полная версия

полная версияThe Operatic Problem

Works of foreign composers produced at the opera, do not count in the number of acts stipulated by the cahier de charges, the respective paragraphs being drawn up in favour of native composers; nor can any excess in the number of acts produced in one year be carried over to the next year.

Amongst the prerogatives of the Paris opera director, is the absolute monopoly of his repertory in the capital – works in the public domain excepted – and the right to claim for his theatre the services of those who gain the first prizes at the final examinations of the operatic classes at the Conservatoire.

Towards the working expenses of his theatre the director has, firstly, the subvention and the subscription, and, secondly, the alea of the box-office sales. The subvention of 800,000 francs divided by the number of obligatory performances gives close upon £170 towards each, and the subscription averages £400 a night, or £570 as a minimum with which the curtain is raised, and it is the manager's business to see that his expenses do not exceed the sum. The "house full" receipts being very little over £800 at usual prices, the margin is not very suggestive of huge profits. Indeed, with the constantly rising pretensions of star artists, spoilt by the English, and American markets, and the fastidious tastes of his patrons, the Paris opera director has some difficulty in making both ends meet. Within the last fifteen years the two Exhibition seasons have saved the management from financial disaster, and this only by performing every day, Sundays sometimes included. Some fifty new works by native composers have been produced at the opera since the opening of the new house in 1876, and six by foreign composers —Aida, Otello, Lohengrin, Tannhäuser, Walküre, and Meistersinger. The maximum of performances falls to Romeo et Juliette, this opera heading also the figure of average receipts with 17,674 francs (about £507). Eleven works have had the misfortune to figure only between three and nine times on the bill.

Independently of the supervision exercised by the Minister of Fine Arts, the strictest watch is kept over managerial doings by the Société des Auteurs, a legally constituted body which represents the authors' rights, and is alone empowered to treat in their names with theatrical managers, to collect the fees, to guard the execution of contracts and even to impose fines.

Thus is national art in France not only subsidised and patronised, but safeguarded and protected.

The English National Opera House

Three factors determine the existence of any given theatre and have to be considered with reference to my proposed National Opera House, namely, tradition, custom, and enterprise.

I have proved we possess an operatic tradition, and as regards custom no one will dispute the prevalence of a taste for opera. Indeed, from personal experience, extending over a number of years, I can vouch for a feeling akin to yearning in the great masses of the music-loving public after operatic music, even when stripped of theatrical paraphernalia, such, for example, as one gets at purely orchestral concerts. It is sufficient to follow the Queen's Hall Wagner concerts to be convinced that the flattering patronage they command is as much a tribute to the remarkably artistic performance of Mr Henry Wood, as it is due to the economy of his programmes. Again, in the provinces, I have observed, times out of number, crowded audiences listening with evident delight, not only to popular operas excellently done by the Moody-Manners' Company, but to performances of Tristan and Siegfried, which, for obvious reasons, could not give the listeners an adequate idea of the real grandeur of these works. But the love of opera is there, and so deeply rooted, that, rather than be without it, people are willing to accept what they can get.

This much, then, for tradition and custom.

As regards enterprise in the operatic field, it can be twofold – either the result of private initiative, working its own ends independently, or else it is organised, guided, and helped, officially.

It is under the former aspect that we have known it, so far, in this country, and as we are acquainted with it, especially in London, we find it wanting, from the point of view of our special purpose. Not that it should be so, for the Covent Garden management, as at present organised, could prove an ideal combination for the furtherance of national art, were its aims in accordance with universal, and, oft-expressed, desire. What better can be imagined than a theatre conducted by a gathering representative of, nobility, fashion, and wealth?

It is under such auspices that opera originated, and that native art sprang to life and prospered everywhere; and it is to these one has the right to turn, with hope and trust, in England. But when wealth and fashion stoop from the pedestal assigned to them by tradition, and barter the honoured part of Mæcenas for that of a dealer, they lose the right to be considered as factors in an art problem, and their enterprise may be dismissed from our attention. For the aim of an opera house, worthy of a great country like England, should not be to make most money with any agglomeration of performers, and makeshift mise-en-scène, but to uphold a high standard of Art.

