that some of these may have continued their existence down to a late date, and that the tradition of these existing as the descendants or the analogues of the Archæopteryx, and the toothed birds of America, may be embalmed in the pages in question? Is it impossible? Do not the Trigonias, the Terebratulas, the Marsupials, and, in part, the vegetation of Australia, form the spare surviving descendants of the forms which characterised the oolitic period on our own shores? Why, then, may not a few cretaceous and early tertiary forms have struggled on, through a happy combination of circumstances, to an aged and late existence in other lands.

After long, repeated, and careful examination of the Shan Hai King, I arrive at a very different conclusion from M. Bazin. I hold it to be an authentic and precious memorial which has been handed down to us from remote antiquity, the value of which has been unrecognised owing to the book being unfortunately a fusion of two and perhaps three distinct works.

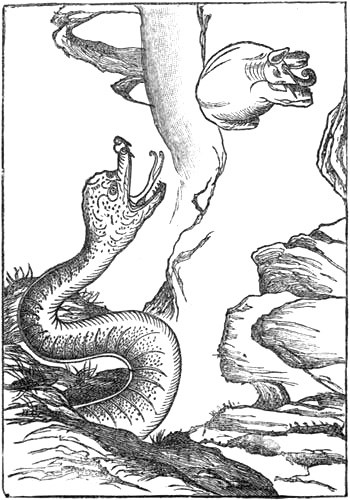

Fig. 54. – The Pa Snake. (From the Shan Hai King.)

The oldest was the Shan King, and consists of five volumes, devoted respectively to the northern, southern, eastern, western, and central mountain ranges. This is devoid of all reference to persons and habited places. It is simply an abstract of the results of a topographical survey which may not impossibly have been, as it claims, the one conducted by Yü.

It contains lists of mountains and rivers, with valuable notes on their mineral productions, fauna and flora. It also gives lists of the divinities controlling or belonging to each mountain range, and the sacrifices suitable to them. There are few extravagances in this portion of the work.

The remainder is devoted to a history of the regions without and within the four hai or seas bounding the empire, and those constituting what is called the Great Desert. Here extravagant stories, myths, accounts of wonderful people, references to states, cities, and tribes are mingled with geographical notices which, from their repetition, show that this portion is itself resolvable into two distinct works of more modern date, whose origin was probably posterior to the wave of Taouist superstition which swept over China in the first six centuries of our era. I must add that the term, “within the four seas” does not imply the arrogant belief, as is generally supposed, that this Empire extended to the ocean on every side, the archaic meaning being the very different one of frontier or boundary region; while the word “desert” has a similar signification.

In that more credible portion of the work which I believe to have been the original Shan King, references to dragons are infrequent. In some instances the kiao (which I interpret as the gavial) is specifically referred to; in others the word lung is used; thus, it speaks of dragons and turtles abounding in the Ti River, flowing from one of the northern mountains east of the Ho. From the context, however, an aquatic creature, and probably an alligator, is indicated. From the entire text I gather that the true terrestrial dragon was not an inmate of China, at all events after the period of Yü. I further infer that it was a feared and much respected denizen of the more or less arid highlands, whence the early Chinese either migrated or were driven, and from which point the dragon traditions flowed pretty evenly east and west, beat against the Himalayan chain on the south, and only penetrated India in a later and modified form.

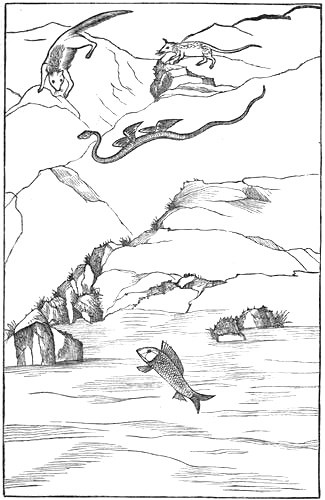

Fig. 55. – Flying Snakes from the SienMountains (Central Mountains).

(Shan Hai King.)

There is a short reference to the Ying Lung or winged dragon; it is as follows: —

“In the north-east corner of the Great Desert are mountains called Hiung-li and T’u K’iu. The Ying Lung lives at the south extremity.

“[Commentary. – The Ying Lung is a dragon with wings.]

“He killed Tsz Yiu and Kwa Fu.

“[Commentary. – Tsz Yiu was a soldier.]

“He could not ascend to heaven.

“[Commentary. – The Ying Lung dwells beneath the earth.]

“So there is often drought.

“[Commentary. – Because no rain was made above.]

“When there is a drought, the form of the Ying dragon is made, and then there is much rain.

