полная версия

полная версияThe Kacháris

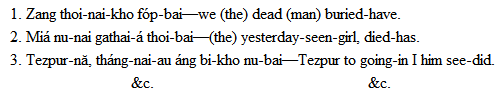

In the same way the passive participle in nai can be (1) declined as a noun, or (2) used as an adjective, or (3) take the place of a relative pronoun; e. g.—

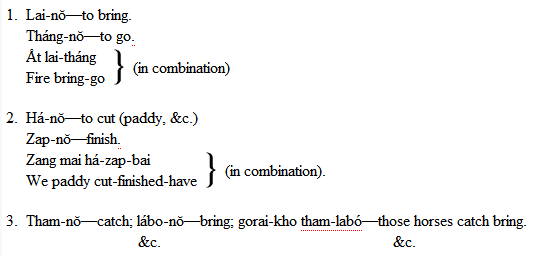

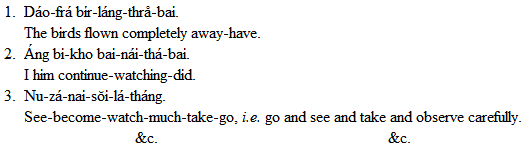

The great and characteristic feature of the Syntax of the language is the remarkable way in which verbal roots, mostly monosyllabic, are combined together to form a very large and useful class of compound verbs. In this way the use of conjunctions &c. is very largely avoided, and the language becomes possessed of a vivid force and picturesqueness often wanting in more cultivated tongues. These compound verbs may perhaps be roughly classified under two groups, e. g.—

I. – Those in which each verbal root has a distinct meaning and may be used separately; —

II. – Those in which one or more of the verbal roots is never used separately but in combination only. As illustrations of class I. the following may be mentioned: —

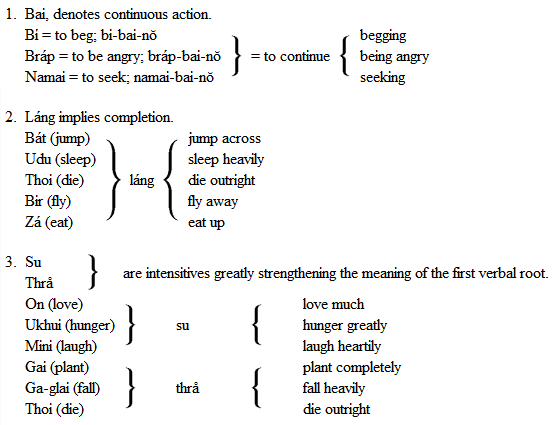

The compound verbs of Class II. are very numerous and in frequent use. A few illustrations only can be given here, which may serve to show that the second and subsequent members of the agglutinative verb, while they have no independent existence, yet serve to enrich and expand the meaning of the primitive root in a very remarkable way.

In not a few cases several, sometimes as many as five or six, of these infixes are combined with the original verbal stem, each one materially contributing to enlarge and enrich its meaning. A few illustrations are here supplied.

From what little has been here stated it would seem to be fairly obvious that the language in its original form is strictly an agglutinative one. But a gradual process of deglutinisation has for some time been going on, no doubt originating through intercourse with neighbours speaking languages of quite another type, e. g. Assamese, Bengali, &c. Most Kacháris (Bårå) in this district are quite familiar with Assamese; indeed, it is very rarely that the writer has met with men who did not know this form of Aryan speech. Now a Kachári in the habit of speaking Assamese will, even when using his own mother tongue, to which he is strongly attached, not infrequently resort to a partially inflected form of expression instead of restricting himself to the use of infixes, &c. This gradual change in the language is especially brought out in the usage of the participial forms of the verb. It has been shown above, e. g. that the past participle (passive) can be declined like a noun. Again, in expressing a simple sentence like the following: —

I ran and caught and brought the horse an Assamese speaking Kachári would probably make use of the active participle in ná-nŏi; whilst his more primitive brother, who might be less familiar with Assamese, would confine himself to the more idiomatic use of infixes. Thus the sentence given above might be expressed in two ways:

It would seem to be not improbable that the language may gradually lose its agglutinative character, and approximate to the inflected type, though the process most likely will be but a slow one, owing to the very clannish temperament of the people which makes them cling strongly to anything they regard as their very own, e. g. their language (cf., a somewhat similar state of things in Wales and the Scottish Highlands). But in its present stage the language is one of no small interest to the student of comparative philology, because it is an apt illustration of a form of speech which, once strictly agglutinative, is now in process of learning inflexion through the pressure of contact with the speakers of Aryan tongues.43

APPENDIX I

I. – Tribes closely allied to KachárisIn a former section, something has been said in favour of the idea that the Kachári race is a much more widely distributed one than was supposed to be the case some years ago; and members of this race under different names still occupy large areas in north-eastern India. It may be useful to add a few brief notes on some of the principal of these closely cognate tribes, confining our notice mainly to those points and details wherein they differ more or less from the Kacháris of Darrang, whose language, habits, religion, etc., as described above, may perhaps be provisionally taken as a standard.