But the elimination of private enterprise from my scheme is but one more argument in favour of official intervention, and the experience of others will stand us in good stead.

Of the three systems of State subsidised theatres, as set out in my exposé of operatic systems in Italy, Germany, and France, the ideal one is, of course, the German, where the Sovereign's Privy Purse guarantees the working of Court theatres, and secures the future of respective personnels. But the adoption of this plan, or the wholesale appropriation of any one other, cannot be advocated, if only because the inherent trait of all our institutions is that they are not imported, but the natural outcome of historical, or social, circumstances. My purpose will be served as well, if I select the salient features of each system.

Thus, in the first instance, admitting the principle of State control in operatic matters, I will make the furtherance of national art a condition sine qua non of the very existence of a subsidised theatre, and performances in the English language obligatory.

Secondly, I will adopt the German system of prevoyance, in organising old age pensions for theatrical personnels.

Thirdly, I will borrow from Italy the idea of municipal intervention, all the more as the municipal element has become, of late, an all-important factor in the economy of our civic life, and seems all but indicated to take active part in a fresh phase of that life.

I do not see how any objection can be raised to the principle of these three points, though I am fully aware of the difficulties in the way of each; difficulties mostly born of the diffidence in comparing the status of operatic art abroad, with its actual state in this country. It must be borne in mind, however, that I am endeavouring to give help to the creation of a national art, and not promoting a plan of competition with the operatic inheritance of countries which have had such help for over two centuries.

We are making a beginning, and we must perforce begin ab ovo, doing everything that has been left undone, and undoing, at times, some things that have been, and are being, done. Let me say, at once, to avoid misapprehension, that I refer here to the majority of the Anglicised versions of foreign libretti. They are unsatisfactory, to put it very mildly, and, will have to be re-written again before, these operas can be sung with artistic decency in English. The classes of our great musical institutions will have to be reorganised entirely, from the curriculum of education to examinations. This is a crude statement of the case, the details can always be elaborated on the model of that fine nursery of artists, the Paris Conservatoire. We must not be deterred by the possible scarcity of native professors, able to impart the indispensable knowledge. Do not let us forget that the initial instructors of operatic art came from Italy to France, together with the introduction of their new art; but, far from monopolising tuition, they formed pupils of native elements, and these in turn became instructors, interpreters, or creators. The same thing will happen again, if necessary, let us by all means import ballet masters, professors of deportment, singing teachers, and whoever can teach us what we do not know, and cannot be taught by our own men. Pupils will be formed soon enough, and the foreign element gradually eliminated. Do not let us forget, either, that stalest of commonplaces that "Rome was not built in a day."

We are not trying to improvise genii, or make a complete art, by wishing for the thing, but we are laying foundations for a future architecture, every detail of which will be due to native enterprise, and the whole a national pride. To look for immediate results would be as idle as to expect Wagners, and Verdis, or Jean de Reszkes, and Terninas, turned out every year from our schools, simply because we have a subsidised opera house, and reorganised musical classes.

We are bound to arrive at results, and no one can say how great they may be, or how soon they may be arrived at. The unexpected so often happens. Not so many years ago, for example, operatic creative genius seemed extinct in the land of its birth, and the all-pervading wave of Wagnerism threatened the very existence of musical Italy, when, lo! there came the surprise of Cavalleria Rusticana, and the still greater surprise of the enthusiasm with which the work was received in Germany, and the no less astonishing rise of a new operatic school in Italy, and its triumphant progress throughout the musical world. Who can say what impulse native creative talent will receive in this country, when it is cared for as it certainly deserves?

The question arises now of the most practical manner in which this care can be exercised?

