полная версия

полная версияMythical Monsters

Parallel instances of invasions of animals materially affecting the prosperity of man are doubtless familiar to my readers, such as the occasional migration of lemmings, passage of rats, flights of locusts, or the ravages caused by the Colorado beetle; but many are perhaps quite unaware what a terrible plague can be established, in the course of a very few years, by the prolific unchecked multiplication of even so harmless, innocent, and useful an animal as the common rabbit. The descendants of a few imported pairs have laid waste extensive districts of Australia and New Zealand, necessitated an enormous expenditure for their extirpation, and have at the present day189 caused such a widespread destruction of property in the latter country, that large areas of ground have actually had to be abandoned and entirely surrendered to them.

It is interesting to find in the work of the Arabic geographer El Edrisi a tradition of an island in the Atlantic, called Laca, off the north-west coast of Africa, having been formerly inhabited, but abandoned on account of the excessive multiplication of serpents on it. According to Scaligerus, the mountains dividing the kingdom of Narsinga from Malabar produce many wild beasts, among which may be enumerated winged dragons, who are able to destroy any one approaching their breath.

Megasthenes (tradente Æliano) relates that winged serpents are found in India; where it is stated that they are noxious, fly only by night, and that contact with their urine destroys portions of animals.

Ammianus Marcellinus (who wrote about the fourth century A.D.) states that the ibis is one among the countless varieties of the birds of Egypt, sacred, amiable, and valuable as storing up the eggs of serpents in his nest for food and so diminishing their number. He also refers to their encountering flocks of winged snakes, coming laden with poison from the marshes of Arabia, and overcoming them in the air, and devouring them before they quit their own region. And Strabo,190 in his geographical description of India, speaks of serpents of two cubits in length, with membraneous wings like bats: “They fly at night, and let fall drops of urine or sweat, which occasions the skins of persons who are not on their guard to putrefy.” Isaiah speaks of fiery flying serpents, the term “fiery” being otherwise rendered in the Alexandrine edition of the Septuagint by θανατοῦντες “deadly,” while the term “fiery” is explained by other authorities as referring to the burning sensation produced by the bite, and to the bright colour of the serpents.191 Collateral evidence of the belief in winged serpents is afforded by incidental allusions to them in the classics. Thus Virgil alludes to snakes with strident wings in the line

Illa autem attolit stridentis anguibus alis.192Lucan193 refers to the winged serpents of Arabia as forming one of the ingredients of an incantation broth brewed by a Thessalian witch, Erictho, with the object of resuscitating a corpse, and procuring replies to the queries of Sextus, son of Pompey. There are other passages in Ovid and other poets, in which the words “winged serpents” are made use of, but which I omit to render here, since from the context it seems doubtful whether they were not intended as poetic appellations of the monster to which, by popular consent, the term dragon has been generally restricted.

I feel bound to refer, although of course without attaching any very great weight of evidence to them, to the numerous stories popular in the East, in which flying serpents play a conspicuous part, the serpents always having something magical or supernatural in their nature. Such tales are found in the entrancing pages of the Arabian Nights, or in the very entertaining folk-lore of China, as given to us by Dr. N. P. Dennys of Singapore.194

The latest notice of the flying serpent that we find is in a work by P. Belon du Mans, published in 1557, entitled, Portraits de quelques animaux, poissons, serpents, herbes et arbres, hommes et femmes d’Arabie, Égypte, et Asie, observés par P. Belon du Mans. It contains a drawing of a biped winged dragon, with the notice “Portrait du serpent ailé” and the quatrain —

Dangereuse est du serpent la natureQu’on voit voler près le mont SinaiQui ne serait, de la voir, esbahy,Si on a peur, voyant sa pourtraiture?This is copied by Gesner, who repeats the story of its flying out of Arabia into Egypt.195 I attach considerable importance to the short extract which I shall give in a future page from the celebrated Chinese work on geography and natural history, the Shan Hai King, or Mountain and Sea Classic. The Shan Hai King claims to be of great antiquity, and, as Mr. Wylie remarks, though long looked on with distrust, has been investigated recently by scholars of great ability, who have come to the conclusion that it is at least as old as the Chow dynasty, and probably older. Now, as the Chow dynasty commenced in 1122 B.C., it is, if this latter supposition be correct, of a prior age to the works of Aristotle, Herodotus, and all the other authors we have been quoting, and therefore is the earliest work on natural history extant, and the description of the flying serpent of the Sien mountains (vide infrà) the earliest record of the existence of such creatures.