1. Garos.– One of the most important of these allied races is undoubtedly that known to us as the Garos, dwelling in what is called the Garo Hills District. This tribe, like the people of the North Cachar Hills, has until recent years been largely confined to the part of Assam which bears it name, and has not come into contact with Hinduism to any great extent, and hence it has in all likelihood preserved its aboriginal manners and customs almost intact. But it is not necessary here to do more than merely mention the name of this interesting people, as their whole manner of life has been sufficiently dealt with elsewhere by a highly competent hand.44

2. Mech (Mes). 70,000. – Nor is it necessary to do much more for the people known as Mech (Mes) who are undoubtedly merely a branch (the western one) of the Bårås of Darrang. The name is almost certainly a corruption of the Sanskrit word mleccha, i. e., an outcast from the Brahmin point of view, a non-observer of caste regulations; such persons being in the light of modern Hinduism very much what the barbarian was to the Greek, or the “Gentile” to the Jew, some twenty centuries ago. This term mlech (mech) is not in use here (Darrang) or in Kamrup.

Subdivision. The uncomplimentary epithet “mlech padre” has sometimes been hurled at the writer when preaching to Brahmins or other high caste Hindus, though it would seem to be the recognised name for the Bårå race from the Manás river westwards to the neighbourhood of Jalpaiguri. They would seem to be especially numerous in Goalpara district, where one of the principal landholders is known as the “Mech-párá zamindár.” Some sixteen exogamous septs are recognised among the Meches, of which the most important would seem to be the following: —

1. Meshá-árŏi – the tiger folk

2. Bánsbár-árŏi – bamboo folk

3. Dŏim-árŏi – water folk

4. Goibár-árŏi – betelnut folk

5. Swarg-árŏi – heaven folk.

Of these the last-mentioned, which is obviously of Hindu origin, is looked upon as the highest, whilst the names of the remaining four are apparently of totemistic origin. The first on the list, Mashá-arŏi (tiger folk; Mashá, tiger), still retains a certain hold on the regard of the members of its sept, all of whom go into a kind of mourning (see above) when a tiger is found lying dead near one of their villages.

Origin. Nothing definite is known as to the origin of the Meches; by some they are said to be descended from Bhim and Hidamba, whilst others maintain that they are the descendants of Turbasu, son of Raja Jajáti, who fell under his father’s curse, his children thus becoming outcasts (Mlecchas).

Religion. Their religion is distinctly of the Animistic type with a tendency towards Hinduism, Batháu being replaced by Śiva in some cases. The siju tree is regarded with much reverence, and is to be seen in the courtyard of most Mech houses, much more frequently than among the Kacháris of this district. This sacred tree is sometimes used as a means of divination or detecting crime or other misdoings in domestic life.

Marriage and funeral ceremonies.

In all ceremonies relating to marriage and funerals, what has been already said of the Kacháris holds good almost word for word of the Meches. But speaking generally it may be said that the marriage rites among the Meches are more simple than among the Kacháris, the essential features being the exchange of betel-leaves and areca-nuts between bride and bridegroom followed by the offering of a cock and hen in sacrifice to Batháu or Śiva. The funeral ceremonies, on the other hand, among the Meches are perhaps somewhat more elaborate than is the case with the Kacháris (Bårå), as an informal Shrádh has to be performed by them, by the son or daughter of the deceased Mech, seven or nine or eleven days after death, and sometimes on the day of the funeral itself, an indication that Hindu customs are creeping in among this portion of the Bårå race.