Plans have been put forward more than once, – discussed, and discarded. This means little. Any child can pick a plan to pieces, and prove its unworthiness. Goodwill means everything, and a firm conviction that in the performance of certain acts the community does its duty for reasons of public welfare. I put more trust in these than in the actual merit of my scheme, but, such as it is, I submit it for consideration, which, I hope, will be as seriously sincere, as the spirit in which it is courted.

I would suggest that the interests of the National Opera House in London, should be looked after by a Board under the supervision of the Education Department, the members of the Board being selected from among the County Councillors, the Department itself, and some musicians of acknowledged authority.

The enlisting of the interest of the Educational Department would sanction the theory of the educational mission of the venture; the County Council comes into the scheme, for financial and administrative purposes; the selection of musicians needs no explanation, but a proviso should be made that the gentlemen chosen, have no personal interest at stake.

As I said before, we have to begin at the beginning, and so the duties of the Board would be: —

1. The building of a National Opera House in London.

2. The drawing up of a schedule of stipulations on the lines of the French cahier des charges regulating the work of the theatre.

3. The appointment of a manager.

4. The supervision of the execution of the stipulations embodied in the schedule.

5. The provision of funds for the subsidy.

As to the first of these points, I do not at all agree with those who wish every new opera house constructed in servile imitation of the Bayreuth model. Such a theatre would only be available for operatic performances of a special kind, but the structure of the auditorium would result in the uniformity of prices which goes dead against the principle of a theatre meant for the masses as well as for the classes.

All that I need say here is, that our National Opera House should be built in London, and according to the newest inventions, appliances and most modern requirements.

As regards the second point, enough has been said about describing foreign systems to show how a schedule of stipulations should be drawn up, when the time comes.

Concerning the appointment of a manager, it goes without saying that the director of our National Opera House must be an Englishman born and bred, and a man of unimpeachable commercial integrity and acknowledged theatrical experience. Such a selection will make the task of the Board in supervising the work an extremely easy one.

The provision of funds is the crucial point of the scheme. Before going into details, let me appeal to the memory of the British public once more, praying that it will remember that every year some £50,000 or £60,000 of national cash is spent in ten or twelve weeks to subsidise French, German and Italian artistes in London. It is but reasonable to suppose that if an authoritative appeal for funds on behalf of National Opera were made, at least half of this money would be forthcoming for the purpose. And so I would advocate such an appeal as the first step towards solving the financial problem of my scheme. Secondly, there would have to be a first Parliamentary grant and an initial disbursement of the County Council funds, all towards the building of the opera house. It is impossible to name the necessary sum; but one can either proceed with what one will eventually have, or regulate expenditure according to estimates.

The house once built and the manager appointed, both Parliamentary and County Council grants will have to be renewed every year, the sum-total being apportioned to the probable expenses of every performance, the number of performances and the length of the operatic season. The best plan to follow here would be to have a season of, say nine or ten months, with four performances a week.

The manager would receive the house rent free, but should on his side show a working capital representing at least half the figure of the annual subsidy, and, further, lodge with the Board a deposit against emergencies. Considering the initial expenses of the first management, when everything, from insignificant "props" to great sets of scenery will have to be furnished in considerable quantities, there should be no charges on the manager's profits in the beginning, for a year or two. But later on, 10 per cent. off the gross receipts of every performance might be collected, one part of the proceeds going towards a sinking fund to defray the cost of the construction of the house, and the other towards the establishment of a fund for old age pensions for the personnel of the opera house.

A further source of income that would go towards indemnifying the official outlay might be found in a toll levied on the purchaser of 2d. in every 10s. on all tickets from 10s. upwards, of 1d. on tickets between 5s. and 10s., and of ½d. on all tickets below 5s. I would make also compulsory a uniform charge of 6d. for every complimentary ticket given away.

