полная версия

полная версияThe Operatic Problem

This principle pervades the uses and customs of the Italian theatrical world, and is applicable to the letting of scores by publishers, who, untrammelled by such institutions as the Société des Auteurs in France, or special laws as in Spain, can charge what they please for the hire of band parts and scores. There is nothing to prevent the publisher of Lucia di Lammermoor from letting the music of the opera for 50 francs (£2) to an impressario at Vigevano and charging 20,000 francs (£800) to another who produces it, say, at the Argentina of Rome, with Melba in the title-rôle.

The music publisher in Italy has a unique position amongst publishers, but quite apart from this, he enjoys so many prerogatives as to be almost master of the operatic situation in that country. He can put what value he pleases on the letting of the score he owns, and has the absolute right over the heads of the Theatrical Board to reject artists already engaged, including the conductor. He can take exception to costumes and scenery and withdraw his score as late as the dress rehearsal.

This is called the right of protesta. It does not follow that such right is exercised indiscriminately, spitefully or frequently, but it is sufficient that it exists, and what between the Commissione Teatrale, the palchettisti and the publisher, the impressario in Italy is not precisely on a bed of roses. Still, in spite of such impedimenta, Italian opera flourished for well-nigh two centuries, and Italian singers, repertory and language were considered all but synonymous with every operatic enterprise, during that period. This ascendency lasted as long as proper incentives for development of the art were steadily provided by responsible bodies; in other words, so long as the great theatres of Italy – La Scala at Milan, San Carlo at Naples, Communale at Bologna, Apollo at Rome, Fenice at Venice, Carlo Felice at Genoa, Raggio [transcriber: Regio?] at Turin, Pergola at Florence, etc. – were in receipt of regular subventions. But political and economical changes in the country turned the attention of public bodies towards other channels, and the radical tendencies of most municipalities went dead against the artistic interests of the country. In spite of warnings from most authoritative quarters, the opposition, towards subsidising what was wrongly considered the plaything of the aristocracy grew apace, and the cry became common that if dukes and counts, and other nobles wanted their opera, they should pay for it. Subsidies were withdrawn here, suspended there, cut short in another place, and altogether municipal administration of theatres entered upon a period the activity of which I have already qualified, as opportunistic and arbitrary. In vain did a great statesman, Camillo Cavour, argue the necessity of maintaining at all costs, the time-honoured encouragement, and help to pioneers of the Italian opera, bringing the discussion to an absolutely practical, if not downright commercial, level. "I do not understand a note of music," said he, "and could not distinguish between a drum and a violin, but I understand very well that for the Italian nation, the art of music is not only a source of glory, but also the primary cause of an enormous commerce, which has ramifications in the whole world. I believe therefore that it is the duty of the Government to help so important an industry." The municipalities remained obdurate, and the start of their short-sighted policy coincided with the gradual decadence of Italian opera, until this form of entertainment lost prestige, and custom with the best of its former clients, England, Russia and France. We know how things on this count stand with us. In Russia, Italian opera, formerly subsidised from the Imperial purse, was left to private enterprise, and all available funds and encouragement transferred to national opera houses; whilst in France the reaction is such, that even the rare production of an Italian opera in one of the French theatres is tolerated and nothing more.

Germany

The organisation of theatres in the German Empire is quite different and widely different the results! Let us take only the Court theatres (Hoftheater), such as the opera houses of Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Wiesbaden, Stuttgart, Carlsruhe and Darmstadt in Germany, those of Vienna and Prague in Austria, and the municipal theatre of Frankfort.

These theatres are under the general direction of Court dignitaries, such as H.E. Count Hochberg in Berlin and H.S.H. Prince von Lichtenstein in Vienna, and under the effective management of Imperial "Intendants" in Vienna and Berlin, a Royal "Intendant" at Munich, Dresden, Wiesbaden, Stuttgart and Prague, Grand-Ducal at Carlsruhe and Darmstadt, and municipal at Frankfort.

The "Intendants" do not participate either in the risks or profits of the theatre, but receive a fixed yearly salary varying between 20,000 and 30,000 marks (£1000 to £1500). They have absolute freedom in the reception of works, the engagements of artists, the selection of programmes and repertory, and are answerable only to the Sovereign, whose Civil List provides the subsidy, balances accounts, and contributes to the settling of retiring pensions of the personnel.