3. Rábhás (70,000). The name of this tribe (Rábhás) is of uncertain derivation and in this district (Darrang) the people themselves are sometimes called Totlás, which may perhaps be a nickname. Another term used in designating them is Dătiyál Kachári, i. e. Borderer Kacháris (dáti– border, edge, boundary); and it is held by some that their original home and Habitat.habitat was the region bordering on the northern slopes of the Garo Hills. This supposition is partly confirmed by the fact that the only words in their language to express (1) north and (2) south, respectively, are (1) Bhotá hi-chu, Bhotan Hills,45 and (2) Tura; their physical horizon being apparently absolutely limited by the two localities thus designated; moreover, Rábhás in somewhat large numbers are still to be found at the base of the northern slope of the Garo Hills. Some 30,000 have their home in Goalpara district, whilst others are located in Kamrup, north-west Darrang, and among the Garos in their hills. Origin (traditional).Their origin is but imperfectly known, but they are said to be descended from a Hindu father who lost caste by marrying a Kachári woman. Their Language.language, which would seem to be rapidly dying out, forms a very interesting link between Garo and Kachári, having much in common with both, but with some special features peculiar to itself. Like the tongue of other branches of the Bårå race, the Rábhá language, at one time undoubtedly agglutinative, seems to be in process of becoming inflexional, through contact and intercourse with the speakers of more or less broken-down Sanskritic languages, e. g., Bengali, Assamese, etc. Some Subdivisions.seven sub-tribes are said to be still recognised among the Rábhás, i. e., Rangdaniya, Maitariyá, Páti-Koch, Bitliyá, Dáhuriyá, and Sanghá. The members of the three sub-tribes first in this list occupy a position of some eminence above the others, and are at liberty to intermarry among themselves. They are, however, so far “hypergamous” that if any one of their members should marry into any of the last four sub-tribes, the person so marrying would have to pay a fine of Rs. 100, or upwards, to the members of the lower sub-tribe concerned. As regards Social (caste) status.caste-position and status, the Rábhás hold themselves to be slightly higher than the pure Kacháris, e. g., the Rábhá will not eat rice cooked by a Kachári, though the latter freely partakes of food prepared by a Rábhá. On the other hand, the Rábhá eats and drinks quite as freely as does the Kachári, and intermarriage between the two branches of the race is not very uncommon, a young Kachári bridegroom selecting a Rábhá bride having to make his peace with her people by giving them a feast and paying a bride-price (gá-dhan) on a somewhat enhanced scale. The children born of such a “mixed marriage” belong to the father’s tribe. Kacháris sometimes formally enter the Rábhá community, though it is not necessary for them to do so, on their way to Hinduism. A Kachári wishing to be received into the Rábhá sub-tribe has to pass through a somewhat elaborate initiation, which may be briefly summarised as follows: —

Admission of a Kachári convert into the Rábhá community. “A deori (Priest) divides a pig into seven pieces in front of the convert’s door, and disposes of them by throwing away one such piece towards each of the four cardinal points; while of the remaining three pieces one is thrown skywards, a second earthwards, and the last Patálwards.46 At the same place he then proceeds to cook a fowl and prepares therefrom a curry, which he divides into seven equal parts; and arranging these portions on the ground he leaves them there, after sprinkling them with pad-jal.47 This part of the ceremonial is known as chíládhar, or báodhar katá, i. e., forms of making práyaś-chitta (reconciliation). The deori then lays down a plantain-leaf on the courtyard and places on it a lighted lamp, a handful of rice, a betel-leaf, and an areca-nut, together with some tulasi leaves and a few copper coins. The convert is then made to drink pad-jal in public, and after this he must pay at least one rupee to the assembled people, and treat them to two vessels full of rice-beer (mådh). He is further required to entertain liberally the members of his newly-acquired brotherhood for three successive evenings, pork and mådh forming the principal materials of the feast.”

Religion. Very little need be said under the head of religion; for in this respect they are but little separated from the closely-cognated Kachári (Bårå) race. The general type of the Rábhá religion is distinctly animistic; but one or two of the higher subdivisions, especially the Pátis, are said to show a leaning towards Hinduism of the Śákta form, the deity chiefly worshipped being known as Bhalli (? Bhareli), to whom puja is done in Kārtik, Māgh and Baisākh. There are no temples or fixed places of worship, nor are Brahmins employed; the deori (deosi) doing all that is deemed necessary in public religious ceremonies.