It is well-nigh impossible in the present state of my scheme to go into details of figures, especially concerning the official expenditure. But, as figures have their eloquence, we may venture on a forecast of such returns as might be reasonably expected to meet the outlay. I take it for granted that our opera house will be built of sufficient dimensions to accommodate an audience of 3000, and arranged to make an average of £700 gross receipts (subvention included) per performance possible. Taking the number of performances in an operatic season at 160 to 180, four performances a week in a season of nine or ten months, we get a total of receipts from £112,000 to £126,000, or, £11,200 to £12,600, repaid yearly for the initial expenses of the subsidising bodies, as per my suggestion of 10 per cent. taken off the gross receipts. The toll levied on tickets sold should average from £1446, 13s. 4d. to £1650 annually, with an average audience of 750 in each class of toll for each performance: altogether between £12,646 and £14,250 of grand total of returns. From a purely financial point of view, these might be considered poor returns for an expenditure in which items easily figure by tens of thousands. But, in the first instance, I am not advocating a speculation, and secondly, there are other returns inherent to my venture, one and all affecting the well-being of the community more surely than a lucrative investment of public funds. The existence of a National Opera House gives, first of all, permanent employment to a number of people engaged therein, and which may be put down roughly at 800 between the performing and non-performing personnel. Such is, at least, the figure at all great continental opera houses.

In Vienna, the performing personnel, including chorus, orchestra, band, ballet, supers and the principal singers, numbers close upon 400. Then follows the body of various instructors, regisseurs, stage managers, repetiteurs, accompanists, etc., then come all the stage hands, carpenters, scene-shifters, machinists, electricians, scenographers, modellers, wig-makers, costumiers, property men, dressers, etc., etc., etc., and on the other side of the footlights there are ushers, ticket collectors, and the whole of the administration. Thus one single institution provides 800 people not only with permanent employment but with old age pensions. Nor is this all. The proper working of a large opera house necessitates a great deal of extraneous aid and calls to life a whole microcosm of workers, trader manufacturers and industries of all kinds.

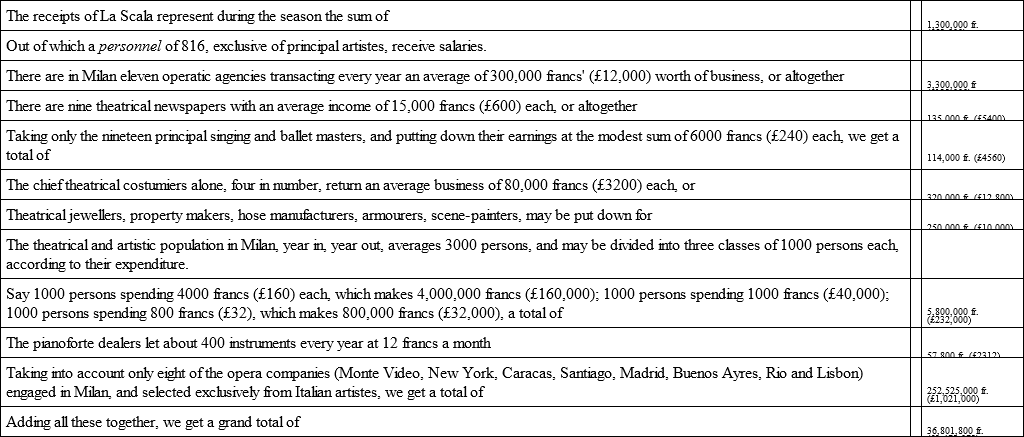

Let us take here the statistics for the city of Milan to better grasp my meaning. The figures are official, and are taken from a report presented to the municipality some time ago, and prove there is a business side of vital importance attached to the proper working of the local subsidised theatre, La Scala. The following are the items of what they call giro d'affari, or, in paraphrase, of "the operatic turn-over," and all are official figures.