Classical Dragon and Mediæval DragonWhile the flying serpents of which we have just treated, will, if we assent to the reality of their former existence, assist greatly in the explanation of the belief in a winged dragon so far as Egypt, Arabia, and adjacent countries are concerned, it seems hardly probable that they are sufficient to account for the wide-spread belief in it. This we have already glanced at; but we now propose to examine it in greater detail, with reference to countries so distant from their habitat as to render it unlikely that their description had penetrated there.

The poets of Greece and Rome introduce the dragon into their fables, as an illustration, when the type of power and ferocity is sought for. Homer, in his description of the shield of Hercules, speaks of “The scaly horror of a dragon coiled full in the central field, unspeakable, with eyes oblique, retorted, that askant shot gleaming fire.” So Hesiod196 (750 to 700 B.C., Grote), describing the same object, says: “On its centre was the unspeakable terror of a dragon glancing backward with eyes gleaming with fire. His mouth, too, was filled with teeth running in a white line, dread and unapproachable; and above his terrible forehead, dread strife was hovering, as he raises the battle rout. On it likewise were heads of terrible serpents, unspeakable, twelve in number, who were wont to scare the race of men on earth, whosoever chanced to wage war against the son of Jove.”

Here it is noteworthy that Hesiod distinguishes between the dragon and serpents.

Ovid197 locates the dragon slain by Cadmus in Bœotia, near the river Cephisus. He speaks of it as being hid in a cavern, adorned with crests, and of a golden colour. He, like the other poets, makes special reference to the eyes sparkling with fire, and it may be noted that a similar brilliancy is mentioned by those who have observed pythons in their native condition. He speaks of the dragon as blue,198 and terribly destructive owing to the possession of a sting, long constricting folds, and venomous breath.

The story of Ceres flying to heaven in a chariot drawn by two dragons, and of her subsequently lending it to Triptolemus, to enable him to travel all over the earth and distribute corn to its inhabitants, is detailed or alluded to by numerous poets, as well as the tale of Medea flying from Jason in a chariot drawn by winged dragons. Ceres199 is further made to skim the waves of the ocean, much after the fashion of mythical personages depicted in the wood-cuts illustrating passages in the Shan Hai King.200 Ammianus Marcellinus, whose history ends with the death of Valerius in A.D. 378, refers, as a remarkable instance of credulity, to a vulgar rumour that the chariot of Triptolemus was still extant, and had enabled Julian, who had rendered himself formidable both by sea and land, to pass over the walls of, and enter into the city of Heraclea. Though rational explanations are afforded by the theory of Bochart and Le Clerc, that the story is based upon the equivocal meaning of a Phœnician word, signifying either a winged dragon or a ship fastened with iron nails or bolts; or by that of Philodorus, as cited by Eusebius, who says that his ship was called a flying dragon, from its carrying the figure of a dragon on its prow; yet either simply transposes into another phase the current belief in a dragon, without prejudicing it.

Diodorus Siculus disposes of the Colchian dragon and the golden-fleeced ram in a very summary manner, as follows: —

“It is said that Phryxus, the son of Athamas and Nephele, in order to escape the snares of his stepmother, fled from Greece with his half-sister Hellen, and that whilst they were being carried, under the advice of the gods, by the ram with a golden fleece out of Europe into Asia, the girl accidentally fell off into the sea, which on that account has been called Hellespont. Phryxus, however, being carried safely into Colchis, sacrificed the ram by the order of an oracle, and hung up its skin in a shrine dedicated to Mars.

“After this the king learnt from an oracle that he would meet his death when strangers, arriving there by ship, should have carried off the golden fleece. On this account, as well as from innate cruelty, the man was induced to offer sacrifice with the slaughter of his guests; in order that, the report of such an atrocity being spread everywhere, no one might dare to set foot within his dominions. He also surrounded the temple with a wall, and placed there a strong guard of Taurian soldiery; which gave rise to a prodigious fiction among the Greeks, for it was reported by them that bulls, breathing fire from their nostrils, kept watch over the shrine, and that a dragon guarded the skin, for by ambiguity the name of the Taurians was twisted into that of bulls, and the slaughter of guests furnished the fiction of the expiation of fire. In like manner they translated the name of the prefect Draco, to whom the custody of the temple had been assigned, into that of the monstrous and horrible creature of the poets.”