Relations of the sexes. Marriage is almost invariably adult, and is usually entered into by payment to the bride’s parents, or by servitude as among the Kacháris. Cases of ante-nuptial unchastity would seem to be rare; but when an unmarried girl does become pregnant, she is compelled to disclose the name of her lover, often through the siju-ordeal process (see above), and public opinion forces the seducer to marry his victim, paying a somewhat higher bride-price (gá-dhan) than he would otherwise have done. Monogamy is the rule in marriage, but public opinion permits the taking of a second wife when the first proves childless. Divorce is permitted for adultery, but would seem to be comparatively rare: widows are at liberty to marry whomsoever they will, except the deceased husband’s elder brother, a second bride-price being sometimes paid to the bride’s parents. The marriage ceremony itself is very simple, the essential features being (1) the exchange of betel-leaves and areca-nuts by bride and bridegroom, and (2) the formal sacrifice of a cock and hen, the latter being made into a curry of which bride and bridegroom partake together. The dead are disposed of generally by cremation, though in cases of destructive epidemics, e. g., cholera, kálá-azár, etc., known as “sirkári rog,” the bodies of deceased people are either hastily buried, or simply thrown into the neighbouring jungle.48

4. Hajongs – Haijongs. (8,000). About the small tribe (8,000 souls) known as Hajongs or Haijongs only very little definite information can at present be obtained; but it seems probable on the whole that they are a branch of the widely spread Bårå race. The tribal name is of uncertain derivation, but it is not unlikely that it is connected with the Kachári word for mountain or hill (ha-jo); and this supposition receives, perhaps, some little confirmation from their present known habitat, i. e., the southern slope of the Garo Hills, and the sub-montane tract immediately adjoining it. It is possible that these people may be the modern representatives of the inhabitants of the old kingdom of Koch Hajo, which corresponds roughly with the present district of Goalpara. It is known that during the period 1600–1700 this part of the country was overrun by Musalmán invaders, when many of the inhabitants probably took refuge in the Garo Hills, returning therefrom, and settling in the adjoining plains at the foot of these hills, when the pax Britannica gave them a certain amount of security for life and property. In appearance and dress the people are said to have a close resemblance to the well-known Kachári type, but this resemblance hardly holds good of their language as now spoken, for this is little more than a medley of Assamese and Bengali.

Religion. There are said to be two recognised subdivisions among them, i. e., (1) Byabcháris and (2) Paramárthis. The latter are largely Hinduized (Vaishnabs) and abstain from pork and liquor, etc.; whilst the former, who are Śáktas to a large extent, follow the practice of their Garo neighbours in matters of diet, etc. In spite, however, of this distinction of meats, it is said that members of the two sections of the tribe freely intermarry with each other. No Brahmins seem to be employed among them, any leading member (adhikári) of the village pancháyat doing what is customary at all marriages, etc. It may be added that the siju tree (euphorbia splendens) which occupies so important a place in the social and religious life of the Bårå, Meches, etc., on the north of the Brahmaputra does not seem to enjoy any special regard or respect among the cognate tribes (Haijangs, Dimásá, etc.) who have their homes on the south and east of that great river.

Relations of the sexes, marriage, &c. As among other members of the Bårå race, the relations of the sexes are on the whole sound and wholesome; ante-nuptial unchastity is but of rare occurrence, but when it does take place and pregnancy follows, the seducer is compelled to marry the girl, and to pay a certain fine of no great amount to the village elders. This form of union is known as a dái-márá marriage. But generally, as among the Kacháris of Darrang, the parents of bride and bridegroom arrange for the marriage of the young people, which always includes the payment of a bride-price (pån) of from 20 to 100 rupees to the bride’s parents, or the equivalent in personal service. It is said that among the “Paramárthi” subdivision, who are largely Hinduized, the betrothal of children is coming into vogue, but as a rule marriage is still adult, and for the most part monogamous. A second wife is allowed when the first proves to be childless, but polyandry is quite unknown. Divorce is permitted for adultery but is very rare, and under no circumstances can a woman be divorced when in a state of pregnancy. The divorce itself is effected in the usual way by the husband and wife tearing a betel-leaf in the presence of the village elders, and formally addressing each other as father and mother, showing that the relation of husband and wife has ceased. Widows can marry again, and do so freely, the one restriction being that no widow can marry her deceased husband’s brother, whether older or younger than her first partner. Here again, too, it would seem that Hindu influence is making itself felt, for it is said that the remarriage of widows is looked upon with growing disfavour. Property, both movable and immovable, is usually divided equally among the sons of a family (cf. the old Saxon law of “gavelkind”), anything like primogeniture being unknown. In a formal marriage among well-to-do people a certain ceremonial is observed. A square enclosure is formed by planting a plantain-tree at each corner, and within this enclosure are placed sixteen lighted lamps, and sixteen earthenware pots full of water, the bridegroom taking his stand in their midst. The bride then formally walks around him seven times, and then finally takes a seat at his left side, her face being turned towards the east. No mantras, etc., are recited, nor is any Brahmin present; but some village elder (adhikári) sprinkles water over the couple from one of the water pots, and the ceremony is held to be complete.