Very nearly a million and a half sterling turned over in operatic, business in one city. And there are scores of minor items, all sources of profit, that have to be neglected. But I must point out that no less than 1745 families derive employment and a regular income from the theatrical industry of Milan. It is quite true that the capital of Lombardy enjoys a position which is unique not only in Italy but in the whole world, as the chief operatic market, and there is nothing that indicates this artistic centre is likely to be shifted, much less to London than anywhere else. But it would be interesting to know how much English money goes towards the fine total of the Milanese operatic turn-over. There is no reason why we should not have our twenty odd trades, as in Milan, and at least 1745 households whose material existence would be definitely secured through their association with a National Opera House. If I am not writing in vain, our results should be infinitely greater, differing from continental ones as a franc or a mark differs from a pound sterling. And should the great provincial towns follow the lead of London, entrusting their municipalities with the creation and organisation of opera houses, if Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Leeds, Glasgow, Sheffield, Bradford, Dublin, Hull, Southampton, Plymouth, Wolverhampton, etc., will turn a part of their wealth towards promoting a scheme of the greatest importance to the art of the nation; if all that goes to foreign pockets for foreign art is used for patriotic purposes – then England will be able to show an operatic turn-over worthy of her supremacy in other spheres. For every Italian household living on opera we will have ten, and prosperity will reign where, so far, art and an artistic education have brought only bitter disappointment. I am writing of "Music as a profession" in England. The multiplication of our music schools seems to be accepted as a great matter of congratulation, and we are perpetually hearing the big drum beaten over the increasing number of students to whom a thorough musical education has been given; but who asks what becomes of them all? Oft-met advertisements offering music lessons at 6d. an hour are perhaps an answer. It would be profitless to pursue this topic, but all will agree that it is far better to sing in an operatic chorus at 30s. or £2 per week than be one of the items in a panorama of vanished illusions and struggling poverty, the true spectacle of the singing world in London.

The establishment of National Opera in England, putting artistic considerations aside, presents the following material and commercial advantages, viz., provision of permanent employment for artisans, mechanics, workmen and manual labourers; an impulse to various special industries, some developed, some improved, others created; an honourable occupation to hundreds kept out, so far, from an exclusive and over-crowded profession, and a provision for old age. In other words, the solution of the operatic problem in England might prove a step towards the solution of a part of the social problem.

That my scheme for the establishment of an English National Opera House is perfect, I do not claim for a moment. That my plans might be qualified as visionary and my hope of seeing a national art called to life through the means I advocate considered an idle dream is not unlikely.

But my conviction in the matter is sincere, and I can meet the sceptics with the words of the old heraldic motto which apologises for the fiction of a fabulous origin of a princely house: etiamsi fabula, nobilis est.