The Berlin Opera House receives a yearly subvention of 900,000 marks, or £45,000.

The Vienna Opera House has 300,000 florins (about £25,000) for a season of ten months. The deficit, however, if any, is made good from the Emperor's Privy Purse.

The King of Saxony puts 480,000 marks (£24,000) at the disposal of Count Intendant Seebach. It is interesting to note that in 1897 only 437,000 marks were actually spent. The orchestra of the Dresden Opera House does not figure in the budget, its members being Royal "servants" engaged for life and paid by the Crown.

At Munich it is the same, the orchestra being charged to the Civil List of the Regent of Bavaria. The cost is 250,000 marks (£12,500), and a similar sum is granted to Intendant Possart for the two theatres he manages (Hof and Residenz). The season lasts eleven months.

Wiesbaden comes next with a subvention of 400,000 marks, (£20,000) granted by the Emperor of Germany as King of Prussia. The season is of ten months' duration.

The Court Theatre at Stuttgart is open for ten months, and the Royal subvention to Baron von Putlitz, the Intendant, is 300,000 marks (£15,000).

The same sum is granted by the Grand Duke of Baden to the Carlsruhe theatre for a season of ten months.

The subvention of Darmstadt is only 250,000 marks (£12,500), the season lasting but nine months.

The States of Bohemia grant a sum of 180,000 florins (£15,000 odd) to the theatres of Prague for a season of eleven months. 100,000 florins (£8000 odd) of this sum are destined for the National Tcheque Theatre.

Frankfort, as an ancient free city, does not enjoy the privileges of princely liberality, and has to put up with municipal help, which amounts to a yearly donation of 200,000 marks (£10,000) for a season of eleven months, and then the Conscript Fathers contrive to get one-half of their money back by exacting a duty of 30 pfennigs on every ticket sold. A syndicate, with a capital of £12,500, has been formed to help the municipal institution. – Mr Claar.

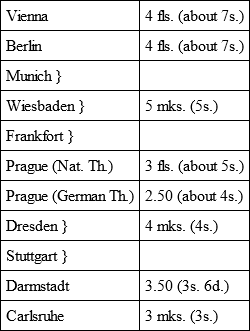

The chief advantages of Court theatres consist in a guarantee against possible deficit, and freedom from taxes; and this enables the Intendants to price the seats in their theatres, in a manner which makes the best opera accessible to the most modest purse. The prices of stalls in German theatres vary between 3 and 6 marks or 3 to 4 florins. (3s. to 6s. or 7s). Other seats are priced in proportion, and a considerable reduction is made in favour of subscribers. These are simply legion, and at Wiesbaden the management have been compelled to limit their number.

The table below, shows at a glance the price of stalls in some of the chief German theatres. I give the average figure, the price varying according to the order of the row.

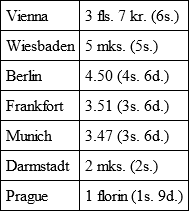

The subscriptions are divided into four series, giving each the right to two performances weekly, but of course anyone can subscribe for more than one series. A yearly subscription comprises – at Berlin and Prague, 280 performances; at Vienna, 260; at Munich, 228; at Wiesbaden, 200; and at Frankfort, 188. To subscribers the prices of stalls are as follows: —

These figures suffice to prove the colossal benefit princely patronage and subvention bestow on the theatre-goer, in putting a favourite entertainment within the reach of the masses. Moreover, the German opera-goer is catered for both in quality and quantity.

As regards quality, he has the pick of the masterpieces of every school, nation and repertory. Gluck, Spontini, Cherubini, Auber, Hérold, Boieldieu, Mozart, Beethoven and Weber hobnob on the yearly programmes with Wagner, Verdi, Mascagni, Puccini, Giordano and Leoncavallo, to cite a few names only. As regards quantity, the following details speak for themselves – I take the theatrical statistics for the year 1895-1896: —

The Berlin Opera House produces 60 various works – 52 operas and 8 ballets.

The Vienna Opera House 74 works – 53 operas and 21 ballets.

The New German Theatre at Prague – 45 operas, 11 light operas and two ballets.

The Frankfort Theatre – 60 operas, 11 operettes, 4 ballets and 13 great spectacular pieces.

At Carlsruhe – 47 operas and 1 ballet.

At Wiesbaden – 43 operas and 6 ballets.