Nor do others fail to give a similar explanation of the fable of Phryxus, for they say that Phryxus was conveyed in a ship which bore on its prow the image of a ram, and that Hellen, who was leaning over the side under the misery of sea-sickness, tumbled into the water.

Among other subjects of poetry are the dragon which guarded the golden apples of the Hesperides, and the two which licked the eyes of Plutus at the temple of Æsculapius with such happy effect that he began to see.

Philostratus201 separates dragons into Mountain dragons and Marsh dragons. The former had a moderate crest, which increased as they grew older, when a beard of saffron colour was appended to their chins; the marsh dragons had no crests. He speaks of their attaining a size so enormous that they easily killed elephants. Ælian describes their length as being from thirty or forty to a hundred cubits; and Posidonius mentions one, a hundred and forty feet long, that haunted the neighbourhood of Damascus; and another, whose lair was at Macra, near Jordan, was an acre in length, and of such bulk that two men on horseback, with the monster between them, could not see each other.

Ignatius states that there was in the library of Constantinople the intestine of a dragon one hundred and twenty feet long, on which were written the Iliad and Odyssey in letters of gold. There is no ambiguity in Lucan’s202 description of the Æthiopian dragon: “You also, the dragon, shining with golden brightness, who crawl in all (other) lands as innoxious divinities, scorching Africa render deadly with wings; you move the air on high, and following whole herds, you burst asunder vast bulls, embracing them with your folds. Nor is the elephant safe through his size; everything you devote to death, and no need have you of venom for a deadly fate.” Whereas the dragon referred to by Pliny (vide ante, p. 169), as also combating the elephant, is evidently without wings, and may either have been a very gigantic serpent, or a lacertian corresponding to the Chinese idea of the dragon.

Descending to later periods, we learn from Marcellinus203 that in his day dragon standards were among the chief insignia of the Roman army; for, speaking of the triumphal entry of Constantine into Rome after his triumph over Magnentius, he mentions that numbers of the chief officers who preceded him were surrounded by dragons embroidered on various points of tissue, fastened to the golden or jewelled points of spears; the mouths of the dragons being open so as to catch the wind, which made them hiss as though they were inflamed with anger, while the coils of their tails were also contrived to be agitated by the breeze. And again he speaks of Silvanus204 tearing the purple silk from the insignia of the dragons and standards, and so assuming the title of Emperor.

Several nations, as the Persians, Parthians, Scythians, &c., bore dragons on their standards: whence the standards themselves were called dracones or dragons.

It is probable that the Romans borrowed this custom from the Parthians, or, as Casaubon has it, from the Dacae, or Codin, from the Assyrians; but while the Roman dracones were, as we learn from Ammianus Marcellinus, figures of dragons painted in red on their flags, among the Persians and Parthians they were, like the Roman eagles, figures in relievo, so that the Romans were frequently deceived and took them for real dragons.

The dragon plays an important part in Celtic mythology. Among the Celts, as with the Romans, it was the national standard.

While Cymri’s dragon, from the Roman’s holdSpread with calm wing o’er Carduel’s domes of gold.205The fables of Merllin, Nennius, and Geoffry describe it as red in colour, and so differing from the Saxon dragon which was white. The hero Arthur carried a dragon on his helm, and the tradition of it is moulded into imperishable form in the Faerie Queen. A dragon infested Lludd’s dominion, and made every heath in England resound with shrieks on each May-day eve. A dragon of vast size and pestiferous breath lay hidden in a cavern in Wales, and destroyed two districts with its venom, before the holy St. Samson seized and threw it into the sea.

In Celtic chivalry, the word dragon came to be used for chief, a Pendragon being a sort of dictator created in times of danger; and as the knights who slew a chief in battle were said to slay a dragon, this doubtless helped to keep alive the popular tradition regarding the monster which had been carried with them westward in their migration from the common Aryan centre.

The Teutonic tribes who invaded and settled in England bore the effigies of dragons on their shields and banners, and these were also depicted on the ensigns of various German tribes.206 We also find that Thor himself was a slayer of dragons,207 and both Siegfried and Beowulf were similarly engaged in the Niebelungen-lied and the epic bearing the name of the latter.208 The Berserkers not only named their boats after the dragon, but also had the prow ornamented with a dragon figure-head; a fashion which obtains to the present day among the Chinese, who have an annual dragon-boat festival, in which long snaky boats with a ferocious dragon prow run races for prizes, and paddle in processions.