OPERA FOR THE PEOPLE

Opera for the PeopleThe ceremony of opening a new organ, the gift of Mrs Galloway, was performed by Mr W. Johnson Galloway, M.P., in the City Road Mission Hall, Manchester, on Friday evening, September 6, in the presence of a crowded gathering. A Recital was given by Mr David Clegg. Mr Galloway, M.P., who took the chair, in opening the proceedings, said: – On an occasion such as this, it will not, I am sure, be deemed superfluous if I take a brief bird's-eye view of the history of music, and in a – comparatively speaking – few sentences trace its progress towards the position it now holds among the arts of modern life. Music, in one form at least, has been with us since the creation of man, for we may reasonably believe that in his most elementary stage, he discovered some vocal phrases which gave him a certain rude pleasure to repeat, or chant, in association with his fellows. Travellers, who have penetrated the confines of remote and savage countries, have told us of the curious chanting of their inhabitants when engaged in what, to them, were their religious and festal celebrations; and as we cannot conceive man in a more primitive condition, we may take it, that in prehistoric times there was a limited melodic form, which afforded that peculiar delight to the savage mind, that the glorious polyphonic combination of to-day, give to the cultured races of Eastern and Western civilisation. Our slight knowledge of the art, in its early state we owe to such records, as have been handed down to us from that which may be termed the golden era of civilisation in Egypt. Long before the sway of the Ptolemies – ages before Cleopatra took captive her Roman Conqueror – music formed not only an indispensable part in religious and State functions, but entered largely into the social life of the people, and of this there is indisputable evidence in the hieroglyphics and carvings, to be found on the seemingly imperishable monuments, which the researches of archæologists have revealed to the knowledge of man. Of ancient Hebrew music we do not know much, but we may assume, that during the Captivity they learned not a little from their Egyptian masters, although it does not appear – judging from the harsher and more blatant character of their instruments – that they attained the degree of refinement achieved by the Egyptians. It would seem, from the many allusions contained in the Bible, that the Jews were more particularly attracted towards the vocal, rather than the instrumental, side of the art. Many a familiar biblical phrase will probably crop up in our mind. The psalms that are sung during Divine Service teem with such references. "O sing unto the Lord a new song," "How shall we sing the Lord's song in a strange land?" are sufficient to illustrate my meaning, and among the daughters of Judea such names as Miriam, Deborah, and Judith, are especially known to us for their accomplishment in the vocal art, and as examples of the manner, in which it was cultivated by the women of Israel. Among the ancients, however, the Greeks most assuredly had the keenest perception and appreciation of the beauties and value of music. In the Heroic age it played a significant part in their sacred games, and for a man to acknowledge an ignorance of the principles of musical art, was to confess himself, an untutored boor. In the great tragedies of Sophocles and Euripides it figured largely both vocally and instrumentally, and, even as the Welsh have their Eisteddfod, so the classic Greeks had their competitions, in which choirs from various cities strove for vocal supremacy and the honours of prize-winners. That other great race of ancient times which fattened on the spoils of Europe and Asia – I refer to the Romans – treated the art with less concern, and employed it in a cruder form at the celebration of their victories and Bacchanalian revels. They did little or nothing to foster or develop it, although it is said that one of their most famous – or perhaps it would be better to say infamous – rulers was so devoted to music, that he fiddled while his capital was burning. But we may reasonably have our doubts as to Nero's claim to rank as the Sarasate of his time, for although he made public appearances as a virtuoso in his chief cities, and challenged all comers to trials of skill, the importance of his recorded victories is somewhat diminished, by the fact, that his judges were sufficiently wise in their generation, to invariably award him the honour of pre-eminence. It is a prudent judge who recognises a despotic Emperor's artistic – and other – powers. With the dawn of Christianity came a new era in the art, and in the 4th century, we find that a School of Singing was established at Rome, for the express purpose of practising and studying Church music. It was not, however, until another couple of centuries had elapsed, that the sound of music based on definite laws was heard beneath an English sky. You have to travel back in mind to that memorable procession of devoted monks, which, under the leadership of the saintly Augustine, wended its way into the little city of Canterbury, singing its Litany of the Church, and startling Pagan Britain with its joyful alleluia. Slowly, very slowly, the art progressed, but four more centuries were to pass before it was established on anything like a true scientific basis, and it is such men as Hucbald, a Flemish monk, Guido D'Arezzo and Franco of Cologne who laid the foundation of our whole system of polyphonic music. Before, however, I touch on that broader expanse, the era of the Flemish School, which began to attain noteworthy prominence in the early years of the 15th century, it would be as well, perhaps, to dwell for a few moments on the history of the noble instrument which is the cause of our foregathering here to-day. In