At Darmstadt – 48 operas, 2 operettes and 5 ballets.

At Hanover – 37 operas.

At the National Theatre, Prague – 48 operas and 6 ballets.

At Stuttgart – 53 operas and 5 ballets.

At Munich – 53 operas and 2 ballets.

At Dresden – 56 operas, 5 ballets and 4 oratorios.

These are splendid results of enterprise properly encouraged, and I am giving only a fraction of the information in my possession, for there are no less than ninety-four theatres in Europe, where opera is performed in German, and of these seventy-nine are sufficiently well equipped to mount any great work of Wagner's, Meyerbeer's, etc.

Most of these theatres produce every year one new work at least, and thus the repertory is constantly renewed and augmented.

Every German theatre has attached to it a "choir school," where girls are admitted from their fifteenth year and boys from their seventeenth. They are taught solfeggio and the principal works of the repertory. The classes are held in the early morning, so as not to interfere with the pursuit of the other avocations of the pupils; but each receives, nevertheless, a small yearly salary of 600 marks (£30). These studies last two years, and during that time the pupils have often to take part in performances, receiving special remuneration for their services. When they are considered sufficiently well prepared, they pass an examination, and are appointed chorus-singers at a salary of 1000 to 1800 marks (£50 to £90) a year, and are entitled besides to a special fee (Spielgeld) of 1s. 6d. to 2s. 6d. per performance for an ordinary chorus-singer, and 2s. to 5s. for a soloist. If we reckon that a chorus-singer, can take part on an average in some 250 performances in a year, at an average fee of, say, 2s. each, we find that his income is increased by a sum of £25, a very decent competence. Nor is this all. In the smallest German towns, in the most modest theatres, there exist "pension funds" for all theatrical artists and employés. These funds are fed: —

(1.) By a yearly donation from the Sovereign's Privy Purse.

(2.) By retaining from 1 per cent. to 5 per cent. on the salaries of members.

(3.) From benefit concerts and performances.

(4.) From all kinds of donations, legacies, fines, etc.

At Stuttgart the King takes charge of all the pensions, except of those of widows and orphans, who are provided for from another fund.

At Munich the King furnishes the original capital with a sum of 200,000 marks (£10,000), and to-day the fund has over 1,000,000 marks at its disposal. Eight years' service entitles a member to a full pension.

At Prague six years' service gains a pension, but the average period throughout Germany is ten years.

There are scores of additional points of great interest, in connection with the working of German subsidised theatres. The above suffices, however, for the purpose of showing the immense advantage of a system of State-aided Art, a system that might serve as a model to a country about to embark on similar enterprises. I will add one detail more. There being no author's society in Germany, as in France, the theatrical managers treat with music publishers direct for the performing rights of scores which they own. The old repertory costs, as a rule, very little, and the rights of new works are charged generally from 5 per cent. to 7 per cent. on the gross receipts. Moreover, band parts and scores are not hired, as in Italy, but bought outright, and remain in the library of the theatre.

France

In France the State intervenes directly in theatrical matters in Paris only, subsidising the four chief theatres of the capital – to wit, the Opéra, the Opéra Comique, the Comédie Française and the Odéon.

In the provinces theatres are subsidised by municipal councils, who vote each year a certain sum for the purpose. The manager is appointed for one year only, subject to his acceptance of the cahier des charges, a contract embodying a scheme of stipulations devised by the council, and imposed in return for the subsidy granted. The least infraction of the conditions laid therein brings its penalty either in the way of a fine or the forfeit of the contract. The subsidies vary according to the importance of the town, the theatres of Lyons, Bordeaux and Marseilles being the three best endowed. Less favoured are places like Rouen, Lille, Nantes, Dijon, Nancy, Angers, Reims, Toulouse, etc., and, though the Chamber of Deputies votes every year in the Budget of Fine Arts a considerable sum for the provinces, the subsidy is not allotted to theatres, but to conservatoires, symphonic concerts and orpheonic societies. Two years ago a Deputy, M. Goujon, obtained in the Chamber the vote of a special grant for such provincial theatres as had distinguished themselves by producing novelties. But the Senate threw out the proposal.