Disposal of dead. The bodies of the dead are occasionally buried or committed to the jungle, but this is done but rarely, probably only under the pressure of panic during an epidemic of cholera, etc. Cremation is almost universal, the head of the deceased being placed towards the north, the face looking upwards in the case of a man, and downwards in that of a woman. A Sráddha usually follows either on the tenth, or the thirtieth, day after the cremation.

5. Moráns (5,800); Animistic, 100; Hinduized, 5,700. Not much is definitely known about this small tribe, whose numbers do not exceed 6,000 in all; but although they are said to repudiate all connection with the Bårå race, it may be safely inferred that they do in reality belong to it; for on this point the evidence of language is fairly conclusive.49 They are sometimes known as Names.(1) Morán Kacháris and (2) Kapáhiyás (kapáh– cotton), the latter name being due to the fact that in early days one of their chief duties was to grow cotton for the use of Áhom princesses, at Kákatal, Moriáni, Jhánzi, Hologápár, etc. Their present Habitat.habitat may be roughly described as the country lying between the Buri Dihing and the Brahmaputra in the north-eastern part of the Province at least one-half of their number being located in the district of Lakhimpur, and the remainder in the adjoining portions of the Sibsagar district. Their chief centre is said to be a place known as Kákatal, the residence of the Tiphuk Gosain, the head of the Matak clan, with the members of which the Moráns are said to fraternize and even to intermarry freely.

Origin (traditional). The original home of the Moráns is said to have been at Mongkong (Maingkhwang) in the Hukong Valley at the upper reaches of the Chindwin river, where some centuries ago resided three brothers Moylang, Morán, and Moyrán. Of these, Moylang, the eldest, remained in the Hukong Valley, whilst the youngest, Moyrán, migrated into Nipál, and was there lost sight of; and Morán, the second brother, passed the Patkoi range into Assam and, settling on the Tiphuk river, became the ancestor of or at least gave its present name to the Morán tribe. But however this may be, it is fairly certain that, when the Áhoms passed into Assam about the middle of the thirteenth century, they at once came into conflict with the Moráns, whom they seem to have subdued with but little difficulty. By their Áhom conquerors the Moráns were employed in various menial capacities, as hewers of wood and drawers of water, and were sometimes known as Hábungiyás,50 earth-folk, or true autochthones, “sons of the soil,” though they seem to have intermarried freely with their Áhom rulers. But in spite of their subordinate position in political life the Moráns, like other branches of the Bårå race, have sturdily maintained some of their national characteristics to this day, e. g., their language, though apparently doomed to early extinction, is still to some extent retained by members of the clan.

Religion. In the census of 1891 only 100 Moráns are returned as animistic, the great bulk of them being described as Hindus of the Vaishnab.Vaishnab type. Their Hinduism, however, would seem to be of a somewhat lax character; for though they do not eat beef, pork, or monkeys, or drink madh and photiká, yet they freely partake of all kinds of poultry and fish, with the tortoise, grasshopper, etc. No social stigma, too, attaches to the catching and selling of fish to others. No idols are to be seen in their villages, nor are Brahmins ever employed in religious ceremonials, certain officials known as Medhis and Bhakats doing all that is deemed necessary on these occasions. On certain great social gatherings known as Sabhá (Samáj), which are apparently not held at any fixed periods, there is much singing, beating of drums (Mridang) and cymbals (tál) in honour of Krishna, to whom offerings of rice, salt, plantains, betel-nuts, are freely made. In earlier times it is said that there were three chief centres (satras) of the religious life of the Moráns; each presided over by an elder known as the burá or dángariyá. These were the (1) Dinja (Kachári burá), (2) Garpará (Áhom burá), and (3) Puranimáti (Khátwál burá). These dángariyás are said still to retain a position of some spiritual influence among the Moráns, all religious teaching being in their hands. Each family may freely choose its own dángariyás, but followers of one dángariyá will not eat food cooked by those of another, even when the worshippers are closely connected with each other by family ties, as father, son, brother, etc.