a very early chapter in the Book of Genesis we are told that Jubal was "the father of all such as handle the harp and the organ," and therefore he ranks in history as the first teacher of music. It is commonly asserted, that the emoluments of the modern organist do not come well within the designation of "princely," and, judging from the limited population in those Adamite days, we may well assume that Jubal's living was almost as precarious as those worthy Shetland Islanders who depended for their subsistence on washing one another's clothes. With wise forethought, however, Jubal's brother had devoted himself to engineering. "He was the instructor of every artificer in brass and iron," and therefore, we may conclude there was money in the family, and that the man of commerce was generous to the man of music, even as we of to-day are ever ready to respond to the demands for assistance, on behalf of our local choral societies, and musical organisations. But it must not be supposed, that the organ presided over by Jubal bore any resemblance whatever, to the stately instrument, which will now voice its glorious tone within these walls, for the first time in public. The primitive organ of mankind has its present-day affinity in the charming instrument, which, in the hands and mouth of a precocious juvenile, has such a powerful and stimulating effect on the cultivated ears and sensitive nerves of the modern amateur. It is not possible for me to go into any detail, with regard to the slow and marvellous development of that triumph of human skill, which is truly known as the king of instruments. From those simple pieces of reed, cut off just below the knot, which formed the pipes of the syrinx, to the complicated, elaborate and perfect machinery which is hidden beneath the organ case there, is the same degree of difference, as there is between the rough-hewn canoe of the savage, and the wonderful perfection of the liners, which run their weekly race across the broad Atlantic. It was not until the end of the 11th century, that the first rude steps were taken towards the formation of the modern keyboard; then it was that huge keys or levers began to be used, and these keys were from 3 to 5 inches wide, 1-½ inches thick, and from a foot and a half to a yard in length. Nevertheless, even the organ of the 4th century had its impressive powers, if we may place reliance on words attributed to the Emperor Julian, the Apostate, who wrote: "I see a strange sort of reeds; they must, methinks, have sprung from no earthly, but a brazen soil. Wild are they, nor does the breath of man stir them, but a blast leaping forth from a cavern of ox-hide, passes within, beneath the roots of the polished reeds; while a lordly man, the fingers of whose hands are nimble, stands and touches here and there, the concordant stops of the pipes; and the stops, as they lightly rise and fall, force out the melody." And in its growth, as in the growth of young children, the organ has had its share of infantile vicissitudes. Even as late as the 13th century it lay under the ban of the ecclesiastics, and was deemed too profane and scandalous for Church use. Again, in 1644, Parliament issued an ordinance which commanded "that all organs and the frames and cases wherein they stand in all Churches and Chappells aforesaid shall be taken away and utterly defaced, and none other hereafter set up in their places." "At Westminster Abbey," we are told, "the Soldiers broke down the organs and pawned the pipes at several Ale Houses for pots of Ale." It is difficult to understand this opposition to the organ, more especially as David in the last of his psalms enjoined the people "to praise God with stringed instruments and organs." True, indeed, Job, in one of his most pessimistic moods, placed it on record that "the wicked rejoice at the sound of the organ," but evidently Job had no soul for music – was so unmusical, in fact, that he is worthy to be associated with a certain eminent divine of the English Church, whose musical instinct was so deficient that he only knew "God Save the Queen" was being sung by the people rising and doffing their hats. Before touching upon that scientific development of the art, which, broadly speaking, began with the advent of the Flemish School and reached its culminating point within the rounded walls of Bayreuth, we may well give a moment's consideration to those melodies, which travelled their unwritten way through the early Middle Ages, and which we know, by the few examples that have come down to us, to have been racy of the soil that gave them birth; the folk song of the country is more characteristic of its people, of their temperament and psychology, than any other attribute of their national existence. We, in England, have little enough to point to in this way; in a sense there is nothing peculiarly individual in our music as a whole. But with the old melodies of Ireland, that ever seem to tremble between a tear and a smile, and in the quaint pathos of Scotland's airs, and the well-defined beauty of typical Welsh songs, we recognise the true speech of the heart and the outpouring of the natural man. Germany is still richer in its folk music, and the Pole and the Russian, the Hungarian and the Gaul, can each point to a mine of original melody which has provided latter-day composers with the basis of their most beautiful works. Nor must the importance of the Troubadours and Minnesingers be overlooked in reference to this interesting phase of musical art. They it was who kept alive and spread abroad the traditional songs of the people, and by their accomplishment actually worked as an educational force on the people themselves. Readers of Chaucer will bear in mind many an allusion to the minstrel's art of his period, and well through the Norman and Plantaganet epochs.