It is not, however, as if the Government of the Republic were indifferent to the fate of the provincial theatres or their progress in the field of operatic art. But worship of Paris on one side, and a dislike to decentralisation on the other, are responsible for the fact that all efforts are directed towards one channel, namely, the four before-named Parisian theatres. Of these, naturally enough only the opera house will engage my attention, or more precisely one alone, the Grand Opera House, La Théâtre National de l'Opéra, there being little practical difference between the working of that and of the younger house, the Théâtre de l'Opéra Comique.

A few words, following chronologically the various stages through which the Paris Opera House has passed since its origin, may prove of interest, and serve to indicate how untiring has been the care of successive Governments over the fortunes and the evolution of the operatic problem in France.

It will be remembered that Pierre Perrin was the possessor of the first operatic privilege granted by Louis XIV. in 1669. Hardly had he been installed when Lulli began to intrigue against his management, and having learnt that the profits of the first year amounted to over 120,000 livres, he had no rest until he obtained, through the influence of Mme. de Montespan, the dismissal of Perrin and obtained the post for himself. In fifteen years his net profits amounted to 800,000 livres!

He was succeeded by his son-in-law, Francine, who held the privilege with various fortunes until 1714, the King intervening more than once in the administration. In 1715 the Duc d'Antin was appointed Regisseur Royal de l'Académie by letters-patent of the King, who up till then considered himself supreme chief of his Academy.

In 1728 the management passed into the hands of Guyenet, the composer, who in turn made over the enterprise, for a sum of 300,000 livres, to a syndicate of three – Comte de Saint-Gilles, President Lebeuf and one Gruer. Though their privilege had been renewed for thirty years, the King, Louis XV., was obliged to cancel it owing to the scandal of a fête galante the syndicate had organised at the Académie Royale, and Prince de Carignan was appointed in 1731 inspecteur-general. A captain of the Picardy regiment, Eugene de Thuret, followed in 1733, was succeeded in 1744 by Berger, and then came Trefontainé, whose management lasted sixteen months – until the 27th of August 1794. All this was a period of mismanagement and deficits, and the King, tired of constant mishaps and calls upon his exchequer, ordered the city of Paris to take over the administration of his Academy. At the end of twenty-seven years the city had had enough of it, and the King devised a fresh scheme by appointing six "Commissaires du Roi pres la Académie" (Papillon de la Ferte, Mareschel des Entelles, De la Touche, Bourboulon, Hébert and Buffault), who had under their orders a director, two inspectors, an agent and a cashier. But the combination was short-lived, lasting barely a year. In 1778 the city of Paris made one more try by granting a subvention of 80,000 livres by a Sieur de Vismos.

In 1780 the King took back from the city the operatic concession – we must bear in mind it was a monopoly all this time – appointing a "Commissaire de sa Majeste" (La Ferte) and a director (Berton).

In 1790 the opera came once more under the administration of the city, and during the troublous times of the Revolution changed its name of Académie Royale to that of Théâtre de la République et des Arts.

By an Imperial decree of the 29th of July 1807 the opera came under the jurisdiction of the first Chamberlain of the Emperor, whilst under the Restoration the Minister of the King's Household took the responsibilities of general supervision. One Picard was appointed director under both régimes, and was succeeded by Papillon de la Ferte and Persius. Then followed the short management of Viotti, and in 1821 F. Habeneck was called to the managerial chair.

The Comte de Blacas, Minister of the King's Household, became superintendent of Royal theatres, and after him the post was occupied by the Marquis de Lauriston, the Duc de Doudeauville and the Vicomte Sosthenes de la Rochefoucauld. Habeneck was replaced by Duplantis, who took the title of Administrator of the Opera. The administration of M. de la Rochefoucauld cost King Louis Philippe 966,000 francs in addition to the State subvention, and an extra subsidy of 300,000 francs derived from a toll levied in favour of the opera on side shows and fancy spectacles. This was in 1828, and in 1830 the King, finding the patronage of the opera too onerous for his Civil List, resolved to abandon the theatre to private enterprise. Dr Veron offered to take the direction of the opera house, at his own risk, for a period of six years with a subsidy of 800,000 francs, and, with the exception of a period of twelve years (1854-1866), the administration of the opera was included in the duties of the Master of the Emperor's Household. Both the subsidy and the principle of private enterprise have remained to this day as settled in 1830. Before then, for 151 years, French opera had enjoyed the patronage and effective help of the Sovereign, or the chief of the State, very much on the same system as obtains at the present day in Germany.2

Dr Veron had as successors, MM. Duponchel, Leon Pillet, Nestor Roqueplan, Perrin, Halanzier, Vaucorbeil, Ritt and Gailhard, Bertrand and Gailhard, and finally Pierre Gailhard, the present director of the Théâtre National de l'Opéra.