“[Commentary. – Now the false dragon is for this purpose, to influence (the heaven); men are not able to do it.]”

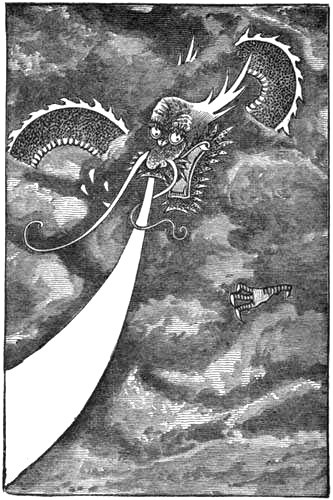

The better printed copies of this work are illustrated with a very truculent-looking dragon with outspread wings. A stone delineation of a dragon with wings forms the ornamentation of the bridge at Nincheang Foo. In the interior of China, it was observed by Mr. Cooper, and is given in his Travels of a Pioneer of Commerce. These are the only cases in China in which I have come across illustrations of dragons with genuine wings. As a rule, the dragon appears to be represented as having the power of translating itself without mechanical agency, sailing among the clouds, or rising from the sea at pleasure.

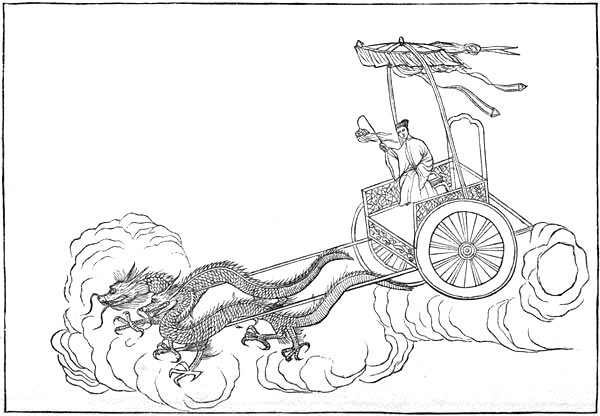

Fig. 56. – Ping I (Icy Exterminator), A River Divinity (?).

From within the Sea and North. (Shan Hai King.)

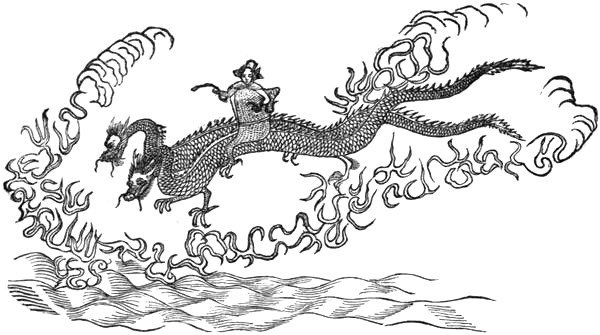

Fig. 57. – The Emperor K’i, of the Hia Dynasty.

From without the Sea and West. (Shan Hai King.)

The Shan Hai King contains valuable notices of winged snakes and gigantic serpents, as, for example, the so-called singing snakes. Speaking of the Sien mountain (one of the Central Mountains), it says: “Gold and jade abound. It is barren. The Sien river issues and flows north into the I river. On it are many singing snakes. They look like snakes, but have four wings. Their voice is like the beating of stones. When they appear there will be great drought in the city.”

Fig. 58. – Yü Kiang (a God). Without the Sea and North. (Shan Hai King.)

The Pa snake, already spoken of, is described as capable of gorging an elephant. The Ta Hien mountains were reputed uninhabitable on account of the presence of gigantic serpents (pythons?), which were said to have been of the colour of mugwort, to have possessed hairs like pig’s bristles projecting between the lines of their riband-like markings. Rumour had magnified their length to one hundred fathoms, and they made a noise like the beating of a drum or the striking of a watchman’s wooden clapper. The Siong Jan mountains were infested by serpents, also gigantic, but of a different species.

The annexed wood-cuts (Figs. 56, 57) of Ping I (Icy exterminator), and the Emperor K’i (B.C. 2197), each in cars, driving two dragons, are interesting in connection with the later fable of Medea and Triptolemus. The two stories were probably derived from a common source; the Chinese version, however, being much the older of the two.

Fig. 59. – The Typhoon Dragon.

(From a Chinese Painting.)

The text as to K’i is: – “K’i of the Hia dynasty danced with Kiutai at the Tayoh common. He drove two dragons. The clouds overhung in three layers. In his left hand he grasped a screen; in his right hand he held ear ornaments; at his girdle dangled jade crescents. It is north of Tayun mount; one author calls it Tai common.” The commentator says Kiutai is the name of a horse, and “dance” means to dance in a circle. [Probably this is the earliest reference extant to a circus performance.]