So deeply associated was the dragon with the popular legends, that we find stories of encounters with it passing down into the literature of the Middle Ages; and, like the heroes of old, the Christian saints won their principal renown by dragon achievements. Thus among the dragon-slayers209 we find that —

1. St. Phillip the Apostle destroyed a huge dragon at Hierapolis in Phrygia.

2. St. Martha killed the terrible dragon called Tarasque at Aix (la Chapelle).

3. St. Florent killed a similar dragon which haunted the Loire.

4. St. Cado, St. Maudet, and St. Paul did similar feats in Brittany.

5. St. Keyne of Cornwall slew a dragon.

6. St. Michael, St. George, St. Margaret, Pope Sylvester, St. Samson, Archbishop of Dol, Donatus (fourth century), St. Clement of Metz, killed dragons.

7. St. Romain of Rouen destroyed the huge dragon called La Gargouille, which ravaged the Seine.

Moreover, the fossil remains of animals discovered from time to time, and now relegated to their true position in the zoological series, were supposed to be the genuine remains of either dragons or giants, according to the bent of the mind of the individual who stumbled on them: much as in the present day large fossil bones of extinct animals of all kinds are in China ascribed to dragons, and form an important item in the Chinese pharmacopœia. (Vide extract on Dragon bones from the Pen-tsaou-kang-mu, given on pp. 244-246.)

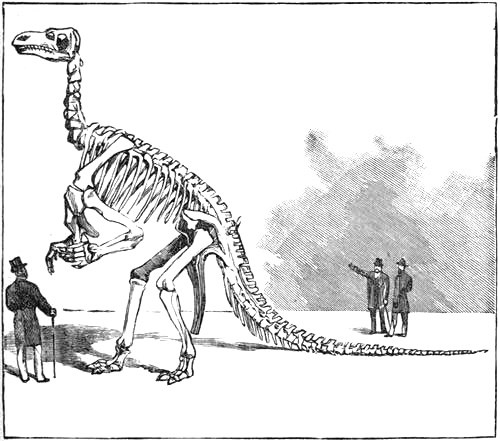

Fig. 38. – Skeleton of an Iguanodon.

The annexed wood-cut of the skeleton of an Iguanodon, found in a coal-mine at Bernissant, exactly illustrates the semi-erect position which the dragon of fable is reported to have assumed.

Among the latest surviving beliefs of this nature may be cited the dragon of Wantley (Wharncliffe, Yorkshire), who was slain by More of More Hall. He procured a suit of armour studded with spikes, and, proceeding to the well where the dragon had his lair, kicked him in the mouth, where alone he was vulnerable. The Lambton worm is another instance.

The explanations of these legends attempted by mythologists, based on the supposition that the dragons which are their subjects are simply symbolic of natural phenomena, are ingenious, and perhaps in many instances sufficient, but do not affect, as I have before remarked, the primitive and conserved belief in their previous existence as a reality.

Thus, the author of British Goblins suggests that for the prototype of the red dragon, which haunted caverns and guarded treasures in Wales, we must look in the lightning caverns of old Aryan fable, and deduces the fire-darting dragons of modern lore from the shining hammer of Thor, and the lightning spear of Odin.

The stories of ladies guarded by dragons are explained on the supposition210 that the ladies were kept in the secured part of the feudal castles, round which the walls wound, and that an adventurer had to scale the walls to gain access to the ladies; when there were two walls, the authors of romance said that the assaulter overcame two dragons, and so on. St. Romain, when he delivered the city of Rouen from a dragon which lived in the river Seine, simply protected the city from an overflow, just as Apollo (the sun) is symbolically said to have destroyed the serpent Python, or, in other words, dried up an overflow. And the dragon of Wantley is supposed by Dr. Percy to have been an overgrown rascally attorney, who cheated some children of their estates, but was compelled to disgorge by a gentleman named More, who went against him armed with the “spikes of the law,” whereupon the attorney died of vexation.

Furthermore, our dragoons were so denominated because they were armed with dragons, that is, with short muskets, which spouted fire like dragons, and had the head of a dragon wrought upon their muzzle.