The present relations in France between the State and the director of the opera are as follows: —

The Paris Opera House, like all other theatres in France, and for the matter of that all institutions in the domain of Art in that country, is under the direct control and dependence of the Minister of Fine Arts, who has absolute power in appointing a director, in drawing up the cahier des charges, in imposing certain conditions and even in interfering with the administration of the theatre. The appointment, called also the granting of the privilège, is for a number of years, generally seven, and can be renewed or not at the wish or whim of the Minister. The cahier des charges, as already stated, is a contract embodying the conditions under which the privilège is granted. Some of these are at times very casuistic. As regards interference, one can easily understand how a chief can lord it over his subordinate if so minded. It is sufficient to point out the anomaly of the director's position who is considered at the same time a Government official and a tradesman – a dualism that compels him to conciliate the attitude of a disinterested standard-bearer of national art with the natural desire of an administrator to run his enterprise for profit. Let me cite a typical instance. Of all the works in the repertory of the opera, Gounod's Faust still holds the first place in the favour of the public, and is invariably played to full or, at least, very excellent houses, so that whenever business is getting slack Faust is trotted out as a trump card.3 Another sure attraction is Wagner's Walküre. On the other hand, a good many operas by native composers have failed to take the public fancy, and have had to be abandoned before they reached a minimum of, say, twenty performances in one year. Now, when the director sees that his novelty is played to empty houses he hastens to put on Faust or the Walküre, but the moment he does it up goes a cry of complaint, and a reproof follows – "You are not subsidised to play Faust or operas by foreign composers, but to produce and uphold the works of native musicians; you are not a tradesman, but a high dignitary in the Ministry of Fine Arts," and so on.

At other times, when in a case of litigation, the director wishes to avail himself of the prerogatives of this dignity, he is simply referred to the Tribunal de Commerce, as any tradesman. Ministerial interference is exercised, however, only in cases of flagrant maladministration, and then there are, of course, directors and directors, just the same as there are Ministers and Ministers.

It is needless to go over the whole ground of the cahier des charges, the various paragraphs of which would form a good-sized pamphlet. The cardinal points of the stipulations between the contracting parties are, that the director of the Paris Opera House receives on his appointment possession of the theatre rent free, with all the stock of scenery, costumes and properties, with all the administrative and artistic personnel, the repertory, and a yearly subsidy of 800,000 francs (£32,000).

In return for this he binds himself to produce every year a number of works by native composers, and to mount these in a manner capable of upholding the highest standard of art, and worthy of the great traditions of the house. This implies, among others, that every new work must be mounted with newly-invented scenery and freshly-devised costumes, and that in general, no one set of scenery, or equipment of wardrobe, can serve for two different operas, even were there an identity of situations or historical period or any other points of similarity. Thus, if there are in the opera repertory fifty works, necessitating, say, a cathedral, a public square, a landscape or an interior, the direction must provide fifty different cathedrals, fifty different public squares, fifty varying landscapes, etc. The same principle applies to costumes, not only, of the principal artists, but of the chorus and the ballet. Only the clothes and costumes of definitely abandoned works can be used again by special permission of the Minister of Fine Arts.

As regards the new works that a director is bound to produce every year, not only is their number stipulated, but the number of acts they are to contain, and their character is specified as well. This is in order to avoid the possible occurrence of a production, say, of two works each in one act, after which exertion a director might consider himself quit of the obligation. It is plainly set out that the director must produce in the course of the year un grand ouvrage, un petit ouvrage, and a ballet of so many acts each – total, eight, nine or ten acts, according to the stipulations. Moreover, he is bound to produce the work of a prix de Rome– that is to say, of a pupil of the Conservatoire, who has received a first prize for composition, and has been sent at the expense of the Government to spend three years at the Villa Medicis of the Académie de France in Rome. Owing to circumstances, the Minister himself designates the candidates for this ex-officio distinction, guided by priority of prizes. The director had recourse to this measure through the fault of the prix de Rome themselves, who, over and over again, either had nothing ready for him or else submitted works entirely unsuitable for the house. The Minister's nomination relieves the director of responsibility in such cases.