Ping I is supposed to dwell in Tsung Ki pool near the fairy region of Kwa-Sun, to have a human face, and to drive two dragons.

Cursorily examined, the Shan Hai King is a farrago of falsehood; read with intelligence, it is a mine of historical wealth.

The Pan Tsao Kang Mu.240Descending to late times, we have the great Chinese Materia Medica, in fifty-two volumes, entitled Păn Tsao Kang Mu, made up of extracts from upwards of eight hundred preceding authors, and including three volumes of illustrations by Li Shechin, of the Ming dynasty (probably born early in the sixteenth century A.D.). It was first printed in the Wăn-leih period (1573 to 1620). I give its article upon the dragon in extenso.

“According to the dictionary of Hü Shăn, the character lung in the antique form of writing represents the shape of the animal. According to the Shang Siao Lun, the dragon is deaf, hence its name of lung (deaf). In Western books the dragon is called nake (naga). Shi-Chăn says that in the ’Rh Ya Yih of Lo-Yuen the dragon is described as the largest of scaled animals (literally, insects). Wang Fu says that the dragon has nine (characteristics) resemblances. Its head is like a camel’s, its horns like a deer’s, its eyes like a hare’s,241 its ears like a bull’s, its neck like a snake’s, its belly like an iguanodon’s (?), its scales like a carp’s, its claws like an eagle’s, and its paws like a tiger’s. Its scales number eighty-one, being nine by nine, the extreme (odd or) lucky number. Its voice resembles the beating of a gong. On each side of its mouth are whiskers, under its chin is a bright pearl, under its throat the scales are reversed, on the top of its head is the poh shan, which others call the wooden foot-rule. A dragon without a foot-rule cannot ascend the skies. When its breath escapes it forms clouds, sometimes changing into rain, at other times into fire. Luh Tien in the P’i Ya remarks, when dragon-breath meets with damp it becomes bright, when it gets wet it goes on fire. It is extinguished by ordinary fire.

“The dragon comes from an egg, it being desirable to keep it folded up. When the male calls out there is a breeze above, when the female calls out there is a breeze below, in consequence of which there is conception. The Shih Tien states, when the dragons come together they are changed into two small serpents. In the Siao Shwoh it is said that the disposition of the dragon is very fierce, and it is fond of beautiful gems and jade (?). It is extremely fond of swallow’s flesh; it dreads iron, the mong plant, the centipede, the leaves of the Pride of India, and silk dyed of different (five) colours. A man, therefore, who eats swallow’s flesh should fear to cross the water. When rain is wanted a swallow should be offered (used); when floods are to be restrained, then iron; to stir up the dragon, the mong plant should be employed; to sacrifice to Küh Yuen, the leaves of the Pride of India bound with coloured silk should be used (see Mayers, p. 107, § 326) and thrown into the river. Physicians who use dragons’ bones ought to know the likes and dislikes of dragons as given above.”

“Dragons’ Bones.242– In the Pieh luh it is said that these are found in the watercourses in Tsin (Southern Shansi) and in the earth-holes which exist along the banks of the streams running in the caves of the T’ai Shan (Great Hill), Shantung. For seeking dead dragons’ graves there is no fixed time. Hung King says that now they are largely found in Leung-yih (in Shansi?) and Pa-chung (in Szchuen). Of all the bones, dragon’s spine is the best; the brains make the white earth striæ, which when applied to the tongue is of great virtue. The small teeth are hard, and of the usual appearance of teeth. The horns are hard and solid. All the dragons cast off their bodies without really dying. Han says the dragon-bones from Yea-cheu, Ts‘ang-cheu and T’ai-yuen (all in Shansi) are the best. The smaller bones marked with wider lines are the female dragon’s; the rougher bones with narrower lines are those of the male dragon; those which are marked with variegated colours are esteemed the best. Those that are either yellow or white are of medium value; the black are inferior. If any of the bones are impure, or are gathered by women, they should not be used.

“P’u says dragons’ bones of a light white colour possess great virtue. Kung says the bones found in Tsin (South Shansi) that are hard are not good; the variegated ones possess virtue. The light, the yellow, the flesh-coloured, the white, and the black, are efficacious in curing diseases in the internal organs having their respective colours, just as the five varieties of the chi243 plant, the five kinds of limestone, and the five kinds of mineral oil (literally, fat), which remain still for discussion in this work.