This fanciful device occurs also among the Chinese, for a Jesuit, who accompanied the Emperor of China on a journey into Western Tartary in 1683, says, “This was the reason of his coming into their country with so great an army, and such vast military preparations; he having commanded several pieces of cannon to be brought, in order for them to be discharged from time to time in the valleys; purposely that the noise and fire, issuing from the mouths of the dragons, with which they were adorned, might spread terror around.”

Though dragons have completely dropped out of all modern works on natural history, they were still retained and regarded as quite orthodox until a little before the time of Cuvier; specimens, doubtless fabricated like the ingeniously constructed mermaid of Mr. Barnum, were exhibited in the museums; and voyagers occasionally brought back, as authentic stories of their existence, fables which had percolated through time and nations until they had found a home in people so remote from their starting point as to cause a complete obliteration of their passage and origin.

For instance, Pigafetta, in a report of the kingdom of Congo,211 “gathered out of the discourses of Mr. E. Lopes, a Portuguese,” speaking of the province of Bemba, which he defines as “on the sea coast from the river Ambrize, until the river Coanza towards the south,” says of serpents, “There are also certain other creatures which, being as big as rams, have wings like dragons, with long tails, and long chaps, and divers rows of teeth, and feed upon raw flesh. Their colour is blue and green, their skin painted like scales, and they have two feet but no more.212 The Pagan negroes used to worship them as gods, and at this day you may see divers of them that are kept for a marvel. And because they are very rare, the chief lords there curiously preserve them, and suffer the people to worship them, which tendeth greatly to their profits by reason of the gifts and oblations which the people offer unto them.”

And John Barbot, Agent-General of the Royal Company of Africa, in his description of the coasts of South Guinea,213 says: “Some blacks assuring me that they (i. e. snakes) were thirty feet long. They also told me there are winged serpents or dragons having a forked tail and a prodigious wide mouth, full of sharp teeth, extremely mischievous to mankind, and more particularly to small children. If we may credit this account of the blacks, they are of the same sort of winged serpents which some authors tell us are to be found in Abyssinia, being very great enemies to the elephants. Some such serpents have been seen about the river Senegal, and they are adorned and worshipped as snakes are at Wida or Fida, that is, in a most religious manner.”

Ulysses Aldrovandus,214 who published a large folio volume on serpents and dragons, entirely believed in the existence of the latter, and gives two wood engravings of a specimen which he professes to have received in the year 1551, of a true dried Æthiopian dragon.

He describes it as having two feet armed with claws, and two ears, with five prominent and conspicuous tubercles on the back. The whole was ornamented with green and dusky scales. Above, it bore wings fit for flight, and had a long and flexible tail, coloured with yellowish scales, such as shone on the belly and throat. The mouth was provided with sharp teeth, the inferior part of the head, towards the ears, was even, the pupil of the eye black, with a tawny surrounding, and the nostrils were two in number, and open.

He criticises Ammianus Marcellinus for his disbelief in winged dragons, and states in further justification of his censure that he had heard, from men worthy of confidence, that in that portion of Pistorian territory called Cotone, a great dragon was seen whose wings were interwoven with sinews a cubit in length, and were of considerable width; this beast also possessed two short feet provided with claws like those of an eagle. The whole animal was covered with scales. The gaping mouth was furnished with big teeth, it had ears, and was as big as a hairy bear. Aldrovandus sustains his argument by quotations from the classics and reference to more recent authors. He quotes Isidorus as stating that the winged Arabian serpents were called Sirens, while their venom was so effective that their bite was attended by death rather than pain; this confirms the account of Solinus.

He instances Gesner as saying that, in 1543, he understood that a kind of dragon appeared near Styria, within the confines of Germany, which had feet like lizards, and wings after the fashion of a bat, with an incurable bite, and says these statements are confirmed by Froschonerus in his work on Styria (idque Froschonerus ex Bibliophila Stirio narrabat). He classes dragons (which he considers as essentially winged animals) either as footless or possessing two or four feet.

He refers to a description by Scaliger215 of a species of serpent four feet long, and as thick as a man’s arm, with cartilaginous wings pendent from the sides. He also mentions an account by Brodeus, of a winged dragon which was brought to Francis, the invincible King of the Gauls, by a countryman who had killed it with a mattock near Sanctones, and which was stated to have been seen by many men of approved reputation, who thought it had migrated from transmarine regions by the assistance of the wind.